Less than a year after the appointment of new chair Howard Singerman, a major relocation to 205 Hudson Street in Tribeca, and significant changes in administration and faculty, Andrew Cappetta considers Hunter College’s recent transformation in light of its rich history of graduate art education—one which isn’t readily acknowledged by the broader art world nor widely advertised by the school itself. In conversation with the new administration, Cappetta considers the program’s current institutional and pedagogical direction. Artist and writer Tyler Coburn investigates, visiting Hunter’s classrooms and speaking with current MFAs and recent graduates, to offer a view of the institution from their perspective.

Rehousing an MFA

—Andrew Cappetta

One of the vestiges of Hunter’s history still looms outside the 68th Street campus, Tony Smith’s Tau (1961-62), a black painted steel polyhedron that functions as a foreboding gateway. While Smith’s time at Hunter has left an indelible mark on the site of the school, many others graced the Art department in the 1950s and 1960s, including working artists such as Robert Motherwell, Ad Reinhardt, William Baziotes, and Richard Lippold, and established critics like E.C. (Gene) Goosen. At this moment, Hunter provided a place for the transition from New York School-style painting to Minimalist art practices. It is where Robert Morris (who only recently retired from teaching at Hunter himself) researched and wrote his Master’s thesis on Constantin Brancusi, leading to his concepts about sculpture as site. It is where Robert Barry picked up on Reinhardt’s example, developing a minimalist painting practice, which eventually dematerialized into concepts communicated by text. However, in the 1950s through the 1970s, studio practice was ensconced in the MA program. Hunter only established an MFA degree program in 1979, a change in institutional infrastructure and size, which required more space. Soon, the MFA was jettisoned from 68th Street to a city-owned industrial building tucked behind the labrynthine Port Authority Bus Terminal complex.

In 2013, the program traded in the enormous scale and relative autonomy of 41st Street (it was described by many as a “pirate ship”) for four sleek, refined floors in newly-renovated (and highly-regulated) building at 205 Hudson Street in Tribeca. A newly appointed chair coincided with the relocation—Howard Singerman arrived at Hunter this past fall from his post as the chair of the McIntire Department of Art at the University of Virginia. Singerman sees the new building as a boon that “will bring the program increased visibility,” admitting that, up until this point, “it has been a stealth program, a local program.”

Here, “local” can have two inflections: those who merely live here in New York (including the cosmopolitan elite), and those socio-economic groups who are under-served in favor of the cosmopolitan elite. According to Singmerman, the inexpensive tuition (about a third to a quarter of the price of other New York area MFA programs) produces “a much more economically diverse student body,” i.e., it attracts this more broadly-defined “local.” But would this “increased visibility” compromise Hunter’s ability to serve all of New York, the under-served and the well-heeled? Will this change as the cosmopolitan elite comes to constitute more of the “local”?

In fact, the Hunter MFA program is already global in reach, pulling from the national/international pool of art workers who might spend days as studio assistants or museum employees, and nights and days off in the classroom or their own studios. Faculty member Malik Gaines (of performance art troupe My Barbarian) remarks, “[Hunter] is more integrated into the life of the world, and less of a residency getaway.” However, the program has recently instituted a three-year cap for part-timers, which might change the make-up of the program’s participants, attracting less of those who have serious commitments outside of their studies. Gaines suggests that this has been a point of contention, noting, “As the professionalizing forces are discussed, many of the faculty who have been here for a long time really want to protect the way that Hunter’s MFA has traditionally been something that you could do while working, or while having a family, or at your own pace.” He firmly adds, “We are not just a service to the elite.”

Prior to Singerman’s arrival and the move to 205 Hudson, the program had already made significant changes in its faculty. In 2007 Paul Ramirez-Jonas joined the program, and in 2011, Gaines, Daniel Bozhkov, and Carrie Moyer were hired. With these four, Hunter seems to possess a distinct focus on social practice, performance and writing. Singerman admits, “What I actually knew least about is Hunter’s tradition, that of color abstraction.” In his estimation, “We are getting less of a Hunter style. It will still be a place to go for painting…[but] clearly with Malik, Paul, Daniel and Constance De Jong, there is an increasing interest in combined media—installation, performance, video, digital projection, and writing.” At a recent Open Studios, a commitment to object-making and combined media was evident: a painting became a backdrop for a tableau vivant, flat screens became sculptural material, projections animated 2-dimensional work. Some of the most notable (and marketable) Hunter MFA graduates of the past two decades include multi-disciplinary artists such as Paul Pfeiffer, Wade Guyton, Cheryl Donegan, and Omer Fast, whose practices bridge painting and digital media, video and sculpture, narrative fiction and documentary. Perhaps, “combined media” is not a new emphasis in the program, but rather the new Hunter “tradition.”

Despite the intentions of institutional and pedagogical rhetoric, the question still remains: how are these architectural and bureaucratic transformations shaping the lives of Hunter’s students?

Re-skilling the Artist

—Tyler Coburn

An hour into Daniel Bozhkov’s graduate seminar, four students begin leading the class on a breakneck march through postwar art. Powerpoint slides of Duchamp, Barthes and Marx interchange with textual breakdowns of “Work Ethic,” Helen Molesworth’s formidable publication and exhibition on the ‘60s and ‘70s. By the time the final presenter gets up to speak, the visionary artist has given way to the culture worker, autonomy to professionalism; deskilling is spreading like a lingua franca, prompting the student to take a reflexive turn.

“If one set of skills falls away,” MFA Noah Furman considers, “what’s thrown into question is: what do artists do? What is their labor—the value of their labor? Along with the proliferation of MFA programs and MFA artists, whose main training involves talking—sitting around in rooms, looking at things, becoming trained to eventually teach at MFA programs—the re-skilling seems to be thinking.”

Nervous laughter ensues.

Furman delivered these observations with apt cynicism, suggesting the invigorating yet often incapacitating onus of the MFA: at best, to pursue critical and autocritical maneuvers (at worst, to stare fixedly at the navel). While pedagogical practice has long made discursive fodder for theorists and educators, a recent spat of writings is shifting focus to the material realities of graduate school. Occupy Museums, for example, issued an “Open Letter to the Deans of Art Programs” last summer, on the eve of Congress’s failure to prevent the doubling of Stafford student loan interest rates. Citing the “toxic effect” of debt, the organization encouraged deans to work to increase institutional transparency and freeze tuition rates.

In an essay from the December issue of Modern Painters, Coco Fusco weighed the benefits and deficits of pursuing graduate education. The artist drew on her considerable teaching experience, raising pointed questions about the use (or misuse) of theory in arts pedagogy, the sobering prospects for postgraduate employment, and the attendant financial challenges. (Fusco cited a claim, from a 2013 Wall Street Journal article, that students at art-focused schools incur the greatest debt).

The title of a forthcoming reader poses the question in simpler, starker terms: Should I Go To Grad School?

The Hunter MFA is not immune to these economic realities, though distinguishes itself in offering affordable tuition and the possibility of three year, part-time enrollment. “Jim,” a third-year student speaking anonymously, was accepted into a handful of prestigious art schools with hefty price tags; he chose Hunter instead, because “what you’re paying for is basically the equivalent of getting a shared studio in Bushwick.”

“When I decided to apply to grad school,” reflects second-year student “Sam,” “I knew I didn’t want to pay. There was no point, relative to the professional money the degree entitles you to.” Sam was not able to secure a full scholarship at an art school, so decided on part-time enrollment at Hunter, which enables him to work alongside his studies.

Sam’s case is a common one. “The thing it boils down to is that I’m a working artist and I teach working artists,” remarks MFA faculty Paul Ramirez Jonas. “They all have jobs—undergraduates and graduates alike. So the social contract is very strong.” Prior to coming to Hunter seven years ago, Ramirez Jonas adjuncted in schools throughout the east coast. Learning the ins and outs of both art school and university models helped the artist identify problems shared by private institutions: a lack of economic class diversity, for example, and rampant grade inflation, which often made him feel “like my students were customers.” Notwithstanding its oversize bureaucracy, a public institution like Hunter comparably benefits, he claims, from its “porosity with the real world.”

Ramirez Jonas’s hire figures into larger shifts in the MFA faculty, spanning Lisa Corinne Davis’s entry in 2002 to Bozhkov, Malik Gaines and Carrie Moyer’s in 2011. Beyond introducing an unprecedented level of diversity, these professors bring knowledge of conceptual art, performance and social practice that the department sorely lacked. Moreover, as with Ramirez Jonas, they gained teaching experience working in a number of different institutions.

“I don’t think this is unusual,” Davis remarks, “but historically, Hunter was hiring its own.” With limited pedagogical templates and shared aesthetic interests (the school was once associated with color field painting), the existing faculty didn’t put a lot of thought into “doing things that weren’t just within the Hunter canon.” A number of retirements within recent years has allowed for the new hires, though technically, Ramirez Jonas notes, the faculty is still four short—a lack the 136 current MFAs acutely feel.

“There are not enough professors for the students,” Sam complains. He and others also express frustration with a registration process that (as in many schools) operates by seniority. “You don’t actually get to work with the good professors until you are on your way out,” notes full-time student “Kate.” Competition for certain faculty engenders what Jim characterizes as “resentment and bitterness” from less desirable professors, which can “filter into student relationships,” based on whom one is working with.

Despite the evident frustration, MFAs are eligible for three semester-long tutorials with faculty members, each comprising at least six individual meetings. Students must take these tutorials alongside seminars, which can vary drastically between professors, but largely center on critique. Gaines’s current seminar routinely begins with participatory exercises drawn from political theater games—many of which also inform his work within My Barbarian. These exercises “investigate group dynamics,” Gaines notes, and also “introduce social and theater” terms that students take up in the second half of the semester, when they propose theater, public or community sitings for their artwork.

Bozhkov’s aforementioned Combined Media seminar usually entails a few exhibition reviews, student critiques (“assisted” by peer facilitators) and famously extravagant breaks. “There’s an unsaid expectation that people bring top-notch food,” explains first-year student Paige Walton, who serves as an unpaid teaching assistant for the class.

Given that graduates are eligible to teach in higher education, pedagogical training is an expectation of many MFA candidates; the present lack of paid TAships, Ramirez Jonas notes, is thus “really a problem.” “We have almost no money to give to our students,” he continues. “The only thing we can offer them, beyond being cheap, is that they can go part-time, which makes the school even cheaper.”

In addition to seminars and tutorials, a typical MFA student course load also includes at least three Art History classes, one of which focuses on theory and criticism. The shape of this class largely adapts to professorial interests (Gaines’s fall section, for instance, focused on “Theories of the Body”), yielding a diverse but qualitatively divergent series of approaches. Kate recalls finding the “huge amounts of reading” from her course systematically reduced, in class, to “one-liners.” Seeking clarification about the denser passages of a text, she was told that she only needed to know enough “to understand the references in Artforum.”

Kate concedes that her experience may be “an anomaly,” citing The Artist’s Institute seminar as an exemplary case of reading texts—and artists—in depth. Initiated by Anthony Huberman in 2010, the off-campus Institute devotes six-month long “seasons” to the work of a given artist, filled with public programs, private events for the Hunter community, and weekly, discursive classes for MFA and MA Art History students.

“I personally believe that the university gallery is the great untapped resource of the century,” remarks current curator Jenny Jaskey, “and The Artist’s Institute is one way of configuring pedagogy in a gallery setting.” In addition, she continues, it challenges “the idea that everything an institution does has to be for the public.”

The Hunter-oriented programming is notable, to Jaskey, for emerging in partnership with the students. One of the art historians in Lucy McKenzie’s fall seminar, for example, was also working on Sol Lewitt’s catalogue raisonné. She observed the artists’ shared interests in murals, inspiring the hire of one of Lewitt’s longtime draftspersons, who led students in creating an actual work in the Institute. Contemporaneously, students arranged a walking tour to all of the Lewitt murals throughout the city.

Such student initiatives are a necessary motor for the Hunter MFA. Davis partly attributes this to the nature of a public institution, where the challenges of bureaucracy and the financial constraints compel students to “act more like they are part of a grassroots organization, rather than a corporation. Glibly put, they’re not prima donnas.”

When the program still occupied the building on 450 W 41st Street, recent graduates Maya Jeffereis and Matthew Cianfrani established a Digital Media Collective (DMC) to oversee the rental of the scarce equipment, as well as bolster a community of media-friendly MFAs through workshops, studio visits and public events. In these massive quarters, which spanned six floors of a former Technical Institute, students transformed unused space as needed. Kate remembers The Print Shop Collective forming by such means, with members paying fees to buy and replenish equipment. “Whatever Hunter couldn’t provide, facility-wise,” she says, “students were making.”

Jeffereis describes the “anything goes” mentality of the old MFA building: Hunter had long ceased regular maintenance, leaving its dilapidated rooms open to the whims and wills of the residents. “One student turned his studio into a birdcage,” Jeffereis recalls, “and you could look through a peep-hole to see the birds in their habitat. Another couple of students [Oasa DuVerney and Jonathan Elliot] had a hot food restaurant going in their studio.”

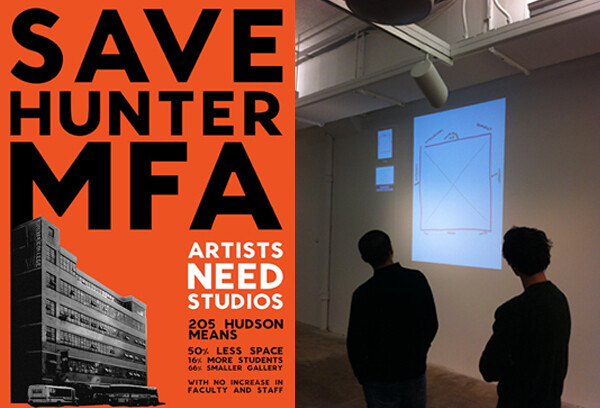

“The subjectivity and psychology of the program was really rooted in that building,” Sam remarks, making its recent move to TriBeCa the subject of ongoing speculation and debate. “We were never really given a reason why we were moved to a space that’s three times smaller and really expensive for the city to lease,” Ramirez Jonas remembers. “Officially, the school told us that it was too expensive to renovate 41st Street, but we spent a similar amount renovating 205 Hudson, and they leased that building.” (The university held the 41st Street property for free.)

Students and faculty actively campaigned to retain the former facilities, and some of those efforts are featured in 450 W 41st Street, a recent publication by Pirate Press. Created by MA Art History graduates Christopher Rivera and Misa Jeffereis, the publication includes interviews with MFA Program Director Joel Carreiro and longtime professors Andrea Blum and Juan Sanchez, as well as sundry contributions from former and current MFAs.

In its concluding pages, 450 W 41st Street focuses on the campaign: first, a 2008 Open Studios postcard of naked students who, with equal parts sass and mock-lament, hold a banner reading “HELP!” An open letter to Hunter President Jennifer Raab follows (one of several archived here), as does a thoughtful text in which MFA graduate Rachel Higgins proposes, “[T]he question that’s really at stake here is simply how our public institutions function and for whom they function. We are moving on, but what was at stake then is still at stake now […] What is our capacity to push back against this never-ending privatization and capitalization of our public space?”

Many still wax nostalgic for the days of unhindered play, though few would deny that they came with serious environmental drawbacks. “The old building had a lot of romance and a lot of space,” Ramirez Jonas remarks, “but who cares how big your studio is if you can’t use a third of it due to a leak, or if it’s too hot to work in during July and too cold in January? Who cares if the crit rooms were twice as large, if you had no proper lighting and needed to scream because of the acoustics?”

While the pristine 205 Hudson more than resolves these issues (and places students within a stone’s throw of Beyoncé), it also presents serious challenges in terms of available space: for example, with one flexible-use room in lieu of the former six. “It’s now like a restaurant,” MFA faculty Reiner Leist observes. “The space has to be used three or four times a night.”

Artist studios have also slimmed by necessity, and students are ambivalent about the possible effects. “You’re going to see smaller things that are more geared towards the logic of commodities,” Sam dryly remarks. While graduating before the move, Jeffereis concedes that the previous building was “unrealistic” relative to the opportunities that MFA candidates have upon graduation, both in terms of studio space and exhibition opportunities. “The work students now make,” she predicts, “will be New York–sized.”

“I wonder if the program will attract a different student,” Gaines imagines, “coming and visiting this fancy space.” Other evidence would suggest that the new faculty—including recent hire Howard Singerman—is having a more influential effect. Chatting after a day of interviews, Davis recalls that the majority of applicants expressed interest in working with “a diverse faculty, so they didn’t feel pressure to make a certain type of work, or think a certain way.”

Jim sees this as a great strength. “The program doesn’t have a central, critical directive like others do,” he remarks. “That’s why I chose it.” When asked about Singerman’s potential influence, he mentions a lecture the new Chair delivered in the fall, entitled “A Reserve Army of Intellectuals.” “For him, the hallmark of a good arts program is that it’s constantly critiquing itself,” Jim notes, going on to observe that Singerman “has a nurturing view of the program.”

Interviews coincided with Hunter’s spring Open Studios, enabling MFA applicants to see current candidates in their newly adopted habitat. The official literature celebrated the students’ organizing zeal, from the Digital Media and Photo Collectives to Vers, a fledgling queer collective operating under the advisement of Gaines.

In its recent move, the program received a wealth of new equipment, making collectives like the DMC question their ongoing necessity. Jeffereis recalls that current Co-Director Izabela Gola “decided it was something she wanted to continue because of the ‘community’ it created.” Beyond offsetting the historically scarce resources, MFA groups also seem intent to form such micro-communities, in an effort to mitigate the alienating effects of a large student body. Jim, for example, characterizes the external perception of Hunter as operating like a “massive factory,” in which a “cold, indifferent” mood prevails. “In the sense that factories are defined by clear regulation,” he remarks, “the program is the complete opposite […] There are pockets of things happening at all times, and there’s an influx of students every semester.”

Nonetheless, some students express concern about Hunter’s relationship to MFA groups. The institution may offer more facilities than ever before, but can its celebration of student organizing provide implicit grounds to continue to underserve its candidates, lest that grassroots ethos dissipate? Does cheap tuition give enough incentive for a student to overlook the blunter edges of Hunter’s pedagogy?

The social imperatives of collectivization may always render such concerns secondary. Vers, in Jim’s opinion, owes its existence to students who came to Hunter expressly to work with faculty like Gaines. The next wave of organizing may also respond less to material than discursive concerns. If an MFA re-skills an artist in the craft of thinking, in short, then the Hunter MFA presents both the resources and the challenges necessary for community building.

The Hunter Department of Art & Art History is a union of three distinct areas—Art History, Studio Art and the Galleries. Students can practice many media, can study art history and theory, and can help curate shows and write catalog essays, gaining practical experience as well as knowledge. This holistic approach, seeing the department as a manifold of activities and study opportunities students can selectively engage and take advantage of, is a distinctive aspect of studying in the Department of Art at Hunter College.