https://smfa.tufts.edu/

Facebook / Twitter / Instagram

I. Principles, Politics, and the Past

As I navigate from Cambridge, over the Charles River to Boston, I am struck by the simultaneous sterility and coziness of my home city. Red brick abounds, hospitals loom everywhere, and a museum known for its extensive classical collection but accused of “small-city provincialism” sits at its heart.1 When finding parking, you realize you could wind up in a medical supply bay just as easily as you could in the Museum of Fine Arts lot. We are in a land of massive institutions of all stripes. Adjacent to the museum pillars, gargantuan bronze baby heads by artist Antonio Lopez Garcia guard the School of the Museum of Fine Arts (SMFA) entryway, which feels in but not of the museum itself. The thinking, art-making, and exploration happening here can be called anything but narrow-minded.

Founded in 1876, the SMFA was originally known as the “School of Drawing and Painting”—an antiquated title that sits in contrast to a school (its master’s program in particular) that prides itself on its interdisciplinarity. In 1927, architect Guy Lowell built the main school building at 230 Fenway, right next door the Museum of Fine Arts. Spacious and old-school, it’s reminiscent of the alternative middle school I attended across the river in Cambridge. The homey aesthetics of the facility appear to be in line with one student’s response to why she chose the MFA program at SMFA: “It felt like a family.”

Yes, the building certainly feels “lived in”: handwritten names of students line the walls in the woodworking and welding shops to mark when they’ve been certified in safety protocol; the print studio features a well-loved if slightly precarious printmaking machine (a student tells me you need to maneuver delicately or it sticks); and the aptly named Cafe Des Artes, which was started by an alum, serves homemade entrees, sandwiches, and baked goods daily. It should be noted, however, that for all this lived-in-ness, the school still boasts some impressive facilities. The Advanced Production Lab features a state-of-the-art laser cutter that makes two-dimensional prints. The graduate video lab houses the newest Macs. Among the equipment rentals, students can take out Black Magic video cameras and projectors for their personal use whenever they want.

With the appointment of architect and designer William A. Bagnall as dean of the SMFA in 1968 (eight years after the master’s program started), faculty hierarchies were eliminated, all students were given access to all courses, and a review board system was devised. For the past twenty-three years, the Graduate Steering Committee has governed the SMFA’s MFA Program. This governance committee is made up of six (out of twenty) graduate advisors and two MFA candidates, and its membership rotates. For three decades there was no director of the MFA program; instead, leadership was a collective effort of the Graduate Steering Committee, and curriculum revisions were made during annual retreats. In 2000, however, the Graduate Steering Committee retreat formulated the basis of the MFA’s current program, which features a single academic director.

Over the course of the history of the SMFA, many notable alums have passed through the doors of 230 Fenway (and subsequently the doors of the graduate building over in Mission Hill). Ellsworth Kelly is among them. His piece Blue Green Yellow Orange Red (1968) hangs in the Linde Family Wing—the contemporary gallery at the MFA. The museum also features the work of SMFA graduates Nan Goldin and Doug and Mike Starn. (Sadly, alums Cy Twombly and David Lynch are not featured, but their time there is frequently noted.) Strolling through the large stately museum next door and seeing the work of artists who have a shared educational experience must inspire hope for many artists in the program; you could arguably spend the duration of your two-year degree getting lost inside the museum. Of course, a rigorous course of study still has to be attended to, and the MFA program at SMFA has fine-tuned its own tenets over the years. Mary Ellen Strom, the current director and a video artist who regularly shows her work in New York, Boston, and abroad, identified the major principles of graduate education as interdisciplinarity and mentorship.

Interdisciplinarity in particular has been a foundational principle of the program since its inception in the 1960s. Students in the graduate program do not declare a major but are encouraged to experiment across artistic disciplines. This concept and practice extends beyond artistic mediums to include other disciplines as well. Consequently, the program produces artists who work not only in “fine art” but also as curators, businesspeople, and educators. The concept of the artist as a creative entrepreneur is a working reality here.2

When the program was founded, “interdisciplinary” referred mainly to the intersections between painting, drawing, film, and so forth. As the meaning of that word shifts rapidly, today the institution keeps up. “We are asking what interdisciplinarity looks like in the twenty-first century as opposed to the twentieth century,” explains professor María Magdalena Campos-Pons. Among these current concerns, Campos-Pons identifies the proximity of art to social engagement, the horizontality of the digital world, and the design of relationships as opposed to space and objects as key to a twenty-first century understanding—all of which, she asserts, the SMFA is particularly equipped to take on. While such global concepts could overwhelm even the most committed artist and thinker, fortunately SMFA students don’t navigate these emerging disciplines and questions alone. Enter the second pillar of the MFA program: mentorship.

As I walked through the partitioned studios at the Mission Hill building with Mary Ellen Strom, she made evident the criticality and care that she and her colleagues invest in their students. Strom knows the name of every student she sees and the ideas they’re working with. (In some cases she has even met their families.) Her feedback, along with that of her colleagues, does not pull punches but remains rooted in a genuine belief in the individual vision of each student.

Strom explained to me that second- (and final) year students participate in three critiques each semester to work towards a culminating group exhibition at the Cyclorama—an enormous historical building in Boston’s South End with an oculus the size of a boat. Present at these critiques are advisors that come from outside the program—curators or scholars who have not seen the student’s entire evolution but who encounter them as they are honing their vision in the second year. Somebody like Edward Saywell, for instance, a curator of modern and contemporary art at the Museum of Fine Art, might be one of these outside advisors present at your final-year critique. (Yet another way in which the museum looms large in the consciousness of these students.)

I sat down to speak with Professor Barbara Gallucci, who has been working at SMFA for fifteen years. Gallucci described to me her role in mentoring students:

As teachers we help them figure out what they want to talk about first—it’s a different way of teaching. It’s much harder. It makes you more courageous in your own work. We have to make sure they don’t lose track of that scope. Our program asks what you care about. You can be a video artist and a sculptor, but we focus on the development of thinking and research. Whatever you need to do to execute that idea in the best way is where the importance of process comes in.

In a maelstrom of disciplinary options, clarity of thought and vision remains central to this course of study, and the mentorship provided is crucial to see it through. With this kind of training in critical inquiry and academic mentorship, it follows that many alums go on to teach. Later, when reflecting on my meetings with both Gallucci and Strom, I kept thinking of an Ellsworth Kelly quote: “Making art has first of all to do with honesty.”3

One might ask if starting with the conceptual distracts from developing “skills,” a question that certainly depends on what you consider a skill these days. One could either critique graduates for not emerging with a more classical training in painting, or laud them for having a working knowledge of welding, video editing, and independent curation. From my observation, most students seem equally adept at executing a composition as they do at articulating a conceptual lineage for what they’re working on.

Also in line with the MFA’s emphasis on interdisciplinary, Strom explained that the program encourages its students to think of Boston as “one big institution” that they can take advantage of. Tufts University accredits the MFA program and students take four courses there—two art history courses and two electives. Many students end up taking classes in disciplines such as biology, cultural anthropology, or history that relate to their particular artistic interests. They can also sign up for classes at Northeastern, or cross-register at MIT. During their first semester students take the Contemporary Art Seminar, the only mandatory course in the program. The class spends three weeks each on the global landscape of the art exhibition, the relationship between the viewer and the artist, conceptual design, and contemporary objecthood. A different faculty member covers each topic, and these instructors vary from year to year. Once students have completed that course, the institution is their oyster. The pragmatics and politics of the SMFA’s educational values play out most clearly in the classroom and individual critique.

II. Critiques, Classes, and “the Future”

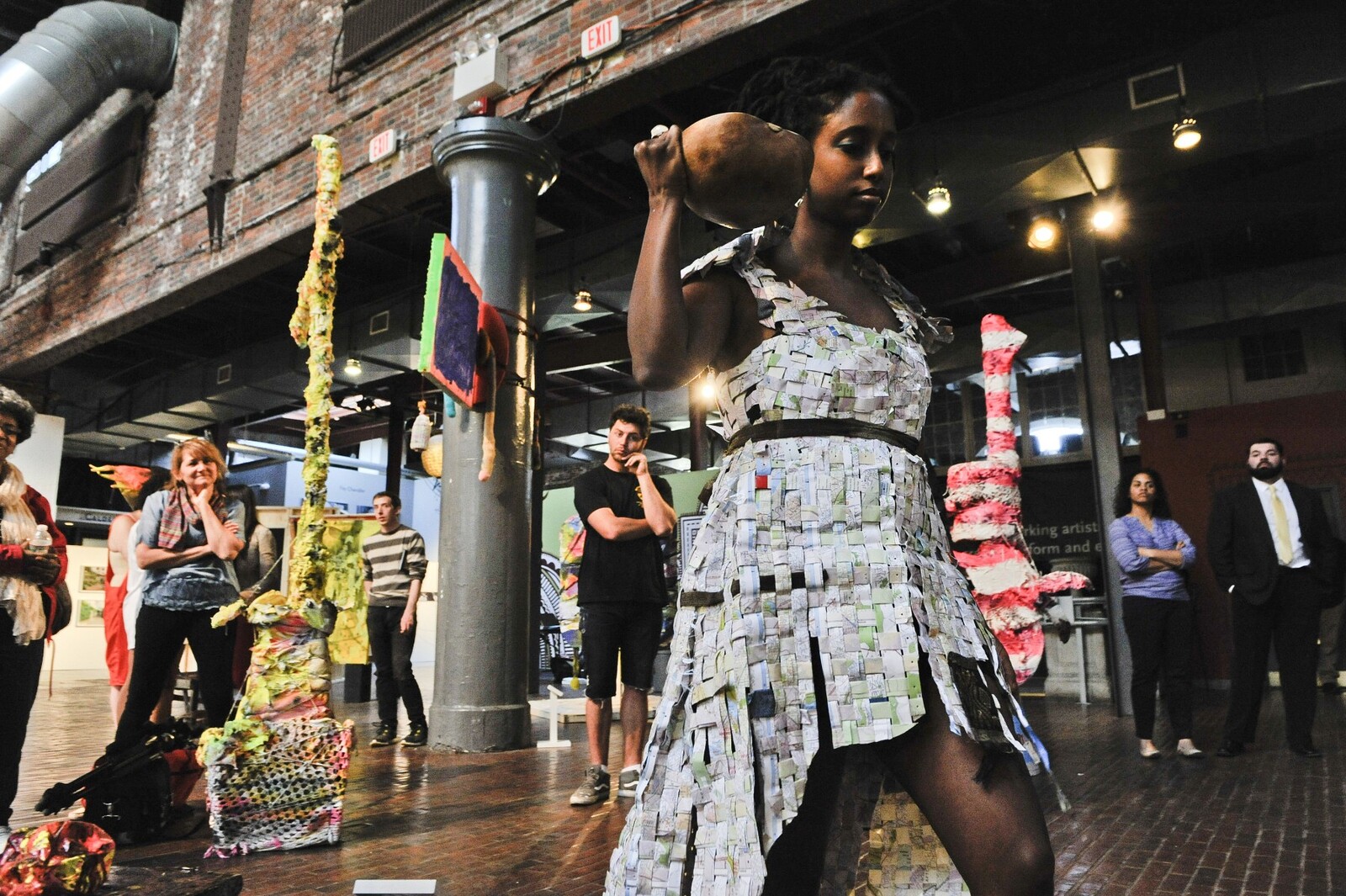

On my first morning at SMFA, I attended Danielle Abrams’s Graduate Performance Projects class. A student presented a thought experiment in intentionality and subjectivity, which yielded a subtle and cerebral discussion about the impossibility of signification in art. The critiques from students and faculty were generous yet incisive. As we observed a rudimentary wire sculpture on a pedestal in the center of the room and began to discuss it, a robot voice interrupted: “BE OBJECTIVE. B-E OBJECTIVE.” Uneasy laughter and mild discomfort filled the room. Professor Abrams, observing that the piece wasn’t fully realized, encouragingly opined: “The awkwardness is great. It’s okay to sit in it.”

Later I visited Mary Ellen Strom’s graduate video class where first-year students presented three-channel video projects made in imagined collaboration with an established video artist of their choosing. Strom imparted a great deal of technical knowledge to her students with the help of Steven St. Francis Decky, a fellow faculty member. Strom connected with one student in particular by framing his work around the performance of gender. As the student was seemingly unfamiliar with gender studies and the like, Strom appropriately suggested that he read Judith Butler and a few other theorists. Then, realizing the resource of her classroom, she took a step back to consult the other students—one from Saudi Arabia, two from Tehran, two from China, and one from Lebanon—about how the piece might be received in their respective cultures. A moment of pedagogy was transformed into global feminism in praxis. You could see the students trying to establish a common language—and this occurred throughout the class, whether the discussion was about mounting a video projector or the subtleties of cultural theory.

Individual critiques filled the afternoon, and this was where the program’s attention to mentorship was most clearly manifested. Most of the critiques I observed were in the company of Strom, who began every student interaction with genuine interest and ended every critique with a handshake. She appeared to be equal parts astute cultural thinker, den mother, and accomplished practicing artist. Code-switching seamlessly between these modes, Strom offered varied feedback that operated on both practical and theoretical levels.

We visited the studio of first-year student Laine Rettmer, who worked as an opera director but returned to graduate school to study visual art. Rettmer showed us two videos. In the first a woman suspends herself from a basketball hoop while another crashes through desks lined up perfectly in a cavernous MIT test-taking hall (which I thought was reminiscent of Pina Bausch’s Café Mueller). The aesthetics of both videos were strikingly cohesive, but even so, Strom pushed Rettmer to go further: “Think about institutional disruptions, think about it in Boston, which is full of institutions. Note the interrupted action in the first video—that was a success point. Something you may want to repeat.” In response to a shot with a slightly awkward framing in Rettmer’s other video, Strom said, “There’s a wonderful action that you’re doing but we’re not seeing it. It will be worth shooting again. You’ll learn something!”

We proceeded to the studio of second-year student John McCool. Blending his background in archaeology with his drawing and mapping practice, McCool was tracing the origins of a Native American artifact he found at the Museum of Fine Arts by constructing a “murder map,” complete with real and false leads. He presented a sketch of a potential infographic that measured the moral fortitude of collectors who had trading relationships with Native Americans. Images of artifacts they traded hung on the wall next to the murder map. A well-constructed experiment in information mapping, there was an elegant simplicity to the manner in which the piece contemporized archaeology. Strom suggested that McCool apply to the Fulbright Border Program and offered to write a recommendation.

Strong conceptual and pragmatic feedback was present in all the critiques I witnessed by Strom, Abrams, and Gallucci. Whatever former training each student brought to the program, when it came to rigor in thought and form, the standards were high and feedback was generous. Of course, with a price tag of $42,404, it’s important to know, or at least have options for, what you’ll do after the program ends. It seems as though many of the second-year students are well-prepared for the next steps. In keeping with the familial ethos of the program, many students return after graduation to take teaching positions. One of the advantages of staying in Boston after graduating seems to be the numbers; as Strom says, “There are so many schools here, so there are about twenty adjunct positions available in Boston—the odds are better here [than in New York].” Graduates also return directly to SMFA as adjunct faculty. The number of alums in teaching positions speaks highly of the school’s respect for its graduates and its career support for them.

Other students have stuck around the school in more novel ways. Second-year student Tamara Al-Mashouk, a video artist who hails from Saudi Arabia by way of NYC, organized an outdoor fine art gallery at Fractalfest, a grassroots festival involving around eight-hundred people founded by Fractaltribe eight years ago. This past year, Al-Mashouk explained, “They gave me a forest and I brought in fine art.” She’s also participating in a group show at 555 gallery on Newbury Street in Boston’s busy shopping district. Furen Dai, another second-year student, is working with faculty to launch an SMFA exchange program in China as she completes her final semester.

Given that interdisciplinarity is in many ways a presupposition in the art and working worlds, the MFA program at SMFA finds itself in a privileged position. The school offers the resources—and perhaps equally importantly, the guidance—for self-directed artists to experiment. When I asked Furen Dai to describe the ideal SMFA master’s student, she told me they had to be “open-minded.” I would add that the student should also be as willing to focus as they are to explore. The program is a playground for intellectual and formal ideas, but one that asks students to take their work seriously in the real world—no matter what discipline they find themselves in.

—Katherine Cooper