http://www.cafa.edu.cn/

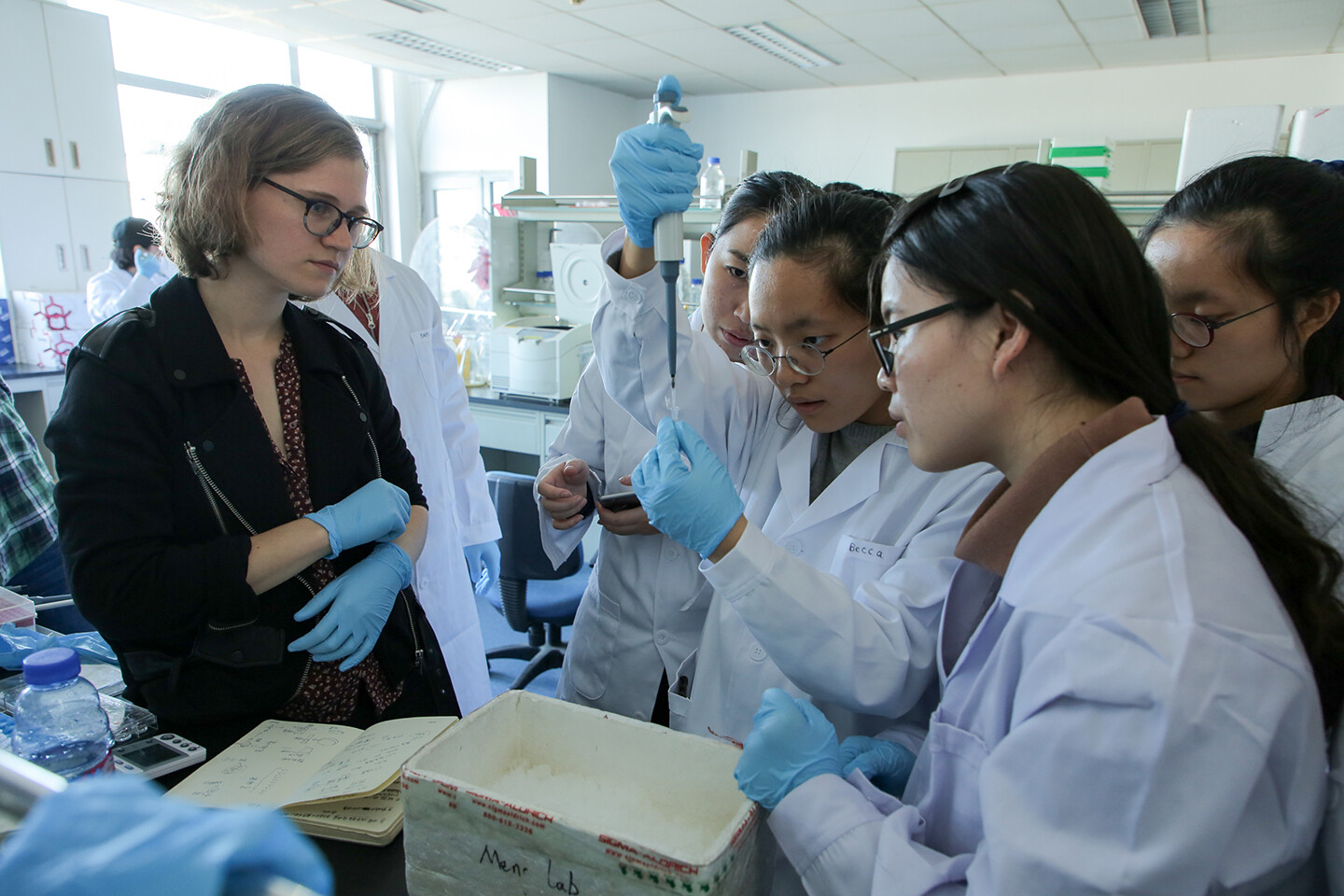

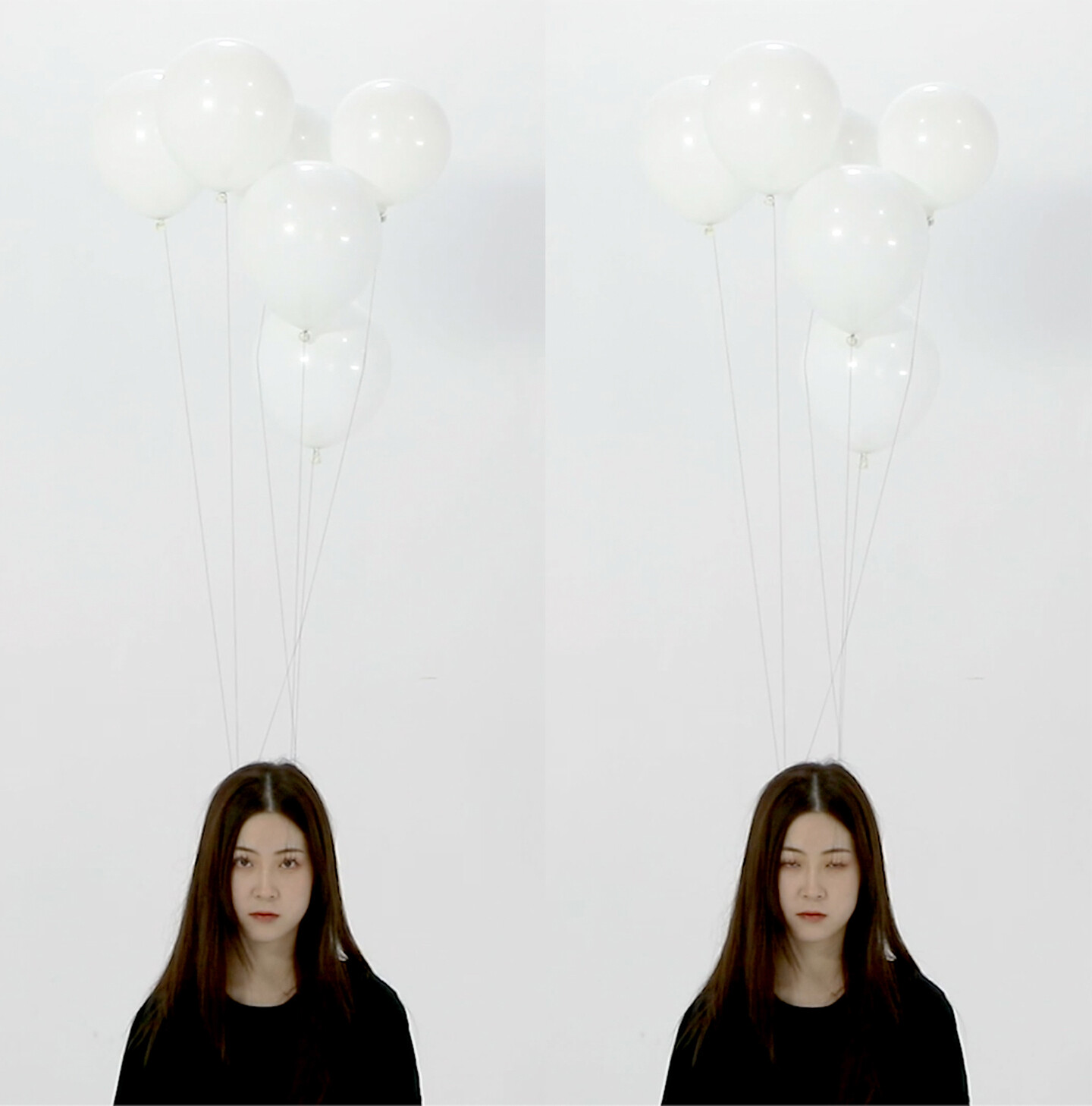

The annual graduation exhibition at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) is a marquee event for the Beijing art world. The diversity of works on view not only compose the rich polyphony of CAFA’s graduate programs but demonstrate the cutting-edge topics that animate the artists’ practices. This year, with more than four hundred graduate students from all CAFA departments featured, “READY TO-GO” offered intensive engagement with over three thousand artworks ranging from painting, installation, and sculpture to design, architecture, and projects in experimental art. Among this immense amount of material and information on display, viewers encountered a young female graduate student sitting on a wooden chair, expressionless despite being surrounded by the buzz of an audience and their probing cameras. Barely visible to the naked eye, threads as thin as cicadas’ wings were attached to her eyelashes, and each time she blinked, this subtle act tugged at the threads and the translucent white balloons tied to them. An eyelash falls once every three thousand blinks, and batting her eyes against currents of air created by the crowd around her, the artist maintained her composure as balloons drifted into the exhibition hall. He Xuan’s performance Mental Activity in Full View of the Public contrasted the artist’s machine-like, emotionless control with the balloons’ tendency to float freely and the crowd’s unpredictable frenzy, a visualization of the push and pull between technology and art that characterized He’s time in CAFA’s School of Experimental Art.

He researched and developed her work in the school’s “Total Art and Interdisciplinary Studies” research program. During her three years of study, she worked with performance, computer vision, machine learning, and brain-computer interface devices. During field research designed by the school’s master’s faculty, He was embedded in the cardiology department at the China–Japan Friendship Hospital, where she encountered contrast media employed in cardiac imaging, techniques and equipment used in common medical procedures, and a seldom-seen disease called “broken heart syndrome.” These innovations in healthcare technology and evidence of emotional fragility, as well as the social bonds between doctors and patients that she witnessed, all inspired Mental Activity in Full View of the Public and her final projects. “Some people felt the pain and suffering imposed on my eyelashes, some of them tried to cut off the threads and disrupt the performance, some attempted to encourage me, and later on, I saw my performance all over social media,” He said. Her work in the graduation show served as both a demonstration and continuation of her research on trauma and the relationship between bodies immersed in contemporary technologies and healing practices.

He Xuan, Mental Activity in Full View of the Public, 2021. Installation view, CAFA Art Museum, Beijing. © Central Academy of Fine Arts.

Next to her performance at “READY TO-GO,” He presented a rope-skipping device controlled by eyeball movements, a project observers might easily file under the genre of “art and technology.” Such a categorization, however, oversimplifies the school’s mission: the School of Experimental Art seeks to be a catalyst for cross-disciplinary research and practice not defined by mediums or existing art-making parameters. It takes graduate students in the school three years to identify and deepen a very specific research area among the vast field of “experimental studies” in science, technology, performance, sociology, filmmaking, and other disciplines. In the first year, students participate in “public courses,” such as art history and liberal arts; in the second, they work closely with tutors and external supervisors on specific projects 1 ; and in the third, they research and produce projects of their own design. In addition to regular tutorials, the MA students are encouraged to develop organic ways of working together, sometimes in the form of reading clubs or group critiques. This education in “total art,” a term promoted by artist Qiu Zhijie, dean of the School of Experimental Art, attempts to forge new cultural meanings from various philosophies and systems of thought, regardless of time or location of origin, to produce work that responds to the cultural, social, environmental, and technological contexts of the twenty-first century. Under Qiu’s direction, the practices of experimentation and criticality are never abstract or wholly distinct: a student may write an argument and then develop the counter-proposition to it in their next project, a process in which they approach their subject from multiple and even conflicting perspectives. The students are also encouraged to study from divergent creative perspectives. When immersed in a project, students may be trained to see through the eyes of a writer, sociologist, performer, technologist, or other practitioner and are exposed to multiple methodologies of creation and experimentation during their course of study.

Aside from hospitals, MA-program research has also been conducted at theaters, in rural areas, and with teams at computer science labs and technology companies, sites where artistic methods can interweave and experiment with off-campus knowledges and experiences. These extramural endeavors allow the experiments conducted in the context of the School of Experimental Arts to interact with real-world needs and conditions, which in turn nurture students’ progress back on campus. For instance, numerous workshops on rural construction have taken place in Hanzhong, Shanxi, 1300 kilometers southwest of Beijing, during which the participating student-artists explored the scientific knowledge embedded in traditional handicraft. The workshops explored how this knowledge may offer an alternative perspective on the twenty-first-century human relationships with nature, folk tradition, and rural environments, broadening the scope of the program’s research into machine-based technologies.

Projects supported by Experimental Art students have demonstrated the porous boundaries between art and science and influenced ongoing scientific research. For example, “Large-Magnitude Transformable Liquid-Metal Composites,” an article published by a group of scientists from the Department of Biomedical Engineering in the School of Medicine at Tsinghua University, describes a highly transformable liquid-metal composite (LMC) that can easily change shape in large quantities. The article cites two artists, including Qiu Siyao, an MA student who spent three months working as the material lab’s artist-in-residence, together with Wang Hongzhang, a material scientist well-known for his work on liquid metal and soft materials. The findings of Qiu and Wang’s work helped create new ways of fabricating functional transformable composites that have significant applications in the development of future generations of soft robots. 2 The visual component of the scientists’ research paper derived from Qiu’s play and experimentation with this new, highly inaccessible material. In her video work Sisyphus, shown at Ars Electronica in Linz, Austria, in 2019, a small, uncanny piece of soft metal emerges from a river of liquid metals, climbs a mountain under the invisible control of a hidden machinery system, and, at the end of its journey, falls back into the river of its origin. This gravity-defying performance was produced not through visual effects but the actual physical attributes of LMC metal itself. “The researchers at the Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry at China Academy of Sciences, and the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Tsinghua University, gave me an in-depth overview of liquid metals, an atlas of data, images, and videos,” she said. “It felt like dominoes: I was given the first one and had to test endlessly each domino’s position and angle, to get a beautiful fall. Liquid metal to me is more than a mere ‘material,’ but a window to enter the world of scientific research, and I situate myself in it.”

Qiu Siyao, Sisyphus, 2019. Magnetic liquid metal, 3D-printed model, dimensions variable. © Qiu Siyao.

In 2019, Song Ruihua, a lead researcher at Microsoft Research, was invited to CAFA to lead a session on the application of artificial intelligence to visual composition and conversation generation. At the session, Wang Mengyao, an Experimental Art student, asked many questions and was later recommended by Song to the Microsoft Asia-Pacific Research and Development Group (ARD) to work with an artificial-intelligence team on the emotional experience of AI avatars. “As one of the ‘art interns’ at ARD, I collaborated with computer scientists in developing the criteria of visual data labeling and coproduced quite a few demos,” Mengyao said. At ARD, a team on “AI Creation” had been exploring how to train an algorithm to generate paintings of different genres, everything from Rembrandt to Mondrian, to study the underlying patterns that humans perceive as artistic style. Students from CAFA worked with the engineers on improving the performance of such algorithms via active discussion with the algorithm’s programmer about how style in its artistic sense can be translated into machine languages. Thus, the feedback from artists became embedded in the algorithms’ programming, making the process collaborative not merely in the front end, like using machine learning tools to create new works, but in the back end as well.

The works described so far might seem to have little in common with projects developed in traditional fine arts programs, but this supposed gap in the education landscape is precisely where the School of Experimental Art seeks to operate. The “two cultures” dichotomy between science and the arts still haunts intellectual and creative endeavor while the “third culture” has yet to emerge. 3 The school proposes that art, science, and technology do indeed share a cognitive common ground upon which there exist plural interpretations and definitions connected to specific geographical, industrial, and disciplinary contexts. To ponder the relationship of art and science is to engage with questions of their disjuncture. In a report titled “Future Art Eco-Systems,” the authors interrogate the notion of “AxAT” (Art x Advanced Technologies), which “can be understood as a form of technological innovation that is conditioned by a very different approach to technology—how it is developed, deployed, used and valued.” 4 The report introduces an “art stack model” as a space for research and development and concludes with the open question of what impact the art stack model might have on art education. The roaring tech industries in China provide an ideal testing ground for art that incorporates advanced technologies, yet the absence of historical precedent requires the School of Experimental Art and others like it to create a context for this art and to make topics of science and technology relevant and critical in educational curricula. Pondering the postgraduate education environment at the School of Experimental Art can be an complicated task, one that necessitates consideration of the numerous experiments, reformations, and collaborations that have been conducted under the aegis of an art school but with an eye on advanced technological innovation.

Interdisciplinariness—the defining quality of CAFA’s schools of Experimental Art and Design and many other programs in China—is the channel through which the “third culture” might come into being. Dean Qiu Zhijie, himself a provocateur of art, science, and technology, described the speculative or undefined nature of the experimental art field:

Compared to our international counterparts, China has less “historical burden” regarding the interdisciplinary framework. That is to say, the notion of interdisciplinariness here in China is less institutionalized and hence more liquid and emerging. However, we have to build almost everything from scratch with tremendous care given to the tension between incorporating international experience and real, local needs. I have profound belief in the underlying common ground of arts and science: we require MA and PhD students, including those working with “practice-based” programs, to be equipped with a mentality of experimentation, analysis, and criticality, as well as a strong will and openness to exchange with practitioners from other fields. We encourage students to draw a large mind map or visual framework to locate individual projects within a long-term research area, something like scaffolding. From the school’s perspective, we also facilitate the students with active cooperation among art theorists, artists, art institutions, and innovative enterprises. We are in a process of exploring what the “in-situ” for art, science, and technology in China looks like. We are still learning a lot.

And to this last point, CAFA has launched the EAST Program (Education, Art, Science, and Technology), which allows the school to interact with the innovation industry and research on the infrastructures of art and technology. Currently in its fifth year, the EAST Program has hosted annual conferences in which international educators and researchers on art, science, and technology, including Roy Ascott, Edward Shanken, Jeffery Shaw, Zachary Kaplan, and Eduardo Kac, to name only some, deliver lectures and curate interdisciplinary workshops. 5

Similarly, the School of Design at CAFA has initiated numerous programs at the intersection of various disciplines, following a “pedagogy reformation discussion” held in 2016 to rethink what “design education” means in a twenty-first-century context. The school’s earlier curriculum was very industry-oriented, but this new model looks speculatively toward the industries that might emerge in the future. Composed of “industry design,” “emerging technologies,” “design thinking,” “strategic design,” and “design theory” courses, the newly established program framework touches down at various, distributed locations in the product and industrial design fields. “The biggest mobility service provider nowadays isn’t any car company, but rather internet firms such as Didi and Uber,” said Fei Jun, a professor at the School of Design who was involved in the pedagogy reformation discussion. He referred to John Maeda’s Design in Tech Report 6 as influencing the discussion and described design’s potential to break through rigid disciplinary matrices and redefine the relationship between design, commerce, and society. “In the past, we understood design through a series of tangible objects: wood, stone, ‘physical outputs.’ With the rise of computational culture, we ought to also perceive design from the perspective of computing, systems, and frameworks.”

One result of this reformation discussion was the creation of an array of new research areas—including social-engagement design, eco-crisis design, art and technology design, creative engineering design, smart city design, and system design—that have resulted in radically diverse projects. 7 In this new scenario, research areas are proposed by professors based on their existing work, and each area is equipped with a supervisor group that can include mentors from other educational or cultural institutions. For instance, the “Wearable and Smart Technology” research area invites experts in design, jewelry, and fashion, as well as AI specialists from Hong Kong Polytechnic University, to supervise student work creating wearable devices with diverse applications in the real world, such as translating biometric data into poems or providing underwater camouflage. And in the “Synthetic Life and Ecology” research area, led by Chen Xiaowen, Feng Shuai, and Fu Yu, professors in the School of Design, students investigate the idea of “nature in the urban world,” a deliberately open-ended brief that encompasses topics from urban studies, ecology, and material sciences to pose highly speculative questions: What is the power relationship between plants? If a small area of wilderness in the city provided shelter for alien species, would these newcomers take more active roles than the current inhabitants of the city’s ecological system? How could a musical instrument be transformed into an environmental data censor and “perform” to real-time air pollution levels? In spring 2021, in the “Design Criticism and Curation” research area, which is intended to confront pandemic uncertainties and contemplate curating immateriality, students and supervisors produced a virtual exhibition and video game called “We¹Human²On³Mars4” in collaboration with NetDragon Websoft, a Chinese company that develops massively multiplayer online games. The game imagined a wave of virtual interstellar immigration, with Mars as the host of an alternative future of human civilization, a wild land for survival and mourning, exploration, and nostalgia. “Although planetary languages are becoming more sophisticated, human spirits are still weak and stagnant” says the game’s anonymous narrator.

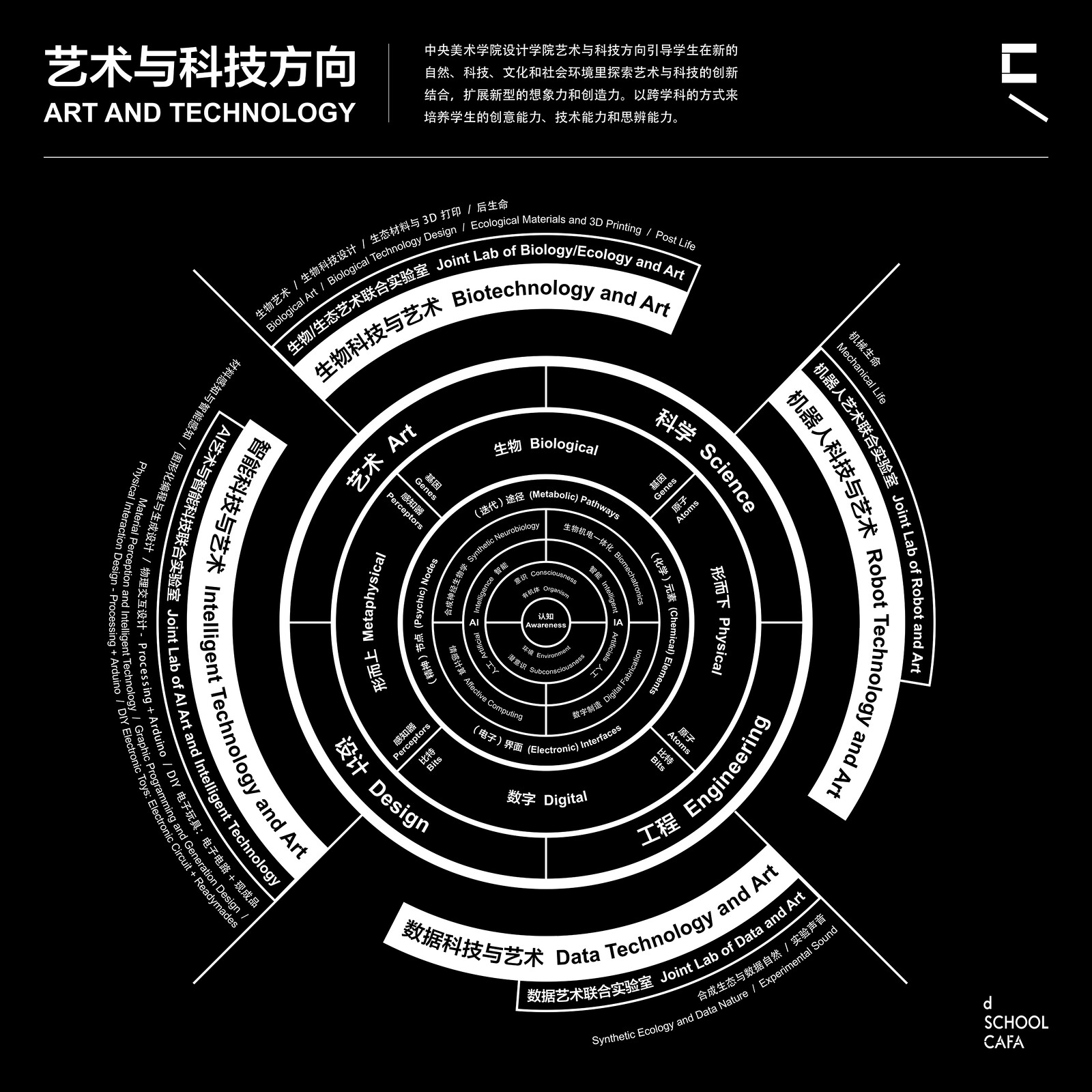

“Art and Technology” is another popular field of study at the School of Design. In a mind map diagram designed by professor Fei Jun, the field is envisioned as a dynamic system of multiple agents weaving together the key subjects of study—ecology, ethics, culture, life, technology, and society—into a structural form. Fei highlighted the idea of a “question pool” in his diagram: for each course, students are required to raise ten key questions about the course topic and independently develop at least five key concepts around each question. His research area engages discussions “about synthetic life and ecology, participatory culture, and social space narratives, the ethics of future technologies, the boundaries of the body, and so on,” Fei said. “What connects these dispersed topics are the core capabilities that we hope the students develop: analytical ability rooted in philosophy, technical ability derived from exposure to science and technology, and creative ability burgeoning from art”—capacities that are all critical to identifying questions at different functional, innovative, and ontological levels

In March 2020, the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China released a notice recommending that new research in the liberal arts and humanities incorporate technology literacy. For the architects of pedagogy, instituting interdisciplinariness, as the School of Experimental Art and School of Design do, requires attention and care to details and actively encourages complexity. The programs detailed here instill an eagerness to ponder the unnamed, the uncertain, and the emerging. At these schools and under their professors’ direction, “interdisciplinariness” is less a neat catchphrase than an evocation of, in Siegfried Zielinski’s words, “transformations of ‘creative data,’” which can be a perpetually in-motion, unending process. The tension on He Xuan’s eyelashes, the Sisyphean errands of Qiu Siyao’s liquid metal, the exploration of urban ecologies, and the founding of another world on Mars, among other graduate projects, operate within a web of discourses, knowledges, methods, and experiments. This work develops not in the comfort zone of concrete trajectories but in a state of flux for those curious and eager to participate in the uninhibited growth of new creative fields. Students and professors at the School of Experimental Art and School of Design at the Central Academy of Fine Arts seek not to explore uncharted territory but to create it.

Recent tutors and external supervisors include artists Cao Fei, Jeffery Shaw, and Xu Zhen, among others; specialists from other fields include He Xiaodong, of the JD AI Research Department, and He Beili, of the Department of Anthropology at Peking University.

In existing robot technology, rigid internal components and mechanisms prevent fluid, cohesive movement. The transformable liquid-metal composites experimented with in this research allow robots to change shape easily and return to their original resting forms and better approximate human locomotion. Hongzhang Wang, Yao Youyou, et al., “Large-Magnitude Transformable Liquid-Metal Composites,” ACS Omega 2019, 2311–19 →.

C. P. Snow, The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959).

Serpentine R&D Platform, Future Art Ecosystems, Serpentine Galleries, 2020 →.

EAST has hosted a “Planetary Collegium” PhD teaching workshop led by Roy Ascott, a gene-editing workshop in collaboration with Peking University, and a machine-learning workshop, among others. The New York–based art and technology platform Rhizome launched its “7 × 7” program as part of the EAST 2018 season. “7 × 7” pairs seven artists with seven visionary technologists and challenges them to make something new—an artwork, a prototype, or whatever they imagine. See →.

See →.

See →.