https://hdk-valand.gu.se/

Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / YouTube

In the essay “Does it ever end?,” Leonardo Custódio, an Afro-Brazilian educator and activist researcher, asks of reforming the academy, “Is this solidarity? Is this collaboration? Is it support? Charity? Are these acts to feel good about myself?” 1 Custódio’s text fell into my hands at the end of a year of exchanges on “publicness,” and though it is largely concerned with activism and academia, his essay poses questions that are also relevant to contemporary discourses on public art. “Publicness” is a conflicted term, one that refers to “a field of problems, tensions, and contradictions,” as Professor Mick Wilson said it in one such exchange, and yet the term encourages an understanding of problems and permutations inherent to contested ideas like “public art,” “the public sphere,” or “the public.” These terms themselves have undergone numerous historical shifts in meaning and carry distinct and often contradictory connotations. “Public” derives from the Latin term publicus, an adjective which referred to “belonging to the people,” an understanding that was misleading even millennia ago as a portion of Rome’s population was enslaved and thus had no right to ownership nor access to a kind of commons. Similarly, in ancient Greece, public space was reserved for free adult male citizens (dêmos), and slaves, women, and children were limited to the apolitical private realm. Today, a “general public,” one that presumably includes everybody, seems even more of a fiction than a fact. Contemporary discourses have revealed how different groups with common genders, orientations, or ethnicities, for example, are often excluded from public space and how their exclusion from and lack of representation in public art are intrinsically tied to the concept of the public itself.

At present, in public urban spaces of the Global North, representations of historical oppressors and the imperial power structures, colonial value systems, and patriarchal legacies that aided their history-making often remain the most prominent examples of public art. Such works raise questions about the processes that created them and the role of power in producing public art: Who is commemorated, granted space, and made visible? Who decides? What underlying structures determine the conditions under which public art can emerge and be perceived? To tackle these challenges, contemporary public art practices have sought to deploy democratic strategies that are characterized by collaboration, participation, and transparency, and new forms of public art have shifted away from site-specific, permanent monumental structures toward works that create publics themselves and present opportunities to engage as modes of operation. These new works are not made for but with publics and communities, an orientation of relations that Custódio probes in his essay.

Rather than answer these questions directly, the yearlong course “Commissioning and Curating Contemporary Public Art” used them as critical frames of reflection on participants’ own practices and roles in public art, whether as curator, artist, or policymaker. Delving into core concerns of the public realm, the course ruminated on curatorial and commissioning challenges in public art and proposed tools and strategies for addressing them. “Commissioning and Curating Public Art,” offered through HDK-Valand, University of Gothenburg in collaboration with Public Art Agency Sweden and the University of Arts Helsinki, is a one-year distance learning course open to participants from different backgrounds, from professionals in the arts and cultural sectors to activists and community groups, that seeks to produce knowledge and exchanges about the potential impacts of contemporary public art. For the 2022–23 edition, the lecturers guiding course discussions were the Gothenburg-based Brazilian artist Kjell Caminha, Copenhagen-based Swedish artist Kerstin Bergendal, and the Dublin- and Gothenburg-based artist, educator, and researcher Mick Wilson. Their leadership was defined by a combination of empathy, experimentation, and inspiring teaching that was supported by theory, engaged with critical discourses, and rooted in their own art practices. Throughout the year, more than twenty participants met in digital space twice a week for lectures on publicness, project presentations, and group discussions on site-specific works and exemplary public commissions. Guest lecturers, such as the artists Jason E. Bowman, Suzanne Mooney, Frida Klingberg, and Maddie Leach, joined the course to share their own work with participants. In addition to these ongoing weekly sessions, three intensives focused on public art in Northern Europe were offered in Gothenburg and Helsinki. The course curriculum also sought to develop individual participants’ research interests and related case studies, as well as the conceptualization and implementation of each participant’s practical project. Within the regular program of feedback groups and plenary discussions, students presented ideas in smaller sections, ruminating on their own intentions, roles, and interactions with the public realm. Regular written reports summarized research activities and project ideas, to which teachers provided feedback to refine, sharpen, or reevaluate decisions. Democratic and collaborative approaches were not only taught theoretically but also practiced on a methodological level, providing students space to pursue self-selected topics and a measure of control of the pedagogy by inviting guest lecturers into course discussions.

Workshop intensive in Helsinki, September 2022. Photo: Kjell Caminha.

Practical projects considered diverse publics and modes of public art. Sweden-based artist Smi Vukovic explored perspectives of the public sphere in photographic work and an essay that brought together her experiences as a teenager in Belgrade in the 1990s with a series of notes made thirty years later to reflect on how the city and its transformations have affected perceptions of public space. Curator and art producer Alexia Alexandropoulou, based in Athens, developed a case study of the INTERFERENCE light art festival in Tunis that considered how public space in Tunisia can help young artists and arts professionals pursue their practices. 2 Joeleen Lynch, a public art project manager and independent curator based in Ireland, created a toolkit for local cultural authorities producing public art programs under the Per Cent for Art scheme. 3 These and other participant projects clarified how public space and access to it are informed by local regulations, and as “Commissioning and Curating Contemporary Public Art” progressed, it became apparent how neoliberal and capitalist interests transcend national borders to create universal conditions under which public art emerges. 4

Public space has largely become a zone of consumption, which reinforces certain exclusionary factors determined by class, and public art projects that do not abide by capitalist logic, deviate from goal-oriented plans, involve participation in research and approval processes, or require longer time frames for production often are not funded. However, during our first intensive course, held in Gothenburg in April 2022, we encountered examples of public artworks and local commissioning policies that have nevertheless responded to and challenged these neoliberal conditions. On the intensive’s second day, Frida Klingberg of the Gothenburg Department of Culture unpacked the process of commissioning and implementing a new artwork commemorating the city’s queer history. The project stemmed from the idea of a multiyear preliminary review reconfigured as a series of artistic interventions that created space for experimentation, collaboration with existing communities, and cocreation with other cultural producers. 5 Unlike many common public art developments, in which preselected juries autonomously select an artist to create a work for a chosen site, Gothenburg’s Charles Felix Lindberg Fund allowed all residents to continuously propose their own ideas for artworks and sites. Instead of appointing a jury, the city’s cultural department began by exploring general questions about the nature of the artwork and researching local queer community histories through an experimental study. They collaborated with various artists, activists, and organizations and held workshops to discuss what kind of monument could be created, how it could be implemented, and where it could be placed. Between 2020 and 2022, as part of the study, a city walk, workshops, film programs, illustrations, and a poster campaign were carried out. Only then, based on insights from these activities, was a site for the monument selected and an open call formulated. In 2022, artist Conny Karlsson Lundgren received the commission to realize the monument: an abstract sculpture representing the floorplans of various historically important sites for the local queer community in Gothenburg.

Another key case study presented during the same intensive demonstrated how agency and participation can be part of a project’s conceptualization rather than only in its implementation. “PARK LEK,” by Kerstin Bergendal, was a social art project that took place from 2010 to 2014 in the Stockholm suburb of Sundbyberg, and, like the project in Gothenburg, exceeded the usual time frame for such works. 6 In 2010, the Sundbyberg city council was deliberating on a new urban development plan that would have divided an important green space in the city into several smaller sections and added more housing to an already densely populated area. Supported by Marabouparken Konsthall to realize her counterproposal, Bergendal engaged residents of all ages, local clubs and associations, and other interested parties about their perspectives on and visions for the green space. With neither permanent interventions nor major art actions on existing buildings, “PARK LEK” focused on social exchange, creating a discursive framework around the development and establishing time to listen to community input. After an initial phase of open exchange, workshops and discussions were held on-site and, with the help of planners and architects, reviews of the proposals’ feasibility for the district were undertaken. The artist translated the results of these meetings into a new development plan for the neighborhood that, as a reworking of the design proposed by city officials, represented the needs of residents, the people who would ultimately be effected by the development. By creating this new plan, one rooted in dialogue and person-to-person exchange, the project translated residents’ perspectives into a language that could be understood by those in positions of authority. Without Bergendal’s counterproposal, the city’s urban development plan would have been implemented without further citizen participation and residents’ interests would have been subordinated to the need for new housing, which could be built elsewhere in Sundbyberg. The project hosted many small conversations, negotiated opposing opinions, and finally compiled a concrete collection of needs and solutions. The democratic processes that defined “PARK LEK” expanded on municipal control of public space by bringing the city’s population into direct contact with the bureaucracy of administering Sundbyberg. Inspired by these experimental approaches and aware of the deficiencies of existing funding programs, which shy away from projects that challenge the status quo of public art production, course participants brainstormed with Bergendal a new vocabulary that could communicate alternative public-art commissioning practices. Terms such as “prototype,” “strategic question,” “friction as fertilizer,” and “operating space” entered course conversation, and participants related to our own roles “witnesses,” “catalysts,” “offer-makers,” and “frame-setters.”

These experimental and intuitive notions were underpinned by inputs on proposal writing and the concept of the case study in theory blocks with Mick Wilson. Especially during the first semester, the theoretical units “Deconstructing Public Art” and “Vocabularies of Public Art” created a productive space for contextualizing what we participants observed in ourselves and the presented projects. In one unit, in addition to the implementation and problematization of the term “publicness,” we discussed German philosopher Jürgen Habermas’s concept of “public sphere” in more concrete terms. The Habermasian “public sphere” is understood as an area of social life in which individuals “publish”—make public—their opinions and thereby influence political and social discourses. 7 As a critical response to Habermas’s concept, the terms “counter-public sphere” and “counter public” emerged as feminist, anti-racist, queer, and postcolonial revisions that address the real inequalities and exclusions that structure social relations. In her critique of Habermas, feminist philosopher Nancy Fraser proposes the creation of so-called “subaltern counter publics” that provide marginalized groups such as “women, workers, people of color, and gays and lesbians” with space to meet, discuss, and create their own parallel counter-discourses. 8 Complementing Fraser’s concept, Doreen Massey, a British geographer and social scientist, explains that when “we [take] space seriously as a dimension that we create through our relations which are all full of power and as a dimension which presents us with the multiplicity of the world and refuse to align them all into one story of developments, then we really re-imagine the world in a different way, it presents us with different political questions, I think it opens up our minds.” 9 The formation of such counter-publics thus politicizes as the opposition those who are not represented among the dominant forces. As an example of such counter-discursive creations, Fraser refers to the invention of new terms such as “sexism,” “double shift,” or “marital, date, and acquaintance rape” as a powerful strategy for interjecting subjective realities and discourses into the dominant, preexisting ones without having to actively participate in them.

Following Fraser’s comments, the aspect of language and the creation of new and different discourses are interesting concepts within publicness. The mainstream interpretation of the public sphere as a democratic space suggests that people encounter different languages and different worldviews conveyed therein. The white, cis-hetero hegemonic character of public space that Fraser and others criticize, in turn, leads to the dominance of certain groups, discourses, and languages over others, making participation more difficult for those who do not speak them. Some languages—and here I refer not only to official national languages or dialects and sociolects but also to code systems in general—are the result of oppression: consider the idioms imposed on formerly colonized peoples or the expansive bureaucracy that regulates and limits access to resources like social welfare, which can only be received if one has an identity card and, consequently, a permanent legal residence. On a different scale, these regulating systems are also visible in the art world, where every public project requires a formal proposal, and where historical events are only considered important if expressed through the ever-same sculptural monumental aesthetic.

Pekka Kauhanen, National Memorial to the Winter War, 2017, during the public monuments tour with guest artist and lecturer Suzanne Mooney for the workshop intensive in Helsinki, September 2022. Photo: Kjell Caminha.

Within this hierarchical world, with its dominant way of speaking, it can be difficult to create languages of one’s own. This became clear during the second intensive course in Finland, where we discovered public artworks in Helsinki together with guest lecturer Suzanne Mooney and Kjell Caminha. The historical power relations mediated in Helsinki’s public space became visible at the start of the tour, when we learned more about the city’s oldest monument, The Stone of The Empress, a red granite obelisk by German architect Carl Ludvig Engel depicting the two-headed eagle of Russia. Erected in 1835, when Finland was under Russian occupation, Engel’s monument honors and commemorates the visit of Empress Alexandra of Russia to the city. Nearly two centuries later, in 2017, the Finnish artist Pekka Kauhanen erected a new sculpture in Helsinki’s public space, different in material and technique but similar in principle, of a figure standing on a globe, oversized and eternal like Engel’s. In contrast to the earlier monument, however, Kauhanen’s work was made to commemorate the Winter War of 1939, in which Finland fought against re-invasion by the Soviet Union. Although the two monuments were commissioned under different circumstances and respond to different political contexts, they use a similar language, that of the monumental public sculpture intended to endure the tests of time. What do concepts of language and discourse tell us about the public sphere? The discussion in the course was not only about problematizing the public sphere but also how such problems can be raised and contested, especially through the means of public art. Different, marginalized languages or systems, when cultivated, can manifest the diversity inherent in public space and, when communicated through art forms and practices, can trigger processes to address the exclusions and deficiencies of the public realm. The repetition of preexisting aesthetic codes and systems in public art, like Kauhanen’s retread of Engel’s work, perpetuates the power relations associated with them. However, any language can be learned, translated, and appropriated, as Fraser suggests with her strategy of “inventing new terms” and as the projects presented in the course demonstrated by expanding or reinterpreting existing practices like the preliminary study. Artistic or activist methods can be used to initiate precisely these appropriations, to mediate between different systems, to expand or question the existing ones, and to create safe spaces for “counter publics.”

Carl Ludvig Engel, The Stone of the Empress, 1835, Helsinki. Via Wikimedia Commons: Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

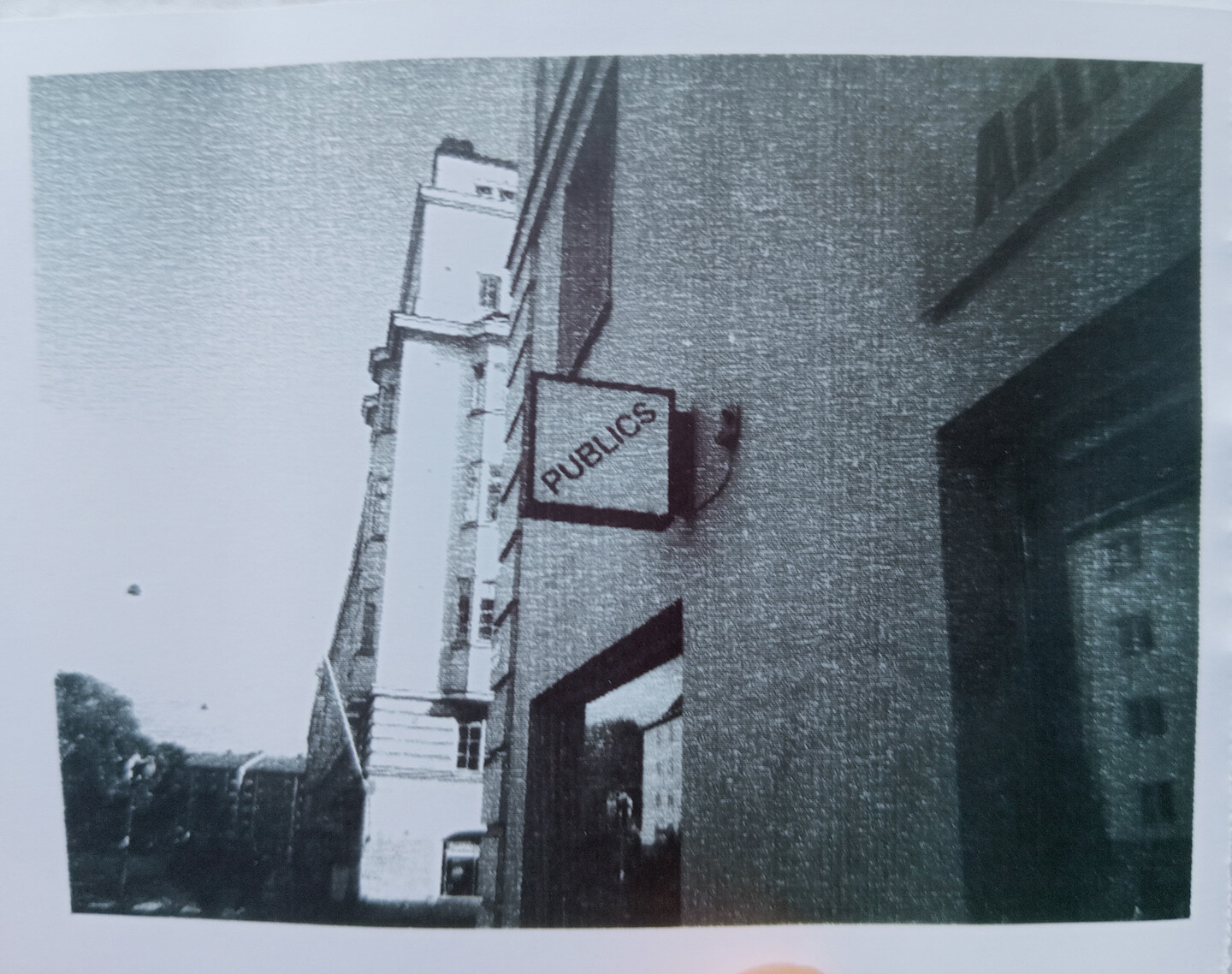

Continuing our intensive in Helsinki, we visited two such spaces for art that do not intervene in the already existing public sphere but build their own infrastructures and invite the public to engage in new alternative frameworks. The curatorial agency PUBLICS is a multifaceted space in Vallila, a predominantly residential neighborhood in the central-northern part of the city, led by Paul O’Neill as artistic director and Eliisa Suvanto as program manager. 10 Many more collaborators, artists, curators and creatives, such as the annually rotating representatives of the “Public Youth” group, art historian Pilvi Kalhama, project manager and curator Adelaide Bannerman, and curator Bassam El Baroni, have shaped the space’s programming and its mission as a platform for learning, discussion, and critical and collaborative engagement with contemporary art and publicness. According to its website, PUBLICS proposes an understanding of publicness “as always plural—as a concept; as a group of people (imagined, actualized or real); and as a contested spatio-temporal location/discourse in the world.” 11 To fulfill this goal, PUBLICS offers a public library, lectures, events and performances, opportunities for youth to get involved in a special advisory board, and “parahosting,” in which PUBLICS shares its space and infrastructure with other organizations to run their own projects that align with PUBLICS’ mission.

Like PUBLICS, the Museum of Impossible Forms (MIF), led by artistic director Giovanna Esposito Yussif, is in a neighborhood that is still largely excluded from Helsinki’s art infrastructure, Kontula, an eastern district of Helsinki, which was developed in the 1960s and 1970s and gained a notorious reputation for violence and drug trafficking. 12 In a space in a neighborhood shopping center, MIF hosts a library, archive, exhibitions, and a rotating curatorial program, and its website features performances, lectures, workshops, yoga, dance sessions, and more, thereby extending its services to communities outside of the neighborhood and Helsinki’s art scene. MIF describes itself as a counter- or para-museum, implying its position as a counter-offer to established and well-funded institutions, which do not often serve people who live in places like Kontula. And unlike most larger institutions, MIF’s fundamentally inclusive and diverse goals are to “fill gaps in the critical artistic practice and pedagogy for BIPOC artists in Helsinki” and “to engage with experimental, marginal, and migrant forms of expression.” 13 By rooting itself in a place outside of conventional art networks and publics, MIF has created a new space in which like-minded creatives can build communities free from predetermined outcomes and the pressures that established institutions constantly impose on creative professionals. Like the course itself, PUBLICS and MIF challenge the predominant understanding of public art as something limited to sculptures in public spaces. Rather, these organizations create structures that not only talk about the public but produce it themselves. The potential diversity and accessibility for different communities is already evident in the fact that their strategies are not based on a single person who selects individual objects for exhibition but instead on processes and collaborative work that shapes the organizations’ own structures.

Course visit to PUBLICS during the workshop intensive in Helsinki, September 2022. Photo: Kjell Caminha.

Creating such experimental structures and strategies—counterproposals to dominant forms of public art—entails recognizing that these new forms are necessary to harmonize the real public sphere with its ideal as a diverse and democratic space. Visits to organizations like PUBLICS and MIF, as well as participants’ reflections on their own practices, initiated this realization though interweaving theory and praxis. Throughout the course, in online meetings and in-person intensives, we participants were asked by our teachers to reflect on “To what and to whom are you accountable in your current role?”; “What values and principles should inform public commissioning?”; and “What forms of instrumentalization affect your current role? How can you be more instrumental?” This critical questioning and the translation of its answers into concrete projects—from proposal to the work being made public—can be enormously challenging. However, this process of questioning, reflecting, and adapting allows input from others and involves critical feedback into the development of public art projects, often from the public those projects are intended to engage.

What “Commissioning and Curating Contemporary Public Art” taught on a methodological level was also conveyed in practice: process-oriented and decelerated strategies that continually incorporated new insights and inputs as counter-models to the conventions of public art and that favored smaller, diverse interventions over grand gestures. The course pedagogy created infrastructures, spaces, and frames that could be collaboratively equipped and appropriated by participants themselves. Thus, by learning modes of operation that demonstrate the importance of trial and error, experimentation, and prototyping to democratic and collaborative practices of the public, we participants could test out strategies that circumvent prefabricated and “universal” solutions for producing art in the public realm. The challenge of such strategies, of course, is to communicate them to bureaucratic funding systems in such a way so that they do not fall through funding schemes. However, the projects and the curatorial and commissioning approaches developed by course leaders, guests, and participants productively bridged the gap between creative practice in and with publics and administrative exigencies. Laying the groundwork for contemporary public art that not only creates counter-forms to accepted practices but also integrates itself into actually-existing systems, the course provided students the critical and practical tools to productively react to and augment dominant forms of art and knowledge production.

Leonardo Custódio, “Does it ever end? A (Self-)reflection about collaboration between academia and activism,” in How to Work Together—Seeking Models of Solidarity and Alliance, eds. Emily Aiava and Raine Aiava (Helsinki: Museum of Impossible Forms, 2020), 186.

Alexandropoulou was a member of the jury for the festival’s YOUNG MASTER POGRAM 2022. See →.

The Per Cent for Art scheme is a widely adopted program in which a minimum of 1% of the construction budget of a new public building or infrastructure project is set aside to commission public artworks. The purpose of these programs is to integrate works of art into the built environment, making art accessible to the public and enriching the local community. In the early 1930s, Finland became the first country to adopt such a program as official government policy, and many other European countries and jurisdictions in the United States have implemented the program in the subsequent decades.

Mel Jordan and Doreen Massey elaborate on such conditions and relations. See Mel Jordan, “We are all everyday superheros,” Art and the Public Sphere 1, no. 3 (December 2011): 239–41, and Doreen Massey, “Doreen Massey on Space,” interview by Nigel Warburton, January 2013 →.

The initiative to create an artwork that would make the history of the local LGBTQIA+ community visible came from the Gothenburg LGBTQ Council in 2018, which applied through the local Charles Felix Lindberg Endowment Fund.

See →.

Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. Thomas Burger with Frederick Lawrence (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989).

Nancy Fraser, “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy,” Social Text no. 25/26 (1990): 56–80.

Massey, “Doreen Massey on Space.”

PUBLICS describes itself as “a curatorial agency with a dedicated library, event space and reading room in Vallila Helsinki, known for its industrial working class histories and, more recently, for its influx of divergent artistic and academic communities.” See →.

See →.

See MIF’s website →.

MIF’s website.