Bor is a small mining city in eastern Serbia, 243 kilometers from the country’s capital, Belgrade. It is, as the crow flies, 6,340 kilometers from the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, 4,030 kilometers from Lake Balkhash in Kazakhstan, and 8,323 kilometers from Shanghai. Bor, Addis Ababa, Lake Balkhash, Shanghai: four localities disparate in culture and geography yet connected by an atmospheric condition, the oppressive smog of reindustrialization and natural-resource extraction. Peering through this soot, in Bor I witnessed a curatorial inquiry that brought these places into affective proximity, a shared space in which the divisive logic of extractive capitalism was reoriented so that new transnational solidarities could emerge. The inquiry accomplished this by jettisoning normative conceptions of art and aesthetic production as well as the hierarchies that often limit the definition of cultural work. In doing so, it made tangible how art can establish new spaces for thinking outside of hegemonic ideas and practices and, indeed, propose new ways of imagining together possible futures that exceed the forces of epistemic and economic colonialism.

Between September 15 and 19, 2022, a range of cultural workers and Bor locals gathered for Bor Encounters, the first public-facing event of the long-term curatorial project and research inquiry “As you go… roads under your feet, towards the new future,” an initiative supported by the curatorial platform What Could/Should Curating Do? (WCSCD). Launched in 2019 by the independent curator Biljana Ćirić to find different ways for curators to produce knowledges, “As you go…” took as its primary point of departure the socio-ecological wounds wrought by the Belt and Road Initiative, a semi-global infrastructure development strategy launched by the Chinese government in 2013 as a way to expand its political and economic influence. 1 Rather than pursue a reactionary response to this neocolonial program, “As you go…” reconfigured the Belt and Road Initiative as an opportunity to explore how aesthetic and social practices of everyday life in some of the areas impacted by the development scheme might align and thus allow for moments of togetherness. For Ćirić and the inquiry’s participants, these moments permitted the sharing of situated knowledges across geographic borders, and these exchanges in turn sought to create new transnational solidarities resistant to neocolonial enterprise, which so often destroys local social life and ecologies for economic gain.

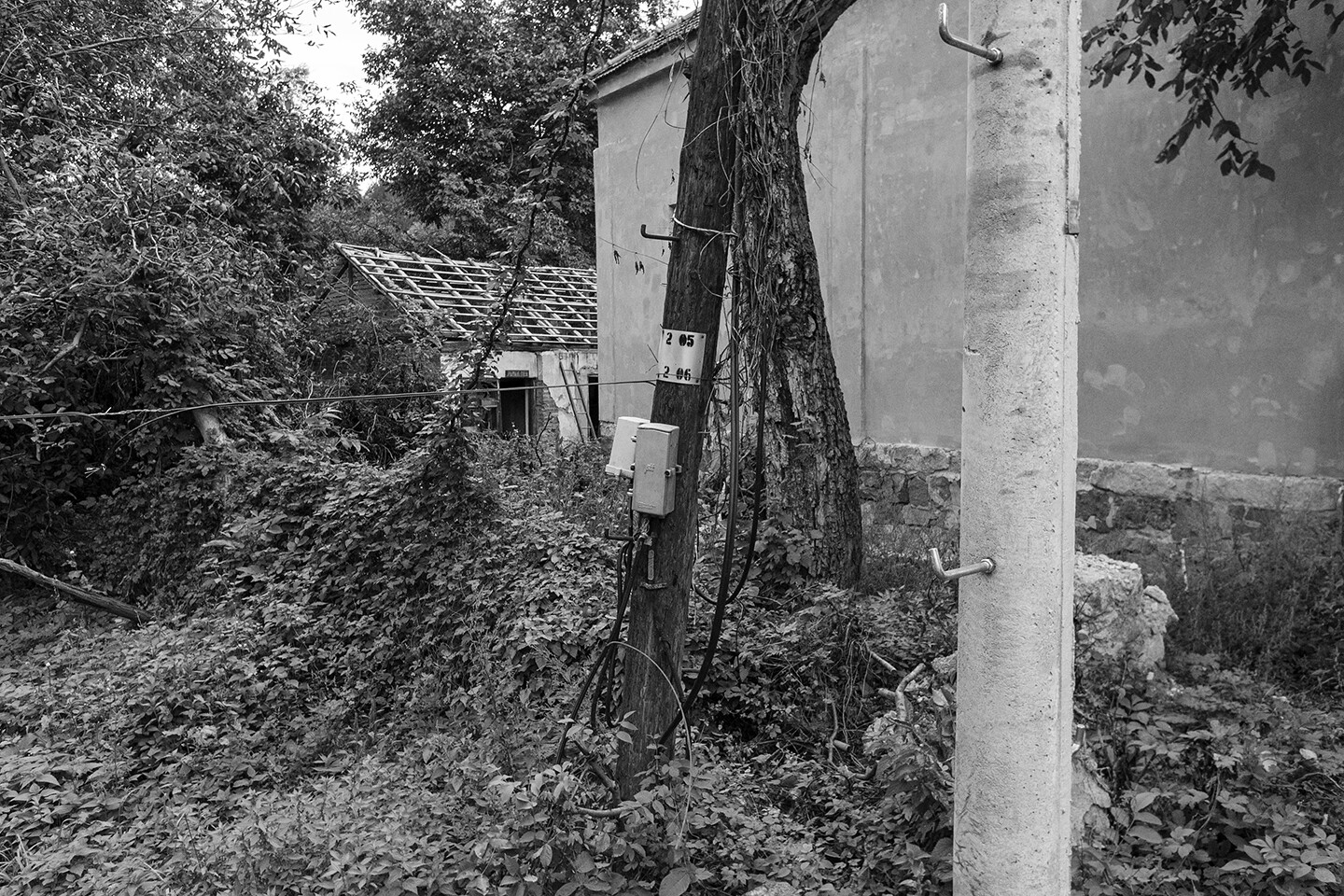

The edges of the Krivelj village during the walk by Jelica Jovanović and Miloš Božić. Photo: Vladimir Radivojevic. Commission by What Could/Should Curating Do? (WCSCD).

The inquiry’s moments of adjacency, in which embodied practices became physically proximate, encouraged participants to consider non-colonial futures. 2 Embracing bodily perspectives, “As you go…” drew part of its guiding methodology from philosopher Mary Graham’s thinking about the Indigenous sense of “walking with” and the kind of relations it allows. 3 For Ćirić, the bodily knowledges acquired through walking, listening, and learning from others enables us to think critically about the limits of our own perception. Further, as a wholly quotidian action and a method, walking with others sidesteps the power imbalances that attend curatorial work—for instance, the institutional hierarchies and hegemonic tastes that dictate what counts as cultural expression. In the logic of the inquiry, walking together created a space for the equitable exchange of social and cultural knowledges based upon being with another and moving at the same pace, rather than a predetermined leader imposing a set rhythm upon artists and audiences.

Walking alongside Ćirić in “As you go…” were other research partners—or “cells,” in the inquiry’s lexicon—from sites transformed by the industrial development associated with the Belt and Road Initiative. These included artists, curators, and organizations such as Robel Temesgen and Sinkneh Eshetu (Addis Ababa), ArtCom (Astana), Bor Public Library (Bor), What Could/Should Curating Do? (Belgrade), Guangdong Times Museum (Guangzhou), Zdenka Badovinac (Ljubljana), and the Rockbund Art Museum (Shanghai). As well as coming from “extractive zones,” to use Macarena Gómez-Barris terminology, the “As you go…” cells all emerged in places that share similar social, political, and cultural legacies, specifically those of socialism, self-determination, and nonalignment. 4 Today these places contend with similar geopolitical forces and continue to parse the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Digging where they stood, to paraphrase Ćirić, each of the partner cells examined these points of connection in their own contexts with an interdisciplinary team of researchers. 5 These teams in turn uncovered a range of urgent issues exacerbated by the conditions of extractive capitalism, such as the effect of mining on local water resources (Bor and Lake Balkhash) and of industrial development on social and spiritual practices among cultural minority groups (Addis Ababa and Bor). 6 Following a process-oriented approach, partners introduced these local issues into the inquiry to shape its development. In this way, the inquiry progressed within and from each locale’s sociocultural geography, that is, within and from a “submerged perspective,” which Gómez-Barris suggests can resist the divisive logic of colonial capitalism that “dramatically divides nature and culture through new forms of … exclusion” for the purposes of streamlined extraction. 7 Researchers also presented place-based case studies, for example, when the writer Sinkneh Eshetu (pen name O’Tam Pulto) shared his research into the spiritual aspects of landscape architecture to convey the link between the effects of industrial development in Ethiopia, where privatized construction projects are eradicating local customs, and those in Bor, where capitalist extraction is also dispossessing citizens of their communal history. Over the course of the inquiry, “As you go…” held these immersed perspectives of Bor and the other the sites alongside one another, to connect disparate socio-geographies through their commonalities and thereby curate a space for new transnational solidarities. 8

Visit to Bor Zijin headquarters, September 16, 2022. Courtesy What Could/Should Curating Do? (WCSCD).

As a curatorial project, “As you go…” laid the ground upon which we participants—local citizens, inquiry partners and researchers, and guest art workers such as myself—walked together in Bor. The inquiry’s artistic program consisted of a daily public walks, presentations, performances, and communal dinners, each of which brought participants into contact with urgencies relevant to Bor, such as the effect of direct foreign investment on the city’s local social and ecological landscapes. 9 The curatorial approach of “As you go…” expanded the idea of what constitutes an artistic gesture. Acts of communal reading, walking, eating, and mourning gave the inquiry a haptic quality, something Tina M. Campt describes as more than just a sense of touch but “the link between touching and feeling, as well as the multiple mediations we construct to allow or prevent access to these affective relations.” 10 As I walked the streets of Bor with the other participants, I felt these relations form among our group.

Most of the urgent issues in Bor taken up in “As you go…” emerged from the city’s historic copper mine, an omnipresent entity that I first experienced on the drive into the city as a monumental dune of gray-blue debris scarred with acrid ochre veins. Before 1992 and the breakup of Yugoslavia, the mine flourished, providing an international symbol for the potential of Yugoslavian socialism. Now the mine and its heap of “living mud” tell a contemporary story of privatization and neocolonial reindustrialization, the effects of which have left physical and intangible scars on the city, which have only deepened with the Belt and Road Initiative’s recent impact on Bor. In 2019, the Serbian government sold the majority share in the city’s mine and smelting plant to Zijin, a multinational mining group headquartered in Longyan, China. As Zijin moved into Bor, the pace of neoliberal privatization and industrial deregulation quickened. Forced relocations severed local citizens from the land they have occupied for centuries and from the social practices that have upheld Bor’s communal spirit. Zijin has since become a dominant influence in the city and has attracted a new workforce of Chinese citizens. Rather than mixing, the Serbian and Chinese communities in Bor exist in parallel worlds, each with its own areas within the city, its own restaurants, its own places of leisure, and indeed its own reasons for working in the mine. The majority of the Chinese community has moved to Bor short-term to reap the economic rewards of working for Zijin. To gain the most from their time in Serbia, these miners are nearly continuously on the clock. Ceaseless labor conflicts with Bor’s post-socialist spirit, which holds work and leisure in equal esteem. Among the city’s Serbian population, this clash of mentalities has revived deep-seated cultural stereotypes and sparked suspicions about how and why these foreign workers came to the city. 11 These perceived sociocultural differences illustrate the divisive logic at the heart of extractive capitalism and the very neocolonial conditions that “As you go…” sought to address in its inquiry. 12

Walk by Jelica Jovanović and Miloš Božić. Photo: Vladimir Radivojevic. Commission by What Could/Should Curating Do? (WCSCD). Photo: Toby Üpson.

Daily walking tours through Bor conveyed how the city was smothered by the thick soot emanating from the mine, literally and metaphorically. Organized by the architect Jelica Jovanović and led by a different local guide each day, these tours made apparent both the perspectives and needs of Bor’s citizens and the harms inflicted on the city by extractive capitalism. In the first of these tours, Miloš Božić, an engineer, took participants from an anemic mound at the mine, once the heart of Božić’s village of Krivelj, to a nearby valley of abundant green smallholdings, where the village was relocated after the mine was expanded through foreign investment. As we walked, we not only witnessed how the mining process has defaced the land. We also heard Božić recount the social history of Krivelj. Božić also laid bare how reindustrialization, catalyzed under the Belt and Road Initiative, has devastated the local community, for example by leaving the citizens’ council of the village without a building in which to meet and discuss local issues. In the publication As you go…, Jovanović provides further evidence of the way reindustrialization has injury local social life: When the mine was organized along socialist lines, it reinvested profits in the city and its infrastructure, providing Bor’s citizens with some of the highest living standards in Serbia. 13 Today, all profits are syphoned into Zijin’s corporate pockets, leaving the city with dilapidated roads, derelict buildings, and the remains of a once-functional transport system.

The second tour organized by Jovanović took us to Bor’s greenmarket. Here, Katica Radojković, a sought-after cheesemonger, discussed how the globalized food industry was straight-jacketing local citizens into shopping at large, multinational superstores—in part due to the fear of eating local food poisoned by waste from the mine—while at the same time sparking anxieties around food scarcity. As I learned earlier that day from the staff in my hotel, across Serbia there are rumors of an impending dairy shortage, but Bor’s market was full of locally produced food, including Radojković’s soft cheese, which was zingy and fresh. In our third tour, Nemanja Stefanović, a student, guided our group through Bor’s three streets. As we walked with him, he spoke about growing up in the city and how options for his future were limited in Bor, leaving him unable to pursue his acting and filmmaking ambitions locally and prompting his relocation to Belgrade to study political science. Listening to Stefanović speak outside of Bor’s defunct railway station, it became apparent to me how the biopolitics of extractive capitalism have closed the city to the outside world, which is counter to Bor’s social and cultural history. When the mine was a socialist enterprise, the well-maintained railway station provided direct access to Belgrade, the wider Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and beyond, allowing Bor’s citizens to travel and experience life beyond the city’s three streets. Now, rail travel out of Bor is primarily for the raw copper extracted from the mine.

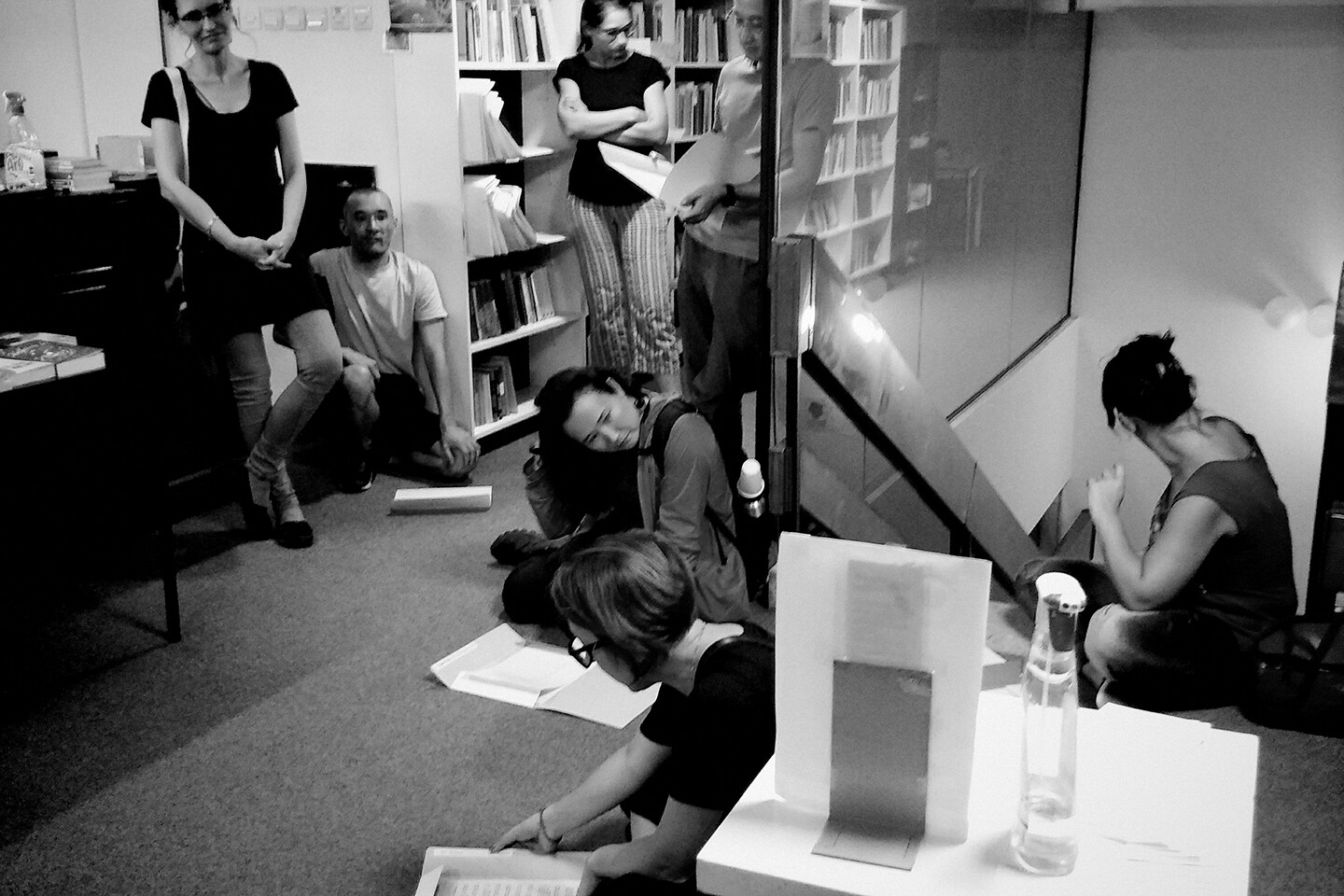

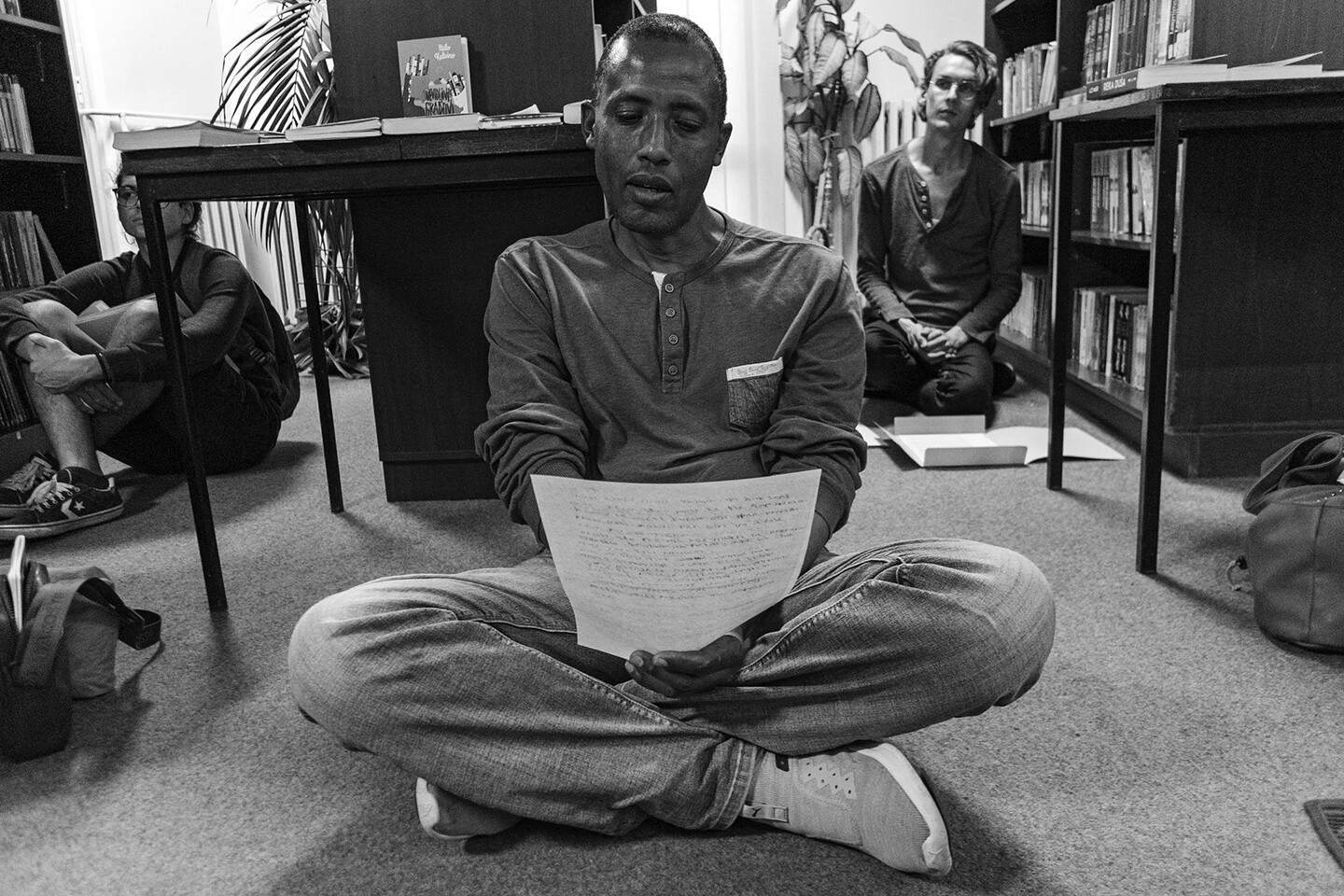

Jasphy Zheng, Stories from the Room, 2020–ongoing. Text and collective reading, Bor Public Library. Sinkneh Eshetu reading a contribution in Amharic. Photo: Vladimir Radivojevic. Courtesy What Could/Should Curating Do? (WCSCD).

Foregoing a focus on artistic engagements that only privilege looking and listening, these slow, hyperlocal tours provided participants with an embodied sense of the issues troubling Bor and the multiple, distant localities engaged in the inquiry. Alongside these embodied modes of cultural exchange, other artistic gestures curated as part of the inquiry’s public program also embraced haptic knowledge to establish transcultural connections between and beyond the localities that formed “As you go….” One example was Jasphy Zheng’s ongoing project Stories from the Room. 14 Developed and nurtured over Covid-19 lockdowns, the premise of Zheng’s project is simple: participants from across the globe share their own writing about their experience of the “new normal” we find ourselves living in. Collected as a growing archive of texts in different languages and dialects, the project has been exhibited in key cultural centers across the localities involved in “As you go…” and elsewhere, including CCA Kitakyushu (Kitakyushu, Japan); Rockbund Art Museum (Shanghai, China); and Burtukan’s Coffee, Alem Buna, Lime Tree, Entewawek Coffee, Qawa Coffee, and Tomoca Coffee (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia). Each manifestation of the project involves the display of the existing archive, often on simple shelving, along with new contributions. The Bor Public Library has acquired over two thousand texts created for Stories from the Room. Catalogued by librarian Violeta Stojmenović, the texts were displayed for “As you go…,” flowing in and out of the library’s collection of social, cultural, and personal history books. Following Zheng’s prerecorded presentation about the project, Ćirić prompted participants to pull a folder of texts from the library’s stacks and join a collective reading of its contents. As each of us read aloud, we created a polyphonic assembly of voices as Serbian flowed into French, into Mandarin, into Japanese, into Italian, into English, into Amharic. Against the silence of the library—and indeed of the spaces most of us were confined to during lockdowns—this “sculptural monument,” as Zheng refers to it, transformed the quiet moments of personal reflection collected in Zheng’s project into something haptic. 15 That is, through our collective reading, empathy and relationality converged in an affective atmosphere, connecting us all on a embodied level with the voices of the other participants in the room and those of the contributors to Zheng’s project. Sitting with the sensorial residue of this reading, I was reminded that moments of silence are not necessarily absences of sound but rather can be occasions for convivial quiet. By tuning into the barely audible frequencies that surround us in the flows of our day-to-day lives—an auditory counterpart of looking from a submerged perspective—we might find common connections across social and geographic difference.

Robel Temesgen’s Mourning Performance provided another poignant example of how an expanded definition of artistic gesture can establish affective connections between disparate places and peoples. Drawing on both traditional Ethiopian mourning rituals and the different cultural practices of lamentation discussed in the book Despite Dispossession: An Activity Book, the premise of Temesgen’s collective workshop and participatory performance was to collectively mourn the sites around Bor that have been lost to or harmed by extractive capitalism. 16 After a brief introduction by Temesgen, our group devised a minimal choreography of mourning—a quiet walk with heads bowed and hands clasped—and selected a site where we would perform this ritual: the derelict railway station that Stefanović guided us to on his city tour. Our walk to the railway station was slow, timorous. One foot in front of the other, we moved in elegiac procession. Upon arriving at the station, a group of older women led us inside. Once a grand, modern structure and a monument to Bor’s prominence, the station’s interior is now a harrowed carcass covered in broken glass, weeds, and graffiti. Rubble clogs the building’s once healthy pedestrian arteries. Our procession paused on the pedestrian bridge that crosses over the tracks to perform our mourning. Straight ahead of us was the mine’s monumental slag heap in the fading evening light. Ten minutes passed, which could have been hours, and an older woman spoke in Serbian of how the railway station once allowed the citizens of Bor to venture beyond the city, to commune and converse with people and places elsewhere. Now the station haunts Bor as a ghost, ruined in the drive for profit, which is privileged over the needs of the people who call the city home.

Hu Yun, The smoke from Bor, 2022. Commission by What Could/Should Curating Do? (WCSCD). Photo: Vladimir Radivojevic.

Each day of Bor Encounters ended in a similar manner, with a walk beyond the city’s three roads to a pristine restaurant where the beautifully simple gesture of dining together dissolved sociocultural divisions. With an interior of shining white walls and tidy shelves decorated with precisely arranged bonsai trees, this establishment’s aesthetic was very different from the other venues I had encountered in the city, with their rustic, mismatched decor. One of the first Chinese restaurants in Bor, the establishment’s brilliant interior was striking, as was the fact that for most of the inquiry’s Serbian participants this was their first encounter with Chinese cuisine. Though it may seem quite rudimentary, this venture into Chinese culture had a powerful sociocultural impact, breaking down some of the ideological divisions ingrained in the social landscape of Bor since Zijin took control of the city’s mine. The dinner was organized by the artist Hu Yun in collaboration with the restaurant’s chef, Qiu, who came to Bor from southern China. While saving to renovate his restaurant, Qiu has been working in Zijin’s canteens, preparing food for the mine’s Chinese workforce. Together Yun and Qiu devised a large family-style menu of southern Chinese dishes modeled on the offerings in Zijin’s canteen. But unlike the at the mine, where one’s position within Zijin governs what food one can consume, in our communal dinners this socioeconomic hierarchy was suspended, with each of us serving ourselves from the same large platters. This act of culinary equality not only established an honest feeling of community but resisted neocolonial logics that divide people according to ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Further, with such a simple premise—sharing a meal with one’s neighbors—the encounter created by Yun afforded the opportunity for two very different cultures to connect in a corporeal way. Rather than taking an epistemic approach, in which ideas of difference are discussed and analyzed, Yun and Qiu’s dinners haptically transformed our sense of being together, upending the divisive stereotypes and rumors that have proliferated amid Bor’s hasty entry into neocolonial globalization. Seated at a communal table and sharing lovingly prepared platters of delicious food, we felt in our bodies this exchange of knowledges across cultures and geographies.

Unlike curatorial projects that fly in and out of a place to perform some critical cultural work or to impart some epistemic gift, “As you go…” proceeded with neither a predetermined outcome nor a presumed destination. By working from the submerged perspectives of specific localities and connecting them with others, the inquiry’s process-oriented approach not only expanded its horizons but shifted and multiplied its points of view. Through a broad range of embodied aesthetic expressions, “As you go…” established an important premise for curatorial practices looking to resist a logic of coloniality and to uncover “the worlds within the world we think we know,” to quote Gómez-Barris. 17 Walking with those engaged in the Bor Encounters, I was able to bear witness to and join in this thinking, as it was made as tangible as the roads under our feet.

The Belt and Road Initiative is loosely based on the historic Silk Road. See Andrew Chatzky and James McBride, “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative” Council on Foreign Relations, January 28, 2020 →.

My use of the term “adjacency” here comes from the sense of the word developed by Tina M. Campt in A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021), 171–72. For a more detailed use of the term in a curatorial context see, Toby Üpson, “Adjacency in the Collection,” in Women, Collecting and the Cultures Beyond Europe, ed. Arlene Leis (New York: Routledge, 2023), 229–33.

See Mary Graham, “Aboriginal Notions of Relationality and Positionalism: A Reply to Weber,” Global Discourse 4, no. 1 (May 2014): 17–22 →.

See Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham, N.C.: Duke University, 2017), xix.

Biljana Ćirić, As you go… roads under your feet, towards the new future (Milan: Mousse Publishing, 2022), 109.

For a full list of projects associated with “As you go…,” see →.

Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone, xvii.

More examples are gathered in the inquiry’s publication. See Ćirić, As you go….

Alongside the public elements of Bor Encounters, there were daily “invisible encounters” between the “As you go…” partner cells. Rather than focusing on research topics and findings, these convenings provided an opportunity for partner cells to discuss the trajectory of the project and share their thoughts about the inquiry’s future.

Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2017), 99–100.

A rumor circulated around Bor that the Chinese workers were political exiles or prisoners put to work in the mine to maximize Zijin’s profits.

See Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone, xvii–xx.

Jelica Jovanović, “Ecology within the High Tide of Direct Foreign Investments: Navigating Deindustrialization and Decommunalization in the Serbian Mining City of Bor,” in Ćirić, As you go…, 110–34.

Further information about the project and its iterations can be found on Jasphy Zheng’s website →.

See →.

Despite Dispossession: An Activity Book, ed. Anette Baldauf, Janine Jembere, and Naomi Rincón Gallardo (Berlin: K. Verlag, 2021).

Macarena Gómez-Barris, Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents in the Americas (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018), 113.