Asia Art Archive (AAA) in Hong Kong recently hosted “The Collective School,” an exhibition and a program series exploring artist-driven and collective models of learning. Developed in collaboration with Gudskul, a Jakarta-based collective that runs a grassroots school for other collectives, the project provokes debates about the necessity and adaptability of collectives today. Amid the growing expectation for art institutions to address social change and learn from collaborative and self-organized initiatives, art collectives have become more relevant than ever. Here, Susanna Chung and Özge Ersoy, two members of the AAA team, discuss the exhibition’s unfolding and what they have learned in the process.

Özge Ersoy: Imagine: You walk out of the elevator onto the eleventh floor of an office building in one of Hong Kong’s old neighborhoods. Through the windows, you first encounter the city’s landscape. Focusing closer, you see a library, with tens of thousands of books nestled among artworks and archival documents about contemporary art collectives. You walk into a spacious reading room and see a large column with hand-drawn graphics highlighting some key values about the current exhibition. You read: knowledge sharing, learning from friends, and collective sustainability.

These concepts have been central to Asia Art Archive’s group discussions with the Jakarta-based Gudskul, our main collaborator for “The Collective School,” and eight other collectives: ba-bau AIR, Hanoi; BiSCA, Bishkek; Load na Dito and Salikhain Kolektib, Quezon City; Omnispace, Bandung; Pangrok Sulap, Sabah; Scutoid Coop, Kaohsiung; and Yayasan Tonjo Foundation, Yogyakarta. 1 Together, we asked: How can we shift the focus of art history from individual artists to communities? How do artists learn from each other outside of formal education and through collectives?

I’ve been excited about our collaboration with Gudskul, especially because they run a grassroots school for other collectives. For us, Gudskul’s model articulates a bold proposition about existing art-educational models: Art schools are often geared toward individual mastery, skill refinement, and career-oriented networking. In contrast, students at Gudskul are already members of existing collectives. They join other collectives to study historical precedents, discuss collective working models, and develop exhibitions and projects together. Eventually participants work as a collective of collectives.

Susanna Chung: After we invited Gudskul to collaborate on “The Collective School,” they asked us to contribute to their study program. We joined Batch 4, the program’s fourth year, to develop it together with Gudskul and the cohort. While Batch 1 to Batch 3 were held at Gudskul’s campus, where collectives lived and studied together, Batch 4 was held completely online due to the pandemic. Collectives emerge in response to their unique contexts, and while many of them share ideas on the sustainability of collectives and the creation of education platforms, they respond to their contexts with different artistic practices. Becoming more adaptive and responsive to current events, Gudskul engendered new possibilities by connecting beyond Indonesia. As part of this unprecedented Batch, we were able to share and learn about different contexts in which collectivity persists.

Through four seminars, we introduced AAA’s extensive research on art pedagogies in relation to the development of contemporary art across Asia. After sharing case studies from China, India, the Philippines, and Thailand, we invited each collective to focus on one historical collective that most resonated. 2 Those who shared similar interests formed a group, which our researchers joined to exchange ideas, answer questions, and provide materials to inspire the collectives’ artworks. Our team crafted the exhibition narrative and display ideas only after all the works were finalized. All decisions were made in group discussions.

ÖE: The circular model of working diverges from our usual ways of organizing projects, which are often linear and entail a clear division of work. It’s refreshing. I would like to highlight an artwork here: In the middle of the library, we have a one-meter-high fire sculpture made by Quezon City–based collective Load na Dito. It is placed on top of a table covered with the reproduction of a black-and-white photograph depicting a burning action by Xiamen Dada, an art collective known for their radical performances critiquing art institutions in China in the late 1980s. This sculpture is further juxtaposed with a video documentary showing the creation of a four-meter-high effigy for a street demonstration by a group of collectives from Quezon City. Here, Load na Dito proposes the act of burning as a symbol of change and regeneration, a metaphor of collective actions that challenge institutions. By showing their connections with other collectives—both past and present—Load na Dito pays tribute to the legacy of activism of collectives and carries the torch forward.

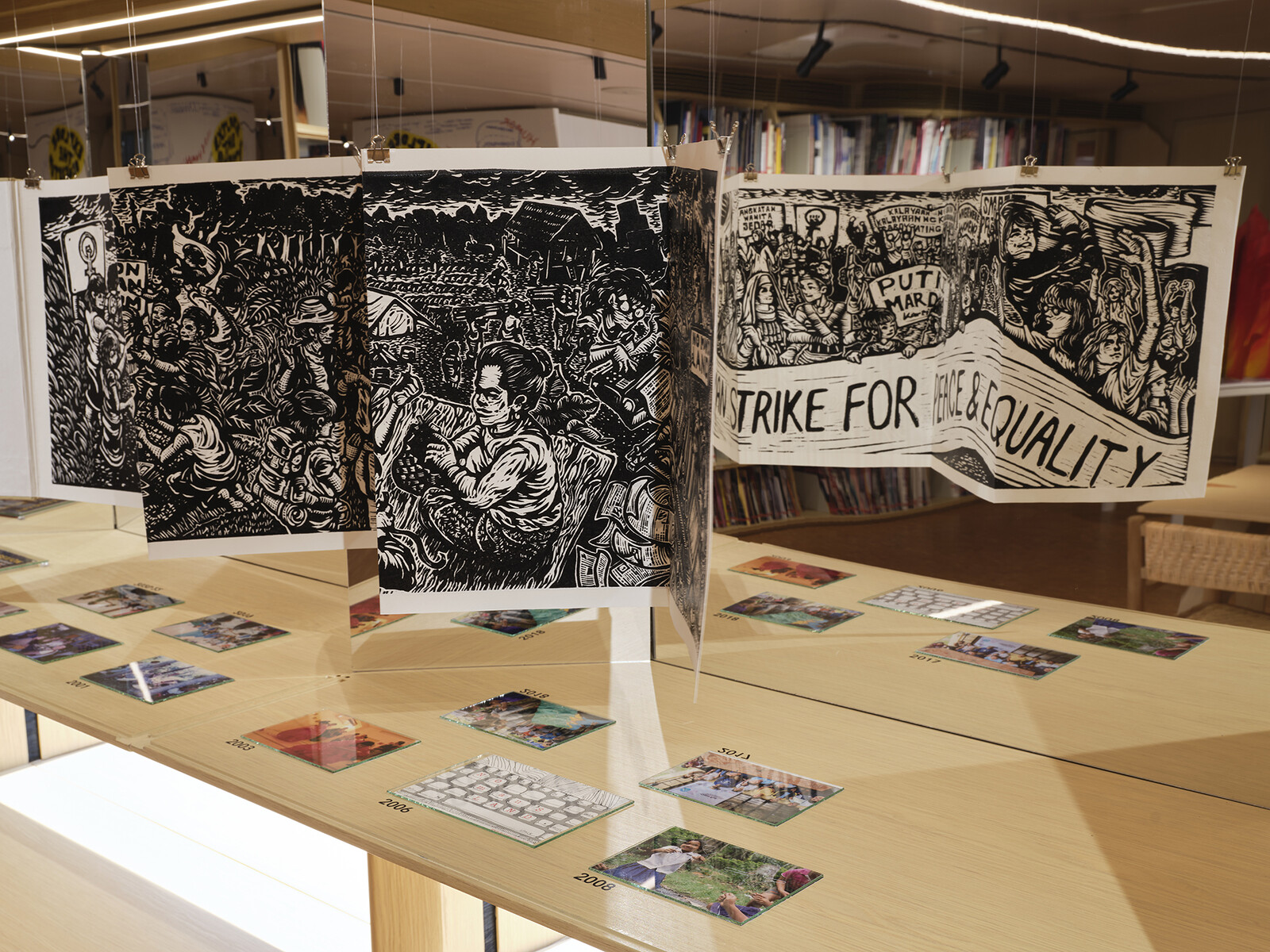

SC: Another compelling contribution is one between Pangrok Sulap and Salikhain Kolektib. They both responded to Womanifesto, a feminist art collective and biennial program in Thailand that was most active from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s.

Pangrok Sulap uses woodcut print as their medium to empower rural communities. Depicting key moments in Womanifesto’s history, their work illustrates the solidarity among women artists and local craftspeople, prompting reflections about the role of artists as custodians of traditional cultural knowledge.

Salikhain Kolektib arranges archival materials about Womanifesto and their own collective chronologically. In the spirit of collaboration, Salikhain Kolektib joined Pangrok Sulap in creating a mirror display box. The mirroring effect melds the two collectives’ works in a fascinating way: the reverse of Pangrok Sulap’s print, featuring a protest for gender equality, can only be seen through Salikhain Kolektib’s artwork. Conversely, the partial reflections of materials through angled mirror slabs disrupt the chronological timeline of the latter’s installation. Rejecting the linearity and singularity of time and place, both collectives’ works invite us to think about sustainability, adaptability, and survival—common foundational concerns of contemporary art collectives.

ÖE: It’s crucial that Gudskul, Batch 4, and our team discussed not only the potentials of working together but also the challenges and even limitations.

ba-bau AIR created an interactive jenga installation that materializes these conditions. Each hardwood block features terms from three texts related to Black Artists of Asia, a collective that initiated VIVA ExCon in the early 1990s. VIVA ExCon is the longest-running artist-led biennial in the Philippines, and this is another example of a contemporary collective revisiting art-historical documents and art actions in the region from the 1980s and 1990s.

As you begin building with the blocks, free associative readings about resilience and survival emerge. However, a jenga tower will eventually collapse, pointing to the tensions between construction and deconstruction. Yet when we think about the work not as a competition but as a cooperative game, the results become less finite. Your collective work might sometimes feel unstable, but the intention is to keep building together. Even if or when it collapses, other chances of regeneration will emerge.

SC: The fluidity of art collectives, as showcased by “The Collective School,” inspires the work we do. An archive is a mobile being, constantly rethinking its positioning and priorities through connecting with artists and collectives.

Their ideas shape our research, programs, and the sites we inhabit. “The Collective School,” for instance, has made us reflect on our long-term interest in pedagogy as a site where modern and contemporary art histories of the region have been written. Beyond the role of art school, this project has also encouraged us to generate new questions about artist-led models of education and alternative pedagogies. Apart from learning in schools, artists also learn from their peers. Collectives can serve as a continuous learning platform for those who have completed art school, as well as those who have not attended art school.

ÖE: One important takeaway from this exploration of how art collectives learn and educate is their insistence on play. It has inspired new programs, such as “Assemblage at AAA,” a durational performance by Hong Kong–based collective Floating Projects. For two days in a row, members brought in found materials as well as items from our library and office and from their own space, and began creating.

I immediately think back to a conversation with Floating Projects, where member Wong Chun-hoi said, “We should be in the same space and play together, instead of talking about what we do and how we do it.”

In the performance, the space of the archive was activated by sharing and collective action. One artist assembled a chess-like game, another few built a sculpture with shredded paper of the collective’s confidential documents, while some others made music and did automatic writing. Anyone in the library was invited to join.

SC: This collective model of learning also helped me rethink our educator programs. Since 2013, we have been organizing the annual Teaching Labs, a professional development series for teachers, each year focusing on a theme that is relevant to contemporary art and education, with this year’s being art collectives.

Working with Gudskul taught me that “art collectives” is not simply a “theme” for study but a model of learning. It inspired me to experiment with a new program, “Knowledge Kitchen,” where ten artists and ten educators gather for six hours each month to engage with creative exercises, games, chats, dinners, and sharing sessions by guest artists. We would like to use this process to practice and experiment with new models of learning. Our goal is to explore how teachers and artists can co-learn, co-create, and co-work together.

Arts programming, like formal education, often transmits knowledge one way; artists or teachers unilaterally impart their knowledge and experience to an audience. This program seeks to cultivate a more open and equal environment for knowledge exchange. We want to link artists’ unique abilities to interpret the world with educators’ intimate understanding of classroom settings. It’s exciting to see what comes out of this. Who knows? Maybe self-organized collaborative projects, lifelong friendships, and more. Our hope is that through this exploration, teachers and artists will reconsider their relationships with students and audiences in various educational and artistic settings, and engage with new imaginations for the future.

ÖE: Yes, we hope to move away from hierarchical ways of knowledge sharing. Apart from “Assemblage at AAA” and “Knowledge Kitchen,” we also hosted a live-streamed cooperative board game called “Speculative Collective.” Rather than inviting Gudskul and the eight collectives to present a talk, we asked them to show us what they cared about through playing. By responding to a series of challenge cards and drafting solutions, they revealed how they approach resource-sharing and collective decision-making. We wanted our audience to engage with—not to be told about—the exhibition.

SC: It’s important to us that this exhibition is the inaugural one of our newly renovated library. We have built a reading room in the center of the library, creating a space for co-working and co-learning, which also serves as a social space for discussion and learning from one another. Working with art collectives across Asia has not only helped us reorient the direction of our programming but has also allowed us to see the necessity and urgency of collectivity here in Hong Kong. We’ve deepened ties with our local partners Floating Projects and Rooftop Institute, whose practices revolve around alternative learning models. This is our first time studying the topic of collectives so closely, and the new library reflects who we are in the spatial sense. Since the beginning, we did not want the library to be a static collection, but rather a place to open up discussion. The study of collectives has made us realize that we share many values with Gudskul, such as learning from friends, engaging in artistic conversations, sharing knowledge, exploring the ecosystem, caring about sustainability, being speculative, and making friends, which are all essential for archive building.

A series of programs at the library resulted from organic discussions with these collectives. In particular, Hong Kong Conversations brought together different generations of artists and cultural workers to discuss historical and contemporary conditions that make collective work necessary in the city. The first talk gathered members from eight Hong Kong collectives founded in the 1990s—Southern Artists Salon, Green Wave Art, The Originals, Epical Chamber, NUX, Community Museum Project, Your Ears Covered, and Kultkuli—followed by three younger collectives—Black Window, Floating Projects, and Popo-Post Art Group. For me, it was a historical moment to see different generations of collectives in the same room, listening to and learning from each other.

ÖE: “The Collective School” is an example of how we see archives as social spaces to bring people together, to exchange knowledge, and to connect regional and local contexts. Some consider archives depositories that do not have to interpret or display their holdings. For us, artistic collaborations, including the ones developed from “The Collective School,” are crucial to challenge this view.

Our collaboration with Gudskul and eight other collectives taught me to insist on using exhibitions and programs as research as well as pedagogical tools. The project rearticulates our understanding of art history, one that prioritizes relationships and communities over individuals and singular artworks.

As part of “Assemblage at AAA,” here is an excerpt from the automatic writing of Linda Lai from Floating Projects: “A fresh new library surrounded by chaos and calm before a tempest. Free conversations absolutely free and automatic and without a frame from a handful of frames and many breakable frames.” 3 This is how I would like to imagine our library—a site for artistic intervention and knowledge via the engendering of fragments, play, and free associations, whether they are verbal, sculptural, or textual.

We are also grateful to our local Hong Kong partners Floating Projects and Rooftop Institute.

The case studies include the Stars Art Group, Xiamen Dada, and the New Measurement Group in China; Autonomous Women’s Movement in India; Black Artists of Asia in the Philippines; and Womanifesto in Thailand.

See →.