https://arts.vcu.edu

Facebook / Twitter / Instagram

“I’m broke as fuck and have been homeless for four months.” Tinged with desperation and saturated with reality, this is how Clifford Owens prefaced his recent artist’s lecture cum performance at Virginia Commonwealth University’s School of the Arts (VCUarts). Visiting faculty in the Sculpture + Extended Media department, Owens would seem to embody post-MFA success: a graduate of the Whitney Independent Study Program, a steady track record of important museum shows, and a much publicized and controversial solo performance at MoMA PS1. While some who know Owens’s work might dismiss his blunt words as hyperbole, or at the very least suggest we take them with a grain of salt, they are imbued with empathy and resonance, particularly for the ears of those about to graduate from a program like VCUarts. More often than not, artists will finish graduate school and find themselves in situations that come close to the one Owens describes: underemployed, a burden of financial debt, with the added pressure to move to and show in New York. Such are the realities that face newly minted MFAs who wish to enter the equally spectral and bandied “global art world,” a shape-shifting and imagined universality. If these symptoms indeed speak to our contemporary condition, how does an MFA program prepare an artist for this alluring yet much-maligned global art world? Can an MFA program even adequately do so?

Before wrestling with these larger issues, I want to mention some practical aspects of life at VCUarts. There are five “fine arts” departments that offer an MFA: Craft/Material Studies, Kinetic Imaging, Painting + Printmaking, Photography & Film, and Sculpture + Extended Media. Many of these departments have existed in some form or another since VCU was officially established in the 1960s, but have rebranded themselves since the new millennium in order to accommodate the expanded field. Each department’s graduate studios are clustered together in different areas of the expansive Fine Arts Building, colloquially referred to as the FAB, with the exception of Photography & Film’s, which reside just down the street in the Pollak Building. Richmond itself is a dichotomous small town. Within this southern city, equestrian statues of confederate generals coexist alongside a progressive and creative community, of which VCUarts is a key component. It does not take long before new residents start running into colleagues and classmates at Lamplighter or Ipanema—Richmond’s equivalent to Greenwich Village’s old Cedar Tavern. While some might consider Richmond peripheral to the major art cities, there are tangible benefits to attending art school here. Life is affordable by today’s standards—$250/month rent is entirely possible. It is close enough to New York (six hours by bus) that students and faculty alike can remain connected to the larger conversations that course through the art world there. In fact, many graduate students find themselves in New York once, twice, or more during a semester, either through their own volition or as part of a faculty-led trip. Crucially, VCUarts is far enough removed from the hustle that its own distinct discourses percolate and thrive. The accessible size of both the city and program contribute to an overarching sense of creative community, which is sure to be enriched pending the 2017 opening of the university’s soon-to-be-built Institute for Contemporary Art. There is much happening at VCUarts, but I will focus on the two departments with which I have the strongest connections (as an art history PhD candidate there), built through countless studio visits, trips to New York, and long conversations over the years: Painting + Printmaking, and Sculpture + Extended Media.

VCUarts implements a dialectical approach to studio and professional practice: rigorous studio work plus a healthy awareness of the art world’s apparatuses are key to a sustainable career. Chair of Painting + Printmaking Arnold Kemp’s “Professional Practices for Artists” seminar ensures that students are advised of the interconnected economies, institutions, people, and discourses that construct the imagined universality in which members of the global art world participate. Kemp encourages students to think globally in multiple senses of the word. Attempting to envision the bigger picture from the outset, students write and present their own obituaries at the beginning of the semester, thus defining what success means to them individually. In a weekly exercise, two students present on different outposts of the art world that could be alternatives to New York. From Leipzig to Tokyo, Kemp’s students weigh each locale’s merits and challenges, and analyze everything from gallery scenes to visa requirements. In one class, second-year painting students Devin Harclerode and Kristin Sanders shared an overview of Los Angeles. Along with detailed handouts, their presentation included interviews with LA artists about life on the West Coast, comparative analyses of the real estate market in relationship to Richmond’s, and an extensive list of artist-run spaces. Then ensued a theoretical and practical discussion based on Thierry De Duve’s essay “The Glocal and the Singuniversal: Reflections on Art and Culture in the Global World” and Pamela Lee’s “Boundary Issues: The Art World under the Sign of Globalism.” While Kemp motivated the students to answer questions that might incite debate among art historians, critical theorists, and art professionals (e.g., What allows biennials and art fairs to proliferate? What does it mean to be an itinerant artist?), he also offered straightforward advice about art-world decorum, such as how to engage gallerists at fairs. Class concluded with a pop quiz. Each student had thirty seconds to give an elevator pitch about their work, allotted only a few seconds to hastily gather thoughts. After the pitches, Kemp stressed the ability to have multiple concise statements about one’s work that appeal to “different registers.” In other words, artists must be able to communicate their core concerns to people with different levels of expertise—the collector, the fellow artist, as well as the curious parent. In order to connect with others and build the necessary relationships to realize their different definitions of success, one must be flexible, adaptable, and accessible. Within the parameters of the seminar, students do not simply speculate about the global art world and how to navigate it; they actively participate in it. From October 12–17, Kemp led his entire professional practices seminar on a six-day trip to Mexico City to visit galleries, artists, curators, and collections, all on the VCUarts dime. Students thus had the opportunity to witness themselves—summoning Pamela Lee’s words in Forgetting the Art World—as both “objects and agents” of globalization. “[The] class is about exposing us to a variety of ways to start a career after grad school, and supplying us with crucial information about the workings of the global art world,” notes painter Mat Gasparek, adding, “The trip to Mexico is part of this focus.” Painter Saulat Ajmal, in an email sent during the class’s trip to Mexico City, said “If we weren’t coming here as a class I doubt I would consider Mexico City [as a career starting point.]” Being on the ground, however, Ajmal discovered a city “full of potential … affordable and accepting of foreigners.”

While a seminar like Kemp’s is wholly necessary as art’s workers and institutions become increasingly professionalized, the studio remains an equal concern to the VCUarts MFA program. Sculpture + Extended Media Chair Matt King characterized the studio for his students as the place “where inventive research is coupled with rigorous criticality.” Collectively speaking, King views it as “an aspirational space, where artists test the limits of form and cross the threshold of meaning into new knowledge, new sensations, and new experiences.” Clifford Owens devoted an entire three-hour seminar to discussing the ontology of the studio for first- and second-year sculpture students. His charismatic demeanor and discursive-based practice naturally translated to the classroom setting. Assuming the role of interlocutor, Owens would recite a particularly rich passage from Daniel Buren’s “The Function of the Studio” and quip, “Damn that’s good. What do you think?” Discussion revolved around tearing down the studio as a construct and exposing the possibilities of working beyond the conditions provided by a physical space demarcated by four walls. “Being flexible is a given at this point,” remarked sculpture student Savannah Knoop. Another student, Pallavi Sen, postulated that “the studio legitimizes the artist,” after recalling a time when she worked out of her bedroom. Agreeing with Sen, Shana Hoehn then criticized the widely held idea that “you’re not taken seriously if you don’t have a studio.” Driving the conversation forward from this point, Owens asked, “Why are we so obsessed with the spatialization of creativity?” Collectively, the class seemed to agree that the studio can actually be reframed and redefined as something siteless, more akin to a state of mind. Nevertheless, the studio has greater implications than being merely a site of production; it has become something with cultural cache that can even be potentially “oppressive,” or can impose limitations on an artist’s productive potential, as sculpture student J. Avery Theodore Daisey Collins explained. For their next meeting, Owens gave the students a two-part assignment: read Kathy O’Dell’s book Contract with the Skin: Performance Art, Masochism, and the 1970s and, in their studios, perform an exegesis of this tome. Fully equipped with an awareness of the permeability of their discipline’s keystones, students were then encouraged to break out from them.

Coursework at VCUarts shapes intellectual thought while imparting a sense of access. MFA students gain access to the experiences, ideas, and people necessary for a fruitful studio practice and career. They are encouraged to supplement their studies by taking electives outside of their department’s curriculum. Many enroll in art history and theory courses, such as Colin Lang’s “The Noise in the Arts,” Sarah Cunningham’s aesthetics class, and Robert Hobbs’s travel seminar. As a former TA for Hobbs’s travel course (he is my dissertation advisor), I have attended three of these trips and the demographic is always a healthy mix of art history students and MFAs. Students meet their required forty-five course hours by traveling up and down the East Coast for a seven-day trip over spring break. The topics of Hobbs’s travel classes have rotated over the years, from Robert Smithson to Marcel Duchamp to the Hudson River School. Class is held at museums, galleries, collectors’ homes, and other locations. Itineraries vary depending on the course’s subject, and such an endeavor inevitably comes with a degree of spontaneity and improvisation. During the spring 2013 seminar, former Painting + Printmaking student Thomas Burkett noted the apropos irony of the class discussing Smithson’s writing at a Burger King in Passaic, New Jersey; Burkett described the “updated corporate monument” as a fitting locale for a seminar on Smithson, whose series of well-known snapshots “Monuments of Passaic” dubbed the city’s banal features (drainage pipes, a bridge, a sandbox) quotidian monuments.

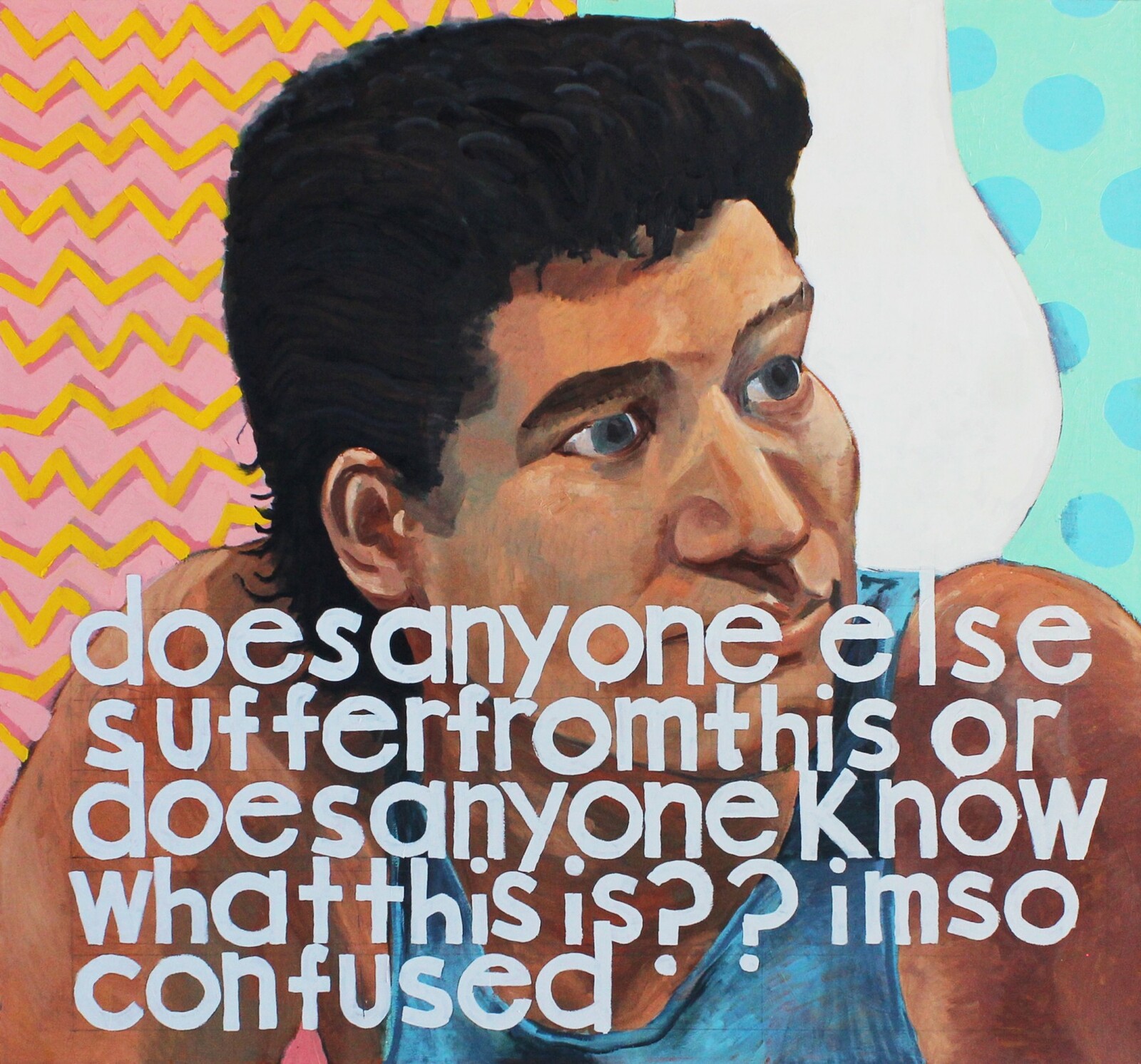

Still, extensive coursework alone cannot prepare an artist for the global art world. Artwork must be produced and discourse must be generated. The Painting + Printmaking critique led by Holly Morrison and Cara Benedetto evenly divided three hours between the art of three students: Gasparek, Wesley Chavis, and Jake Reller. Morrison prompted the analysis of Gasparek’s text and image paintings with a straightforward question: “What do you perceive and why?” The conversation around Gasparek’s works, which conflate angsty train-of-thought statements and portraits of Nineties-era television stars, focused on how the formal decisions best conveyed and related to the artist’s core concerns. Does the “brutality” of these paintings (to use student Eric Diehl’s term) show process, or speak to something else? How does the work’s typography relate to the text’s hurried and anxious feel? Painting student Kristen Sanders made a comment about the crit itself, observing that since “the person whose work is being critiqued does not introduce the work … usually whoever speaks first, or the first several comments, sets a tone that others end up following for the rest of the crit.” Benedetto eventually steered the conversation back toward the painting’s subject matter and sources, pointing out the paintings’ emphasis on Eighties/Nineties ideals of masculinity, and how these images have looped back into the contemporary moment. Towards the end of Gasparek’s critique, Morrison asked the artist to consider what is “essential to communicating what you’re trying to get across in the work” moving forward. Gasparek, Chavis, and Reller spoke little and listened intently, absorbing their peers’ feedback so that they might answer some of the larger questions, such as the one posed by Morrison, at a later date in the studio. At the end of the last critique, Morrison closed the evening with a few thoughts about the function of these weekly meetings. “The work you show in crit is a way to share your inquiry,” she advised, and a “way to broaden your discussion with others.” She suggested to the whole cohort to “giv[e] yourself permission” to follow different artistic paths during graduate school, then step back and edit with a keen awareness of when to auto-filter.

While the respective critiques of Painting + Printmaking and Sculpture + Extended Media share foundations that are essential to an artist’s growth, notable differences between the departments emerged when I attended Visiting Faculty A. L. Steiner’s Wednesday evening critique. This session focused on the work of two students: Shana Hoehn and J. Avery Theodore Daisey Collins. Hoehn presented a twenty-minute video about ambiguity and apathy with meditative camerawork that shifted between a domestic space and a medical classroom, in which individuals stared with indifference at a life model. Although a work in progress, Steiner suggested that the class take the video as is. Rather than a free-form conversation, Hoehn introduced her work and asked for specific feedback about questions she was working through: the video’s use of language, the characters’ interactions with each other, as well as the camera’s movement. The group spent a few minutes gathering their thoughts on paper, and then Steiner began by proposing that “a literal first impression would be helpful.” Most of the feedback addressed technique and narrative; in this case, nuanced considerations served to tease out larger ideas. Collins’s multimedia installation offered a variety of websites, videos, and sculptures that challenged patriarchal hegemony through a dual strategy of alienation and humor, all dosed with uncanniness. They introduced the work with a more poetic statement, starting a discussion that drifted from formal concerns to the Nineties-era nostalgia coursing through Collins’s art. The students appeared particularly enamored with Collins’s websites, which they presented on four desktops, allowing users to click through absurd digital spaces that lampoon images of masculinity. The group conveyed a greater sense of unease about Collins’s grainy video installation of hands squeezing milk from an individual’s breasts (Collins placed bottles of milk and a sign reading “FREE SAMPLES” next to the television). While remaining respectful, critique became particularly tense when Steven Randall, wondering about the work’s apparent brazenness, posed the adage, “Is it easier to trap flies with vinegar or honey?” In other words, with what degree of force should a work of art confront viewers? What are the advantages and disadvantages of nuance and directness? As the four-hour critique concluded (about two hours for each student), the conversation remained open-ended. Later Collins described Steiner as “an incredible mediator” in critique who can “generate some sense of a progression so that the group does not get stuck on semantics, a fragment of the work, or some confusion.” Reflecting on the evening’s debate about the work, Collins concluded that “as combative and confusing as critique can be, I find its existence … keeps me pushing, smashing, yelling, and questioning my place not only as an artist, but as a queer-feminist-womyn artist.”

On a structural level, VCUarts Dean Joseph Seipel envisions an institution that matches the trajectory of the global art world. The edges of disciplines, like once-sovereign borders, “are getting fuzzier and fuzzier and starting to morph,” observes Seipel. On par with the interdisciplinarity promoted by other institutions like UCLA and the New Museum’s incubator New, Inc., Seipel wants VCUarts to “reap the benefits of being part of a comprehensive research university.” While innovation and entrepreneurship are palpable conceits around campus, which Seipel deems crucial to the MFA program as well, he still makes it clear that VCUarts is not interested in dumbing down studio practice, which he sees as fundamental to the school’s ethos and vision. Curriculum aside, a school must truly understand that in a post-Roski moment, if it wants to adequately prepare its MFAs for life after school, affordability will be crucial. How can artists pursue their vision of success and move to Berlin or Mexico City (let alone New York) if burdened with a hundred thousand dollars of debt? Across departments, many MFA students, if not most, receive funding for both years. Being a public school, if a student does have to take out loans for a year, out-of-state tuition will run them around $25,000. Yes, this is still a lot of money. But compared to other top MFAs, it is much easier to digest. Affordability indeed will be to the benefit of VCUarts in the future. Rising above all else, however, is the real sense of community that the school and location foster. As an art history student there, my time roaming the school’s halls has been accentuated by the frequent interactions with artists, who energize the MFA program’s openness and conviviality. Perhaps at this local level, outside of imagined centers like New York, the student of art has the time and space to truly matter before choosing the art world they want to inhabit.

—Owen Duffy