Fred Lonidier shot the photographs that now comprise the University of California San Diego Visual Arts Department History Archive on a 35mm camera he carried with him day-to-day starting in the late 1960s, as he went from art student to professor. In this same period, Lonidier and his peers, Martha Rosler and Allan Sekula, who became known as the San Diego Group, would embark on the project known to their historians as “the reinvention of documentary,” an attempt to reimagine the genre in solidarity with the working class. Revisiting historical efforts, from reportage and Soviet factography to the Farm Security Administration, the San Diego Group arrived at their own strategies of generating critical distance: photographing according to fixed parameters, recontextualizing images, framing them with text. Their artworks and writings made photography and the archival form the focus of circumspection. And yet, Lonidier was there just taking pictures. Shooting what caught his eye, so to speak.

Describing his photographic activity, Lonidier explains: “It’s like I’m walking like a crab, sideways. I’m looking straight forward, thinking I want to go here, but things happen, and I end up there—there was this pull of photography on me without me being fully aware of it!”1 Prior to entering the UCSD art department, Lonidier had a formative encounter with photography’s political machinations through his involvement in the anti-war movement. Lonidier’s activism, which began while he was a sociology student at San Francisco State University in the mid-sixties, took on new stakes when he graduated and became eligible for the draft. In 1967, Lonidier joined the Peace Corps in the Philippines with his first wife, Paulette Liang, but his time there was cut short by a presidential appeal denying his draft deferral. Prior to his departure, Lonidier successfully wrote and published a letter to the editors of the Philippine Free Press and Manila Times, presenting the American interruption of his service as a disproof of the nation’s claim to be “on the side of peace.”2 The letter landed him in front of the press on his return flight home, just two and a half months later: during layovers in Manila and Hawaii, he was greeted by the United Press, the Associated Press, and Agence France, and at San Francisco International Airport, he was confronted by reporters for American television stations and ushered to a podium with “camera microphones taped to it like a mushroom cloud.”3

A Vietnam War demonstration at Seattle Civic Center, 1968. Courtesy of Fred Lonidier.

Lonidier’s first body of photographs, now the University of Washington’s “Fred Lonidier Draft Resistance-Seattle Collection,” sprang from an understanding that his future would be determined in the filing cabinets of the draft review board and before television news cameras. 4 Upon his return to the US, Lonidier got involved in anti-draft organizing, taking up photography to fire back at the cameras wielded by the police and news media. He relocated to Seattle, where his left-wing aunt and uncle offered him a place to stay. There he met Russel Wills, a fellow draft resister, and, along with Liang and Wills’s wife Cynthia Wills, formed Draft Resistance Seattle. Lonidier’s photographs from this period record the group’s actions, including demonstrations, sit-ins, and the trials of other resisters. Published in The Agitator and other underground newspapers to promote strategically planned acts of civil disobedience, these pictures constituted political action. In them, we see young activists burning draft cards and resisting arrest. They track the impulses of an activist immersed in the movement, as he and his peers repeatedly came up against the limits imposed upon them by law enforcement and the state. These photographs captured from within the struggle prefigure the dialectical maneuver he would later make in one of his early conceptual artworks, 29 Arrests (1972).

When Lonidier was in his second year of the UCSD MFA program, he attended a Vietnam War demonstration in San Diego. Having arrived with twenty-nine frames left on his roll of 35mm film, he shot the photographs that he would subsequently assemble into 29 Arrests, a grid of black and white prints. At the protest, Lonidier stationed himself behind a police photographer, who was gathering mugshots of the demonstrators during a mass arrest. His camera offers an alternate photo op, affecting a shift in perspective that positions him outside another ritual confrontation with law enforcement. As the protestors pose for Lonidier’s camera, their facial expressions range from a quiet, determined smile to a jibing laugh. These expressions are no longer mere reactions. Instead, they have become transmissions in a relay between the protestors, inscribed in a program of state control, and Lonidier’s camera, positioned just outside it. The images and their subsequent presentation amounted to a conceptual gesture that could only have grown out of a conventional photographic habit and familiarity with his surrounds. Lonidier’s critical distance was predicated on his entrenchment.

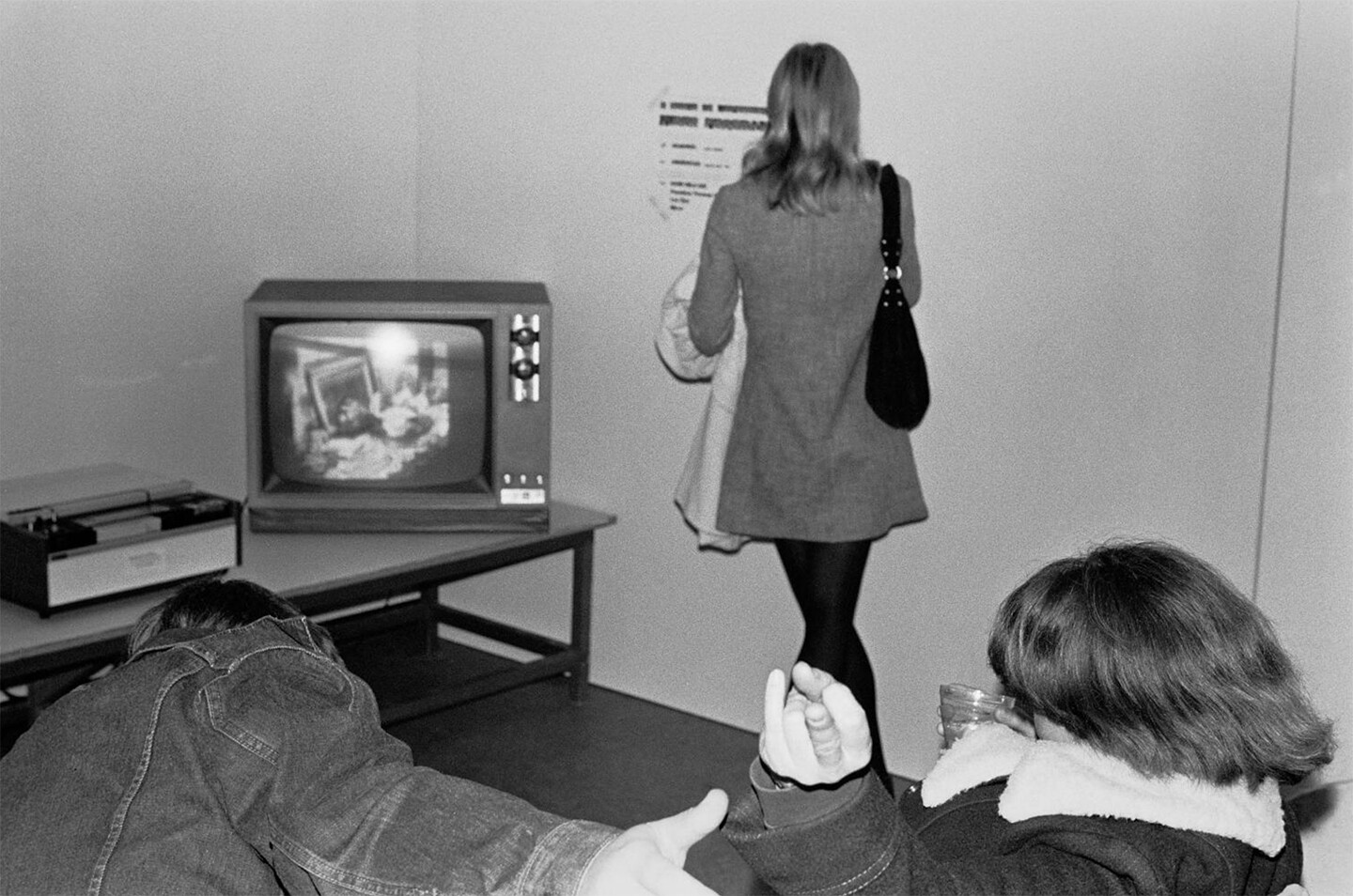

Martha Rosler (right) and an acquaintance at an opening for a group exhibition of work by MFA students, UC San Diego, 1974. Courtesy of Fred Lonidier.

When Lonidier applied to the UCSD MFA program in 1969, department chair David Antin welcomed him into the department on the basis of his straightforward, non-artistic use of the camera, which aligned with Antin’s own everyday speech poetics. Lonidier’s photographs provided his cohort an example of “regular” photography, rather than an artistic reconstruction of the medium. He put at his classmates’ disposal a concrete model, as opposed to an idealized notion (e.g., one drawn from memory). The straight photographic quality of Lonidier’s pictures also dovetailed with discourses on photorealism promoted in many painting exhibitions from 1970 onwards. In this spate of realism-focused showcases, the 1975 “Sense of Reference” exhibition at UCSD, which inaugurated the university’s Mandeville Center for the Arts, distinguished itself by showing work by Hans Haacke, Nancy Holt, and Robert Smithson alongside the usual suspects, such as Robert Cottingham and other photorealists.5 As their political ideas came into focus, conceptual artists studying at UCSD, especially Rosler and Sekula, would become increasingly focused on the mediation of political life through documentary images. Lonidier’s casual photographs of “direct” activist interventions anticipated this development by rendering these earlier modes of political art legible within the representational coordinates of documentary.

Taken from the vantage point of an excited student, outside of the parameters of an established art practice, the earliest photographs that Lonidier shot at UCSD convey the political contingency that his cohort thought was repressed in photographic art. In “Guarded Strategies,” Rosler’s April 1975 Artforum review of Lee Friedlander’s exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Rosler would show how this was supposed to be done. In one of Friedlander’s signature moves, Rosler explains, the photographer conceals his “formal” compositions by giving them the appearance of “vernacular” pictures. The incidental data of the street photograph becomes “intentional,” as if it were put there by the artist. In Sekula’s MFA thesis, “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning,” subsequently published in the January 1975 issue of Artforum, he revealed a similar sleight of hand trick performed by both Pictorialist and Social Documentary photographers. Alfred Stieglitz, eyeing the steerage platforms of the Kaiser Wilhelm II upside-down on the ground glass of his view camera, got away with “poetry.”6 Lewis Hine, standing back from the dank living quarters into which he fired, proffered “testimony.” Artistic elevation made the upper classes’ views from above appear as the heights of artistry. The institution of modern art presented the photographer always as the producer, not the produced. Lonidier’s casual photography reverses the equation. It positions him within what’s depicted—the artist as a social fact.

Visual Arts professor Newton Harrison and students making preparations for their Body Bags performance, UC San Diego, 1970. Courtesy of Fred Lonidier.

On May 26, 1970, still in the first year of his MFA, Lonidier photographed the performance Body Bags, which was staged on campus in protest of the Vietnam War. His images reveal a web of relations extending from the art department into the institutional enterprise. That month had begun with the killing of four protestors at Kent State University on May 4; not long after, governor Ronald Reagan mandated the closure of universities across California, and student-led strikes on campuses across the country prompted many other colleges to shut down. Amidst these events, UCSD professor Newton Harrison of the ecological performance duo the Harrisons encouraged his students, who were preparing to strike, to intervene as artists. Sekula, a participant in Harrison’s class, brought Lonidier over to witness the action of Body Bags. When Lonidier arrived with his camera at Harrison’s studio—one of a handful of Quonset huts at the edge of campus—the students were stuffing military uniforms with meat and putting the inanimate soldiers into body bags. From the photographs Lonidier took, one can easily distinguish between Harrison, a professor in a suit, and his students, fabricating the dead soldiers on the studio floor below him. Invited to the action by a fellow student, Lonidier’s attention is captured by a novel classroom dynamic. Taking us beyond the commemorative function of performance documentation, Lonidier’s immersion within the scene positions him to see the performance’s bureaucratic form.

Mandeville Center for the Arts, a recurring architectural setting throughout Lonidier’s archive, embodies the managerial logic of the university, linking the Visual Arts Department to UCSD’s function in a wartime chain of production. The facility’s architect, Archibald Quincy Jones, had prior experience integrating military design and artistic bohemia—from 1940 to 1942, Jones worked for Allied Engineers in San Pedro, where he was responsible for devising the layout of San Pedro’s Roosevelt Base and the Naval Reserve Air Base in Los Alamitos. Then, after serving as a lieutenant in the Navy from 1942–45, he designed the community plan and individual homes for the Mutual Housing Association of Crestwood Hills, a group of liberal-minded creative professionals who sought “a new way of life” in the Santa Monica Mountains. Describing his ambitions for that project, Jones cited a conclusion drawn by a Rand Corporation think tank, which argued that maintaining equilibrium in society demands that architects take a systems-oriented approach. His design for Mandeville featured artist studios nestled underground that opened onto a sub-level quad, surveyable from an overlook. In simulation drawings of the quad, Quincy Jones rendered artists at their easels, practicing figure drawing on the quad, and being observed from the overlook by passerby: a leisurely and bucolic spectacle to edify a student body otherwise occupied by “socially productive” work.

MFA students in the courtyard of Mandeville Center for the Arts, UC San Diego, 1982. Courtesy of Fred Lonidier.

Eleanor Antin, a performance and video artist and the wife of David Antin, thumbs her nose at these expectations in her video Representational Painting (1971), which was produced at Mandeville. One of Lonidier’s photographs of the production shows two video cameras aimed at Antin and wired to a viewing monitor, which displays a bifurcated composite of her face. In the film, Antin applies layers of makeup between smoke breaks. Her make-up “painting” is, in a word, oppositional; a retort to the passive reproductions—“representational painting”—that art students were presumed to be making there. Antin’s piece signals an artistic integration of the institutional mediation that was latent in Newton Harrison’s performance the previous year, and which became visible only in its photographic documentation. Yet Lonidier’s photographs of the Representational Painting shoot extend the representational field yet again, showing us a different social form that came about to realize Antin’s piece.

The shoot of Antin’s performance took place in an improvised television studio cobbled together from the department’s AV equipment and operated by department-affiliated participants, including David Antin, the photography professor and recent graduate Phel Steinmetz, communication student and future news cameraman Lenny Bourin, and current MFA student Louise Kirkland. One of Lonidier’s pictures of the shoot reveals a model of alternative institutional relations. Kirkwood throws a questioning look at the camera, touching her hand to her hair. David Antin proffers an open-palmed shrug. In a tête-à-tête between two frames, Eleanor and David point fingers at each other. The direction pointed by the auteur is not the only one; some arrows point beyond the program of academia. Interlocutors smoke and joke from metal folding chairs about the room. Other arrows flow around an exchange of labor. Requisite skills are sourced from the artist’s university network. Bourin, presumably in the role of technician, hovers over the controls. He holds the microphone to Steinmetz in a microphone test, miming a television interview. Steinmetz, who makes additional appearances in Lonidier’s archive as a photo technician, is assisting with AV. Lonidier’s photographs show us play taking place not only around the expectations of the institution, but in the indirect process of professionalization.

A shoot for Eleanor Antin’s work Representational Painting, UC San Diego, 1972. Courtesy of Fred Lonidier.

It is, by turn of contradiction, logical that Lonidier’s casual pictures would facilitate a survey of labor and resources. As Sekula argues in the “The Body and the Archive” (1986), the picture portrait immediately served two opposite functions: to honor and to surveil.7 The likenesses sold to the middle and upper classes, Sekula points out, could also function as evidence. They were haunted by the portraits populating police records, in the portrait cabinets of Francis Galton and Adolphe Quetelet—two nineteenth-century statistical criminologists whose independent researches founded the field of eugenics. Not directed towards any artistic “work,” Lonidier’s leisure pictures veer closer to the private and social economies at the core of institutional enterprise.

Starting as early as 1970, Lonidier and his cohort would address state and medical archives directly by restaging them. Precisely because of Lonidier’s quasi-naive neutrality, the cache of his casual pictures achieves a genuinely archival status that parries with the veracity of the police and medical archives that the San Diego Group recreated in their early works. In the late spring of 1972, Lonidier mounted his MFA thesis exhibition. For the project, he presented several of his early photo-conceptual pieces in the manner of a legal archive, lining up filing cabinets alongside their emptied contents—manila folders, newspaper clippings, typewritten indexes, handwritten notes, contact sheets, and photographs—which he pinned to the adjacent wall. Long-range shots of students and data about them were presented in a caricature of a police file. Spreads selected from porno magazines and newspapers accompanied tightly cropped photographs of bodies and gestures. Also included were the protest photographs that would later comprise 29 Arrests. The filing cabinet used in the installation was most certainly dragged out of some university closet. The manila folders, too, were presumably sourced locally. While, as Sekula argues in “The Body and the Archive,” modern art tends to repress the documentary and archival dimension of photography, Lonidier’s installation is representative of a tendency in the San Diego Group’s early works to perform the archival function overtly. Presented within the broader archive of UCSD activities, Lonidier’s documentation reveals this performance as a parallel operation—a second-order representation performed under working conditions.

Installation detail of Fred Lonidier’s Master of Fine Arts exhibition, UC San Diego, 1972. Courtesy of Fred Lonidier.

This essay has been excerpted from Nilo Goldfarb’s forthcoming book Fred Lonidier’s Casual Photography, which will be published by Nauener Platz in January 2025. e-flux Education will feature a subsequent excerpt from the publication in the early spring.

Conversation with the artist, September 3, 2021.

Conversation with the artist, September 3, 2021.

Conversation with the artist, September 3, 2021.

Fred Lonidier Draft Resistance-Seattle Collection ⟶.

“Sense of Reference: Explorations in Contemporary Realism,” March 7–16, 1975, Mandeville Art Gallery, UC San Diego.

Allan Sekula, “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning,” Artforum, January 1975, ⟶.

Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October, Winter 1986.