1. Why did you decide to go into teaching?

One of my important mentors when I was an undergraduate at UC Berkeley was Jerome Karabel, a sociologist of education. I was his research assistant on a project about the politics of the intelligentsia that considered, in a neo-Gramscian and neo-Bourdieu-ian way, how class and power play into intellectuals’ political affiliations.

As a high school student my first loves in visual art were Dada and surrealism, and I was galvanized by the surrealist proposition that unleashing the unconscious from bourgeois norms would foster collective creativity. Then everyone would become an artist! But of course, the issue of who speaks for whom and whose (un)conscious is liberated in a revolution, surrealist or otherwise, is historically a deeply problematic one. Karabel’s research was formative, addressing how the polemics and pedagogies of the cultural elite can and can’t promote oppositional or revolutionary values.

Then suddenly, in 1995, the University of California Board of Regents overturned the system-wide affirmative action policy Karabel had drafted, and the number of Black, Latino/a, and South Asian students admitted to Berkeley plummeted. His work, and by extension mine, pivoted to mobilizing state and national communities to reinstate some notion of equal outcomes and cultural fairness in higher education.

A high-quality liberal arts education should remain universally accessible and not only to those families who already appreciate education. When I was a high school student in San Bernardino, California, I remember going into classmates’ homes where the only printed volume was the telephone book. That kind of uneven distribution of knowledge resources is something broad access to excellent higher education can counter. Education’s capacity to cultivate social change, as a means of expanding individual consciousness or facilitating social transformation through collective intellectual growth, is something that I value immensely.

2. What drew you to your school and what is your teaching philosophy?

In 2008, the year before I defended my PhD at Princeton, I was working full-time as a curator at Art in General, a now-shuttered space that was part of a wave of artist-run organizations founded in New York from the late 1960s to the 1980s. Even then I was also teaching contemporary art at Parsons and Sarah Lawrence College and working as an art critic. As much as I enjoyed working directly with artists, I ran into some problems about what I could write at a place where curatorial endeavors were not considered a protected form of speech.

Academic freedom means publishing without fear of reprisal. In 2009 Pratt offered me the newly created position of historian of contemporary art, which bridged the work I was doing in mid-century modernism to the curation and art criticism I was invested in.

“What is my teaching philosophy?” is an enormous question, one I’ll likely be answering my whole life. I believe practices of teaching and learning are mutually informing and interdependent, and I strive to practice an educational egalitarianism that, as Josef Albers once wrote, will “break through the boundary between those teaching and those being taught, because then everybody will be teacher and student at the same time.” The goal is to shift, as Albers wrote, from “giving information to giving experience.” And I don’t mean, nor do I think he did, “giving experience” as imparting expertise but rather developing a framework in the classroom that can enrich students’ and teachers’ experiences of life, by attending to others’ arguments, and by becoming more embodied by understanding the relationship of knowledge to life outside the classroom.

I have Anne Wagner to thank for introducing me to contemporary art; her seminar at Berkeley on performance and video art was revelatory. Classes led by Wagner and T. J. Clark, another great mentor, proved most essential to my career, not so much in terms of their content, stimulating as that was to be sure, but their pedagogical procedure: the links each made to their own manner of learning, research, and writing. They taught their research, and I am thankful to have witnessed and experienced that generosity, rife with all sorts of imaginative directions investigated in the seminar room. And like them, Jerry Karabel, and Ron Clark at the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program, I too teach theories and histories that challenge the reproduction of inequality and class, racial, gender, ethnic, and other unearned privileges. In the field of art history, that challenge often involves exploring how all form has meaning and how the material constitution and appearance of art forms represent decisions that can expand and change perception.

3. What theory and art history do you consider most essential for your students? What artist or artwork do you refer to most often?

That’s like choosing among my children! My main references in cultural production are drawn from the nineteen-teens to the present, though at Berkeley I focused on late eighteenth- to late nineteenth-century French art, studying with T. J. Clark.

I’ve recently taught classes on post-humanism and the Anthropocene that came out of the research for my book After Spaceship Earth, on the fraught relationship between art, technocratic utopianism, and social justice.

4. How do you navigate generational or cultural differences between you and your students?

When I started teaching, I was younger than many of my students, and now that’s rarely the case. My undergrads are now closer in age to my kids than to me. I’m not sure Gen X thinks of itself as old (prime of life, yo!), especially since baby boomers continue to be, like, the president of the United States or whatnot. “Generation” is hard to define since some wunderkinds near my age have been in positions of great power for a dozen or more years, but others will no doubt hit their stride in the coming years. Age may not define a generation, but the clarity and stakes of one’s vision can certainly transcend traditional, ageist markers of cultural relevance. This is why David Harvey, in his mid-eighties, is crushing it with his oversubscribed talks on Marx’s Capital.

On the topic of cultural diversity: I’ve regularly taught around New York, so my students have always been extremely international. But to the point below (in question 5), access to education is very unequal in this country, so what appear to be cultural differences are often very similar circumstances between somewhat homogenous populations.

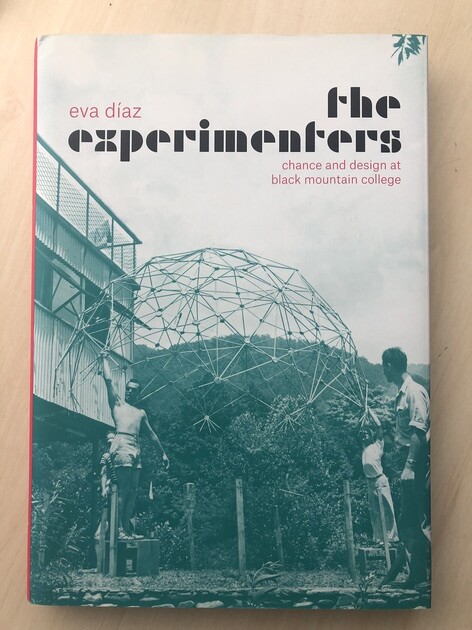

Eva Díaz, The Experimenters: Chance and Design at Black Mountain College, University of Chicago Press, 2015. Courtesy Eva Díaz.

5. What changes would you like to see in art education?

The expense of higher education (both public and private) is literally prohibitive to thought. Student debt depletes freedom, curiosity, and noninstrumental aspects of education. For some of my students, every moment in class is literally on the clock, costing them money. That pressurizes the experience of learning, as though instant rewards should come from their “investment.” This trivializes knowledge as merely something that can be deployed in a market.

Art is not a profession, really. There is no career demanding your art credentials, like in banking or law, only teaching jobs and semi-formal relationships with curators and gallerists who can display and possibly help sell your work. Art history is not exactly a profession either. In some ways it is the opposite: a form of creative production and research; an avocation orbiting a limited set of museum and educational institutions that can provide a salary to those awarded advanced degrees. In that sense, fine arts MFAs or humanities PhDs should be supported to the fullest extent possible by institutions of higher education, because there is so much risk in entering these fields and few paying jobs upon graduation. What mechanisms can be put into place to guarantee more equal educational outcomes, so that a livelihood in creative practice doesn’t necessarily have to be funded by private wealth?

Meritocracy is a fantasy, and the hustle to make ends meet leaches artistic freedom and research and creative time, turning labor into a distracting series of gigs. The problem of the expense of education is structural—part of a systemic creative disenfranchisement of those who do not spend every waking hour greedily seeking personal financial enrichment. Defending the value of education is a battleground; as a culture do we really believe money is the finest metric of success? It’s becoming almost impossible to educate one’s children without having first inherited or achieved great personal wealth, which essentially makes higher education the exclusive domain of the global ruling class and a tool of social stratification.

6. What is your educational background? Did you arrive at art from another field?

In the late 1990s I attended the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program, and Ron Clark, the steadfast leader of the ISP (for over 50 years!), hired me to teach in and later direct the curatorial program. For the next nine years I was able to reawaken to the amazing curriculum Clark created and experience the insanely talented and smart guest faculty Clark gathers to him and the remarkable alumni the ISP produces. One of the ISP’s long-term visiting faculty members is Hal Foster, and through his support I was able to attend Princeton and complete my PhD on a topic related to art and higher education, which later came out as the book The Experimenters: Chance and Design at Black Mountain College.

7. How have recent cultural movements and activism informed your curriculum?

Several years ago at Parsons and then at Pratt I taught a class called “Exhibiting Race” that focused on post-WWII exhibitions like the “Family of Man” and “‘Primitivism’ in the 20th Century” at the Museum of Modern Art and “Harlem on My Mind” at the Met, alongside late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century projects like “Mining the Museum” by Fred Wilson at Baltimore Contemporary, “The Short Century” by Okwui Enwezor at PS1, and “Only Skin Deep” by Coco Fusco at the International Center of Photography, among others. I’m taking that into the present to incorporate the important recent work decolonizing museums. The roots of protests against elitism and racism in art institutions runs deep, and the work Faith Ringgold, Lucy Lippard, and others in the Art Workers Coalition accomplished is connected to Decolonize This Place, Within Our Lifetime, Strike MoMA, and Comité Boricua’s recent struggles to make museums accessible and accountable to populations beyond the white and wealthy.

I’m also now working on a project that explores nonvisual experiences, such as olfaction, by examining the overvaluation of certain experiences in culture (vision and cognition, distance and analysis, for example) and the devaluation of others (smell and sensuality, proximity and the body). This is in some ways a late-Covid project about embodiment, and I’ve recently concluded a class on post-humanism and environment that takes up the trans-corporeal aspects of “lesser” senses like touch and smell (in a hierarchy crowned by sight) that were so stunted in our recent lockdown period.

8. How much structure or independence do students have in your courses?

My courses enroll undergrad and graduate students from all disciplines at Pratt: from animation, graphic, interior, fashion and industrial design, to painting and sculpture and art history, critical and visual studies, and performance studies, among others. I’ve been teaching for over twenty years, and I’ve become more mellow about student independence every year. After Covid’s major disruptions to students’ lives, my attitude is “If you’re into it, I’m into it,” meaning that students can work on just about anything they like as a final project as long as it takes written form and they’ve discussed it with me beforehand. I expect them to complete weekly assignments based on readings and their own research into contemporary art and to write short assignments based on prompts.

Art history MAs generally write research-based papers that might fold into thesis work, whereas another student might focus on a work of contemporary art their family ridiculed when they were a kid visiting a museum. I’m a research-based writer who cannot help but ground what I produce in my training in history and philosophy, but some written pieces benefit from greater speculation and less “scholarly” structure, and I offer that flexibility to my students.

9. How does the program connect students to the surrounding art scene? How do they learn outside the classroom?

#blessedtobeinnyc.

I’m kidding, but only about the metaphysics.

At Pratt we have almost limitless resources to experience art in New York City. Every semester I teach an art criticism class called “The Current Season,” a title I inherited that I initially thought retro and a bit weird but have since grown accustomed to and even a little fond of. In this class, I and the students create itineraries for seeing museum and commercial gallery shows during New York’s fall and spring art “seasons,” and every month or so we reconvene to debrief what we’ve experienced. The students publish short-form exhibition reviews to a public website, which I edit to within an inch of their lives, flagging everything—syntax, lexical choices, infelicitous phrasings, etc.—that separates their drafts from what I have experienced as publishable art criticism. Other students offer comments, the reviews are revised, and then we hold writing workshops to further polish the work. Because we are a community of art spectators visiting the same galleries, we are uniquely suited to assist each other in how we observe and experience the shows we see together. Sometimes I share drafts of particularly disastrous or successful editorial experiences I’ve had or am having to encourage the students to loosen up about receiving feedback on their work. I appreciate short-form art criticism for its haiku-like brevity and ability to encapsulate complex spatial and semantic experiences in two or so paragraphs. Not to be gonzo, but even in a few paragraphs you can hook the reader while also giving them a sense of the stakes—why care about this show, this piece of writing?

10. What advice do you give to your students as they leave school and enter the field?

When I was about twenty years old and stressed about how impossible it seemed to make a career as an art historian, given the confusing politics of my very own department, Jerry Karabel offered me the following words: “It’s all about doing good work.” He was right, of course.

If you do it long enough, if you work hard and develop a practice as a writer, as an artist, you can then use that strong voice to help others in their efforts. That just might make you a happy person, and you may also feel great power within yourself and in your community.

Speaking for myself, my twenties were quite financially difficult and confounding: it isn’t easy trying to make a living when you’re from an impecunious background and are living in an expensive place like New York City, with its many invisible rules about how to succeed. The drudgery of sacrifice is hard, and precarity can come to feel a personal burden rather than a collective problem of how people who pursue noncapitalist goals are treated as disposable populations. As in any field there are ingénues, and, I suppose, today also “influencers.” Comparing oneself to others’ successes is a fantastic way to feel inadequate. There’s a lot of structural negativity out there encouraging competition and dissatisfaction, scarcity and resentment. But that’s not the way it has to be.