https://ifa.nyu.edu/

Instagram / Facebook / Twitter / LinkedIn

1. Why did you decide to go into teaching?

I treat with suspicion one’s ability to narrate honestly the multiply determined and somewhat alchemical sequence of one’s own life; certainly, the major topographic features of my own seem more the results of unbidden tectonic shifts than anything resembling “decisions.” We could say teaching offered the money I needed, or that my mother was a public school teacher for much of her life. Such are the novelistic causalities of circumstance or inheritance, but teaching was probably at once more fundamental and contingent than even these.

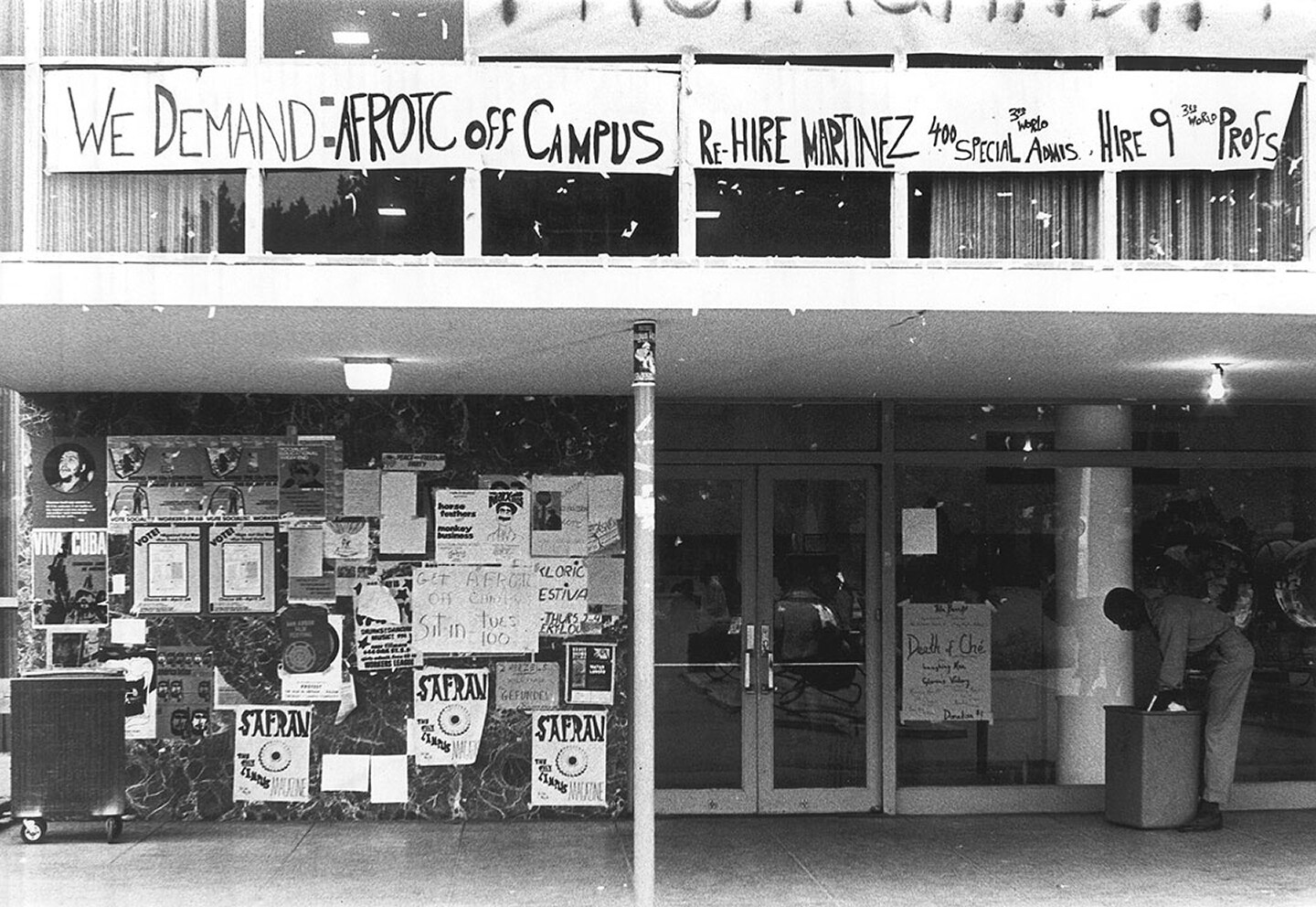

I fell into it accidentally; I love it embarrassingly. Both are true. Resistant to the pretty fiction of the individual, I would also highlight that my position in universities, precarious as it is, is above all the consequence of political work done decades before my time. The Third World Liberation Front strikes of 1968, at San Francisco State University and the University of California, Berkeley, saw students demand ethnic studies courses as part of a larger political program. At Wesleyan University, where I previously taught, students occupied a campus building, Fisk Hall, on February 21, 1969, demanding support for its Black students, faculty, and staff. On May 22, 1970, San Diego State College became the first higher-education institution in the nation with a women’s studies program, the result of the Ad Hoc Committee for Women’s Studies, which had offered an initial group of classes—sans administrative permission—in January of 1970. These are only a few episodes from a larger history that has directly produced the conditions that enable me to teach.

2. What drew you to your school and what is your teaching philosophy?

The Institute of Fine Arts at New York University is a unique place. Though I offer one course a year to NYU undergraduates through the core curriculum, the IFA itself is dedicated solely to graduate education; I relished the opportunity to work more extensively with master’s and doctoral students and to have a hand in shaping the field. In addition to being bright and dedicated, our students often already work (or have worked) at major museums, galleries, publications, and nonprofits across the globe. Their desire to expand their art historical knowledge in relation to their real-time positions in such institutions impresses me greatly, and the speed with which the ideas they explore in the classroom inflect their conversations and decision-making elsewhere makes the stakes of our conversations clear.

My students are fantastic, but I could not have known quite how great they would be before I began, so it was really the contours of the position itself that so appealed. My official job title is “Linda Nochlin Visiting Assistant Professor of Art History,” a new professorship created thanks to the generous support of Valeria Napoleone and championed by the IFA’s current director, Christine Poggi. I hope it does not sound overly obsequious to say that it was Nochlin’s name—and with it, the explicit remit to teach feminist art history—that seemed almost unfathomably idyllic.

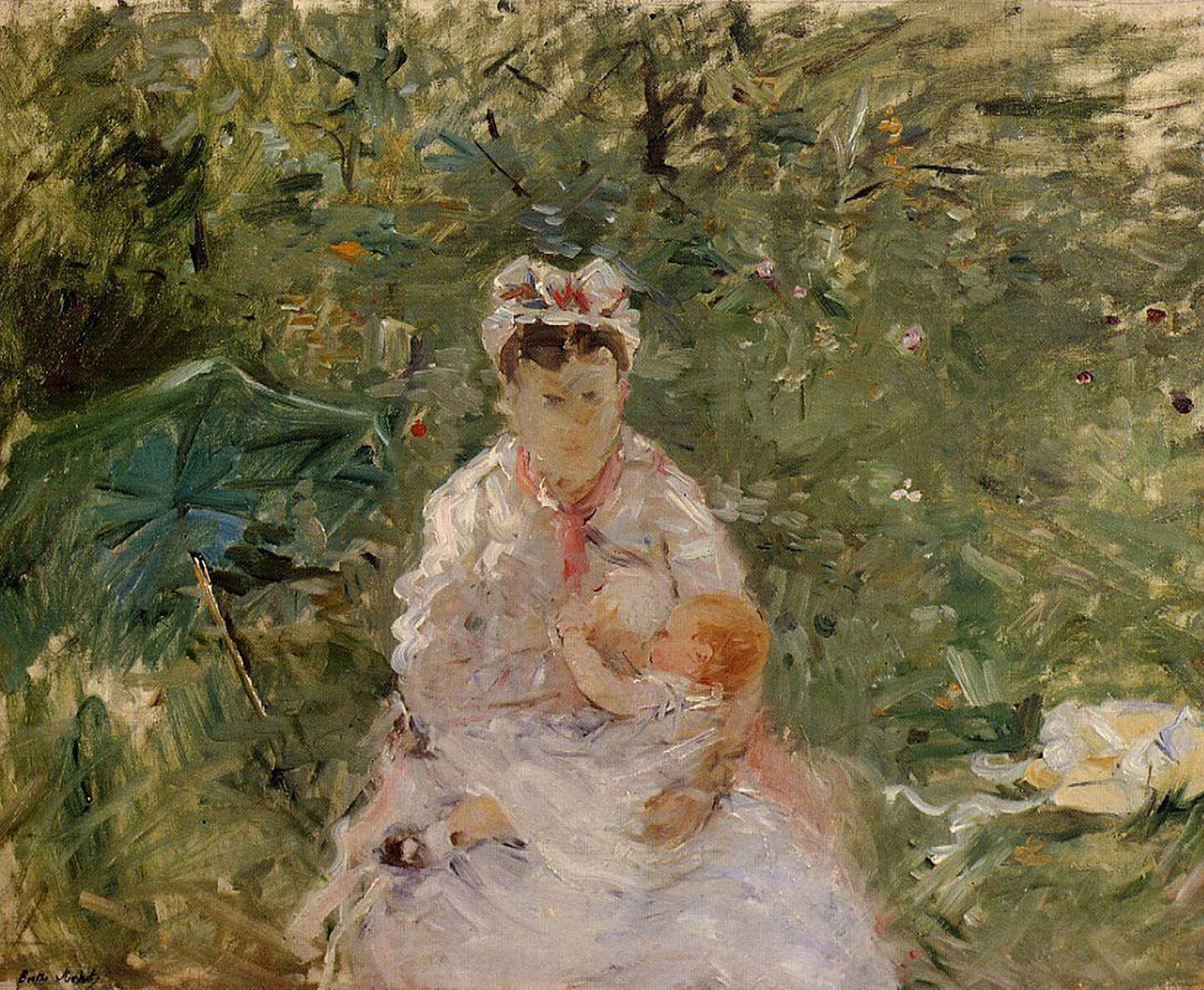

Nochlin’s effect on the discipline of art history is legion, and the recognition of her signal 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” is far from unfounded. Whenever I teach it, I’m newly awed by it, not least for the ways it makes room for analyses that are not explicitly present in the text itself. It emphasizes the institutions that any individual is by necessity extruded through, and so we can use it as a model to ask new, different questions about gender’s intersections with race and disability, for example. Above all, I admire how Nochlin’s work approaches the question of inequity not by attempting to recuperate a given artist, genre, or operation according to the extant terms but rather queries the terms themselves. This is the primary lesson I am always trying to impart to students: hierarchies of value are themselves entangled with and shaped by ascriptive categories of gender, sexuality, race, and ability. That essay is by far her best known, but there are so many other writings of Nochlin’s that shaped me profoundly: Tucked into “The Imaginary Orient” (1983), her analysis of orientalism in French academic painting in the nineteenth century, is an assertion that art history is and should be a deconstructive or critical discipline, not a positive one. 1 “Morisot’s Wet Nurse” (1988) blew my young mind. Encountering it after the more canonic essay of 1971, I was stunned by how Nochlin revealed in Berthe Morisot’s maternal imagery—which by then seemed familiar or even somewhat boring to me—not a “mother” but a “seconde mère,” not “natural” nurturing instinct but embodied labor sold in exchange for wages, not just marginalization on the basis of gender but the deluxe privileges of class, and not only Morisot’s precarious purchase on the “canon” but the unnamed others on whom her artistic labors obliquely but absolutely relied. So too did I come to understand, through Nochlin’s close analysis of a painting that is, quite literally, difficult to look at, how the works of art that most compel as objects of study are always those that are “fluid, unclassifiable, and contradiction-laden.” 2

Berthe Morisot, The Wet Nurse Angele Feeding Julie Manet, 1880. Private collection, Washington, D.C.

3. What theory and art history do you consider most essential for your students? What artist or artwork do you refer to most often?

This phrase is cribbed from a source now entirely lost to me, apologies, but on the first day of class I often tell students that my sole ambition is to deepen the quality of their attention. That’s it. Precision is always the order of the day. Students know I love experimentation but abhor sloppiness and vague generalization. To my own discomfort, I champion rigor, but cautiously so—not as entreaty to some abstract and elitist ideal but rather because I believe that carefulness and specificity are the very things that the most marginalized subjects are so frequently denied. I advocate a method of art historical inquiry that begins by acknowledging that systems of gender and processes of racialization are never only exclusionary but also always already extractive. So the task is not merely additive (“diversifying the canon”) but to renovate our questions, and to see how ostensibly “excluded” subjects were, in fact, often there, but subordinated by unequal social arrangements. Fluency in the granular details of history, with all its contingencies and aporias, is indispensable.

Deepening the quality of my students’ attention means initiating them (or strengthening their skills) in the stalwarts of art history: close looking and formal analysis. We collectively annotate images and discuss facture at length. Yet at some point in the semester, I often read aloud an excerpt of Toni Morrison’s essay “Black Matters” from Playing in the Dark. In it, Morrison analogizes reading American literature to “looking at a fishbowl.” First, she demonstrates her ekphrastic mastery (“the glide and flick of the golden scales, the green tip, the bolt of white careening back from the gills”), but the passage’s magic is in its revelation: “Suddenly I saw the bowl, the structure that transparently (and invisibly) permits the ordered life it contains to exist.” 3 Close looking, I tell my students, is not simply about identifying linear perspective or its absence, or finding the strong diagonal, the warm source of light. It also means attuning one’s gaze to what might not be wholly observable: the transparent structure shaping the work’s conditions of possibility; in short, its fishbowl.

Above all, I try to teach students the very thing I find most difficult in my own research: that mediating from the cultural to the political is no simple task. Entrenched structures of power rarely straightforwardly determine artistic production; conversely, artworks are neither merely illustrative of preexisting theoretical concepts nor tidy responses to social problems alone. Yet the objects, histories, and theoretical paradigms they study can give form to these entanglements, and the intellectual work—which we can only ever undertake together—can likewise be transformative in this very way.

4. How do you navigate generational or cultural differences between you and your students?

Being among other people always entails a degree of unknowing, but we should probably acknowledge that such navigation is significantly easier from the professorial end. Differences are inexorable; relations of power sharpen their edges, and that’s how we get snagged. The power that faculty hold feels thin—barely like power at all when it is gauzily in your hands—but when you are the one it is wielded upon, it both feels and is insurmountable. Students genuinely want to do well, but they also know, somewhere, that in exchange for money they will be evaluated according to a system that has a not insignificant, if not totalizing, bearing on the material outcomes of their lives. It seems to me a shame that the utopian vision of formal education—I create conditions that facilitate a given student coming to new insights, or acquiring particular specialized skills, through a heuristic and dialectical process of their attempt and my feedback, on repeat—is so connected to credentialing and grading, in which the professor de facto functions as little more than a menial pre-screener, sorting and categorizing the “workforce” for future employers.

The classroom is inevitably also a site of transference and counter-transference. Academics do not like to admit that students occasionally hurt our feelings; students, in turn, may be unaware that the set of baroque rules they encounter, say, on a syllabus, are often little more than a (usually futile) defense mechanism, an attempt to bulwark against having one’s time, labor, or expertise disrespected. I am hardly immune to this, and my courses have their jangly little procedures too, but we academics would do better to concede that these are just ghostly outlines of a plea for reciprocity and that inevitably boundaries might be trespassed and aspirations unmet (the paper is not turned in, the instructions are forgotten, the appointment is ghosted, the thoughtfully assembled readings are ignored). It is incumbent on faculty to do whatever inner work is necessary to function more like analysts (it’s not “about” you at all) and, more importantly, to refuse, always, to give in to what my partner wisely calls “the transitive property of hurt feelings” (“I am wounded, therefore you must be punished”). It’s hard. I try to remember that when we are disappointed, it is only possible because we were first attached.

That was the counter-, now for the transference: For me, being gendered, racialized (and whatever else), in the particular way that I am, my physical presence is still something of an anomaly whether behind the tank-style desk in office hours or at the lectern, especially in a discipline like art history. The professorial mantle of authority, which some wear with ease, on me only ever looks, at least in the mirror, like an ill-fitting costume. I try not to presume, but I imagine that for some of my students, it is tempting to map their own feelings of unbelonging onto the misshapen outline they encounter: perhaps the shaggy path I’ve cut to be here can provide the map for their own. Those desires are not insignificant and are to be taken seriously, but they are, of course, structurally impossible to sate. My own run in just the opposite direction: I’d like to be both a perfectly smooth vessel and the soothing liquid within it, but I’m not; I’m just a person, with all my own inadequacies and prickliness. On this, I try to remember that disenchantment is part of learning too (cf. Winnicott’s “good enough mother”).

5. What changes would you like to see in art education?

Our teaching conditions are our students’ learning conditions and both have been subject to increasing immiseration. We need solidarity between faculty at all levels; students, both employed by the university and “consumers” of it; and above all, the workers who clean the bathrooms, take out the trash, serve the food, keep the lights and wireless internet on, answer the frenzied emails, or put out the fires both literal and imagined.

Here is a modest proposal: The price of higher education, like healthcare and housing, is set neatly at zero. Departments and schools, especially in the arts and humanities, are robustly funded, and the odious tidal wave of casualization (adjunctification and otherwise) is reversed: universities prioritize full-time, tenure-track scholars and practitioners, who have both the time to pursue their own work and, crucially, the possibility of a future in which to invest and fight. Faculty have intimate class sizes that permit one-on-one collaboration with students, the only way that learning truly takes place. Both inside and outside the university, people are well-rested and cared for; there is room to breathe, to experiment, to noodle around, to pursue projects that have no clear tether to either remuneration or anything like “career advancement.” The work of social reproduction—feeding, clothing, housing, cleaning, tending to wounds both physical and not—is evenly distributed, and because people are not subject to organized abandonment, left clawing their way to survival, we see the concomitant withering away of a culture industry dominated by the ugliest corporate pablum, tedious online infighting, attempts to resolve material contradictions symbolically, haughty meanness, hostile architecture, imperialism, petrostates, prisons, and the police. Culture gets better and weirder; everywhere there are more trees, more genders. Education is different, but so is everything.

6. What is your educational background? Did you arrive at art from another field?

I attended K–12 public school in a red state and then a somewhat religiously inflected liberal arts college, selected primarily for two virtues: its offer of an enormous tuition scholarship and its location in a big coastal city—that is, being the vehicle by which a seventeen-year-old could reasonably get out of Dodge. I was not especially academically minded then. I have made money other ways (laundering towels, wiping down exercise equipment, answering phones, entering data, “hospitality,” making copies, making coffee), but in the sense this question probably intends, I have basically only ever done this.

7. How have recent cultural movements and activism informed your curriculum?

Shimmering behind this question are events of the last five to ten years, but the word “recent” here is itself a mirage. The projects of feminist liberation, queer liberation, anti-colonial liberation, sundry plots against the chokeholds of capital, climate disaster, and the reapers we can only gesture toward with names like “misogyny,” “racism,” “ableism,” and “transphobia” are hardly new. People have been fighting repellant conditions like hell and taking care of one another for a long time, by which I mean centuries. This of course informs the curricula but not only that.

8. How much structure or independence do students have in your courses?

I’m so tickled by an imagined respondent who here admits to being either a tyrannical despot or so blurrily checked out they hardly know what’s going on. I like structure. Autodidacticism has plenty of virtues, but given the price tag on tuition, it’s simply not the genre within which we’re operating. Moreover, I believe that because evaluation is always to some degree subjective, it’s kinder to articulate to students as clearly as possible what one expects from a certain category of assignment or endeavor, and I’m committed to revealing what sociologists call “the hidden curriculum” as a matter of equity. But the students can and should always invent their own questions and pursue their particular interests, their objects of study, and above all, their stakes. If you may work on basically anything you’d like, then you’ve got to get very clear on why you chose this.

9. How does the program connect students to the surrounding art scene? How do they learn outside the classroom?

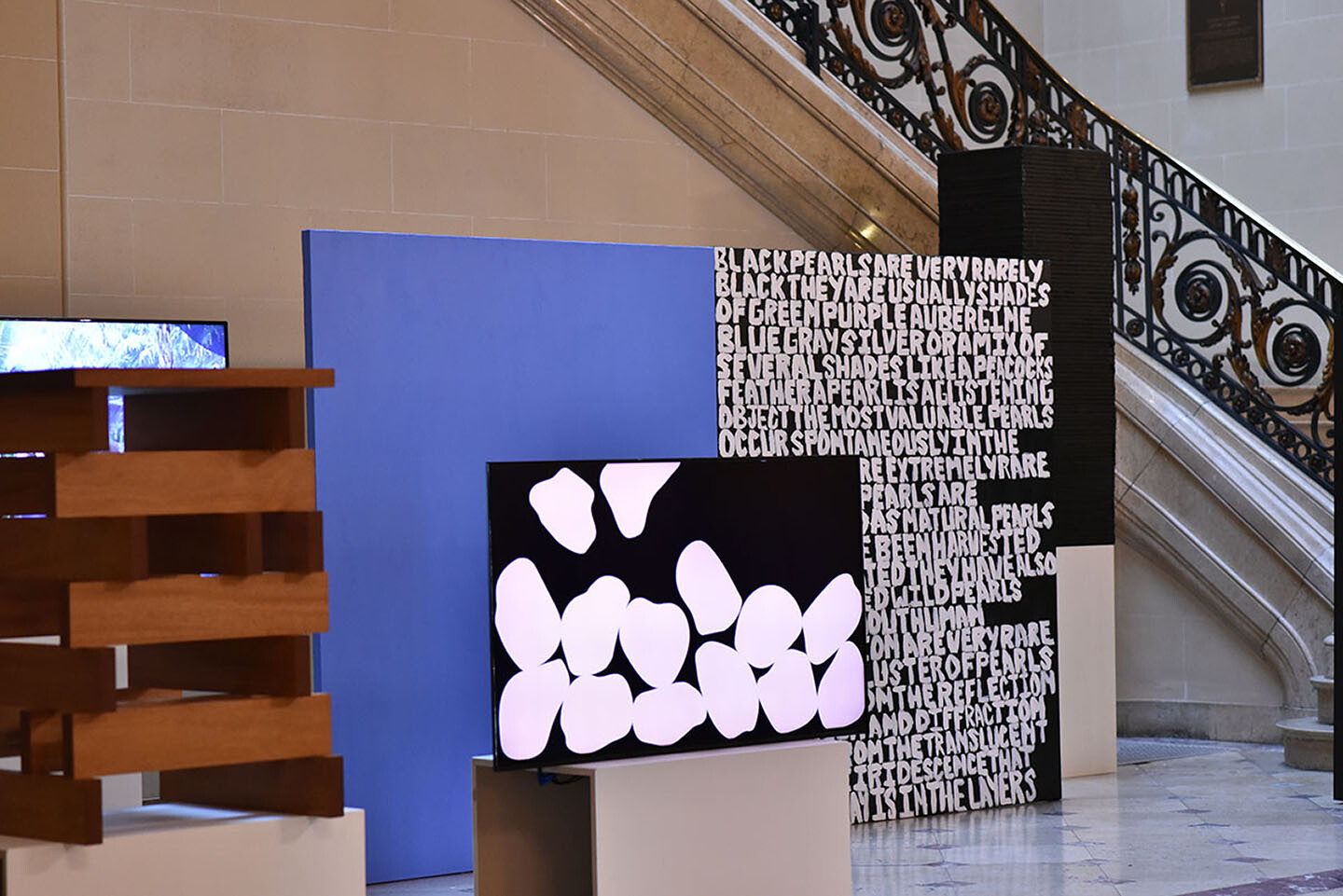

These are two distinct questions! With regards to the surrounding art scene my students are often not only connected to it but actively shaping it through their jobs, internships, and independent artistic and curatorial projects. We’ve got an embarrassment of riches in New York, it’s almost more difficult not to be overwhelmed, always missing something you wanted to see. I also feel incredibly fortunate to work for an institution that has the funds to bring in other voices. My two graduate seminars this fall, on feminist approaches to “labor” and “internationalism” respectively, were gobsmackingly lucky to have visits from: Oluremi C. Onabanjo, who gave a brilliant talk on her recent Marilyn Nance: Last Days in Lagos (2022), a scholarly act of love and a model of truly caring for an artist, as well as an object lesson in what the “photobook” can be as both a curatorial project and a pedagogical offering. Artist and filmmaker Tiffany Sia screened her film What Rules the Invisible (2022), which had just premiered at the New York Film Festival, and candidly discussed working within and against audiences’ hunger for access, the travelogue’s voyeurism, ghost stories, and making art under an authoritarian eye. Thomas (T.) Jean Lax gave us a tour of their much-lauded exhibition “Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces,” still on view at MoMA, where we got to look closely at objects and their sightlines and talked about the intensely physical feminist labors of birthing anything: an exhibition, a life, ongoing relationships with both artists and institutions. At the IFA I am also now the faculty advisor for an annual student-led curatorial project, aimed at supporting underrecognized feminist artists, and to that group the lovely Danielle A. Jackson gave a tour of her recent exhibition at Artists Space, “Las Nietas de Nonó: Posibles Escenarios, Vol. 1 LNN,” and thoughtfully discussed the practical elements of developing and hanging a show, as well as the ethic of working with artists in a way that avoids shoving them into narrow containers of immediate, reductive “interpretation.”

How do they learn outside the classroom? I hope by talking to artists and seeing shows, going out dancing with their friends, spending time with people who have no bearing on the “art world,” breaking bread with elders and kin (biological and not), hanging in boroughs other than Manhattan and Brooklyn, and going to the movies, since we live in a great era of repertory cinema here in the city. Some of my students and advisees joined me in the “optional final project” of writing and sending holiday cards to queer incarcerated pen pals via Black & Pink this winter—a modest gesture, but one that gets at what I’m most invested in “outside the classroom.”

10. What advice do you give to your students as they leave school and enter the field?

The genre of advice for entrée into the “real world” invites insularity and prioritizes “career.” The world is always already real.

Linda Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” Art in America 70, no. 5 (May 1983): 189.

Linda Nochlin, “Morisot’s Wet Nurse: The Construction of Work and Leisure in Impressionist Painting,” in Women Art, and Power and Other Essays (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 54.

Toni Morrison, “Black Matters,” in Playing in the Dark: Whiteness in the Literary Imagination (New York: Vintage, 1993), 17.