1. Why did you decide to go into teaching?

I first came to teaching in 2003 as a PhD student in visual cultures at Goldsmiths. There I had my first experiences with experimental, collaborative, and exploratory modes of teaching, facilitating group projects in which students shaped their own curricula and forms of creative presentation. One transformative moment came in an introductory art history seminar: I asked students to make their own maps of art history, and one student made a drawing of an underwater scene. “Friendly” art movements, such as impressionism, were at the surface, represented by dolphins and turtles. Further down were more predatory creatures, like a shark who represented cubism. A large rock on the sea bed was the Renaissance, and behind that was a “feminist art” sea monster. The student could articulate her anxieties about her subject in a manner that expressed how all our histories are layered in complex, affective, and nonlinear ways. By the end of the term, she was writing essays about feminism. Finding that I could contribute to that kind of growth inspired me to teach.

2. What drew you to your school and what is your teaching philosophy?

Goldsmiths has offered me a context in which to engage with artists who address the urgencies of the present, with all its complicated inheritances, and to imagine alternatives in incredibly diverse ways. It’s been exciting to see the important work that has emerged at Goldsmiths in recent years involving creative and critical anti-colonial, feminist, and queer approaches to ecology and environmental justice, particularly the work of researchers and artists in the Critical Ecologies research stream.

For me, this has entailed linking theory and academic inquiry with practical engagements to create spaces for ecological care and artistic research, such as the Art Research Garden, of which I’ve led the development. My approach to teaching is aligned with the art department’s focus on student-centered learning—I want to find out the driving questions and singular passions that artists bring to the materials, stories, sites, and issues they are situated in. At the same time, when working with groups of students it is vital to build a common ground, whether through a set of mutually agreed upon approaches or texts and artworks that we can engage with collectively. In my teaching, I seek to foster values of mutual respect, critical rigor, and creative curiosity to enable inclusive and transformative learning experiences. I believe that art-making works best as a question to the world, suggesting a new conjuncture or way of seeing, rather than necessarily providing solutions.

3. What theory and art history do you consider most essential for your students? What artist or artwork do you refer to most often?

I try to ensure that curricula and teaching formats are supportive and emancipatory, centering anti-racist, anti-colonial, feminist, LGBTQ+, and neurodiverse perspectives and drawing attention to structures of power at work within epistemes that may be most powerful when they are invisible. While the MA Art & Ecology students’ own artistic research drives much of their theoretical and practical work, I teach a course of lecture-seminars called “Histories and Theories of Art & Ecology” that is designed to give them a strong and broad grounding in the most essential ideas and practices that they need to know about to navigate this expanded and fast-evolving field with confidence.

I constantly update and revise my teaching materials, but there are many artists and theorists who I have returned to time and again in recent years: Otobong Nkanga’s powerful embodied explorations of material histories, Jumana Manna’s magical films relating culture and cultivation, the Otolith Group’s insistence on a cosmopolitics rooted in Black radicalism, Susana de Sousa Dias’s investigation of the haunted moving image archives of colonial fascism, Sakiya’s rewilding of pedagogy and vital rethinking of nomadic land stewardship in Palestine, Renée Green’s poetic time-space crossings, Ursula Biemann’s engagement with the rights of nature and indigenous worldviews, Karrabing Film Collective’s expression of their relations to land under settler colonialism, Max Liboiron’s insights into pollution as colonialism, Elaine Gan’s multispecies mappings, Heather Davis’s necessary thinking around plastic inheritances, Susan Schuppli’s work on material witness, Jol Thoms’s explorations of environments and experimental physics, Gerard Ortin’s agrilogistics, FRAUD’s investigations into extractivism, Åsa Sonjasdotter’s tracing of marginalized regenerative agricultural practices, Barby Asante’s approach to decolonial strategy, and Sigrid Holmwood’s multifaceted artistic investigation of the commons via pigment-making. The tentacular queer feminist thinking of Donna Haraway is woven throughout my teaching, as are Anna Tsing’s stories of Anthropocene entanglements and Ursula K Le Guin’s profoundly ecological fantasy writing. I deeply appreciate Malcolm Ferdinand and Françoise Vergès’s approaches to decolonial ecology, particularly their refusal of collapsology narratives. In terms of queer theory, Jack Halberstam’s notion of wildness and Catriona Sandilands’s genealogies of queer ecology have been particularly important. I find Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s marine mammal emergent strategy compelling. In terms of writings about the coloniality of the garden, Jamaica Kincaid and Jill H. Casid have been crucial, and I frequently reference Carole Wright’s Blak Outside work. Reuben and Maja Fowkes and curator Bori Soos are doing crucial work understanding ecology and challenging ecofacism in Eastern Europe. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Jennifer Gabrys have been formative to my understanding of planetarity. T. J. Demos’s critical approach to decolonizing nature, Maria Puig de la Bellacasa’s understandings of the multiple nonlinear times of soil care, and Shela Sheikh’s work on more-than-human witnessing and testimony are essential.

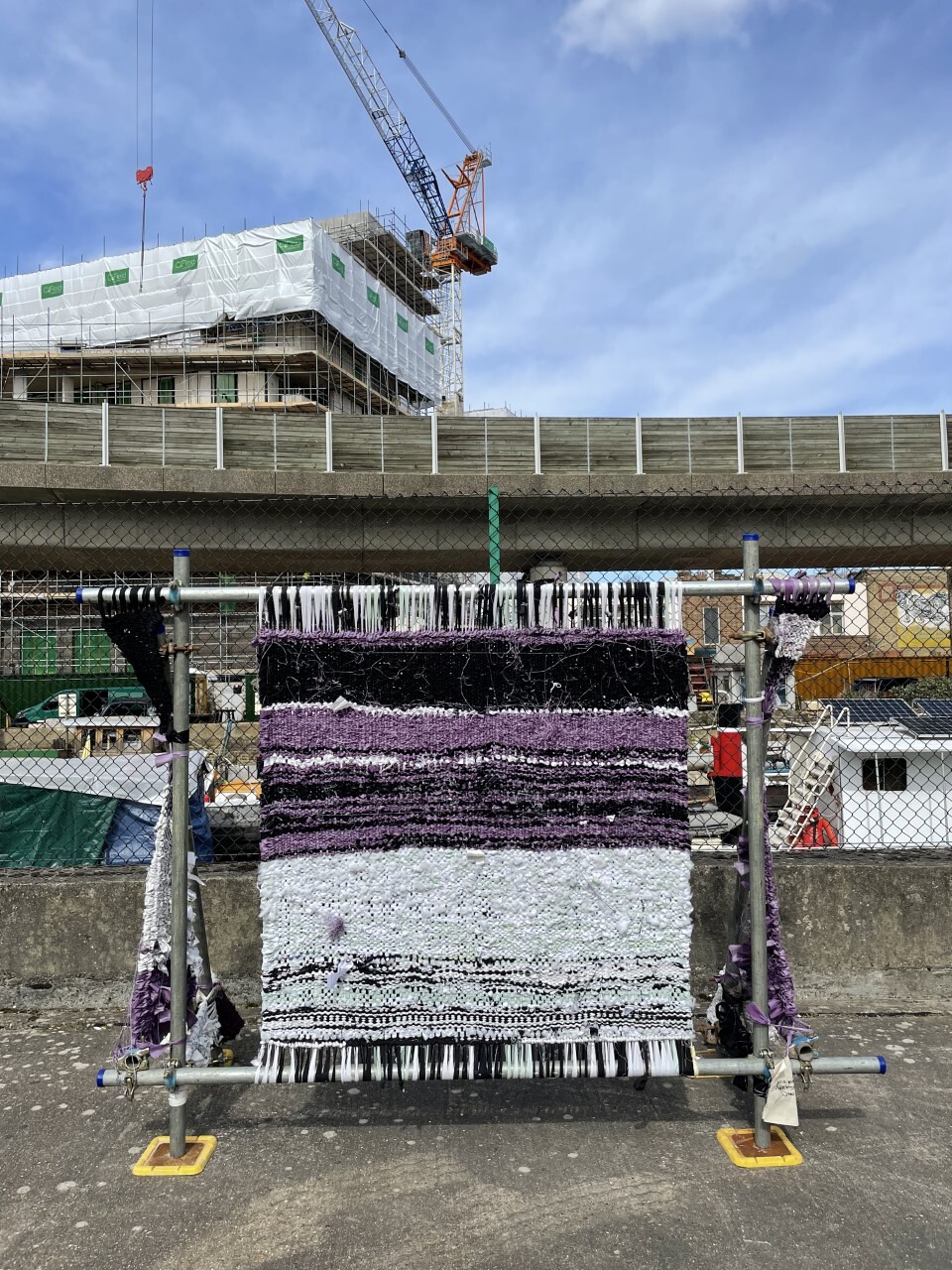

Laura Buckle, Interwoven, 2022. Scaffolding, recycled textiles, care labels, Portsmouth sand. Installation view, MA Art & Ecology Interim Show. Photo: Jol Thoms.

4. How do you navigate generational or cultural differences between you and your students?

More than anything, I try to listen and live up to the guidance that we impart to our students when they enter the space of the crit or seminar: we are all learners, and we all deserve respect. Demonstrating compassion and a willingness to call out injustice are both essential. Teaching offers constant reminders that it is important not to be complacent about what we know. In recent years, I have gained much from thinking about how I am situated in relation to power, and that is ongoing work. There is no turning back from the achievements of #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, trans activism, and advocacy around invisible disabilities. I deeply appreciate the growing openness around mental health and the need to recognize the importance of different kinds of care.

5. What changes would you like to see in art education?

I would like to see greater financial and practical support for our students to make their studies more manageable and, more broadly, a much greater appreciation of the vital role that artists play in society. I am keen to develop and nurture relationships with external partners to provide professional and educational opportunities for our students and to make our art institutions more accessible. There is a lot more work to do in terms of addressing questions of equality and representation in art education at all levels. I want to contribute to that, and I recognize that there may be times when that involves stepping up and times when I, as a white middle-class English woman, should step back. In the context of climate crisis and ecological breakdown, we all need to be working far more radically towards more sustainable and nurturing ways of doing.

6. What is your educational background? Did you arrive at art from another field?

I was a constant maker and reader as a young person, and I studied English literature at Oxford University. To do a degree that involved reading two or three novels a week felt like an incredible luxury. It was a very traditional education—from Beowolf to Virginia Woolf—but it gave me my first taste of theory. Reading Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble and other feminist writers for the first time was electrifying. After a few years working in art book publishing at Thames & Hudson and Phaidon, I hankered to equip myself with a better understanding of contemporary visual culture and theory, particularly in relation to feminism and postcolonial theory. The MA in Cultural Studies at Goldsmiths, then only in its second year, was ideal as it provided pathways away from my Eurocentric educational background, and my PhD in Visual Cultures with Professor Irit Rogoff and Kodwo Eshun, in which I researched militant filmmaking affiliated with the late twentieth-century African revolutions, developed from that and led to numerous collaborations with artists and curators, such as the Otolith Group, Anna Collin, and Grant Watson. I have always been an eclectic thinker with many interests, and so when I started teaching in the art department, the freedom with which art students tend to approach theory and visual culture resonated with me.

7. How have recent cultural movements and activism informed your curriculum?

The MA Art & Ecology seeks to support artists engaging with pressing environmental issues, which are necessarily also questions of social justice. Recent cultural movements and activism thus strongly inform our curriculum and the conversations we have with students in the studio. However, we also seek to provide students with a broader and deeper grounding in the longer genealogies of the present and challenge the gatekeeping around who gets to speak for the environment. It is vital to understand how, for example, the ideology of extractivism emerged in relation to the suppression of women and the commons, how the notion of species coevolved with scientific justifications of racism and ecofascism, and how wildlife conservation practices were a crucial part of colonial projects and ongoing forms of colonialism.

8. How much structure or independence do students have in your courses?

When applying to the MA Art & Ecology, students apply with a “project” that they develop over the course of the entire fifteen months, so we look for applicants with creativity, openness to change and development, and independence of thought. This means that the program is suited to artists who have developed their artistic practice sufficiently for postgraduate study and are committed to working within the field of art and ecology—which in fact means an incredibly diverse array of interests and approaches! Our students have fed back to us that they feel well supported by the structure of the program, which involves many opportunities for feedback. While the crits, seminars, and lectures are strongly structured, they are led by students’ interests and concerns. The program is designed to guide students toward increasingly independent research, thus providing an excellent preparation for those who are interested in pursuing a PhD.

9. How does the program connect students to the surrounding art scene? How do they learn outside the classroom?

At the beginning of the program, our students take part in an experimental laboratory led by an artist that may involve artistic research on a site of ecological interest. We encourage our students to engage broadly with the local art scene in Deptford and New Cross, and we use study trips to introduce them to art institutions and sites that they might not otherwise encounter.

Throughout the MA Art & Ecology there are ad hoc opportunities for our students to take part in projects that may involve engagement with local schools or external partners. At present, a group of our students is undertaking a public commission with the Horniman Museum and Gardens in South London that involves working with local school children to produce a series of billboards that address climate change through an engagement with the museum’s collection and gardens.

The art department recently launched an exhibitions hub that supports public-facing exhibitions by students and alumni. As well as providing practical support, it is building partnerships with galleries and other organizations both local to Goldsmiths and further afield. The Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) at Goldsmiths hosts world-class exhibitions and commissions new works from international artists alongside emerging artists, including graduates from our own programs. It also supports grassroots networks of artists and activists engaging with local issues.

The Art Research Garden is another site of engagement that our students benefit from that is being developed to support ecological artistic research as a site for cultivation, knowledge sharing, performance, and urban rewilding. At present, the Art Research Garden is hosting Harun Morrison as its first artist-in-residence. He is working with soil scientist Dr. Jacqueline Hannam and the Lewisham Migrant and Refugee Network on a Creative Climate partnership with Goldsmiths funded by the Natural Environment Research Council that explores how soil care might mitigate local and global climate change impacts.

10. What advice do you give to your students as they leave school and enter the field?

Throughout the MA Art & Ecology, we encourage our students to develop forms of mutual support and to try out collaborations that may help to sustain their practice in the future. In the second half of the program we provide professional practice workshops by artists, curators, and activists that are based on real-life experiences of how to approach opportunities that are relevant to the field of art and ecology. The networks they form during the MA are often crucial to organizing their first exhibitions and studio spaces after art school. We are also delighted about the new CIRCA MA Art & Ecology scholarship launching this year, which provides financial support of fifteen thousand pounds to a student from a nontraditional academic background.