Since its March 2022 launch, LA ESCUELA___, a project initiated by artist, architect, and educator Miguel Braceli with the nonprofit Siemens Stiftung International, has progressively developed its educational programming, producing editorials, live conversations, artistic projects, and public events, both online and in person. The digital platform has come to life, not as a repository but as an active space for dialogue and encounter.

Elaborating on the pedagogical framework of this platform-in-progress, Braceli speaks here with curator, educator, and researcher Sofía Olascoaga. The conversation unfolds some of LA ESCUELA___’s structural elements, the Latin American context it seeks to recognize, the inherent dilemmas of the art–education relationship, and the socialization of the project’s activating experimental practices. Braceli and Olascoaga also discuss ways of broadening access to art education and complexifying the history of learning resources within art practices that intersect with education and participation.

Sofía Olascoaga: Before this conversation, I’ve been observing LA ESCUELA____’s social media and virtual platform, where your essay “The Naked School” positions amazement and disappointment as opposite ends of a range in which the possibilities of experimentation may fall. The essay articulates and proposes an educational space that is able to support in a lively, non-homogenizing way a “proposal of a building without walls which aims to bring artistic production closer to the social and political contexts that surround them.”

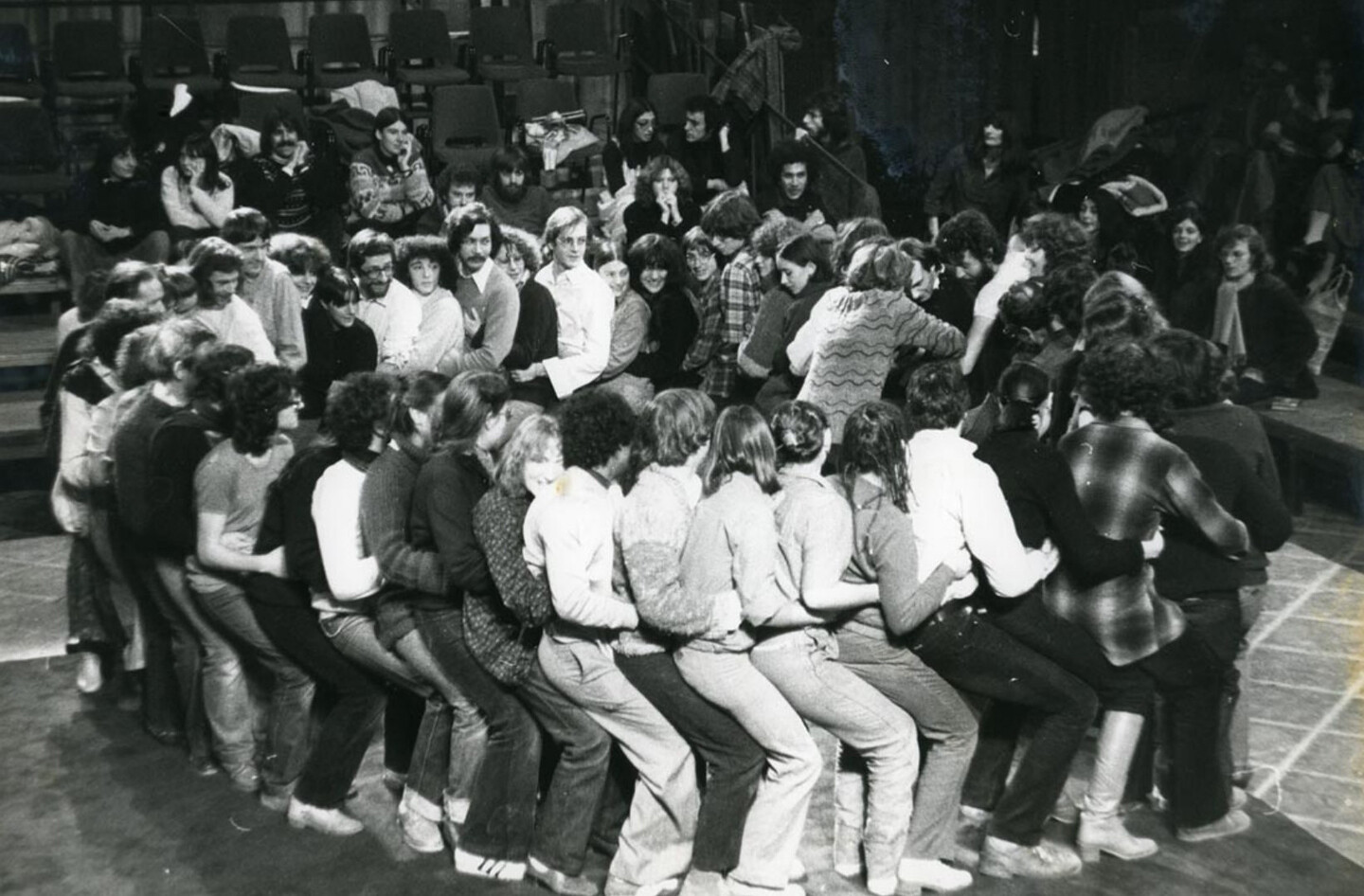

Miguel Braceli: This idea is at the core of LA ESCUELA___: to bring education closer to the social and political realities of specific contexts and to learn from and act on them. “The Naked School” emerged as a critique of my experience as an MFA student in the United States and questions a model that is focused on white-cube galleries and replicating the institutional market-driven dynamics of the art world. The Naked School, the school without walls, derives from the legacy of art and education practices in Latin America. It could be a building in Ciudad Abierta (Open City) 1; a performance at the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella (Torcuato Di Tella Institute) 2; a party at the Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage (Parque Lage School of Visual Arts) 3; a school founded by Francisco Toledo; a class taught by Lygia Clark; or any number of artist projects that have sought new experimental spaces and places for education.

LA ESCUELA___ was intended as an artist-run platform that seeks to make learning a collective practice in public space. It is not a traditional school offering instructional classes but rather a space for radical experimentation where creators, universities, students, institutions, and communities assemble around the possibilities of art as education. This occurs through the development of collaborative “formative projects”—performances and interventions, among other manifestations—that create learning spaces in public as art practice. These pedagogical approaches are also addressed through researched editorials and online and on-site public programs. The platform is now realized as an open space where all programs are free in order to engage different publics and defend free access to education.

SO: So, we could think of the digital platform as a building in which voices, references, examples, proposals, and practices come together into what I imagine is a polyvocal and ongoing conversation.

How do the diverse, transgenerational, and translocal voices in this ensemble communicate with each other? More than a compendium or a delimited set of references, I am thinking of each dialogue as a collection of progressive, resonant, interwoven, and also (perhaps, hopefully) discordant perspectives. Conversation might originate in not one but several dissimilar, diverse, particular, situated, contradictory, and above all, lively contexts from which each conversationalist speaks.

MB: Conversation is the basis of LA ESCUELA___’s different spaces and programs because communication is inherent to education and the platform is a collaborative project to think about and activate experimental schools. The platform’s architecture appropriates the organizational structure of a traditional school but expands its limits and subverts its logics and dynamics. For example, “Campus” is a digital and physical space, a hybrid system of online laboratories and classrooms that also take place in public space as collective works where the medium is education. “Emeritus” assembles key figures from the fields of art and education in Latin America—Gego, Francisco Toledo, Lea Lublin, Helio Eichbauer, Claudio Perna, Celeida Tostes, Frantz Fanon, Lina Bo Bardi, Rubens Gerchman, Roberto Valcárcel, among others—whose legacy we as a platform are researching to review, question, and dialogue with their methodologies. “Faculty” are the collaborators who contribute editorials, formative projects, and public programs. In this intergenerational exchange, historical research and contemporary creation come together, producing conversations and projects that respond to and grapple with the animating issues of art and education.

This work resonates, for example, with the impact of authors such as Paulo Freire, a pioneer of critical pedagogy; Gabriela Mistral, a poet and advocate for the political role of education; and Simón Rodríguez, who took the first steps toward building a Latin American identity in the early nineteenth century. Beyond their anti-colonialism, we understand these figures’ emancipatory politics from a pedagogical perspective, especially in their regard for free and radical education.

There is also tension in highlighting multiple voices and practices, as we see, for example, in the development of the formative projects in public space: the same idea of education as art in the “Laboratories” is not the same as in the work of Nicolás Paris or that of Patricia Domínguez, both Faculty members. Each project responds to different interests, localities, and contexts. Additionally, digital laboratories gather participants from across the region, which further enhances transgenerational and translocal exchange. Through this kind of participation in the educational programs and dialogues, the platform achieves its primary goal of creating a dynamic and complex community.

SO: Beyond LA ESCUELA____’s online platform, happenings “off-line,” free from internet-connected devices and social networks, produce a creative surplus that fuels curiosity. These happenings serve as reminders to exceed the building without walls, despite the complexity of the readings and presentations housed in this robust digital container.

LA ESCUELA___ has also published dialogues on the educational work of artists from Latin America from previous decades, outlining a transgenerational account of the effects of those practices, spaces, and propositions over time. The dialogues are not an end in themselves, and they touch on subjective and contextual transformations influenced by these educational practices. One can think of them as crops that have germinated and will bloom with time.

What are the implications of referring to a context as “Latin American”? Is it relevant to continue to think of it as an actual region? How and where is this definition useful? For whom and for what purpose?

MB: Latin America is a culturally diverse, institutionally unstable, and politically convulsive region that has always sought to look inward to find an identity of its own and resist processes of colonization. “Latin America” is a construct or a place to be constructed, a territory historically marked by precariousness as an originating condition. Returning to the multiple voices that make LA ESCUELA___, in a conversation with Cecilia Vicuña we discussed “the precarious as a creative space” in the face of real Latin American contexts. This is something that can also be read in the Hélio Oiticica quote “From adversity we live.”4 This is not an apology for poverty or crisis but a demonstration of the will to create truly communitarian, alternative, and independent spaces based on care and solidarity.

Many of these approaches concerning alternative models based on community have recently developed from the fields of art and theory in other latitudes, but we, in the South, have come to them empirically, out of need. These approaches are also rooted in Indigenous practices and pre-Columbian cultures. Hence the richness of Latin American independent spaces, artist-run schools, and other forms of activism and participation. These models combine their self-administrative and educational aspects, and the value of their practices increases when they are conceived from and for education.

SO: LA ESCUELA___ responds explicitly and implicitly to the need to connect experiences within and beyond the centers of cultural and discursive production—particularly those in Europe and North America (or more specifically, the United States)—with those conceived under different circumstances in the countries that make up the so-called “Latin American” region.

However, in the context of colonization histories and their operability in contemporary culture, it seems relevant to recall the role played by canonical discourses in the formation of “legitimate” artistic practices, i.e., those recognized by the art market and institutions. In other words, art education and art history often reproduce centralized and hegemonic thinking even in artists educated “on the periphery.”

Those of us trained as cultural agents in South America, Central America, and the Caribbean (regional designations that are necessarily questionable) likely studied in capital cities or urban contexts. There, the frames of reference, discourses, authors, and readings from which we learned were configured in such a way that we encountered the art historical narratives and iconic figures of Western Europe and the United States before those of our own countries. In addition, our education was marked by a profound ignorance and erosion of diverse local cultural histories and the particular differences of neighboring countries with which we share much closer affinities and the consequences of institutional and structural crises.

How might LA ESCUELA____ promote deep engagement with these specific regional contexts and recognize their power and complexity so as to address our ignorance of them at local, intercultural, and transnational levels?

MB: That is precisely one of the premises of the project, to learn from and with each other and to compose a network of proposals that resonate with one another. Research, educational practices, and art projects can articulate themselves and nurture future work. Hence the decision to use a name in Spanish, without translation, which is not free from colonial associations but is capable of consolidating a shared territory. Latin America is a collective identity construct that encompasses a wide geographical, historical, linguistic, and cultural diversity. One of the keys to approaching this shared territory is through history and learning spaces, and this is where we create dialogue between creative agents who might not have exchanged ideas themselves, for example, Lygia Pape with Diego Barboza, Lygia Clark with Manuel Casanueva, Antonio Caro with Felipe Ehrenberg, Antonieta Sosa with Margarita Paksa, and so on. Many of these artists have produced globally recognized art historical work—largely a result of the legitimizing processes of museum institutions—whereas we still have much to learn about others. With LA ESCUELA___, we also want to provide a platform on an international scale to very important figures such as Roberto Valcárcel and Mirtha Dermisache, who are still only known locally. We believe that sharing research can generate regional connections between neighbors and be of interest to a global, international audience. LA ESCUELA___ aspires to be a platform for and about schools and a collaborative project that creates schools. The aim is not only to set our eyes on Latin America—as is often the case in foreign Latin American studies programs—but also to place our feet on its ground, to situate ourselves in order to invest in our actions and efforts in the region.

SO: Undoubtedly, common ground is necessary to explore possible deep resonances among diverse practitioners. It also allows cultural agents to recognize the consequences of colonization and current colonialities and their permutations in each specific context, generating in turn certain agencies, practices, and dialogues against official narratives. These counternarratives can be communicated through critical, propositional languages, means, and processes, not only in each context but from each artistic proposal.

How does LA ESCUELA___ intend to provide a site where diverse regional conversations come together with artistic dialogues and specific interlocutions?

MB: Beyond the diversity of a collective archive generated through research and editorial content, the formative projects are an appropriate place for regional exchange. In “Classrooms,” guest artists develop on-site projects in collaboration with students, teachers, and local communities. To complement these, “Laboratories” are online spaces where people from different regions of Latin America participate in a kind of ongoing, free-form seminar. We understand these programs as collaborative projects where contexts, roles, and forms of creative production can be dislocated. In both cases, some displacements produce dialogue and are addressed to the public realm, either from digital “Laboratories” or from the specificity of the on-site “Classroom” locations.

SO: I’m thinking about the inherent limitations in documenting, editing, and curating. These processes always produce, to greater and lesser degrees, an “off-line” or an “off-camera” portion, and we must remember to keep in mind the experiences that fall outside a certain proposed framework. What we do not see, or what is not recorded, are often the subjective, dissimilar, and even discordant experiences of the participants in a collective encounter.

Considering artistic and educational practices and the codes and media through which we document, articulate, and socialize them, how can we communicate, share, or make public our practices, their power, their validity, and the needs and drives they entail?

MB: Documentation is one of the biggest challenges for educational practices. The most important thing is to make peace with the idea that, in formative projects, for instance, the primary audience is the students, participants, and community, and so their dynamics generate a nontransferable experience, and therein lies the true value of the work. However, acknowledging these practices as art also implies communication with an external, secondary audience. For that, one way is to bet on sensibility, to turn documentation into a trigger for imagination. As with any work of art, it is not a documentary record but a sensitive construction to create possible situations, situations that only occur in the dialogue between the work—as documentation—and a new spectator.

It is important to understand that documentation is not a form of validation but an evocative space for expressing the multiple possibilities of the original work. Another way is to record a project’s pedagogical codes so that it can be communicated through its methodologies. That is to say, to interpret the original work through processes, as alterable or questionable strategies capable of becoming an object of study. A good example of this is Augusto Boal’s workshops for the Theater of the Oppressed, a space where performing arts and social practices come together through education, and it is thanks to his methodologies that these workshops continue to be useful today.

SO: One of the frequent tensions in the intersections of art and education lies in the exchange between the legitimizing systems of the art world—how objectual or curricular works’ presentation, exhibition, and reproduction requirements are codified—and the openness and uncertainty of destabilized learning processes that must take exploration as a precondition and dispense with objectifiable results.

MB: Yes, and this is where art education should not adapt itself to the protocols of the art world but rather learn from radical education. At LA ESCUELA___ we seek to approach formal spaces of both education and exhibition in order to transform their dynamics and open other spaces of creation where the artistic project becomes a formative project. In Mexico, for example, we are working with the Museo Experimental el Eco, the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo of the Autonomous National University of Mexico (MUAC-UNAM), and the UNAM Faculty of Arts to develop a formative project with artist Adrián Balseca that explores issues of sustainability and mobility in Mexico City. The project involves designing pieces that integrate local knowledge from car repair shops with students’ research to produce objects that can be activated in public spaces but, above all, function as a collective creation process. Emphasizing the methodology, turning the audience into a community, operating in public spaces, and creating space for collective learning can destabilize artists and institutions as well as the dynamics of public space. This field of friction is a fertile territory where potentialities are as endless as the results are uncertain.

These practices are not new, but their complexity and dynamics outside the art system have made them difficult to consolidate, perhaps because of their non-objectifiable nature or their total lack of objecthood. On the other hand, they have not disappeared either and continue to renew themselves; hence the interest in consolidating a platform: a common space.

SO: This kind of work is a personal and communal reminder that we are dealing with living practices, the unrecorded aspects of which fortunately persist among the participants. Conventional means of documentation do not usually reflect the experiences of participants or common occurrences like polyvocality, disagreements, contradictions, and trivialities.

On the one hand, learning requires or demands a temporality that exceeds that of the event, which invites us to reflect on the experiential dimension of learning. It is possible to sustain meaning without objectifying, commodifying, flattening, sanitizing, or reducing the experience, or rather, by honoring the complexity of each situation, participant, and context. But what happens to those subjective experiences that cannot be documented and their possible meanings over time?

On the other hand, beyond the discussion of documentation and socialization strategies, I think it is important to reflect on the ways in which contemporary art discourse also “commodifies” or commercializes educational and participatory practices. In recent decades, “social practice,” “community practice,” and “socially engaged art” have entered the critical context and the discursive field, determining particular sites where critical production is generated.

MB: This commodification through language tries to assign fixed meanings to practices that are by nature indeterminate. In this case, learning practices seek to respond to certain categories instead of finding their own dynamics, even when their place is at the liminal spaces between art and education. It is there also that language becomes exclusionary, and English, as the supposed global language of art, leaves out practices that come from other cultures and that do not fit in the discursive standardization of a single language. For example, in what category do we insert or in what way could we refer to the Oiticica’s Parangolés? Sculpture? Performance? Social practice? This is not only a conflict between cultures and languages, but also evidence of the tendency to make art an increasingly hermetic, encrypted, and inaccessible space. This commodification in art language is a market and marketing issue, which is completely opposed to the public vocation of education.

SO: I agree, but it also refers to codes of presentation and the reproduction of what certain logics of productivity and professionalization demand and uphold as contemporary art within an efficient production model. In view of this, I think it is necessary to remember the difference between the logics of event versus process and how collectivization challenges conventions like authorship in the educational or experimental art-learning field.

MB: Absolutely. Authorship in the educational field will always be a shared space, and that is why it is so difficult for the art world to acknowledge these creative processes as artistic products. The same tension exists between teaching art as a professional career and learning as an artistic process. Regarding the former, in art schools students are trained to enter an art system that we know does not work, instead of opening up spaces to transform it. At LA ESCUELA___, we do not intend to solve this problem because we do not educate artists as professional training, but we do work in alliance with universities that do. In a way, this platform is a space that exists on the margins of that reality, emerging as a reactionary response to the system in order to speculate together on how to build new ways of learning and creating within shared spaces. Regarding the latter, approaching artistic practice as a formative project is the main interest of LA ESCUELA___. Working from and around public spaces, we are attempting to locate a place in the relationship between art and education to inhabit the social and political challenges of the present. On the one hand, art offers the freedom of creating; on the other, education is the realm where transformations can happen. To turn education into an artistic medium is to open up an endless field of possibilities, shifting the interest toward processes and displacing singular objects in favor of collective learning. Thus, art becomes a form of knowledge production that manifests learning as an emancipatory act.

Translated from Spanish by Marianela Díaz Cardozo.

Ciudad Abierta was an integral experience of architecture, life, work, and study founded in 1970 on the dunes of Ritoque, Chile by poets, architects, designers, sculptors, philosophers, and artists, mostly from the School of Architecture of the Catholic University of Valparaíso. Among them were Godofredo Iommi, Alberto Cruz, Claudio Girola, and Manuel Casanueva, who were dedicated to experimenting with students and residents of Ritoque on a public pedagogy designed around writing poetry and making crafts. See →.

The Instituto Torcuato Di Tella was an artistic avant-garde educational institution located in Buenos Aires, Argentina, well-known for its unconventional and provocative programming. The “experiences” carried out at Di Tella in the late 1960s brought together young artists who sought to overcome the objectual notion of the artwork by creating situations that involved the body, space, and time in installations, performances, and happenings. Among the teachers and students of the institute were Julio Le Parc, Lea Lublin, Marta Minujín, León Ferrari, Margarita Paksa, and Roberto Jacoby, among others. See →.

The Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage (EAV) is a school for artists, curators, and researchers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, created by Rubens Gerchman in 1975. At its founding, it was considered a center of resistance to the Brazilian military dictatorship due to its democratic, festive, and openly political collective practices. In 1984, EAV hosted the Como vai você, Geração 80? (How are you, Generation 80?), a comprehensive artistic experience that was fundamental to the development of participatory art in Brazil in the 1980s. See →.

Miguel Braceli and Cecilia Vicuña, “A Precarious Education in the Creative Sense,” LA ESCUELA____. See →.