1. Why did you decide to go into teaching?

None of my art history professors looked like me. No one in my family pursued art history as a career path. Until college, the only “art” museums I visited were the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and National Air and Space Museum along with and the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum. The Mellon-Mays Undergraduate Fellowship provided me with the first opportunity to even consider teaching in art history as a career. While completing my dissertation, my alma mater Williams College invited me to teach an African art history course that I felt was missing from the curriculum when I was an undergraduate. Since then, I have felt that the fields of art history and visual culture require a diversity of people and perspectives. Teaching is my way of addressing this need.

2. What drew you to your school and what is your teaching philosophy?

The Bard Graduate Center understands the importance of visual and material culture and is committed to showcasing diverse perspectives. We have a range of disciplinary interests that don’t fall neatly into departments. The institution has identified African and African Diaspora material culture as a key curricular and programmatic area. At present, I’m organizing workshops, symposiums, and exhibitions geared to addressing the following two questions: “What is Black material culture?” and “What does it mean to center Blackness in the study of material culture?” I couldn’t do this type of work in a disciplinary-oriented setting.

Teaching is a critical part of my research process as a writer and curator. As a professor, I don’t have all the answers. I see my role as facilitator. I encourage my students to ask questions, even when they lead to more questions. I come to class to learn from my students, and they always know about cool artists and arts movements that I haven’t heard of.

3. What theory and art history do you consider most essential for your students? What artists or artwork do you refer to most often?

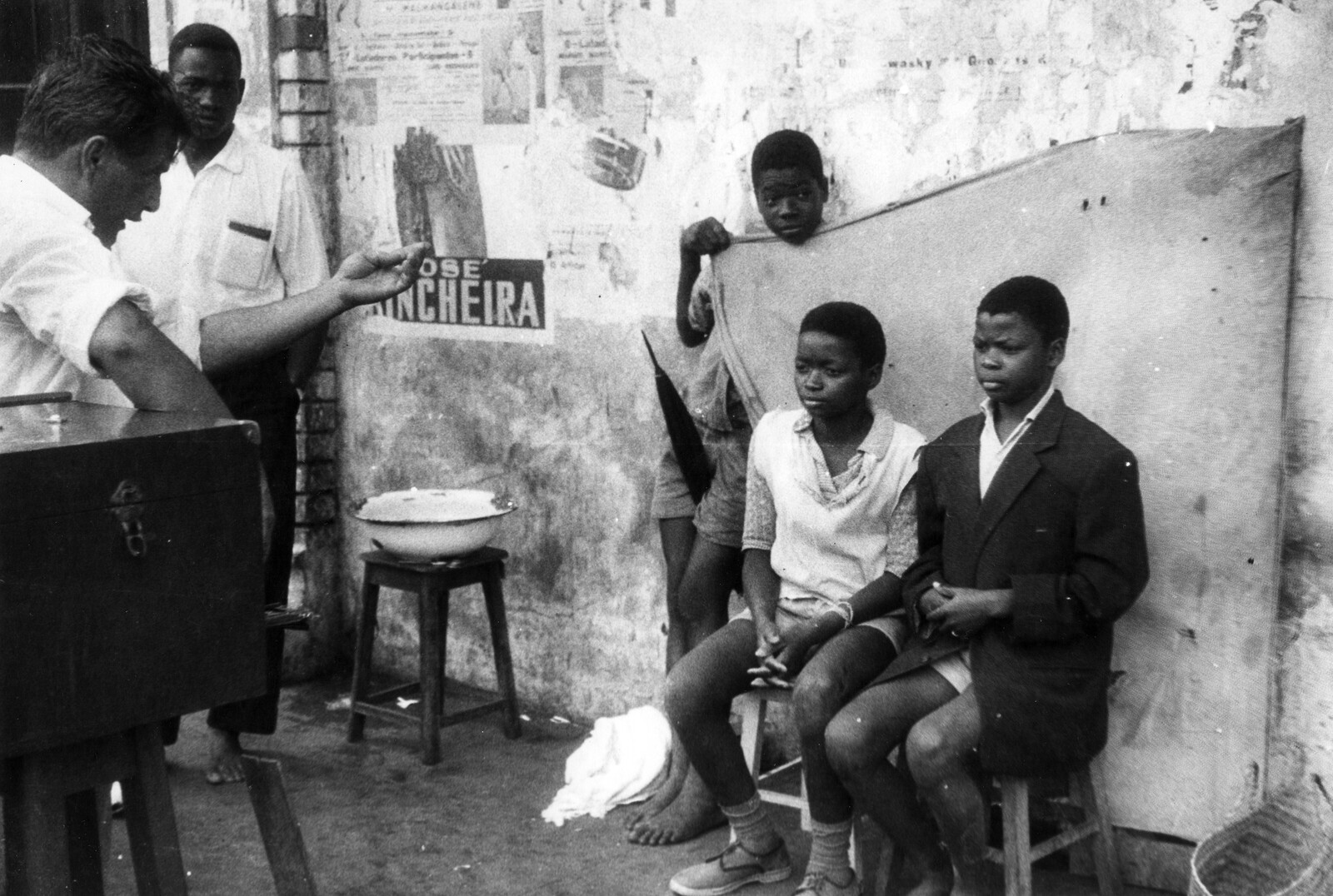

Essential are the writings of Leigh Raiford, Nicole Fleetwood, Édouard Glissant, and Krista Thompson on African-American and Black Diaspora art history. There is the need to bridge the fields of African-American and African art history and visual culture. Additionally, current writings on photography prioritize theory over historical context and specificity. I address this gap in my most recent book, Filtering Histories: The Photographic Bureaucracy in Mozambique, which offers a history of photography in Mozambique.

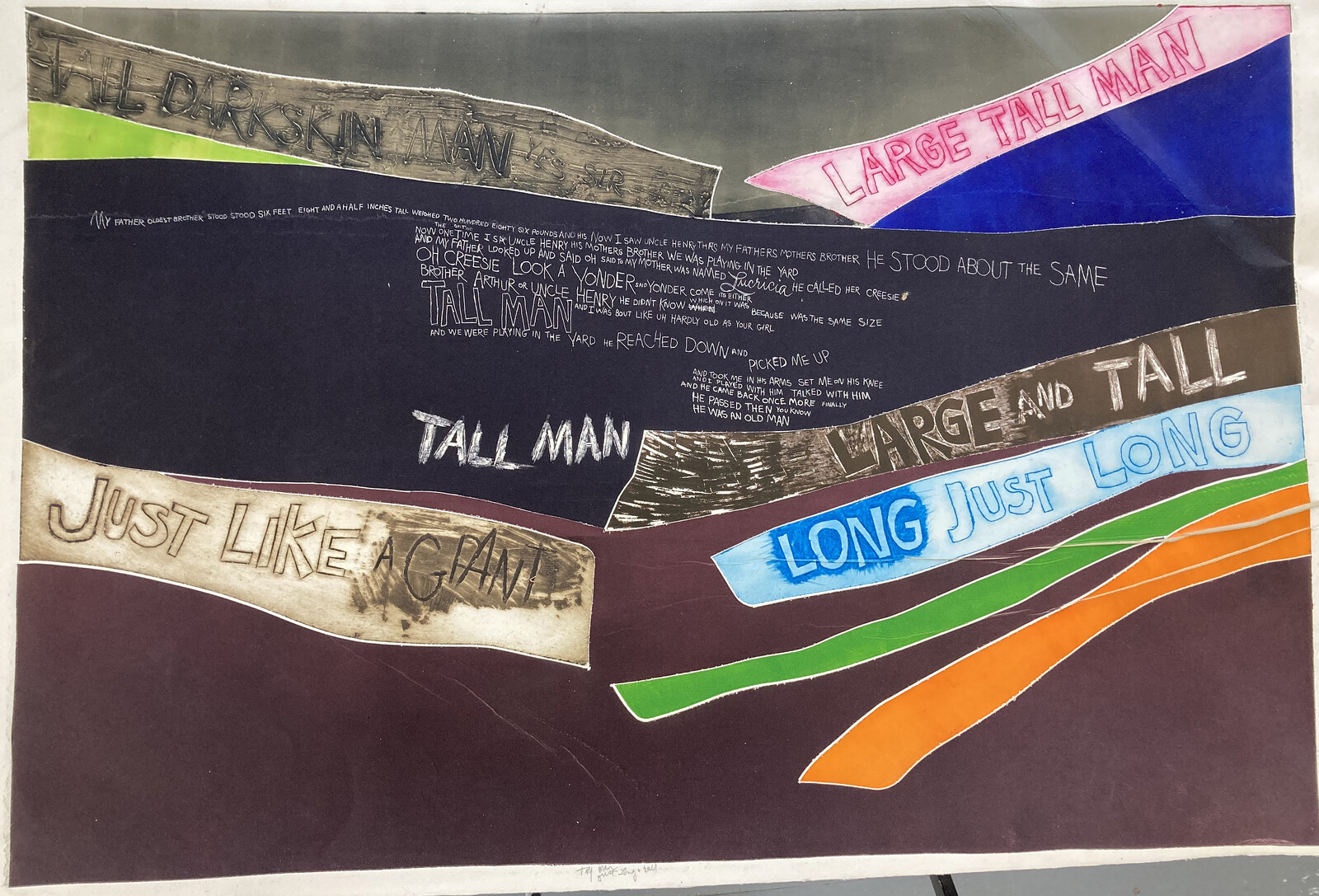

On the first day of classes, I usually show Arthur Jafa’s Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death and Flying Lotus’s “Never Catch Me ft. Kendrick Lamar.” My courses on Black modernism, modernism in art history, and the history of photography in Africa reference artists ranging from Black Americans Hale Woodruff and Augusta Savage to Mozambicans Ricardo Rangel and Ângela Ferreira.

4. How do you navigate generational or culture differences between you and your students?

Watching Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death forces my students and I to confront our own biases and how images condition us to see the world. I want my students to question why they have or have not been attentive to images of police brutality and Black celebration. Attuning to the power of images and image-making practices allows us to identify our differences and to develop a language that is attentive to the presented subject materials and each other.

5. What changes would you like to see in art education?

Naturally, I would like to see more courses and career opportunities in African and Black Diaspora arts and material culture. Beyond that, I would like to see a more nimble, inclusive, and expansive definition of arts education. To that point, I draw inspiration and guidance from the efforts of Black American artists like Benny Andrews, Betty Blayton, and Benjamin Wigfall, all of whom developed extraordinary community arts initiatives to reach young and incarcerated people who were excluded from art education.

6. What is your educational background? Did you arrive at art from another field?

I trained in art history and history in the early 2000s and found art history to be alienating and exclusionary. Financial reasons prevented me from pursuing a career as a museum professional. Enrolling in a PhD in African history was a more viable and welcoming option for me, but I quickly found African history to be a white male-dominated field that minimized the visual arts, material culture, and Black American historical perspectives. Since finishing graduate school, I more readily identify as a visual historian with interests in modern and contemporary African and Black Diaspora visual and material culture.

7. How have recent cultural movements and activism informed your curriculum?

Questions of police brutality and social inequity are not new to the fields I research and teach. Scholars and activists of African and African-American Studies have long studied these areas from the margins of their respective disciplines. In fact, academic programs like African and African-American Studies developed explicitly out of the need to address the marginalization of African, Caribbean, and Black American histories and culture within academia and to find a path forward for a more just and equitable future. Mainstream art institutions are just playing catch-up.

8. How much structure or independence do students have in your course?

I’m currently teaching a course on African-American, African, and Black Diaspora material culture. I lean on historical chronology to structure my courses. I introduce students to when and how the subject matter developed into a scholarly field. Additionally, I illustrate how different material and artistic practices, like photographic portraiture, unfold over time and across geographical locations. Writing assignments, which range from exhibition reviews to object analyses, provide opportunities to translate presented course materials into their own areas of interests, which often include the decorative arts, design, and fashion.

9. How does the program connect students to the surrounding art scene? How do they learn outside the classroom?

It is important to model for students how artists, writers, and professors (to name a few elements of art education) develop their ideas, or what James Baldwin called “the creative process.” To this end, I’ve developed the programmatic platform “Creative Process in Dialogue: Art and the Public Today.” Invited participants, who have included Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, and Bradford Young, have discussed their creative processes and commitments to the humanities. The public conversation diversifies perspectives on arts disciplines and offers models for collective and inclusive dialogue.

Additionally, I think of the gallery space as an extension of the classroom. Certain questions are best considered through exhibition making. BGC features a vibrant gallery with a visionary curatorial team, and in the coming months, my students and I will curate an exhibition of modern and contemporary African visual and material culture that will open in 2023 alongside an exhibition on African metalwork.

10. What advice to you give to your students as they leave school and enter the field?

I had unsupportive graduate school advisors. I experienced firsthand how they advocated openly for their preferred candidates. And we know how this type of favoritism impacts funding, publication opportunities, and job prospects. Mentorship and a close community of friends, family, and colleagues have helped me to be resourceful and imaginative. I am still learning how NOT to compare myself to others. As Jay-Z said, “I can’t base what I’m gonna be off of what everybody isn’t.” Mindful of how I felt in graduate school, I always tell my students to find mentors and collaborators who can offer candid career advice, always-needed encouragement, and generative feedback. Also, I encourage students to find new opportunities where they can be experimental, exploratory, and nurture their interests in unanticipated ways.