RAT school of ART organized “The Forest Is In The City Is In The Forest – II” with The Forest Curriculum to encourage thinking on current environmental crises from an Asian perspective through the lenses of violence, politics, and ecological history. Originally intended as an in-person summer school but moved online due to Covid-19 restrictions, the program was presented from October 2020 to January 2021 and sought to build artist networks by hosting lectures, performances, and workshops. The intentions of “The Forest Is In The City – II” might seem contradictory: both “connecting the few and the multitude,” as permitted by its digital migration, and “constructing in-depth networks,” which would have resulted from in-person exchanges. But these intentions speak to the principles that have guided RAT for the last seven years.

Started as an art space in 2014, the Seoul-based RAT school of ART operates as a learning platform but, at the same time, builds community not only among artists but between artists and the public. According to Dirk Fleischmann, the founder, and Mijoo Park, the director, RAT is a community where art and ideas can be discussed, not merely a small group of practitioners with specific pedagogical dogmas or an academic laboratory that develops a learning process but does not demand a change in the way art is taught. The goal is to support people from various cultural, educational, and socioeconomic backgrounds who interact with and learn from each other through artmaking. To this end, RAT has worked to connect the few with the multitude through the “RAT Talks” lecture series and to build in-depth networks through the “RAT Membership Program.”

To examine RAT’s origins, it is necessary first to survey the landscape of the Korean art scene in the years before the program was founded. Various biennials and many public and private art museums were instituted in Korea in the 1990s, and by the 2000s, many alternative spaces like Alternative Space Loop, Alternative Space Pool, Insa Art Space, Project Space Sarubia Dabang, and Ssamzie Art Space opened their doors. Korean galleries gained prominence in the global art market, and international curators and artists began to visit Korea with greater frequency. Dirk Fleischmann was one such artist, arriving to Korea from Germany. In 2009, he began hosting the “Black Sheep Lecture Series” at Hansung University in Seoul in collaboration with Hunyee Jung, a professor of painting at the university. “Black Sheep Lecture Series” invited international artists like Luchezar Boyadviev, Sabine Kacunko, Antoni Muntadas, and Sean Snyder to give presentations on art practice with the intention of creating a new platform for the discussion of contemporary art. Centered around exchanging information with artists and curators who have different careers and experiences, these sessions were designed to be simple and casual, eliminating the hierarchy of the lecture format. Speakers and guests all sat on the floor together and, after the main presentation, developed dialogues through Q&A sessions and in-depth conversations.

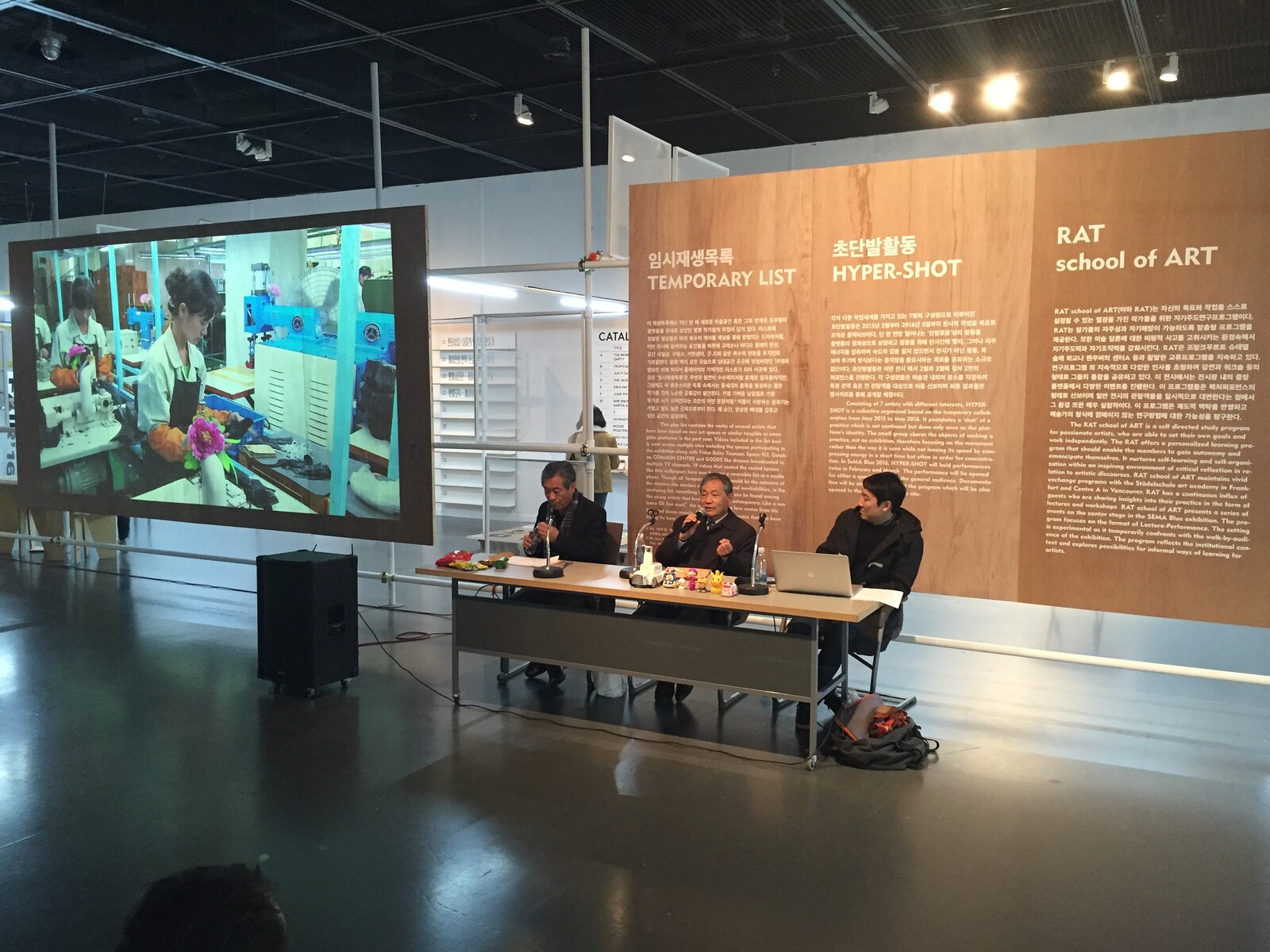

Five years after the first “Black Sheep” session, Fleischmann established a space in the Jongno-gu neighborhood of Seoul with Mijoo Park, an independent curator, to give his now-nomadic lecture series a permanent home. From there, it developed into an independent learning program, and in September 2014, “Black Sheep Lecture Series” became “RAT Talks.” Like its predecessor, “RAT Talks” were free and open to the public and consisted of a presentation and extended Q&A session that sought to “connect the few and the multitude” through the discussion of contemporary art. About 110 international and Korean art professionals like Heidi Ballet, Seulgi Lee, Kyong Park, Philippe Pirotte, Ahmet Öğüt, Warren Neidich, and You Mi have participated in the last seven years, and the talks, RAT’s flagship initiative, have provided an alternative to the programming more commonly found in the Korean art world, which lacks the kind of informality that RAT’s contemporary art education exhibits. Recently, contemporary art education in Korea has become more developed, and major art museums like the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and the Seoul Museum of Art have tried to engage with and expand access to contemporary art, but public understanding of it and its ideas is still not widespread. In Korea’s public education system, art has historically been considered an insignificant subject, and the art curriculum deals with Korean and international art history from antiquity to the 1960s and ’70s. In offering a space to listen to insights on artistic practices and have conversations, “RAT Talks” has filled the gap between public education and discourses of contemporary art happening internationally and online.

Paralleling “RAT Talks,” RAT developed a then-unprecedented series of courses for small groups of regular participants. The “RAT Membership Program” began by questioning how art education is practiced in established institutions, namely Korean art colleges. Entrenched in Korea’s slow-to-respond and conservative university system, Korean art colleges have long focused on teaching technique as a means of laying the foundations of Korean contemporary art, aiming to cultivate “good” artists. In-depth education in art theory is limited and generally only taught in art history or theory departments. Even if theory courses are available in an art practice department, they likely focus on European and American art history in the twentieth century. The tendency to privilege technical skills over theory is also obvious in the college entrance examination system, in which art colleges select applicants based on practical tests such as drawing and watercolor for their painting programs, “modeling and subject heads” for sculpture, and “idea and expression” for design. This formulaic way of assessing artistic talent has given way to a genre of “entrance examination art” and a private art education system designed to teach skills for the entrance exam. Along with the recent changes to the entrance examinations to all Korean universities, new standards such as student interviews and grades-based admission have been introduced to the application process, but many art colleges still maintain the old practical tests as a barrier to entry.

As well, most Korean art colleges divide their majors by medium. This is true even of Seoul National and Hongik universities, schools with long histories that have produced well-known Korean artists like Choi Jeong Hwa, Lee Bul, Park Chan-kyong, Do Ho Suh, and Haegue Yang. The art college system, which has been stuck on the question of creating better rather than thinking creatively, has not been able to keep up with the interdisciplinary flow of contemporary art, even after the 1993 opening of the Korea National University of Arts (K-arts). There, the School of Visual Arts divides courses into Fine Arts, Design, Architecture, and Art Theory departments, but unlike other university art colleges, entry to the Fine Arts department is based on its own test that examines ideas and creativity rather than technical skills alone. The structure of its curriculum is also different: for the first two years, students develop a general perspective on various fields of visual arts, and in the final two years of the major course, they work and study in a studio system under a specific professor such as Juyong Lee, Minouk Lim, and Hwayeon Nam. Perhaps because of this unique structure, K-arts has been unrivaled for over a decade in cultivating promising contemporary artists working in Korea. Other universities like Kaywon University of Art & Design and Seoul National University of Science and Technology have also attempted to overthrow the classic curricula of the Korean art colleges, but the emphasis on technique over concept and medium-specificity over interdisciplinary practice still predominates. The failure of this system to create contact with the current international art scene has also resulted in a lack of community among artists who finished their studies in Korea and those who studied abroad.

RAT was alert to this and has sought to facilitate community organically through its own regular programs by “constructing in-depth networks.” Fleischmann and Park work with the awareness that the art world is not a flat landscape but comprised of hierarchies, especially in Korea. RAT seeks not to level these hierarchies but to create a space where a relationship like student–teacher is completely readjusted. In a nod to horizontality, RAT does not to follow the academic system and refers to participants in its programs as “members” rather than “students,” emphasizing the importance of participation in community-building. Members are recruited twice a year in the spring and fall, and anyone who wishes to can became a member with only a small registration fee and a review of their portfolio—a radical departure from the art colleges’ highly structured application process.

The curriculum of the “RAT Membership Program” is composed of three sections: “Reading,” “Studying,” and “Critiques.” Since it began in spring 2015, an average of ten members have enrolled each term, and members can re-register for the program because each term is unique. At the beginning, the content of each discussion and reading program was prepared by Fleischmann and Park and included an artists’ workshop with Jewyo Rhii and a theory seminar with Hyunjin Kim. But after establishing a stable structure, content for the learning programs has been organized democratically so that members decide which artists and curators to invite for discussions. In the “Reading” section, members have engaged with the concerns of contemporary art through Korean and international publications, including various Korean biennial catalogues and books like ’90s Korean Art and Postmodernism by Hyejin Moon, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition by Rosalind Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide by Krauss and Yve-Alain Bois, Exiles of the Screen by Hito Steyerl, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space by Brian O’Doherty, and The Radicant by Nicolas Bourriaud, among other texts. In the “Critiques” section, members discuss their practice in one-on-ones with Fleischmann and Park or in group critiques with fellow members in which their work is assessed and discussed in depth. The “Study” section, structured to connect practice and theory, is RAT’s most flexible format. In the beginning, it hosted workshops, seminars, and screenings, including films by John Cassavetes, Sook Hyun Kim, Guy Debord, Todd Haynes, Yoon-Suk Jung, and Kelvin Kyung Kun Park.

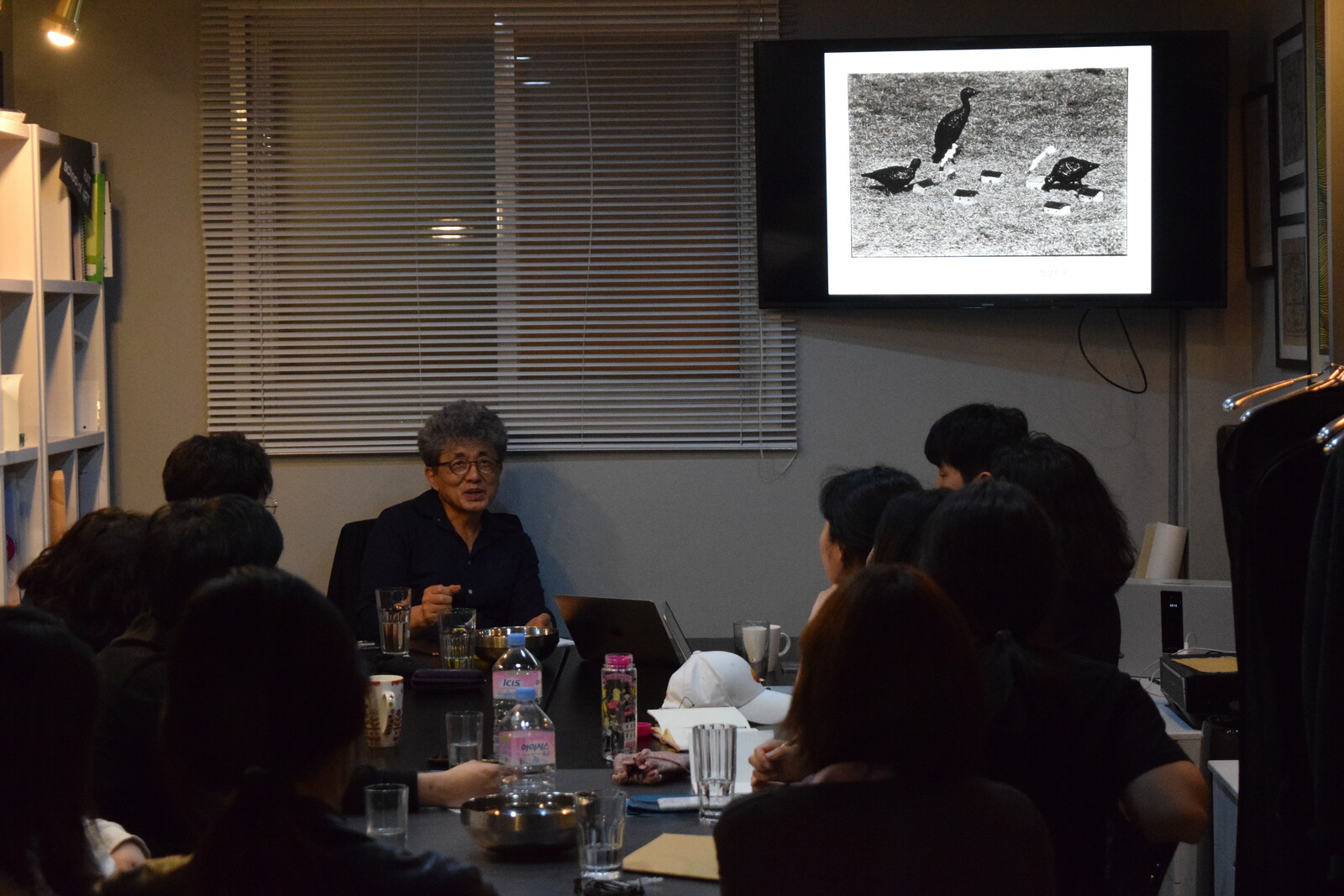

Since fall 2016, the “Study” section has evolved into a program called “One Day Faculty” to accommodate requests to host established artists, curators, and critics of other generations at RAT for a day. Through discussions with the members, many of whom are practicing artists themselves, several lecturers have been invited to lead a unique workshop or seminar. So far, the series has hosted Hyunjin Kim’s session on Asian modernity and contemporary art, workshops by internationally active Korean artist Jewyo Rhii, a course on art history after 1960 taught by Soyeon Ahn, and a writing workshop by Paul Jy Nah, among others. “One Day Faculty” is conducted in different ways depending on the will and disposition of each lecturer, and so some have led seminars while others have organized group critiques. In the cases of artists Ahn Kyuchul, Minouk Lim, and Haegue Yang, questionnaires about artistic practice, research, and building a career were collected before they came to RAT and were intensely discussed on the days of their visits. By adapting to the method that most effectively reflects the interest of each lecturer, “One Day Faculty” generates deep dialogue about the professional field, and members have the opportunity to understand the contemporary art scene in depth through honest questions and answers.

RAT has worked to provide a self-paced learning program for passionate artists by allowing them to set their own goals and work independently. RAT offers an environment that encourages critical thinking about art discourse while creating personalized learning programs for artists so that they can liberate themselves from the mostly conservative confines of higher education in Korea. Since it was founded and throughout the process of maintaining its programs, RAT has provided members with opportunities to present the work they developed through the RAT programs, and in 2015 it launched “RAT Lab.” In this initiative, members present their works in the RAT space in the form of small-scale exhibitions. In doing so, they test how the works exist outside the studio, in the exhibition space, gaining some insight into curatorial practice in the process. Since the first members’ show, the group exhibition “Sam Chang,” various small-scale solo shows have been held at RAT and in collaboration with the One and J.+1 gallery, which presented larger-scale solo exhibitions in 2017 and 2018, including ones by RAT members Bigo, Sun-young Huh, and Heewoong Jin.

In establishing a unique learning structure independent of the Korean education system, RAT has enabled artists in Korea to voluntarily develop their practices while forming connections with the global art world. Notably, the courses at RAT are taught primarily in English, an effect of the predominance of Europe and the United States in contemporary art discourses. Fluency in English is not widespread in Korea because there are few opportunities to use it in everyday life, and RAT does not provide language instruction. But it has encouraged members to take the risk of using their own metaphors and terms by increasing their frequency of speaking and listening to English, regardless of their individual skills. Working in English has also allowed RAT to link its activities with international contemporary art scenes and bring the Korean art world into contact with the international art world through various partnerships. For instance, in 2015, Tobias Rehberger’s class at Städelschule, the academy of fine arts in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, visited Korea to participate in the RAT programs. In 2017, Peter Fischli’s Städelschule class followed, and two RAT members participated in the Städelschule exchange-student program. In addition, through its annual exchange and residency program with Centre A in Vancouver, Canada, RAT has hosted artists and curators in Seoul who have participated in RAT’s programs as members or lecturers. As part of this exchange, Centre A has hosted exhibitions organized by RAT, including “Unstable Oscillation” in 2019, “Wishy-Washy Bodies” in 2017, and “/Unpackaged Garden/” in 2016.

RAT has been also actively involved with various institutions in the Korean art scene. In the mid-2010s, when RAT was founded, more independent art institutions were opened in Korea than ever before. The alternative spaces that had been established decades earlier were unable to accommodate the new interdisciplinary and post-internet activities of the younger generation, so young artists in their twenties and thirties created their own spaces to host exhibitions and programming. In 2016, fifteen of these initiatives and new spaces—often grouped as “Sinsaeng Gonggan”—were invited by the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA) to participate in the exhibition “Seoul Babel.” RAT’s contribution to the exhibition included transforming the SeMA space into a platform for lecture performances like Vad Hahn’s Electronic Lecture Opera, Soo’s Chunjang Road, Che Onejoon’s discussion about the Kaesong Industrial Zone, and Byungseo Yoo’s noise performance. The same year, RAT also collaborated on the “Infra-School” project of the 11th Gwangju Biennale, led by artistic director Maria Lind. Rather than establishing a new, independent education sector at the Biennale, Lind sought to expand and strengthen connectivity between the exhibition and local art organizations by contacting nine existing educational institutions based in Gwangju and Seoul. For “Infra-School,” RAT offered lectures or workshops with Bik Van der Pol, Céline Condorelli, Fernando García-Dory, siren eun young jung, Bernd Krauss, Julia Sarisetiati, and Tommy Støckel in conjunction with “RAT Talks.” In addition, Biennale curatorial team members Azar Mahmoudian and Margarida Mendes held a group critique with RAT members.

Because of the gentrification of the Jongno-gu neighborhood, RAT moved in winter 2017 to the Yongsan-gu area of Seoul, into a space more suitable for seminars. Coinciding with this move, the program changed focus so that members became more involved in its direction, and discussions grew more in-depth through four- or five-week sessions led by one visiting artist or curator rather than a fifteen-week series of seminars with different guests. “One Day Faculty” programs reflecting the needs of the members were also strengthened, and it became possible to have more intimate networking through casual dining events because the new space had a kitchen. The “Critiques” section was also strengthened to invite more outside experts to provide critiques from a wider range of perspectives. Sometimes they were invited more than once to enable long-term and continuous development of the members’ practices.

As the characteristics of the space and the atmosphere changed, in spring 2020 RAT changed the overall direction of the programs to expand contemporary discourses on Asian art history and Western politics and economics and also deepen members’ self-directed learning. RAT reorganized the programs into seminar units, and although the details of each seminar were left to the lecturers, RAT reinforced its role as a platform for possible discourses in Korea and dealt with international art issues from a Korean perspective, a position that has garnered RAT critical recognition in the international art scene. Three curators were invited to launch the pilot program of seminar units in earnest: Hyunjin Kim discussed the problems of Asian modernities and the Western colonial model of society, and the members were encouraged in turn to critically rethink efforts by East Asian societies to adapt Western infrastructures in “Modernity Discourse and Practices of Visual Arts Controversing the Modernization of Asia.” Je Yun Moon ran “Performance Study – Performative Turn” to discuss the topography of contemporary art that was expanding beyond the traditional boundaries of temporal art and spatial art. In my own seminar, “Throwing Me Toward Dystopia – Symptoms of Change in Contemporary Art in the Anthropocene Era,” RAT members were introduced to the sociopolitical issues and discourses of the Anthropocene. Each of the seminars became a unit and were held two to four times from September to December 2020. “Critiques” also became a unit, which Park led as “Taking Care of Your Works” over seven sessions.

“The Forest Is In The City Is In The Forest – II” reflects RAT’s changing direction. Bringing to the surface issues ranging from Cold War history to shamanism, land sovereignty, food security, language, and infrastructure, the seminar enabled art practitioners to have free discussions about conditions that are faced by people all over the world. This program invited Ayesha Gergis, Ho Tzu Nyen, Jane Jin Kaisen, Mali Weil, Struggles for Sovereignty, Cristian Tablazon, Sung Tieu, and Natasha Tontey to lead the discussions. The public’s reaction was extremely enthusiastic: because it was hosted online, over one hundred people at a time participated in the seminar and expressed their opinions freely. Expanding creative thinking on environmental crises, in January 2021 Park completed her tenure as RAT director with the program “Endless Summer – Island Within the Land,” held on Jeju, an island off Korea’s southern coast. It was designed as a camp or a temporary platform to specifically explore, through the natural and social formulation of “islands,” how ecosystems react to the climate crisis and how this effects society. Operated as a one-week residency program after several revisions due to Covid-19 restrictions, “Endless Summer” supported participants in art-making and discussions about the physical reality of the climate crisis as witnessed on Jeju.

RAT has continuously transformed itself as an art community in its collaborations with art professionals and the public and as a self-learning program that actively responds to the needs of its members. It is now poised to provide an alternative to the art education system in Korea and establish itself as an art space and a community, having created both discourses and networks through “RAT Talks,” “RAT Membership Programs,” and various partnerships. At a time when the gap between artistic practice and art education has gradually narrowed, RAT’s lightweight format has allowed it to respond quickly to emerging discourses, a necessity in the reorganized post–Covid 19 art world.