“We cannot say what new structures will replace the ones we live with yet, because once we have torn shit down, we will inevitably see more and see differently and feel a new sense of wanting and being and becoming. What we want after ‘the break’ will be different from what we think we want before the break and both are necessarily different from the desire that issues from being in the break.”

—Jack Halberstam, introduction to Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study

A wave of writing on radical education appeared in the wake of the 2008 financial collapse and surfaced again three years later during the Occupy protests. Both moments rehearsed our current one: increased economic inequality, dramatic disinvestment in public goods, and an accelerated dependence on debt to access education. These inequalities, while addressed polemically, were rarely addressed materially. Voyeuristic appraisals of programs like AltMFA, the Black School, Mountain School of Arts, and Bruce High Quality Foundation University often positioned these radical alternatives more like novelties than serious replacements of the established art education institutions and, in turn, regulated a cruel optimism of those institutions and their promises. 1 Much of this writing was sensory, first-person, and romantic: the reader might be informed of what a seminar room smelled like but not what the students did there nor how they came to education, let alone any discussion of the institution’s pedagogical ideology. The establishment crowded out the alternative and cast these radical schools in narrow terms of opposition rather than as possibilities to serve the artists that traditional institutions often excluded. The MFA, then and now, perpetuates professionalization, offering access and art world visibility for considerable debt-backed fees instead of an education that empowers artists to challenge the system’s fundamental inequities. This exchange was commonly accepted and influenced what was written about and how, what was seen and what was buried.

Critical attention confers legitimacy, and while a lack of a sincere engagement with the alternative is not the only problem faced by radical programs, it contributes to keeping new, divergent forms of education suspended between launch and long-term viability. For radical and utopic models to develop, they are in need of a new kind of evaluative writing, one that enables prospective students to understand the definitions of an education that encourages a deep, investigative, and expansive art practice. This writing must be material rather than idealized; embodied rather than voyeuristic; and focused on subjects (the students and their work and the teachers’ articulated pedagogies) rather than subjectivities. It ought to answer not only how but what and why. Most importantly, it must be patient, rigorous, and observant. As Fred Moten and Stefano Harney outline in The Undercommons, their collaborative exploration of a divergent space for study and the development of a new, free commons within society, “We owe it to each other to falsify the institution … We owe each other the indeterminate. We owe each other everything.” 2 Significant criticism of the MFA system certainly exists, but for all of the signaling, why has no divergent program established itself as a serious replacement of high-debt higher education?

Enter Dark Study. Developed by Caitlin Cherry and Nicole Won Hee Maloof, Dark Study is a new para-institution launched in January that operates beyond the traditional structures of education to counter the inaccessibility and weaknesses of art school that make it an unrealistic, and inhospitable, place for so many artists to make their work. Conversations about Dark Study began last winter, before Covid, between Cherry, Maloof, and Nora Khan amid their disappointment with the limitations imposed by discipline-centric pedagogy, unresponsive curricula, and the accelerating precarity of adjuncts. When the first Covid lockdown was initiated and education went from in-person to online, the founders’ idea of a decentered, radically interdisciplinary alternative to the MFA found form. Exceeding medium specificity and technical training, Dark Study offers an education in cultural and media theory and empire and capital’s roles in the development of contemporary art. The program addresses the problems and traumas Cherry and Maloof encountered in their own educational experiences—both as students and as professors—and challenges preexisting forms of education in traditional institutions that prize results-oriented evaluation on a limited timeline in a discrete space. Because it is free, Dark Study dismisses the contract between art world success and debt. It offers an immersive space of study, one that is responsive to students’ needs, and seeks to fulfill education’s capacity for community-building through shared growth rather than individualized participation in a system designed to satisfy the demands of capital.

Running a free program that stands a chance of shifting power away from traditional institutions comes with countless obstacles and requires a combination of intellect, critical strategizing, and organizational skill. As both practicing artists and educators, Cherry and Maloof offer unique perspectives from which to deliver a potential undercommons in art education: Cherry’s is a hybridized practice that involves virtual reality, installation, and painting to question the role of the market and its presence in the reification of art as a commodity. She can as readily and easily discuss Alexander Galloway’s Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralization as contemporary figuration. Maloof uses printmaking, bookmaking, and video to explore folkloric and personal narratives and representations of labor. Over the past year she has led an underground and international Marxist theory book club. Cherry teaches painting at Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts and Maloof at Sarah Lawrence College. Together, they have assembled a roster of visiting artists and advisors—Sondra Perry, Jesse Darling, David Xu Borgonjon, Che Gossett, and Serubiri Moses—who bring with them experiences and pedagogies grounded in the overlaps of the fields of art, technology, and culture.

Dark Study received 180 applications from its first call, a testament to artists’ readiness for an alternative. In the Instagram announcement, Cherry and Maloof kept Dark Study’s pedagogy and intentions deliberately vague to resist “the call to order,” a strategy adapted from Moten and Harney’s Undercommons. Due to this intentional abstraction of their process, the applicant pool was impressively heterogeneous, interdisciplinary, and diverse across ethnicity, age, class, education, and professional experience. The application-making process was carefully considered. The school’s portal states:

Community-building in schools is often talked about as if the process begins on the first day of school—a group of students happens to find themselves in the same space, at the same time. However, the community formed in the classroom is engineered long before the group gathers; its shape, the conversations it will likely have, is rooted in the application form. An application form is a subtle form of gatekeeping. If a school truly wants to give opportunities to those who have been locked or forced out of higher education, then the usual signs of access and training embedded in the application must be reassessed. Using the same old “natural” markers of “success” can only reproduce the hostile conditions that exist in society at large, undermining any attempts at creating an inclusive community before the first day arrives. 3

When Maloof and Cherry evaluated the applicants, the ideology of the school was put to the test. “We had a stated aim for the school. We had to make sure that the way we were assessing people actually matched that goal,” Maloof says. “It’s really easy for those things to not match up, which is a criticism we have of institutions, and how they are able to keep people out while they proclaim this ‘welcoming of diversity.’” Some applicants were artists with MFAs or doctorates from elite institutions, and others were musicians, gallerists, physicists, robotics engineers, or artists who had established exhibition records, perhaps thinking that Dark Study was more akin to a cultural think tank or postgraduate program like the Studio Museum Residency or the Whitney Independent Study Program than an MFA. Maloof explains how they handled these expectations within the application process: “Some people with multiple postgraduate degrees applied, some with master’s and some enrolled in PhD programs. We did tend to weed out people who had an exceptional amount of education, because it was clear they could, through their own means, access such programs on their own and afford them. It didn’t seem like we would do them a service, and they would be taking up a space from someone who doesn’t have access to those higher institutions of education, and that’s who we were really targeting. We weren’t biased against individuals with lots of access, but that signaled to us they had tools in place to find access on their own.” Artspeak also proved a dead end with them. “If we sensed too much of that intellectual posturing in their applications, which often is rewarded in art schools, it was a red flag.”

Cherry and Maloof insisted on the application being free and avoiding the exorbitant fees of Submittable and SlideRoom, which proved to be a challenging administrative problem. “Our application was essay heavy. We had to tell ourselves, ‘We have to slow down, spend more time with each application,’” Cherry says. “To thoughtfully consider each candidate would take time.” Dark Study did not require transcripts or letters of recommendation, traditional signals in the application process that vet applicants with better connections. One especially helpful prompt for applicants was to provide an “Alternative Story,” a biography of failures, a negative CV made up of rejected applications and barriers that withheld access. To demonstrate the transparency and inclusivity that traditional institutions often only speak to, the founders provided their own versions as examples on Dark Study’s website. In her bio, Cherry writes

I didn’t come from a creative family. My mother was a secretary and my father worked most o his life as a worker on an automotive assembly line. Growing up in Chicago, I lacked any particular motivation to do anything but sports and art. My GPA and ACT scores would have hardly gotten me into a decent state school, I certainly wasn’t Northwestern bound. It took me a while to become “good at school.” My parents supported my ambitions the best they could. I spent a year at a community college before I was able to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. 4

Having narrowed the applicant pool, Cherry and Maloof interviewed twenty-five finalists to get a sense of the kind of cohort they could assemble and decided to accept all of them based on their level of work, an assessment of their need, and the founders’ critical self-evaluation of what needs they could reasonably meet and address through teaching. Attending class from Oklahoma, Kentucky, California, New York, Ghana, Mexico, and China, among other places, the first twenty-five students are diverse in ethnicity and gender identity. “The reality is it takes risk, vulnerability, and time,” Cherry says. “If you put these candidates in front of a different panel, you’d get a different program.”

Lela Welch, Investment, 2019. Durational performance, Vaseline, washed silica sand, casting plaster, wood, water, plastic buckets, mixer, Masonite, projected image, and self.

One of those candidates was Lela Welch. She dropped out of college in 2008 as her struggles with addiction became unmanageable, and although she was able to finish her bachelor’s degree in 2018, the path back to school proved difficult. Between 2008 and 2018, Welch worked at homeless shelters, a start-up, and in addiction treatment, and is now a temp administrator at a psychiatric office in San Luis Obispo, California. Though Welch has the lived experiences that MFA programs often suggest they want in a candidate, her location, schedule, and educational history preclude her from a traditional MFA. Welch felt like it was time for her to reenter a structured community learning environment and was looking for critical engagement and feedback from peers, a “correcting experience,” she says. She is in Dark Study class from six to eight o’clock in the morning, before going to work at the psychiatric office. At noon, she has an hour break and catches up with reading and class discussion over Whereby. After work, meetings, and class, Welch is usually home by eight o’clock in the evening and able to put in some extra time studying. Typically, she expects to read about twenty pages of assigned reading per class, in addition to answering course questions and preparing for discussions. Recently, Welch has been reading sections of theory that seek to explore third spaces of operation within institutions, like Halberstam’s The Queer Art of Failure and Rasheedah Phillips’s essay “Communal, Quantum and Afrofutures: Time and Memory in North Philly” from Black Quantum Futurism: Space-Time Collapse II. 5 Her practice involves actions and objects, and she is interested in the realities created by artificial hells. In her piece Investment (2019), the artist’s partner poured casting plaster over her while she sat in a constructed box filled with and, reenacting with her body the early steps in the bronze casting process. At the end of the three-hour performance, Welch stood up from the hardened plaster, leaving a relief where her body had merged with the fabricated landscape. Welch is planning two ambitious projects, in both scale and funding, and is seeking guidance on how to realize them materially and critically. The discussions in Dark Study have enabled her to question her work: whether she should use her own body in performance or invite group participation, the valances of class that the interactions of her performances involve, the audience it has addressed in the past, and who it will address in the future.

Lela Welch, Investment, 2019. Durational performance, Vaseline, washed silica sand, casting plaster, wood, water, plastic buckets, mixer, Masonite, projected image, and self.

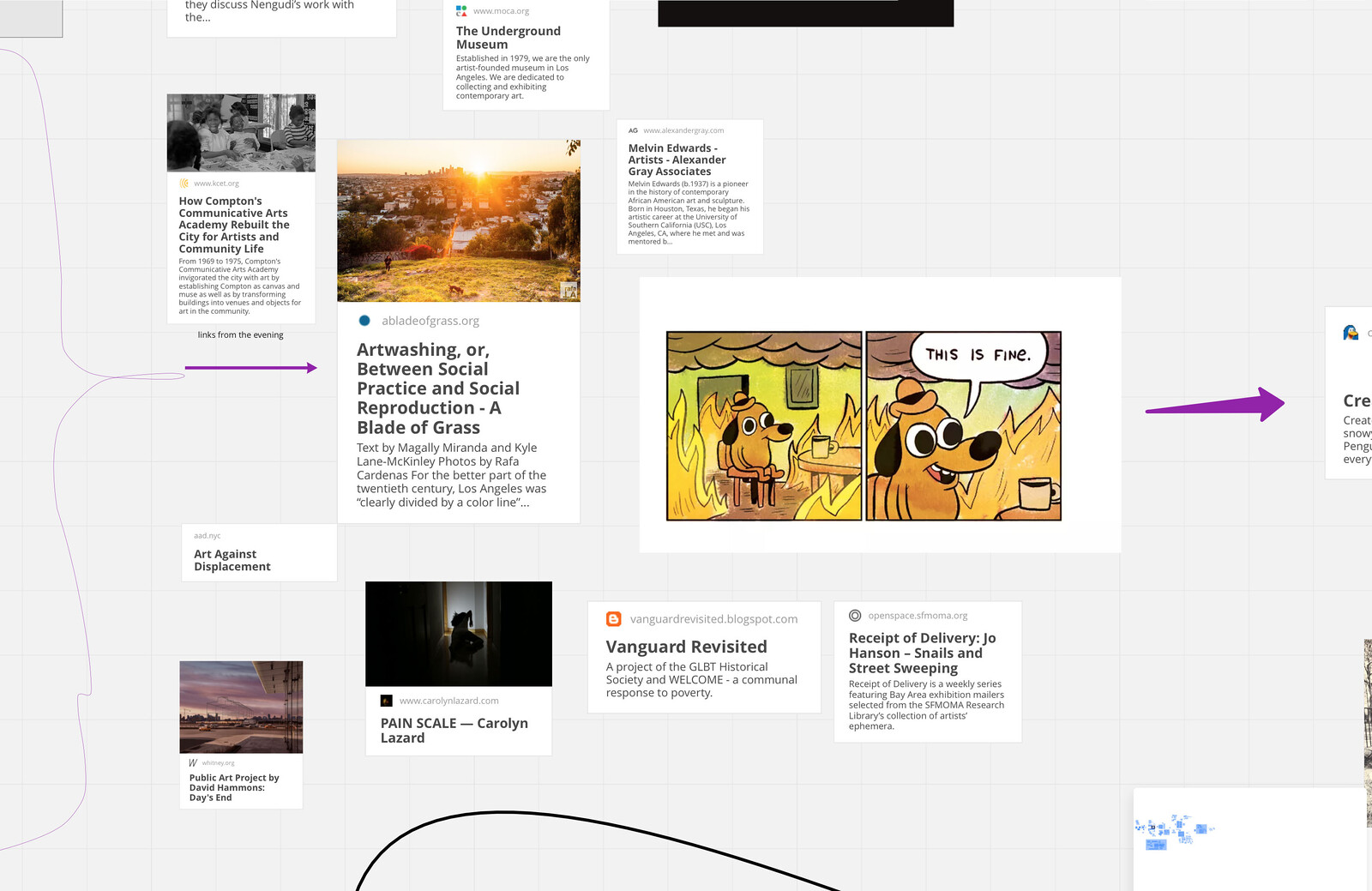

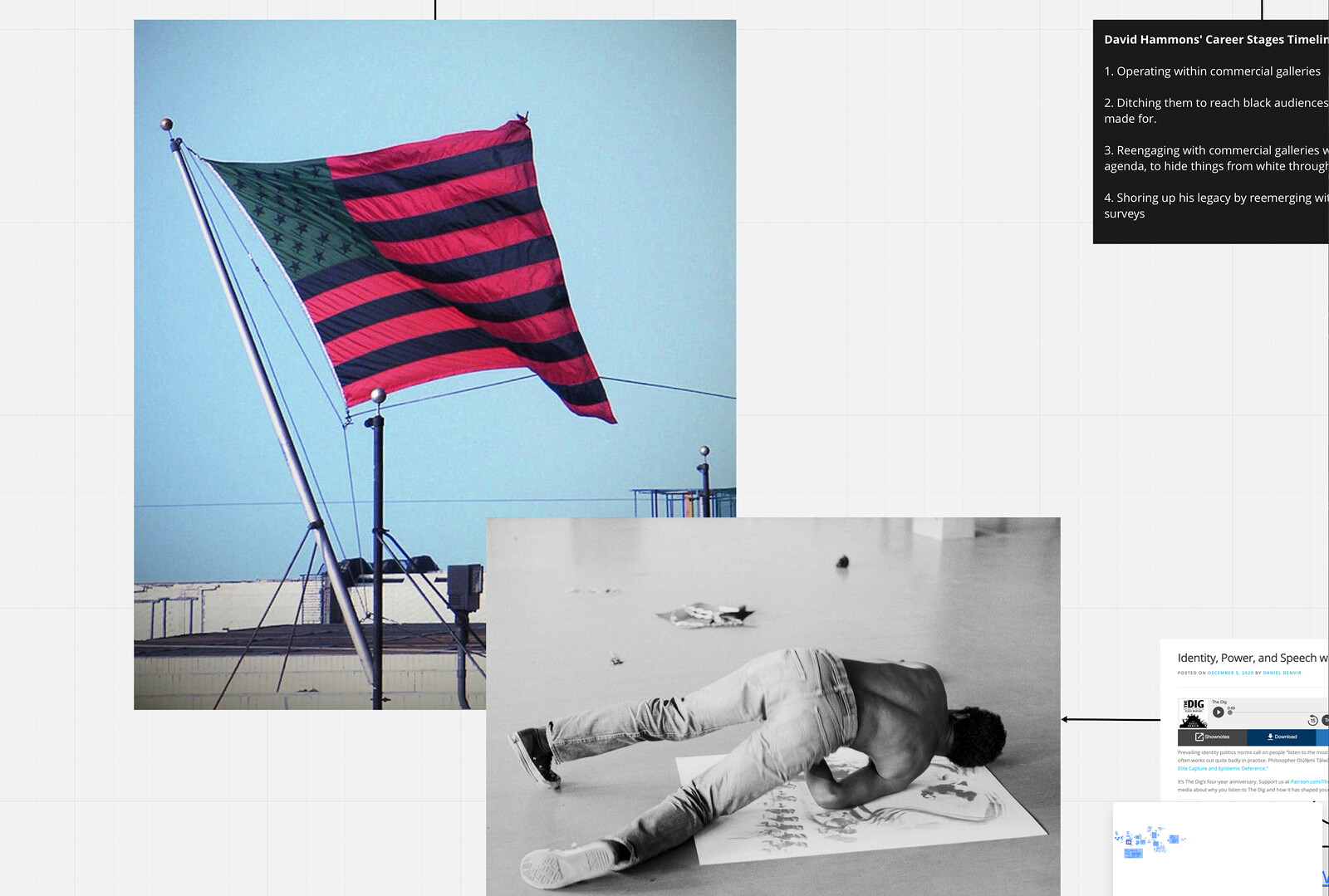

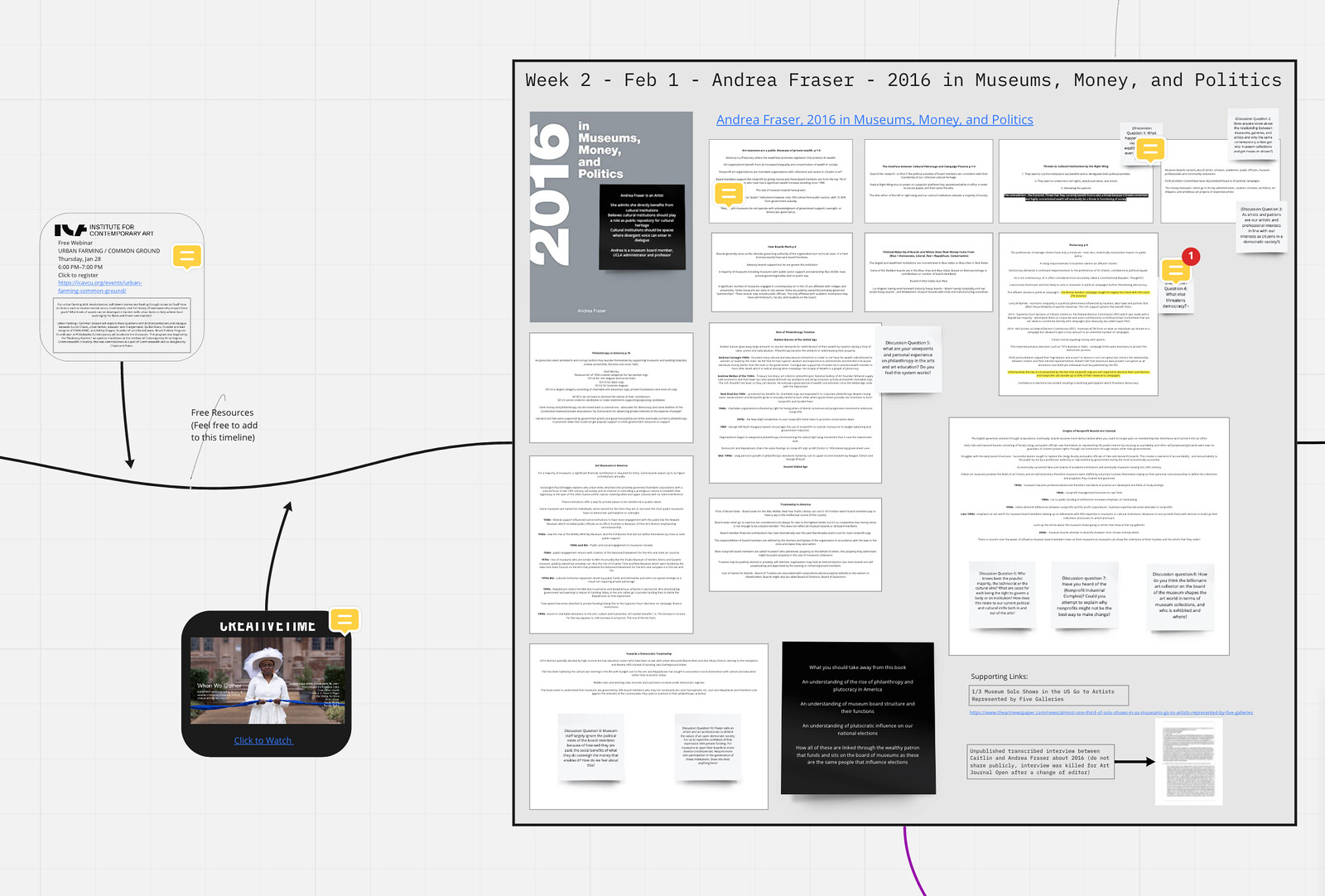

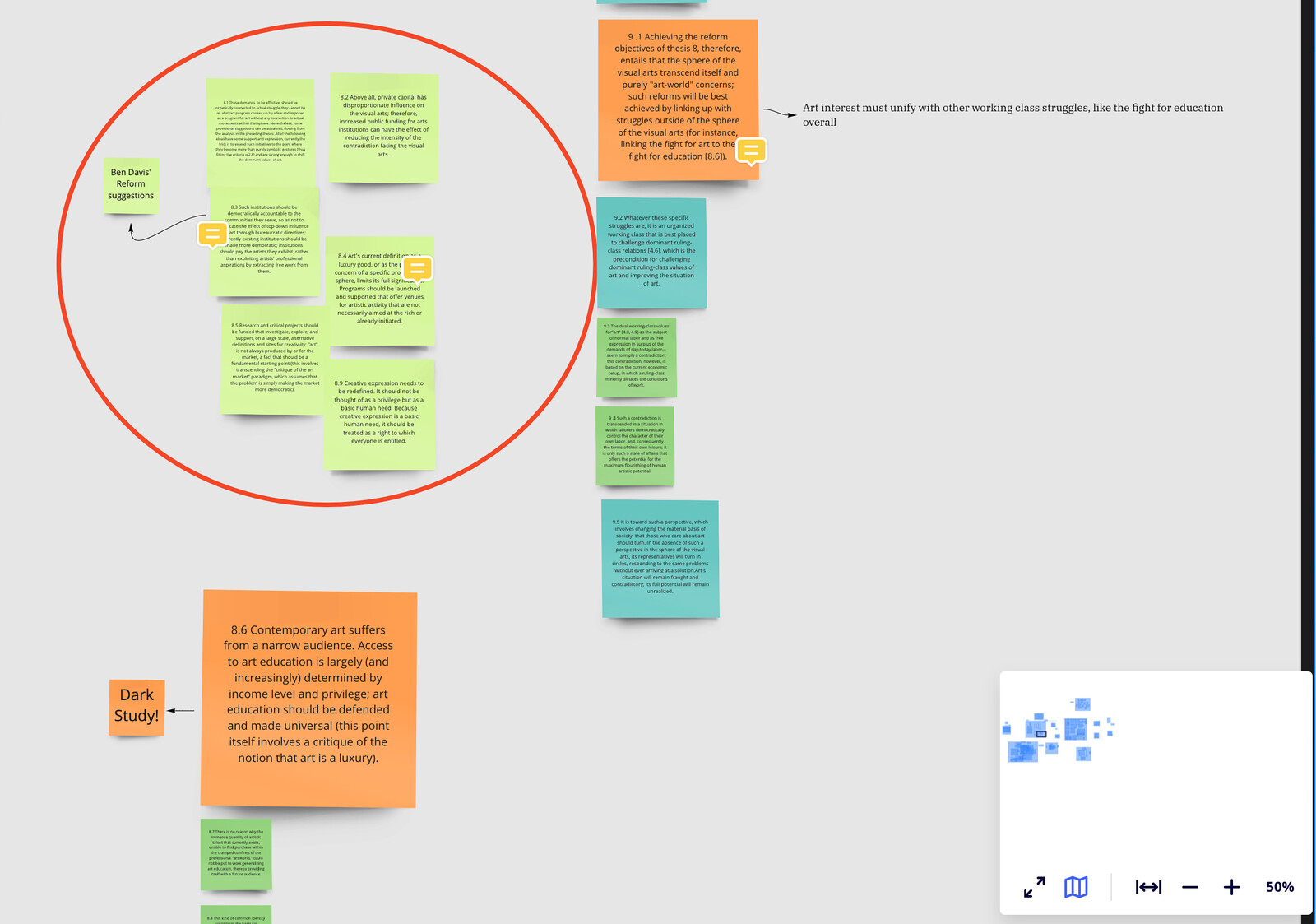

Dark Study hosts two courses in its first semester. “Art for Whom?,” led by Maloof, is an overview analysis of empire that addresses class while developing a working definition of imperialism. The course will end with students producing analyses of class’s influence on their lives and their art practices as a means of understanding their identities through access (or lack thereof). “Divergent I,” led by Cherry, discusses the art market and its influence on artists’ studio practices and how nonprofits funnel money and influence through cultural institutions, or “why artists make work, how that work circulates, and the multitude of ways where the needs of the artist and the desires of a market-driven art economy diverge. 6 These externalities are explored through a series of student-led presentations and responses to Andrea Fraser’s 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics, Martha Rosler’s Culture Class, Denise Ferreira da Silva’s Toward a Global Idea of Race, and Ben Davis’s 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, among others. Students have access to the whiteboard app Miro and are developing a sprawling map that traces nonprofits’ and major institutional boards’ capital and investments through exhibitions and museum collections. Though we expect more from those in positions that are supposedly meant to protect our cultural heritage, in reality trusteeship on American nonprofit and institutional boards is intended to keep the system in its current configuration as a strategic manipulation of the market, with the aim of using art and artists to circulate and concentrate capital. 7

Contextualizing the art market and the imperialist project as objects of study within the structure of an advanced art program has the potential to facilitate practices that incorporate institutional critique into studio work. This shift, decentering artistic practice away from solipsistic analysis of the self and towards an ecological examination of culture and its systems, is significant. Dark Study fuses aesthetics with an investigation of and critical relationship with the structures that aesthetics exists within, and in doing so, it seeks to enact a pedagogy informed by solidarity and intended to build community beyond those confines. This examination about circulation is further addressed by Dark Study’s advisors, each of whom addresses the market and the circulation of art in their own practices, writing, and curation: Sondra Perry’s It’s in the Game questions museum acquisitions and their role in representation and the depictions of subaltern histories; Jesse Darling critiques the Ballad of Saint Jerome and the hierarchies of dependency and compromise that it establishes; David Xu Borgonjon evaluates cultural artifacts and the orientalizing of Chinese culture and artists, specifically in his critique of Asian Futurism in “Continental Drift: Notes on ‘Asian’ Art”; Che Gossett has contributed writing to understanding trans cultural production and violence against blackness; and Serubiri Moses, cocurator of Greater New York 2021, has long-term curatorial projects like The Visual History of African Women’s Liberation Struggles (1989–present), which deals with historical narration, African feminist theory, indigeneity, and their depictions. Cherry and Maloof made recommendations to advisors about whom they felt would benefit most from advising, but ultimately the mentors picked their mentees. “We really thought about who actually needs advising, and so when we speak about something like quality of work it’s not a judgment of the work itself but more of where are they in their creative development,” Maloof clarifies. “We chose based on who, in having an advisor, would have a significant impact on their work.”

When evaluated as a whole—structure, ideology, and participants—it is clear that Dark Study as a replacement MFA is interested in developing visual artists who develop their practice as political entities and engaged critics of art-market institutions, scopic regimes, and cultural hegemonies. Because of its independence from endowment- and debt-backed programs, the school owes only its student. It presents a formidable anarchist/utopic engine: a free education that provides direct access to curators and critics working in the art world and an insurgent education that combines aesthetics with institutional and cultural critique. This critique, perhaps most radically, dissolves the individual liberal subject and replaces it with tentacular arrangements, collective thinking, and macroscopic pedagogical frameworks. As Moten says, “Like Deleuze, I believe in the world and want to be in it. I want to be in it all the way to the end of it because I believe in another world in the world and I want to be in that.” 8 Utopic beauty is and always will be fugitive. 9 Dark Study proposes a reform not only of higher education but of the culture and world itself in hopes of creating a new one and provides strength and solidarity in the spaces left to the divergent.

Lauren Berlant describes cruel optimism as “a relation of attachments to compromised conditions of possibility whose realization is discovered either to be impossible, sheer fantasy, or too possible, and toxic.” The cruelty of this false desire “is that the subjects who have x in their lives might not well endure the loss of their object/scene of desire, even though its presence threatens their well-being because the continuity of its form provides something of the continuity of the subject’s sense of what it means to keep on living on and to look forward to being in the world.” Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 24.

Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2013), 20.

See →.

See →.

In which Phillips writes, “In our space-time mapping of the future, however, rarely do we take account of where the future is, who has access to it, its plurality, and whether we are all accelerating at the same rate and pace into that future … The time dimension plays a crucial role in how people—particularly Black and poor people—are valued, treated, punished, or underserved by and within society.” Rasheedah Phillips, “Communal, Quantum and Afrofutures: Time and Memory in North Philly,” in Black Quantum Futurism: Space-Time Collapse II (Philadelphia Afrofuturist Affair, 2015), 10.

Caitlin Cherry, “Divergent I” syllabus.

“Governed with little or no democratic input or oversight, they (non-profit arts organizations) are part of a system in which public resources … are channeled to privately controlled organizations that operate with little public accountability; a system which … may serve to legitimize the economic inequality and privation that underlie so many of the social problems philanthropic organizations aim to solve.” Andrea Fraser, 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018), 31.

Moten and Harney, The Undercommons, 118.

Moten and Harney discuss the subversive intellectual’s perpetual fugitivity. Though the university is a place of “refuge” it is also a place that cannot “bear what (the subversive intellectual) brings.” She must “disappear into the underground.” Ibid., 26.