http://www.dieangewandte.at

A program “for all” is a formidable promise to make, yet this is what Andrea Lumplecker, an artist and long-time producer of art and educational programming, has achieved for Vienna. Among the more daunting questions Lumplecker had to address during an eight-month planning phase that began in early 2021 were how to shape this class for all, what to teach, according to what schedule, whom to include as educators and participants, and how to reach the public. Provided by the University of Applied Arts Vienna (the Angewandte) with a modest budget and space in Heiligenkreuzerhof, in central Vienna, Lumplecker’s task became clear: to make available to the public the educational resources and learning opportunities enjoyed by the university’s students and faculty. And so, in October 2021, the Angewandte and Lumplecker officially launched the open-access continuing-education program Klasse für Alle.

A Class For All and From All

Initially situated in the Angewandte’s Institute of Arts and Society, the Klasse has since gained the status of one of the fifteen institutes and labs at the university, increasing its public visibility and complementing the school’s existing focuses on art, design, science, and technology. 1 Still, the missions of the Institute of Arts and Society and the Klasse remain deeply entwined: both seek to drive social transformations through art and are keen on experimenting with hybrid forms of artistic practice, cross-disciplinary strategies and methods, and multivalent categories intersecting art making, knowledge production, and societal changes. Both are rooted in advocacy for the nonmodern, as laid out in Bruno Latour’s 1991 book We Have Never Been Modern, an inspiration identified in the Institute’s description, to respond to the problematic modern divide between nature and society.

Regardless of the institutional arrangement, one emphasis was clear to Lumplecker from the beginning: Klasse für Alle would be a nonhierarchical learning platform, for people from all backgrounds to learn from and with each other. The formation of a cohesive cohort and the encouragement of fruitful discourse among organizers, instructors, and participants evoke artist cooperatives whose management and practices solicit ideas and proposals from all members (but usually members only), the rejection of hierarchy in the arts, and the fostering of communal practices in avant-garde movements like the Bauhaus. However, as Boris Groys writes, despite their vision of and openness to universality, radical art and political movements often make prerequisite an “aesthetic preference for the uniform” that is “very unpopular, very unappealing to the masses,” resulting in the creation of “closed communities based on common commitments.” 2 In contrast, the Klasse’s stated position as being for all is less an artistic or political commitment or a project shared by few leaders than a practice of reflection and organization. In the Klasse, all sorts of roles and responsibilities are conflated, and participants can easily become instructors of their own learning programs. Indeed, Isa Klee, a dedicated advocate for biodiversity who is self-taught in botany and biology, first joined as a participant in “Repair,” the Klasse’s 2021–22 program, and now leads the biodiversity module in “Garten für Alle,” the 2022–23 program. Similarly, seamstress and artist Erika Farina and artist and cultural worker Johanna Preissler participated in the Klasse’s Artivism Reading Group and have since led the collective sewing and weaving workshop “Braiding Community–Common Ground.” 3 The textile work developed in this workshop offers a model of the Klasse: scraps of fabric assembled by participants have been stitched together and expanded into a spiral-patterned carpet, which, when exhibited at the Klasse’s 2022 open house, offered a even field and supportive foundation for everyone to gather.

For the class to be truly inclusive, outreach has remained a core task. Public and community channels, like Ö1 of ORF, the Austrian national public broadcaster, and Radio ORANGE 94.0, have helped introduce the program to different audiences, especially those outside of Austria’s art and educational circles. Program instructors, too, have brought in their specific audiences and together have grown a network of enthusiasts in drawing, gardening, craftwork, and somatic practice. In “Braiding Community–Common Ground,” in 2022, for instance, immigrant mothers involved with the “Mama lernt Deutsch” (“Mom Learns German”) course comprised a major group of Klasse participants. 4 The kind of just and inclusive program that the Klasse fosters thus entails identifying and caring for participants’ individual needs and reckoning with differences in their socioeconomic and national backgrounds as well as their responsibilities as caretakers and community members. Inclusion has also informed Lumplecker’s vision for the Klasse’s long-term financial self-sufficiency: after experimenting with free, fixed-price, and pay-as-you-wish admission, for the current semester Lumplecker implemented a tiered ticketing model for single events that extends access to the general public for as low as five euros and free entry for those in need. 5

Cracks in the System

As part of the Angewandte Festival, at the end of June 2021 Klasse für Alle tested an “open window” event, a preliminary encounter with the public before embarking on “Repair,” the Klasse’s first semester-long program. Hoping to introduce the class to Vienna but mostly thwarted by strict Covid policies that denied public entry to the university’s premises, affiliates of the Klasse set up chairs by an open window and in the courtyard of Heiligenkreuzerhof. This arrangement, however, lent the encounter the sense of informality of friends dropping in for a chat. With caution and excitement, so began the “Window Talks” (“Fenstergespräche”) between public visitors and the Angewandte’s students and staff, which produced a series of notes and sketches on the nascent Klasse’s future orientation, including the pertinent questions “Who is everyone?,” “How can the university open up?,” and “How do we want to learn?”

Let us not rush to draw connections between the inaugural theme of “Repair” and every struggle and crisis that Covid presented. Cracks in the educational, epistemic, and sociopolitical systems, on local and global levels, existed before 2020 and beyond the pandemic. Repair is one of the most urgent tasks of our time and forms the foundation of the Klasse’s work in equitable education. Citing the French-Algerian artist Kader Attia, Lumplecker’s initial proposal to the Angewandte positioned repair, as a form of renewal, healing, and care, at the center of the Klasse’s mission. In Attia’s concept of repair as a constant decolonial project, care is correlative and multifarious and tied to art and epistemology. In a 2021 conversation with art theorist Nina Möntmann, Attia recast the artwork as the caretaker of its viewer by creating depth and slowing time and the museum as the custodian of its collection and debates on restitution amid the damages of colonialism. 6 A society’s psychological health, without exception, needs care. Attia’s conceptual, artistic, and pedagogical exploration has inspired the program to lay out several approaches to care and repair, notably around sustainability, mindfulness, persistence, resilience, and togetherness. 7 Repair, as an agenda and in the pedagogy of the Klasse für Alle, is not about hiding wounds and damage but rather about making such cracks visible and creating awareness of their harm as the first step in a healing process. Remedy, or discussion on the methods of remedy, comes next. Quoting Attia, repair is “an endless movement” and “really everywhere,” and in this spirit, Klasse für Alle has operated within the cracks and divisions in households and societies, the gaps in knowledge access between contiguous groups, the aftermath of historical injustices, the grievous or unattended wounds of colonialism, and the distress of the immediate past of the pandemic and environmental catastrophe.

The ten-day kick-off program for “Repair,” in October 2021, opened with the introduction of Treecycle’s “city furniture” (“Stadtmöbel”)—which grows trees in recycled industrial containers equipped with benches—and the first meeting of the environmental action group. On the following day, artist Anab Jain, of the collective Superflex, led a tour of their exhibition “Invocation for Hope” at the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK), which was followed by the group’s action to return the trees in Superflex’s installation to nature. Other events included a guided walk in Donau-Auen National Park, a screening of Attia’s film The Postcolonial Body, and a workshop on mending clothes. On the third day, research artist Carla Bobadilla, a founder of the collective Decolonizing in Vienna (DiV), led a tour of the city’s Innere Stadt to identify and examine traces of Austria’s colonial history, part of a program in which DiV argues that any learning is always an unlearning of colonial prejudice and hegemony. 8 Focused on the history of trade and botany, Bobadilla drew attention to building facades, monuments, and business premises that were tied to colonial exploitation, which together showcased and produced the category of the Other. 9

A critical encounter with the everyday urban environment was also created in “Cracks in the System,” another city walk undertaken by the Klasse in November 2021 and led by Aurora Zordan of the Architectural Association (AA) Nanotourism Visiting School, an experimental teaching and site-specific research program based in London. 10 Before arriving at possible answers to the question “How can wild and unregistered trees provide a new form of ‘climate literacy’ and an alternative greening strategy for the city?,” the group first had to locate these rogue specimens. 11 Knowledge of their whereabouts was inherited in part from an earlier event in the Viennese district of Meidling developed in 2020 by the AA Nanotourism Visiting School and Vienna Design Week and involving biologists, tour guides, politicians, and residents. The joint effort of surveying the city enabled the identification and documentation of self-planted trees that exist outside of Vienna’s official register, and, as Zordan proposed, led to a discussion of the insufficiency of existing “urban greening” models in addressing the climate crisis. For the “Repair Assembly,” the Klasse’s Artivism Reading Group discussed texts from María Puig de la Bellacasa, bell hooks, Donna Haraway, and adrienne marie brown, among others, the lessons of which combined with the practical open studio “Repair Together.” 12 Here, one learned to repair socks, sweaters, furniture, and the natural environment. Reading sessions prompted participants to get to work, and then pause, take a step back, and reflect on the meaning of their reparative actions.

An Open Garden

Following Donna Haraway’s conception of the human as humus from Staying with the Trouble, “Garten für Alle,” the Klasse’s program for the current 2022–23 semester, blends diverse coordinated activities with a touch of spontaneity. 13 At Zukunftshof, a historic farm complex in Vienna’s Favoriten district, participants have walked its fields, identified plant species, planted trees, and discussed topics such as soil health and microclimates. Choosing gardening as a program theme seems a natural development from a year of activities focused on repair. “Garten für Alle” has offered opportunities to address the climate crisis, the challenges of urban greening, and a lack of knowledge of the natural environment in contemporary education, which persist from elementary to tertiary levels. Despite its historical association with nature and comfort, the garden, as a site, has not always embraced all demographics with open arms, and Lumplecker has highlighted the garden’s potential as a “communal space between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’” while pondering the precarious public access to gardens and parks. As national pandemic restrictions demonstrated, leisure activities in outdoor public space remain subject to contestation and control. Several large federal parks were closed during the lockdown of spring 2020, while those in the city remained open, and the uneven distribution of green, open space in urban areas amplified the disparity of access; in urban parks, exercise was permitted but more leisurely activities were not. Lumplecker has further connected the permeating unease in using public facilities, a result of people being “thrown back on privacy” during the pandemic, to the exacerbating, recurring summer heat waves that make escape from the city a privilege. 14

In “Garten für Alle” sessions, Johannes Wiener, an artist, architect, and gardener who serves on the Klasse team as a garden consultant and instructor, has argued that exclusion is fundamental to the formation of gardens. A garden is essentially an enclosed yard or a hedge, which Wiener has noted is the meaning of the proto-Germanic word “gardo.” 15 The dilemma of access and exclusion is thus inherent to the garden: demarcation is historically integral to the capacity of enclosure and care but at the same time prevents the garden from becoming an entirely communal space. Can there really be a garden for all? Similarly, the Compost Group, another core module of “Garten für Alle,” works with tangible and metaphoric elements of gardening. Composting, in this context, combines physical labor, art making, and conceptual exploration of “gathering, acknowledging, and transforming.” 16 On Friday afternoons, a working group meets to compose the compost heap in the courtyard of the Angewandte, which in two years of development has come to take up an approximate two-by-two-meter patch that is enclosed by thin bamboo stakes and narrow strips and marked by a makeshift sign informing passersby of “Compost, please care.”

In one session I attended this March, the Compost Group began by reading aloud excerpts from Puig de la Bellacasa’s “Encountering Bioinfrastructure: Ecological Struggles and the Sciences of Soil” and Vandana Shiva’s Soil, Not Oil. One participant read from Shiva’s opening paragraph: “The climate crisis is a consequence of human beings having gone astray from the ecological path … acting like we are kids in a supermarket with limitless appetites for consumption and falsely imagining that the corporations that stock the market have unlimited energy warehouses.” 17 In response, a young architect reflected on her trip to Nepal, where she observed the disparate lifestyles among urban neighborhoods there, some more tranquil and locally scaled, others more ambitiously consumerist, with access to supermarkets and other conveniences of global capitalism. The comment brought to my mind the shelves of modish heirloom tomatoes and eggs in supermarkets. A participant mentioned that women hug trees to obstruct lumbering in India’s Chipko movement against deforestation, a major inspiration for Shiva. It struck me that the group was chiefly formed by young female artists, architects, and other cultural workers, some of them university students, others not. Another participant explained the intriguing story of Shiva’s training in quantum physics and involvement in climate activism, as well as the principles of the former that informed the latter: interconnectivity and indeterminacy. Then, the group moved to expand the composting structure while another team continued the previous week’s work designing and crafting a wooden box to contain the freshly finished humus. As envisioned by the group, the created objects are both functional and aesthetic and concerned with life cycles and transformation. Puig de la Bellacasa’s writing from the reading session echoed in my mind as I stirred up the compost, a mixture of fresh humus and yet-to-decompose organic matter: “If we look at the category of archaeological evidence from a contemporary ecological perspective, waste resistant to decay becomes a highly ethically charged category of matter. In short, if it cannot become soil, we have a problem.” 18 I tried to pick out the problems in front of me.

Across the street, on the city’s public lawn, Klee sowed seeds with her group—woodland sage and yellow mignonette—as a part of the biodiversity module. 19 In the past year of the Klasse, Klee has avidly spoken about the urgency of a biodiverse city, an aspect often overlooked in urban planning. The seeding group was of much broader demographics. In the drizzle and breeze, one participant cheerfully remarked, “The rain is just in time. We’ll call it a day,” with Klee adding that the rain would now take care of the seeds.

Common Ground

The question I returned to often, working with compost and plants, was not of the relevance of programs like Klasse für Alle, which are necessary everywhere, but of the assessment and validation of knowledge. In composting, by piling up, mixing, watering, and breaking down the heap of leaves and fruit peels, I was a coworker of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and time. We produced humus together. I provided care for the compost, which the compost would return as garden soil, but this activity would not be considered a typical pedagogical exercise. If we can understand the garden as a paradoxical site, the inclusive fenced-off yard that demands and provides care, could we not also see the university as such a place? By developing an open-access educational program, the Klasse raises the question of what an art university has to offer. Let us then trace the Klasse’s search for common ground.

While keeping busy across the multiple sites of “Garten für Alle,” Wiener explained the source of his knowledge. One is a specialized horticulture boarding school nestled in the park of the Schönbrunn Palace, where courses on soil, wildflowers, and shrubs are offered together with practical training in the garden, which is also connected to state-administered research facilities. The other is a childhood influence from his grandfather, who was heavily involved in Naturfreunde, the environmental organization established in 1895, the name of which literally translates to “Friends of Nature” but is more commonly understood as “Nature Lovers.” Associated with Austria’s social democratic movement, Naturfreunde has aimed to facilitate the inclusive exploration of nature by building infrastructure like hiking trails and huts and, throughout the twentieth century, campaigning for public access to mountains and forests. In the initiatives that informed Wiener’s approach, the production of knowledge about the environment was inevitably blended with the various agendas and shared goals of the school, the state, the political party, and the nonprofit organization. A common ground is necessary among them for knowledge and experience to be shared, interpreted, and expanded.

Another valuable endeavor is school, an art space and collective Lumplecker cofounded with artist Yasmina Haddad in 2011. The central “performative screenings” series has presented nearly eighty events by international artists over twelve years, foregrounding performance and relations to social reality. One example is the most recent “performative screening” by the artist collective Mai Ling, whose feminist and anti-racist vision is encapsulated in a cooking performance on stickiness. Gathered under the directive “Let’s stick together!,” the audience at Mai Ling’s performance pounded sticky rice together, experiencing joy and trust in a sensation unfamiliar and uncomfortable to many.

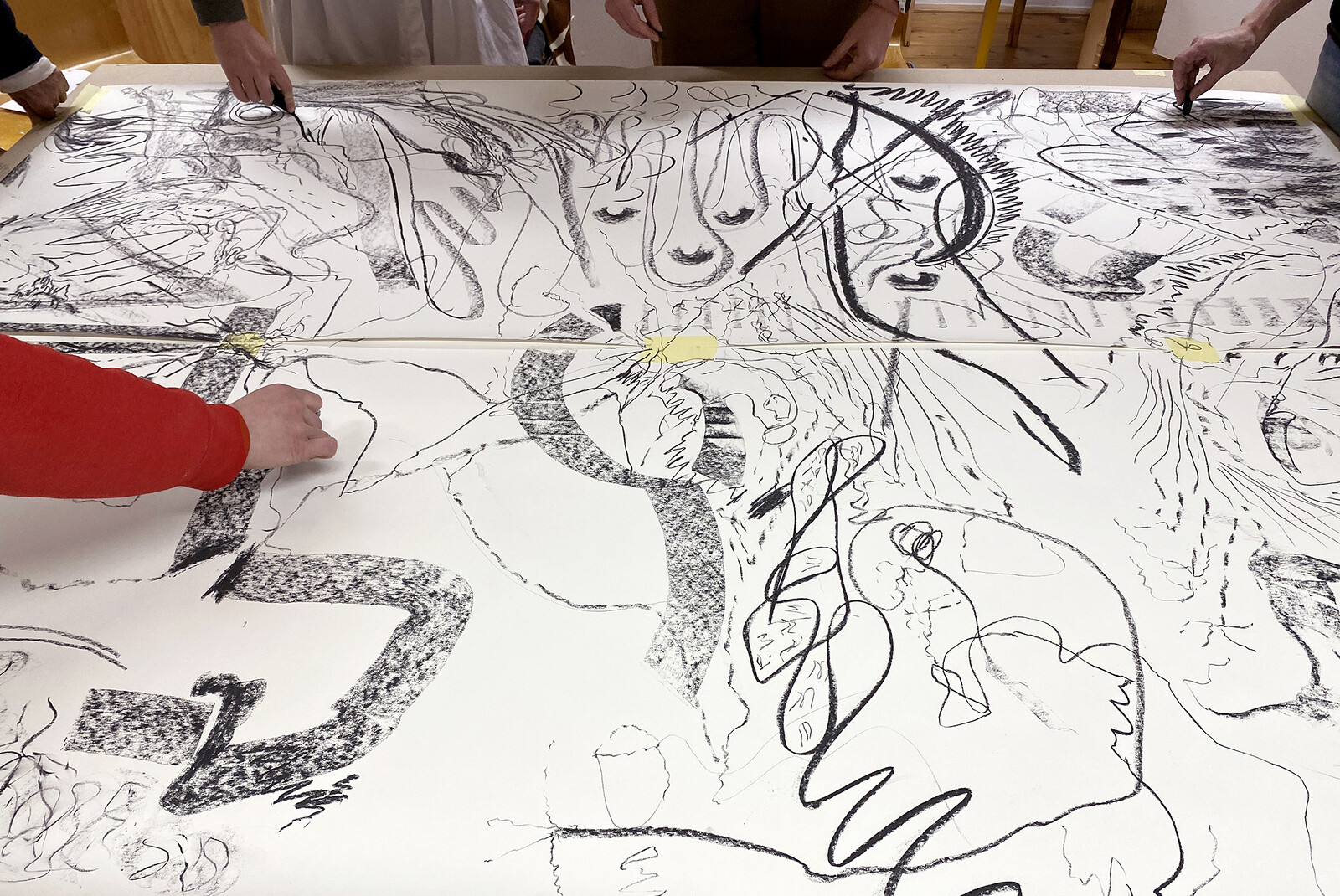

Reaching out from the art university, in comparison, requires the articulation of one’s position, Lumplecker reflected. 20 To be sure, the class is for all and, in particular, converges “global, anti-colonial, and queer-feminist” approaches. Meanwhile, Klasse für Alle shares room with what are framed as “more-than-human species,” like animals, plants, and microorganisms. Lumplecker remembered a moment in the first “Drawing with Others” session of the semester: interdisciplinary artist Elka Krajewska played a recording of blackbirds and a blackbird in the Heiligenkreuzerhof courtyard replied. The group—human and more-than-human members all—drew closer together, following, crossing, and weaving into each other’s traces. 21

I do not doubt the bond and appreciation formed in that beautiful moment, however fleeting, but in the end, as an educational program, on what or whose ground does the Klasse operate? The Klasse has never limited itself to the designated studio space in Heiligenkreuzerhof, and in “Garten für Alle,” it pushed toward in-between and public spaces: the courtyard of the Angewandte’s main building, the public lawn across the university, and the satellite farm complex of Zukunftshof. Considered by some early observers a self-serving publicity stunt for the university, the Klasse has certainly surpassed this misconception and located the cracks where its work is most urgent, whether in the university or the city. Its efforts concern not only the limitations of the art university but also the establishment of common ground between higher education, social welfare, and urban dwelling. What if working groups of artists, educators, gardeners, architects, climate activists, seamstresses, immigrant mothers, furniture repairers, and local radio stations could decide the purpose of the courtyards, gardens, parks, and plazas, and put themselves in the service of these public spaces? What if this group could reorient education away from the individual consumption of concepts and skills and toward the collective experiences of care, repair, and knowledge sharing for the commons. In these aspects, the Klasse für Alle has the true potential to transform itself and the university, as well as the spaces around it, into sites to coproduce knowledge and practice.

The head of the institute is Eva Maria Stadler, who has steered the development of the Klasse while leading the Angewandte’s Department of Art and Knowledge Transfer.

Boris Groys, “Beyond Diversity: Cultural Studies and Its Postcommunist Other,” in Democracy Unrealized: Documenta 11 – Platform 1, ed. Okwui Enwezor et al. (Hatje Cantz, 2002).

The Klasse traces the idea of “artivism” to the late 1990s political actions of Chicana artists in California and Zapatista artists in Chiapas.

“Mama lernt Deutsch” is a European Union- and city-funded integration program providing language and math classes and childcare to immigrant mothers.

Semester passes are also available at a higher rate, and supporters of the program contribute to the Klasse’s maintenance.

Over millenia, the objects the museum collects take the ultimate care of the people. See “The Decolonizing Agency of Repair: Objects, Epistemologies, and the Neoliberal Value System: Kader Attia in Conversation with Nina Möntmann,” Texte zur Kunst, July 14, 2021 →.

Klasse für Alle, “Statement on ‘Repair 2021/22’” →.

See →.

Klasse für Alle, “Archive: Repair” →.

The nanotourism program is a part of the AA Visiting School at the Architectural Association, School of Architecture in London. It critiques the environmental impact and participatory constraints of conventional tourism and seeks to innovate local economies.

Klasse für Alle, “Cracks in the System–Ein Stadtspaziergang mit Aurora Zordan” →.

Texts included Haraway’s Staying with Trouble, andrienne maree brown’s Emergent Strategy, bell hooks’s “Theory as Liberatory Practice,” Audre Lorde’s Poetry Is Not a Luxury, and the book Post/pandemisches Leben: Eine neue Theorie der Fragilität by Yener Bayramoglu and María do Mar Castro Varela.

In “Garten für Alle,” the description of the Compost Group cites Haraway: “We are humus, not homo, not anthropos; we are compost, not posthuman.” Haraway, “Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene,” e-flux journal, no. 75 (September 2016) →.

Andrea Lumplecker, “Klasse für Alle,” August 2022 →.

Andrea Lumplecker, “Klasse für Alle,” August 2022 →.

Klasse für Alle, Statement of the Compost Group →.

Vandana Shiva, excerpt from Soil Not Oil: Environmental Justice in an Age of Climate Crisis, Alternatives Journal 35, no. 3 (2009): 19.

María Puig de la Bellacasa, “Encountering Bioinfrastructure: Ecological Struggles and the Sciences of Soil,” Social Epistemology 28, no. 1 (2014): 29.

To introduce biodiversity and craftwork to younger audiences, together with Klasse’s participant Ritger Traag and Angewandte student Magdalena Stückler, Klee runs the “Stadtexplorer” (City Explorer) workshop since February 2023; the workshop is hosted at Vienna Hobby Lobby, a project that offers sports and creative classes for free to children and youths from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds.

Andrea Lumplecker, interview with the author, March 20, 2023.

Ibid.