John Waters’s 1998 film Pecker, a raucous satire of the New York art world, follows the rise to fame of an unassuming eighteen-year-old Baltimore photographer. After a dealer from the fictional Rory Wheeler Gallery happens upon Pecker’s debut exhibition at The Sub Pit in Hampden, the young artist is thrust into Manhattan’s cultural spotlight and becomes an instant success. He sells countless prints, attends highfalutin gallery dinners, and is even offered a solo show at the Whitney. When he returns home after his Big Apple whirlwind, however, life begins to fall apart. Pecker is now recognized everywhere, his family becomes increasingly dysfunctional, and their home is burglarized. After experiencing celebrity’s unintended consequences Pecker tells the Whitney to shove it, effectively turning his back on the New York art world. When Pecker stages a redemption exhibition at his father’s neighborhood bar, curators, critics, and collectors travel by the busload from New York to Baltimore to see the show, only to be disappointed that Pecker could not be more disinterested in their presence or praise. The artist’s concern is instead redirected to the denizens of Hampden; without contrition he passes on art world posterity. The faculty, staff, and students at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) fully recognize that their audience is, by default, much of the audience that Waters satirizes. Echoing the sentiment of Waters’s film, many of those who create at MICA elect to pursue meaningful alternatives, rather than appeal to art world regimes.

Within the context of any city, art embodies a Janus-faced means. It can uplift, engage, and provoke progressive discourse, while also being a convenient path to gentrification. MICA’s MFA in Curatorial Practice (CP)—the first curatorial MFA in the United States—rigorously prepares its students to accomplish the former while being all too mindful of the latter. The program’s current director, George Ciscle, started CP in 2011 after retiring from The Contemporary, a roving contemporary art museum he founded in Baltimore in 1989, and which he popularized after co-organizing Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum project in 1992–1993. Through CP, Ciscle hoped to augment MICA’s efforts to have a “relationship outside of itself.” Ciscle blithely admits he is not training his students to become the next curator at MoMA (“not that they are not qualified to be,” he punctuated this statement). Rather, the idea of localized engagement takes precedence.

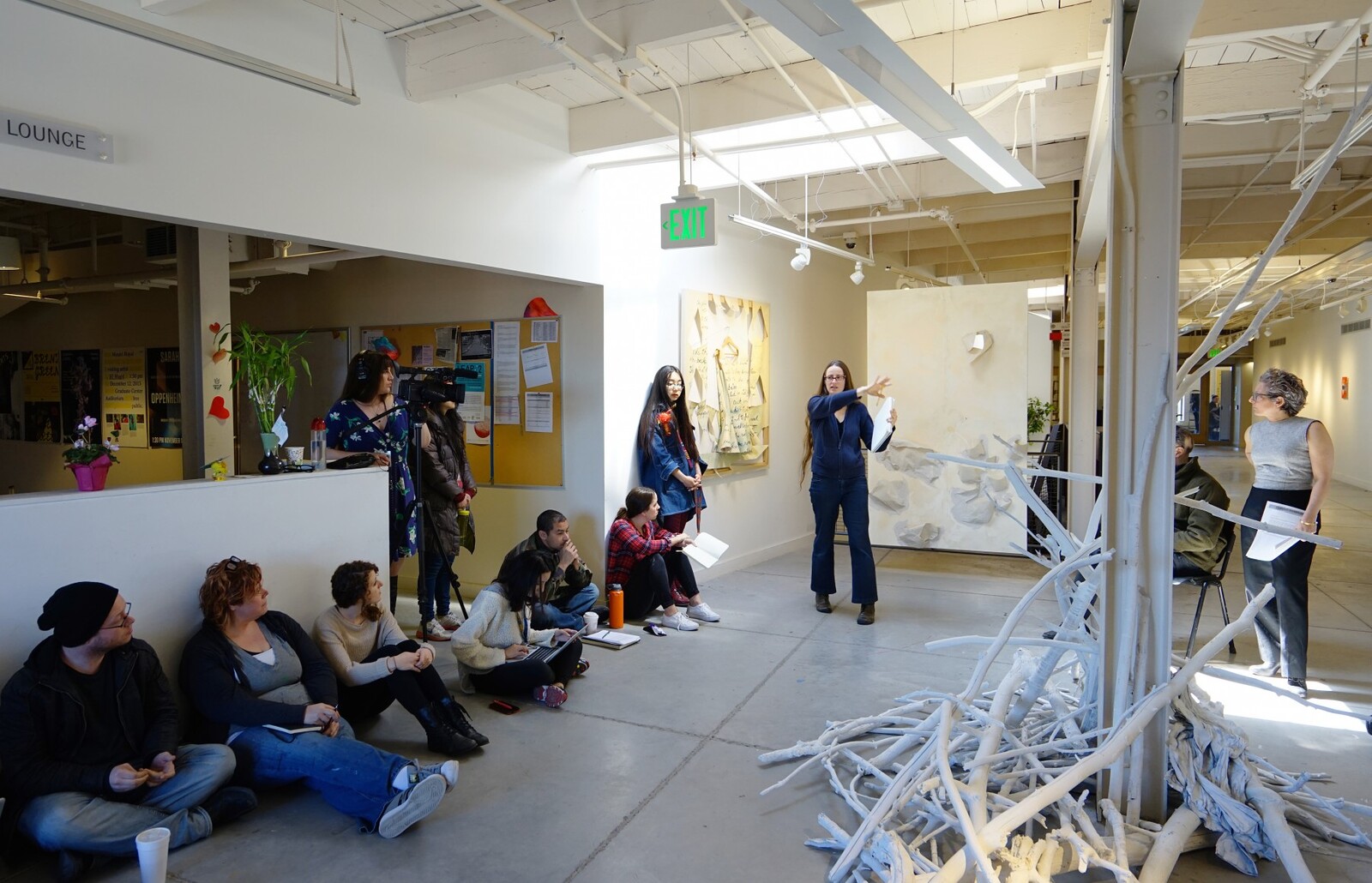

CP occupies a substantial wing on the first floor of Lazarus Center, a 120,000 square foot renovated factory and home to MICA’s graduate studios. This building is located in Station North, an arts and cultural district separated by I-83 from the rest of MICA’s sprawling Mount Royal campus. At the program’s inception Ciscle was adamant that CP be stationed there on North Avenue, outside of college campus isolation, as a “conscious attempt to seek connections with the surrounding neighborhood’s diverse population of residents, businesses, schools, and social agencies.” This location was also crucial to the program’s structure as an MFA, rather than an MA. CP’s emphasis on socially engaged and audience-minded production is what decisively distances the program from competitors. More than three-quarters of students’ credits apply to various forms of exhibition production. The rest are devoted to theory, history, and other electives. CP alumna Deana Haggag (now director of The Contemporary) recalled the importance CP placed on building relationships within the Baltimore art scene. She noted that while working “directly and intensely” with artists, community partners, and audiences, “every project, process, and product came after a very solid relationship was built with its maker and consumer.”

The politics and history of Baltimore are central to the curriculum from the outset. In their first semester students read The Baltimore Book: New Views of Local History, a people’s history of place that examines the social lives of Baltimore’s historically marginalized inhabitants during the last two centuries. After immersing themselves in Baltimore’s history and art scene (this past fall first-year students did approximately thirty studio visits with local artists), students immediately begin preparation for their thesis exhibitions that will open in their fourth semester. For thesis, students take what is essentially an ongoing class over four semesters, broken down into “Research and Fieldwork,” “Proposal,” “Production,” and “Presentation,” and taught by José Ruiz. A curator, artist, and cofounder of the Brooklyn project space Present Company, Ruiz is now primarily based in Washington DC after working several years in New York as a curator for the Bronx River Arts Center, Bronx Museum of the Arts, and Queens Museum of Art. During each seminar, Ruiz allows for as much independent work time as possible for the students to develop their individual thesis exhibitions. Thesis class usually begins with a team meeting and brainstorming session (the week I visited the class discussed how to plan for their respective exhibitions’ marketing and publication). Students then disperse to work individually as Ruiz spends one-on-one time with each student to problem solve or work through an idea.

According to Ruiz a key question in the program is, “How can you connect your artists and ideas to outside the art world?” If you just want to do an art-for-art’s-sake exhibition, that’s fine, “but you have to defend it,” says Ruiz. There have been tangible consequences to this socially conscious education model. “It’s not written or required in our curriculum,” Ruiz wrote in an e-mail, “but we continue to see that many of our alumni have become community leaders across various parts of society.” The potential for this becomes clear by looking at the diverse individual thesis projects themselves. For You Are Here, Yvonne Hardy-Phillips, a native Baltimorean and second-year student, will map the cultural history of Oliver and Johnson Square, neighborhoods in which she has been a longtime resident. Concomitantly partnering with the community and local government, Hardy-Phillips is devising an art-infused revitalization plan for her neighborhoods. Aware of the complicated relationship between art-related development and gentrification, Hardy-Phillips maintains that her goal is not to displace her fellow residents, but to “galvanize [the] community and help them see the importance of place.”

The community a student chooses to engage with can take many forms and as second-year student Ashley DeHoyos pointed out, “everyone [in the program] has different ideas of what curating can be.” Informed by year-long conversations with different Latin American groups in Baltimore, DeHoyos’s thesis project, Traces: Ni de aquí, Ni de allá, will examine the complexities of Latinidad while critiquing Eurocentric essentialism. Another second-year student, Chrissie A. Miller, will curate Bend, an exhibition that emphasizes the mutability of masculinity in a resolutely male establishment: Benders Sports Bar, a watering hole she’s frequented in Upper Fells Point where machismo is affirmed. CP alumna Melani Douglass also chose an unconventional venue for her 2015 thesis project Love on the Line, an exhibition and series of performances that took place at a Howard Street laundromat. Love on the Line transformed this locale into a de facto community center and a cathartic space after the Baltimore Uprising, filled with art by Pierre Bennu and Stephanie Safiyatou Edwards and spoken word performances by Jasmine Pope and the Baltimore Girls. “By the time of the death of Freddie Gray, the bubble had been popped,” said Douglass. “Baltimore became the epicenter of all of America’s tension and the eyes of the community were on MICA.”

As students begin to sketch out their thesis during their first year, they also take Practicum, a course co-taught by DC-based curator and critic Jeffry Cudlin and MICA exhibitions director Gerald Ross. The six students of the cohort work together to conceptualize and organize a singular exhibition as a capstone to their first year. “Practicum asks students to collaborate, and to make decisions via consensus,” Cudlin explained. “Collaboration is intense, and consensus—only proceeding after every voice has been heard, and every participant cannot necessarily agree on an issue, but can at least agree to move forward—is really, really hard.”

In the first half of the seminar students hammered out logistical concerns for their Practicum exhibition Fathers, Brothers, Sons, a humanistic project speaking to the spectrum of experiences that African-American males in Baltimore may identify with. Elaborating on the rationale behind the theme, first-year student Sheena Morrison expressed that for many African-American men, “race and masculinity are inseparable.” Healthy debate ensued when first-year student Carol Dyson asked her colleagues about the cohort’s group essay. Morrison suggested to her classmates that it could function as the collective “gesture” of a unified cohort. First-year Fitsum Tefera contended that it should be more of a collectively written “analytic reflection.” Ross chimed in, supporting Morrison’s idea of a collective gesture and reminding students that the exhibition “isn’t just an argument about masculinity … it’s also an argument about what a show can be.”

The Practicum class essentially organized itself into a fully operational art institution, dividing into Graphic Design, Education, Exhibition Design, Research, PR, Budget (Finance), and Project Management teams, which would work independently over the week and share progress during the subsequent seminar. After discussing the graphic design package for the exhibition’s brochures, posters, and postcards, the class planned time to focus on the theoretical underpinnings of the exhibition. First-year student Liz Faust led a discussion of an excerpt from Privilege, Power, and Difference by Allan G. Johnson. Faust was careful to consider how the reading related specifically to their exhibition, advising her classmates that privilege “is not what you are,” rather, it is “what is applied to you.” Remarking on the discussion’s relevance to Fathers, Brothers, Sons, Faust drove home that when “you’re talking about masculinity … you’re also talking about male privilege.”

A few floors above CP is MICA’s Mount Royal School of Art (Mount Royal), which offers a multidisciplinary MFA. The multidisciplinary framework, according to the program’s website, exists to help students “work in ways most appropriate to their individual research—focusing their exploration within a specific medium or crossing into a wide array of disciplines and media as they engage in intensive studio practice.” Despite “multi-,” “trans-,” and “interdisciplinary” being contemporary buzzwords, Mount Royal was founded in 1974 and is currently directed by Luca Buvoli, the program’s only tenured full-time faculty member. Although Buvoli is the program’s sole advisor for twenty-six students, his commitment to helping younger artists grow compensates for this. “He’s very attentive,” first-year student Maren Henson told me, and “always five steps ahead of you.” She was astounded by “what he can see in you, without knowing you personally for very long.” Francisca Carvalho, a second-year student, noted that Buvoli has a knack for selecting “people not only because of work, but because of personal qualities.”

Buvoli invites many visiting artists, like Omer Fast and Suzanne Anker, to come once a semester, and artists-in-residence, like Katrín Sigurdardóttir, Dario Robleto, and Stephanie Barber, to visit multiple times a year or semester. This continually introduces new perspectives and voices into the department’s conversation. At the beginning of March, Cuban performance and installation artist Tania Bruguera joined Buvoli as an artist-in-residence. Prior to an incisive and fast-paced critique, Bruguera asked students, “What degree of honesty do you want from me today?” Nervous laughter followed an uneasy silence. Nine students presented their art over three hours. The students critiqued the work amongst themselves for approximately twenty minutes. Bruguera and Buvoli would then follow up for about ten minutes more. The first to go was Edward Sanchez, who presented dozens of small headstone-like sculptures made of concrete and brightly colored detritus, arranged in a grid. His classmates were generally supportive, providing associative clues to help him figure out where the work was headed. Danni Tsuboi chimed in, suggesting that the sculptures evoked “a memorial somewhere between a cemetery and an archive.” Carvalho proposed that the piece revealed a “process of digestion” with a sense of materiality that reflects Baltimore and Puerto Rico, from where Sanchez hails. A volley of concise and diverse insights, Buvoli’s comments nimbly moved across conceptual, formal, materialistic, and cultural dimensions. Bruguera was blunter. “I don’t feel like it’s a working piece and I’ll tell you why,” she offered candidly. Bruguera suggested there was an unresolved relationship between the arbitrary and the intentional in Sanchez’s work, in which the aesthetic of de-skilling occurred as an accident. Such formal outcomes, she asserted, “should be a more conscious decision.”

The subsequent critiques showcased the breadth of production in the Mount Royal program. Our group of twenty-nine people packed into Amber Eve Anderson’s sunlit studio and tried on a virtual-reality headset, which presented off-kilter visions of the space in which we stood. Mary Baum showed a video installation in a storage room; galactic yet disco-like imagery was projected on a fabric shroud. Josh Sender unveiled two websites: exhibitionspac.es and itwasallveryimpressive.com. While the latter clearly read as a net art project, exhibitionspac.es was more of a resource, helping artists fabricate documentation of their work by providing Photoshop tutorials and an image database of thousands of empty white cubes. At once a public service and cheeky comment on today’s overemphasis on image circulation, exhibitionspac.es actually provoked a question I had not bothered to think of for some time: Is this art?

Bruguera’s time at Mount Royal concluded with a seminar in which the students analyzed her idea of Arte Útil, or “useful art.” As preparatory homework, the twenty-six students went through the Arte Útil online archive and preselected Arte Útil case studies to discuss. One project discussed was (P)LOT (2004), initiated by Michael Rakowitz in Austria, which proposed renting unused plots of land, such as parking spaces, for “alternative purposes,” enabling locals to “establish temporary encampments or use the leased ground for temporary gardens, outdoor dining, game playing, etc.” After discussing several of these socially engaged projects, which thoughtfully catered to the diverse interests of the Mount Royal students, Bruguera asked the students, in a moment of openness and egalitarianism, “What didn’t you like about Arte Útil?” Carvalhno voiced concern about authorship, describing it as “problematic.” Bruguera agreed that authorship as a conceit is indeed problematic, so it’s “something we [Arte Útil] try to avoid.” Carvalhno’s point was that Arte Útil’s version of authorship is “actually the same thing” as in other forms of art. After Bruguera and Carvalhno attempted to reconcile their disparate points of view, Bruguera encouraged the students to do the following at the seminar’s close: “propose different functions for art in society”; be aware “that we are under a regime of the art world,” and “always question what art is for.”

To use Bruguera’s Foulcauldian terminology, the MFA is of course, a “regime of the art world.” While there are the promises of artistic growth and network formation, the MFA is still a thing of hierarchy and power that can oppress those who enter it, especially financially. (While almost all students I spoke with were satisfied with their MICA education, the majority were paying more than $40,000 in tuition per year.) The increased professionalization of the art world during the latter half of the twentieth-century confected the need for an MFA. Now many art schools are faced with a double bind: decreased undergraduate enrollment and increased austerity measures. One consequence of this is a proliferation of low-residency MFA programs that allow the maximization of existing resources to increase revenue. Moreover, after Web 2.0 the idea of the low-residency MFA somehow seems more plausible and logical, especially during an era of unprecedented image circulation, MOOCs (Massive Open Online Course), and post-Fordist flexibility. To offset declining revenue, one MICA faculty member indicated that, as of three or four years ago, the institution developed the goal of creating seventeen new graduate programs. (This calls to mind Tristan Garcia’s words: “Our time is perhaps the time of an epidemic of things.”) While one might assume that MICA’s MFA in Studio Arts (MFAST), as a low-residency MFA, is a product of twenty-first century conditions, it was actually founded in 1990 as the first low-residency MFA in the country. Created to satisfy a new market, the program was, according to its founder Karen Carroll, the first program “explicitly calendared” around the schedules of teachers who increasingly needed graduate degrees to continue teaching.

Like most low-residency programs, MFAST allows its students to “maintain [their] lives,” says program director Zlata Baum. The MFA takes about three years to complete (tuition ends up being roughly equivalent to MICA’s two-year MFAs), with four required six-week summers in residence at MICA. This is supplemented by an intensive four-day winter critique session and independent research and creation during the fall and spring. Alumnus Billy Friebele described the format as “actually helpful … because I became more self-reliant.” Four years allowed him “to go through multiple transformations that would have been impossible” otherwise. Recent graduate Joy Moore corroborated Friebele, who enjoyed the ability “to ask yourself questions that there might not be time to answer meaningfully in a two-year program.”

One of the most popular sources of theoretical discourse in the MFAST program (and throughout MICA, for that matter) is faculty member John Penny, a theoretician and sculptor. With a dry sense of British humor, Penny is quick to share his skepticism of postmodern art (a “confection” of the New York art world) and fluency in Marxism (he was reading Postcapitalism by Paul Mason when we met). The summer’s many critiques, visiting artist talks, and technical workshops are augmented by Penny’s lecture series, which runs the gamut of topics, from the Altermodern to Russian Formalism and Romanticism. The goal of this theory-imbued curriculum is “to help students become more articulate about their production, understood as production,” says Penny, adding that it is “not geared toward the commercial market,” but rather the fruits of “self-directed labor.” Consequently, Moore says, the program “depends upon your needs, experience, and the magnitude of your projects.” Because of this, the program makes sure “there is always someone to talk to or turn to for advice, connections to artists and alumni, and resources for research materials.”

The recent bloom of low-residency MFAs across the United States may be an aftereffect of a larger economic impasse within art education. This, of course, does not mean an artist might have a less meaningful graduate school experience in a low-residency program than another kind of MFA. Nevertheless, as the regimes of the art world expand and increasingly demand more from individuals in order to qualify as participants, there is greater reason to seek out alternatives. The people who comprise MICA, a key intellectual hive and link between communities in Baltimore, work to create these alternatives from both within the system of higher education and the city itself.

—Owen Duffy