1. Why did you decide to go into teaching?

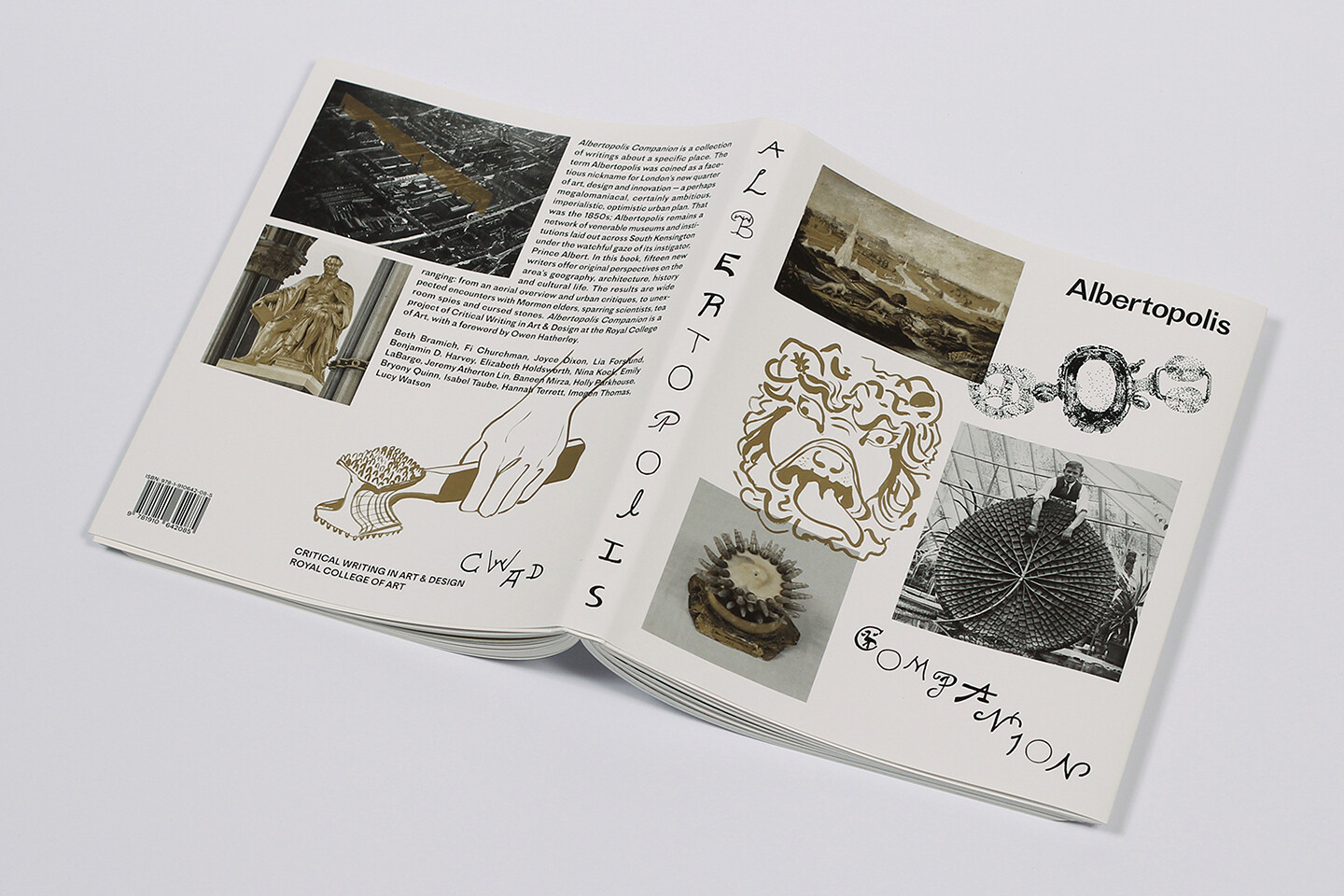

It was an accident! I was lucky to encounter teaching opportunities while I was doing my PhD: I worked with the second-year MA Writing students on their annual collaborative project, which was to make a book. I loved the format of this project. It was so open, based around ongoing conversations, brainstorming, group crits of concepts and pieces of writing. It also involved problem-solving both intellectual and practical—devising the publication from content to form, its graphic design, printing, and distribution, and launch events. It was more like working alongside and with the students than instructing them: I was there as a mentor or a guide to help them make decisions on their own, not as someone to dictate hierarchically or intervene from above. This has remained my approach as a teacher.

Once my thesis was finished, I continued teaching in various capacities—because I enjoyed it and because I needed the work. At the Royal College of Art, like many other art schools, a lot of the staff are part-time because they have parallel lives as practitioners in art, design, architecture, etc. This external work is vital and feeds into the teaching that you do, and vice versa. I’m often surprised, enriched, and heartened by exchanges with my students. It keeps me thinking and learning too.

2. What drew you to your school and what is your teaching philosophy?

The MA Writing program at the RCA is the only one of its kind in the United Kingdom. We combine a deep interest in literature with an investment in art, criticism, fiction and nonfiction, and experimental and interdisciplinary work. We’re interested in thinking about the place of culture in the wider world and the place of art in relation to other disciplines. Most of all, our focus is on writing as a practice—as a form and a medium on its own terms, with many different outcomes. This has always been exciting to me, and an art school is uniquely suited to this kind of study.

My teaching philosophy is loose, constantly changing, and non-prescriptive. I believe what bell hooks wrote in Teaching to Transform:

The classroom remains the most radical space of possibility in the academy … As a classroom community, our capacity to generate excitement is deeply affected by our interest in one another, in hearing one another’s voices, in recognizing another’s presence … Engaged pedagogy does not seek simply to empower students. Any classroom that employs a holistic model of learning will also be a place where teachers grow, and are empowered by process. 1

The classroom is not mine, it belongs to everyone in it. I want to give students enough space so that, as a teacher, I become invisible; that the room is purged of the categories and forms of valuation to which institutions and institutionalization are so wedded; that others might lead and I follow.

3. What theory and art history do you consider most essential for your students? What artist or artwork do you refer to most often?

We don’t have a fixed syllabus or canon. Readings vary from year to year, tailored to the different writing briefs we set. We often focus on texts in order to think about different qualities of writing—style, form, voice, description, argument, and so on—rather than theory or art history proper (though these all, of course, intersect and overlap). Every autumn, however, I give my students Adorno’s “The Essay as Form,” and they are not always happy about it! 2 But they come around. It’s a challenging but vital and sublime text about—among other things—resisting totalizing thought and reification, refusing answers and end points, categories and lineages. It’s about not accepting what you’ve been given and what you’re told is naturally occurring or “the way things are.” This includes what writing should sound like or do, what art should look like or aspire to, what knowledge is, how thought works. This is essential for any writer because thinking about how to be a writer is also thinking about how to be a person in the world.

Among other lodestars, too many to count: Wayne Koestenbaum, Lynne Tillman, Trinh T. Minh Ha, Hilton Als, Cathy Park Hong, Adrian Piper, Moyra Davey, Elizabeth Hardwick, T. J. Clark, Anne Boyer, Lorraine O’Grady, Etel Adnan, Anne Carson, David Rimanelli, Janet Malcolm, Saidiya Hartman, Joan Didion, Jamaica Kincaid, Jenny Diski, Maeve Brennan, Cecilia Vicuña, Margo Jefferson, Gloria E. Anzaldúa …

4. How do you navigate generational or cultural differences between you and your students?

With solidarity, curiosity, and generosity. I have no assumptions about what I may or may not have in common with someone else in the room; what I can or cannot learn from them; nor that we are divided or categorized only according to certain differences and similarities. Age and culture are two of many axes within a person, and of course the students also encounter these and other differences among themselves. Education is conversation.

5. What changes would you like to see in art education?

Art education, like all forms of education, should be free. Universities should employ fair labor practices at every level of the institution, from the ground up, including service staff who are now usually outsourced. Arts and humanities should not be policed by the government. The outcome of education is first and foremost to learn and to think, not to “enter the workforce” or to become a “productive part of the economy.” This is a bad metric, which is really about restricting who is allowed to be educated in the first place, and it should be abolished. Art education should not be a commodity available solely to those able to purchase it. Students should be encouraged to refuse this mentality.

6. What is your educational background? Did you arrive at art from another field?

I have always moved between literary and art-historical studies. I did a BA double major in English literature and art history; an MA in modern and contemporary art studies; and a PhD in critical writing in art and design, during which I became a writer. I guess I couldn’t decide between the two disciplines, which turned out to be a good thing. My education has also been split between Canada and the UK—or Europe, as I still insist we call it.

7. How have recent cultural movements and activism informed your curriculum?

My views are socialist feminist—as in, revolution in the service of every living thing—and the curriculum I organize probably reflects this, though not always explicitly. Politics, culture, and activism have so many different iterations in writing and art—direct, oblique, formal, material, theoretical, etc.—as varied as their makers, which is a good thing. Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about writers we’ve lost, whose work laid the foundation for so much important current thinking: bell hooks, Nawal El Saadawi, Lauren Berlant, Leo Bersani, and others. These are writers whose work is not just about articulating politics but enacting them: theory and praxis. There’s rarely enough of the latter in academia, and both should be taught—especially to those who are essentially practitioners.

We also need to talk about class. I’m hoping the next popular cultural movement will be socialism! What is writing (for) the collective or writing (for) the commons? I want the students to recognize and learn that recent cultural movements and forms of activism have precedents and long histories. It’s convenient for some if these are erased and forgotten, but legacies of collaborative struggle are real and important. I also encourage the students to define “urgency”—a word we hear often now—on their own terms. Art and writing can do a lot of things, but alone they are not blunt tools to solve social, cultural, or economic inequality.

8. How much structure or independence do students have in your courses?

About half and half. Each week there are scheduled classes: reading seminars, workshops, guest speakers, tutorials, and group crits of ongoing student work. The briefs we set for different projects are very open, however, and the students can write about whatever or whomever they want, and however they want—part of making these decisions is being able to articulate and argue for them. Writing and research is primarily self-guided, and we encourage the development of a daily independent writing practice that is undirected and freeform: writing is a form of thinking, it takes you places you might not get to otherwise. Classes are more facilitated than led by the program staff: we like the students to take initiative, to bring their own questions, ideas, readings, arguments and counterarguments. In group crits, the students are very actively involved in close readings of the work of their peers, and they lead the conversation, which is discursive rather than evaluative.

9. How does the program connect students to the surrounding art scene? How do they learn outside the classroom?

We have an active public program, including talks by recent alumni, guest speakers, symposia, and conferences with contributors from across disciplines. These are open to all RCA students as well as the public, and we often get a big, diverse turnout. In past years, these have included events on “The Essay,” “AUTO” (auto-fiction, -theory, -ethnography, etc.!), “WHERE’S SARDINES? — Art + Poetry,” “Performance and Writing,” with incredible speakers including Wayne Koestenbaum, Lynne Tillman, Susan Howe, Anne Boyer, Deborah Levy, Lavinia Greenlaw, Quinn Latimer, Max Porter, Vahni Capildeo, Juliet Jacques, Catherine Damman, Kayo Chingonyi, Brian Dillon, Moyra Davey, Claire-Louise Bennett, and others. We organize these annual events around themes or issues that come up in discussions with our students as a way of interrogating ideas on a larger scale and in connection with professionals and practitioners at different levels. Ideally, this allows the students to see how they exist on a continuum that extends beyond the institution while also exposing them to new people and ideas.

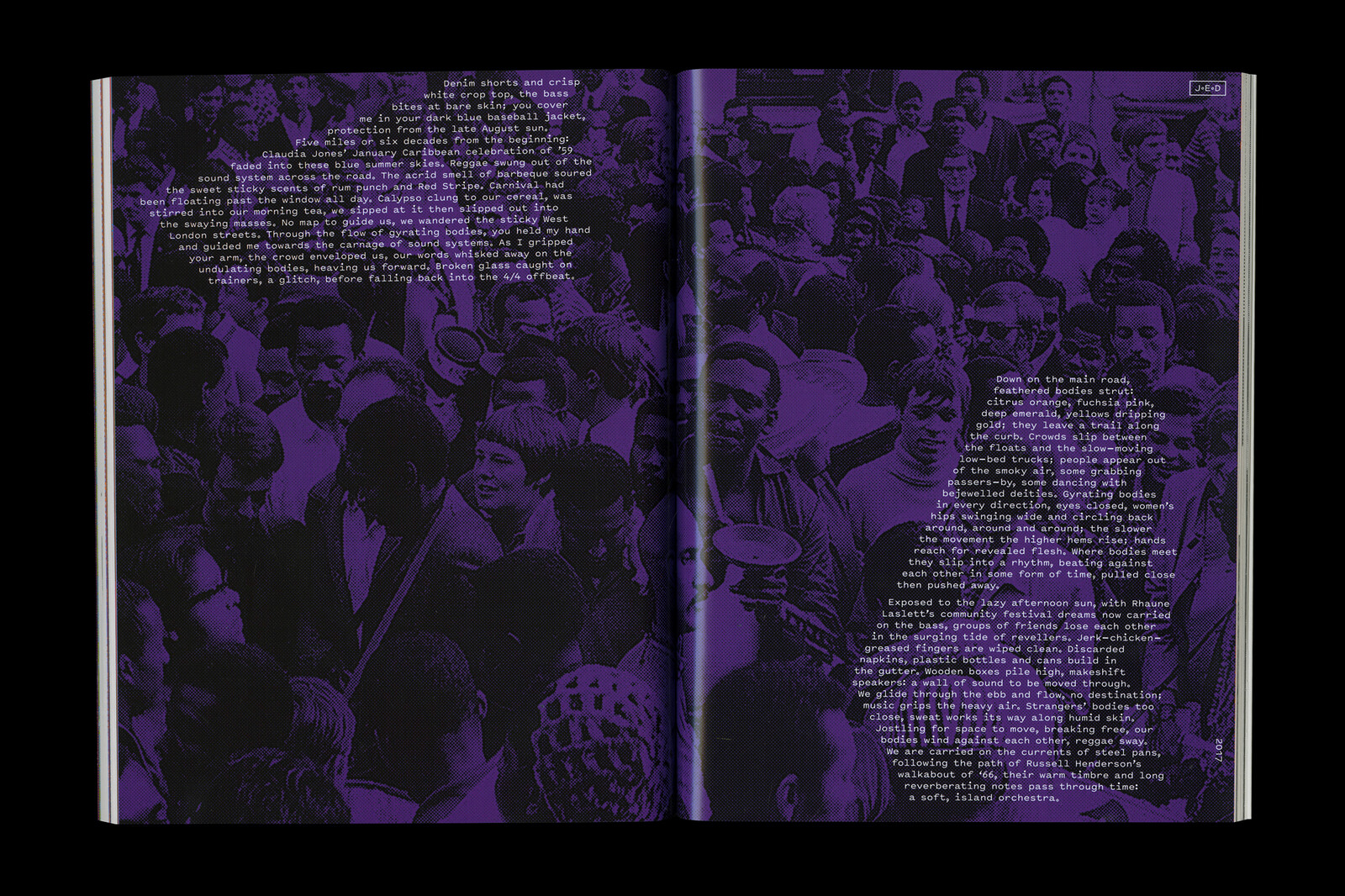

Every year also involves a project with an external partner in the UK, for which the students produce a body of work in response to the host. The outcomes are as varied as the external partners, which have included Siobhan Davies Dance, the Museum of London, the Swedenborg Society, Flat Time House, the Warburg Institute, CAST Cornwall, and Turner Contemporary, among others. Additionally, the collaborative publication project connects the students with people outside the college: they print their book out-of-house, so must engage with the printing industry and all its practicalities, from paper stock to wet proofs to binding variations and delivery schedules. They also launch their work at an external venue—often a bookstore or an art space—which they take the initiative to organize with support from us. We’re keen for them to gain practical as well as intellectual experience. Last year, the students organized a daylong symposium around their publication, which involved inviting students from international art schools—School of Visual Arts in New York, Glasgow School of Art, and Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam—to present work in response.

10. What advice do you give to your students as they leave school and enter the field?

Writing is hard! Keep at it, keep developing your practice, which is something that will continue to change and evolve throughout your whole life: you’re just at the beginning, you don’t know what you don’t know. Write every day, even if it’s just for thirty minutes and to no end. See and read as much as you can. Keep pitching, don’t get discouraged, don’t take rejections personally. Believe in what you’re doing, and if you can’t find a place for it, make one yourself, collaborate with others—there are so many ways to put your work into the world, and many publications and contexts that don’t yet exist. Have faith in a curious audience. Learn to love your editors. Cultivate a community.

bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as a Practice of Freedom (New York, London: Routledge, 1994), 8–21.

Theodor Adorno, trans. Bob Hullot-Kentor and Frederic Will, “The Essay as Form,” New German Critique, no. 32 (Spring–Summer 1984): 151–71.