Museum stores and bookshops are in-between spaces. Visitors alight there after taking in an exhibition, perhaps to purchase a physical reminder of what they just saw; or they might meet up in the store prior to entry. Their usual adjacency to areas that do not require admission renders them semi-public, and as such, much like department stores, they allow for, and perhaps even encourage, a purposeless occupation of space. Under the auspices of consumerism, loitering can become browsing. In art spaces, however, lingering—being present—has the potential to become its own form of participation.

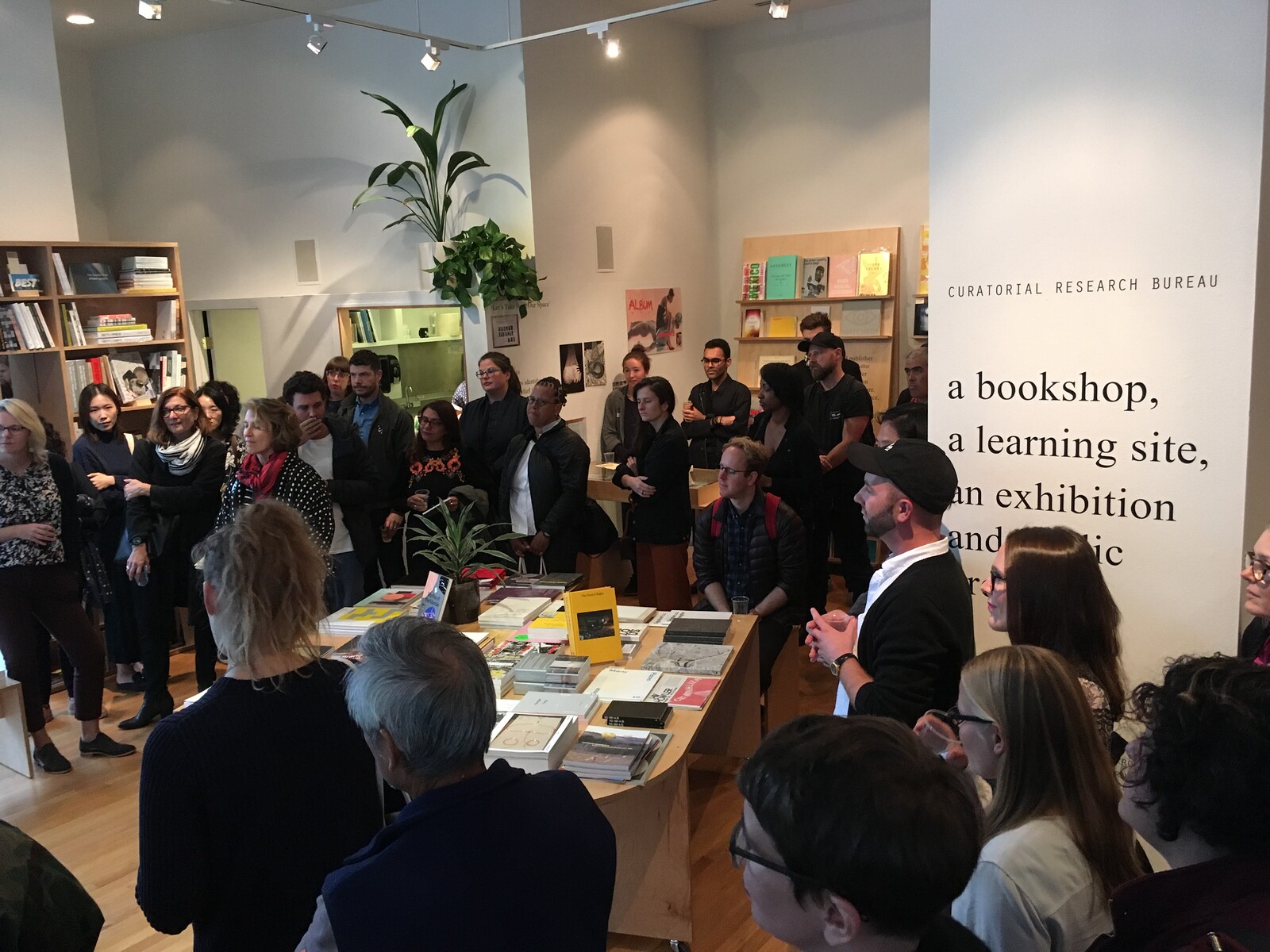

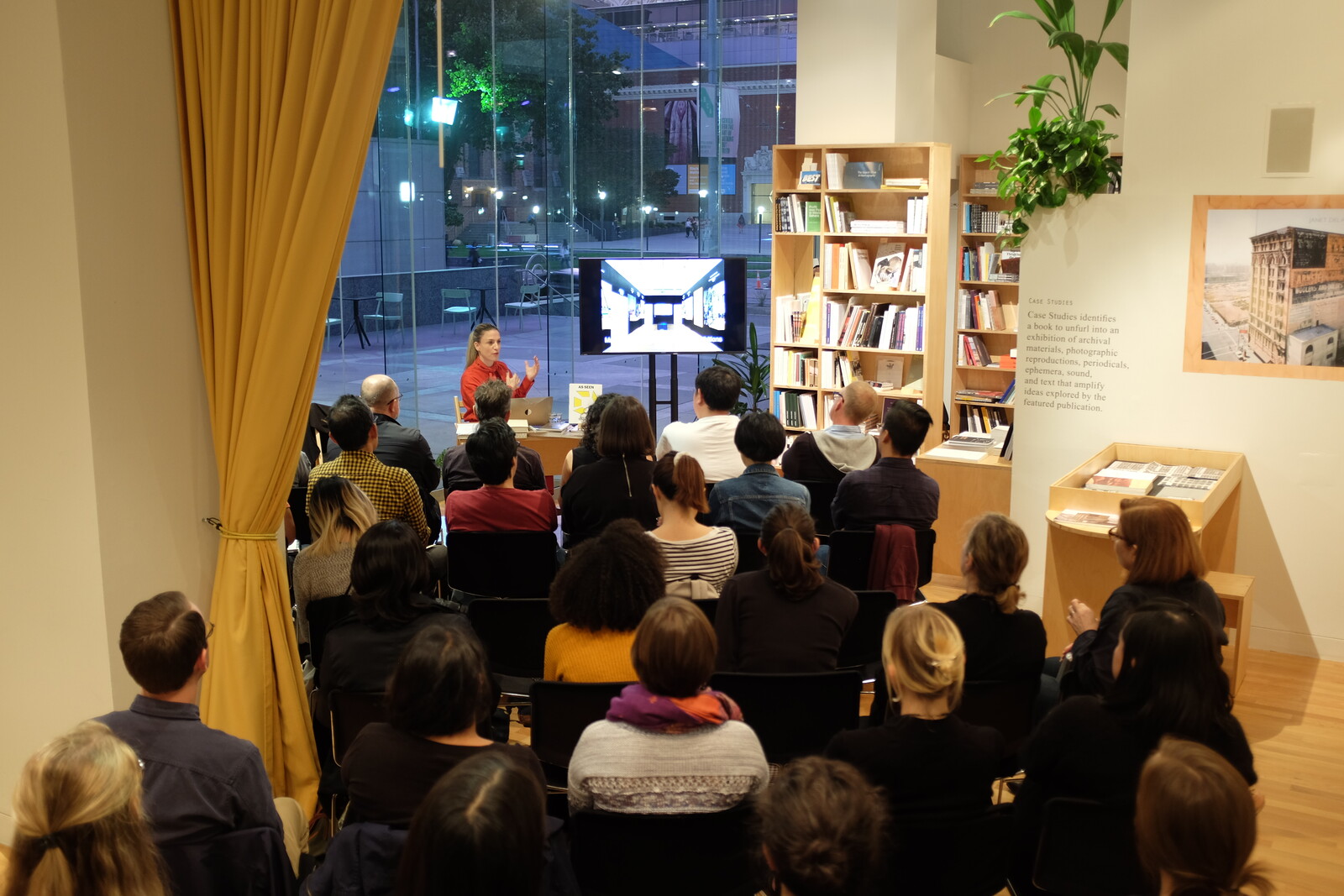

The Curatorial Research Bureau (CRB) can be easily mistaken for just such a space on a first impression. Just off Yerba Buena Center for the Arts’ airy lobby, by the building’s entrance, the glass-fronted corner space welcomes visitors. Suffused with natural light, its warm interior employs some of the hallmarks of the refined minimalist aesthetic that has become the lingua franca of boutique retail spaces around the world: Titles rarely encountered in Bay Area shops—provided through an exclusive arrangement with Berlin distributor Motto Books—are attractively arranged on unfinished wood shelves and tables. Lush potted plants provide an organic accent, a mustard velvet curtain some drama. The space’s very Instagram-readiness, handsome and inviting as it might be, lends it a familiar and slightly anonymous quality at the same time.

That CRB feels both expected, given its location, and slightly uncanny, given its recognizable appearance, is by design. It is indeed a shop, with regular hours and stock for sale. But, as implied by its administrative title, CRB’s purpose goes well beyond the book trade while still making strategic use of the museum shop’s medial status. As the primary hub of activity for the California College for the Arts’ Graduate Program in Curatorial Practice for the next three years, CRB hosts class meetings, various public and semi-public programs, and small exhibitions, while providing students behind-the-scenes access to the institutional infrastructure of YBCA. Launched in September 2018, CRB is an experiment in progress that aims to “reposition the Curatorial Practice program by projecting the pedagogy outside traditional walls of the academy.” 1 In speaking with faculty and attending some of CRB’s public offerings over the course of its first semester, the complications of “unit[ing] education and consumerism inside a contemporary arts institution”—which the bookshop itself embodies and holds in chiastic tension—have clearly been both anticipated and unforeseen. 2

CRB began as a practical solution to a common problem. When James Voorhies returned to CCA in 2016 to become dean of its Fine Arts division (he was previously deputy director of the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts from 2005 to 2006), the building near CCA’s main campus that housed the Curatorial Studies program was slated for a multiyear renovation. Rather than remaining in academic facilities under construction and near the noise of new construction or placing students at a further remove from local arts institutions by relocating the program to the same outbuilding in the waterside Dogpatch neighborhood where CCA’s other master’s classrooms and studios are housed, Voorhies saw an opportunity to build more substantial relationships between the Curatorial Practice program and those organizations. “There was a real absence of a solid connection between the institutions and [the program],” Voorhies said, echoing the sentiments of many personal acquaintances who graduated from the program and felt “isolated” or “cut off” from the larger Bay Area arts ecosystem as students.

To counter this disconnect, Voorhies reframed the Curatorial Practice program as “an institution within an institution,” with YBCA as a natural choice for host. Founded in 1993 as a non-collecting institution, YBCA has prioritized collaborative initiatives with other institutions while maintaining a longstanding interest in programming and artistic practices that are pedagogically oriented, in addition to performance, film screenings, civic engagement work, and visual art exhibitions, most notably the Bay Area Now triennial. 3 Voorhies cited a recent visit by social practice artist Suzanne Lacy as evidence of the synergy between YBCA and CRB: having previously discussed Lacy’s work and theoretical responses to it in seminar, students had the opportunity to speak with the artist herself about the pieces under discussion, as well as sit in on meetings with YBCA’s curatorial team and marketing department held in advance of a Spring 2019 survey of Lacy’s career, jointly organized with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), just across the street.

Voorhies, who also serves as chair of the Graduate Program in Curatorial Studies, is one of the primary forces behind CRB. Aside from the part-time bookshop manager who coordinates all shop logistics, he is its most regular presence. Voorhies sees the space’s identities as pop-up bookstore and learning center as manifold and complementary; the shop serves as both a form and a front, of sorts. The bookstore, as a “kind of exhibition,” in Voorhies’s words, has reoriented the Curatorial Studies program toward a potential public that is greater than the program’s prior academic surround allowed for. In turn, being based outside of CCA has provided graduate students and faculty with more opportunities to plug into and connect with its host and other nearby institutions. On a given day, the program’s six students might meet with professors while the store is open; members of the public can attend visiting lecturers’ talks; visitors can take in a tightly curated display of printed matter in the space’s dedicated exhibition vitrine, cheekily titled “Case Studies,” which will eventually be organized by students. Although Motto supplies most merchandise, with additional titles provided through Amsterdam’s Valiz Publishers and the Aperture Foundation, CRB’s involvement with other San Francisco institutions is apparent in the store’s stock. Voorhies cited “thirty or forty different kinds of consignment purchase agreements” with Bay Area artists or publishers, including Crown Point Press, Colpa Press, and Owl Cave Books. Local titles, such as Colpa’s SF Rave Flyers 1991–1992, which, as its title suggests, reproduces handbills from the golden age of the Bay Area’s techno underground, have been some of their best-selling items.

“The bookshop can perform differently depending on the situation,” Voorhies said, imbuing the space with an agency of its own, and a flexibility of purpose echoed in the space’s design by Nate Padavick, Voorhies’s partner. CRB’s furniture and interiors—twenty-four moveable, connectable modules—physically facilitate his longstanding interest in pushing the boundaries of a given institution’s capacity. Tweaking the function inherent to its form has been the motor behind the Bureau for Open Culture, the curatorial practice and framework through which he—and later, he and Padavick—produced exhibitions and programs for the Beeler Gallery at Columbus College of Art & Design from 2007 to 2011. BOC is listed as a producer of CRB (a bureau within a bureau, if you will), and many of the concerns BOC engaged with emerge through lines of the conversations in “Experience It.” This ongoing series of talks between Voorhies and visiting artists working at the intersection of audience participation and institutional intervention, such as Sharon Hayes, Martine Syms, and Jon Rafman, technically predates the opening of CRB but has since become a parallel discursive track and part of its programming. Unique to CRB is “AfterWord,” invitation-only follow-up discussions the morning after each artist talk meant to extend the conversation by moving it to more intimate surroundings.

The “AfterWord” session I attended the day after Simon Fujiwara’s presentation was halting at times, perhaps because of morning cobwebs or the artist’s tendency to talk at his interlocutors. Still, the mood was relaxed, especially in comparison to the tension that marked the previous evening’s exchange between Fujiwara and a much larger audience. This felt more like a discussion, even if the scheduled hour ended just as the conversational ice started to thaw. At the very least, it was heartening to have an opportunity for such a mixed group of CCA students, local artists, and arts administrators to gather outside the context of an opening, seminar, or Q&A session. The simple fact of coming into a different space seems to have had an energizing effect. The week prior, the past-capacity public seminar talk given by Amanda Hunt, director of Education and Public Programs at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, had the unexpected buzz of a reunion, which in a certain sense, it was: Hunt is a Curatorial Practice alumnus. Other guest speakers this semester, including critic and curator Barbara Pollock and Museum of Transgender Herstory founder and visual artist Chris Vargas, were met similarly warm receptions.

CRB’s dual-identity as a store and classroom, and YBCA’s central downtown location, certainly contribute to its accessibility. “People will wander into something that looks like a bookshop much more freely than they will something that looks like an exhibition space. It’s productive for bridging divides for who is coming to what sort of cultural spaces” said associate professor of Curatorial Practice Christina Linden, echoing a continuing thread of discussion in her class on the exhibition as form. Over its many lives, the space at YBCA that CRB now occupies has worked in this capacity before. Most recently, in 2017, the space held Sanctuary Print Shop, a workshop run by Sergio De La Torre and Chris Treggiari in conjunction with the Tania Bruguera exhibition “Talking to Power / Hablándole al Poder.” The year before that, it was a NASA-themed pop-up café built to coincide with an exhibition of Tom Sachs’s spacecraft sculptures. The space has also been something like the center’s albatross, sitting vacant for extended periods.

Faculty member Dena Beard, who is also executive director of the long-running San Francisco experimental art space The Lab, joked that holding class just outside the lobby of “a well-known art center” was “certainly more cacophonous” than on campus. But, the confusion that can arise when, say, a group of Salesforce conference attendees wanders into a discussion of Michael Fried, can also be generative—perhaps more so for the would-be customer than the student. “So much of the art experience is one of misrecognition, is one of confusing the boundaries and territories of what’s part of the consumer structure and out of the normative economic confines,” Beard elaborated. “I didn’t want people to be intimidated because we were having class; I wanted them to listen in and linger.” 4 More productively, conducting a seminar in what Beard calls, complimentarily, a “teeming fishbowl,” has necessarily meant that discussions more readily enfold what’s happening beyond the classroom. In the CRB’s first semester, this sometimes happened quite literally: the Marriott hotel workers’ two-month-long strike, held at two different properties just blocks away from YBCA, was still audible above the ambient background music playing at CRB on my first visit. Linden seconded the benefits of being open to incorporating voices outside a traditional curriculum in a seminar setting: “As an ideal, [CRB] does give primarily a sense of activity and urgency to the conversations we’re having that do feel like a real shift from the conversations we had on the CCA campus,” which, she noted, felt by comparison, “at a significant remove from anything that wasn’t theoretical.”

Providing a theoretical background, as well as an overview of the practical skills required by curatorial work, is the balancing act faced by any professionalizing program in the field. In addition to foundational coursework on the history and practice of exhibition making, CRB students, like Curatorial Studies candidates before them, will collaboratively develop, organize, and install a capstone exhibition at the Wattis at the end of their second year. Voorhies hopes that future classes will have the opportunity to design the thesis show in partnership with other participating institutions, referring to YBCA and the Wattis as this year’s “core samples.” Similarly, both Beard and Linden see the potential for CRB to allow students to pursue their interests beyond the exhibition form into, say, public programming or educational initiatives, which could be complimentary components of a gallery show. Conceptually, CRB can be understood as an attempt to provide greater transparency, pulling back the curtain on master’s-level curatorial education and putting the work involved in achieving that balance between the theory and practice of exhibition-making on full view. Practically, there are limitations, especially the extent to which student participation can influence YBCA’s programming and the degree to which students have access to YBCA’s decision-making processes, particularly as the organization is at a turning point in its identity as a presenting institution.

Over the last four years, YBCA has added event rentals and public-focused initiatives such as the YBCA 100 summit and awards and the YBCA Fellows program to its in-house and touring exhibition programming. There has also been a diligent courting of the tech and design sectors, as both audience and funder, through partnerships like the Market Street Prototyping Festival and the inclusion of design in this year’s iteration of Bay Area Now. These changes have occurred under the leadership of CEO Deborah Cullinan, whose tenure has overlapped with the ascendancy of San Francisco’s new tech economy, a cultural and financial sea change that has displaced, disenfranchised, or otherwise disenchanted many in the Bay Area’s visual arts community. 5 Whether these shifts in programming and audience engagement have resulted in YBCA “reimagining the role an art institution can play in the community it serves […] by using culture as an instrument for social change,” per its mission statement, is debatable. 6 The populism of some initiatives, like the YBCA 100 summit, have felt overly PR-driven. Other developments, such as instituting pay-what-you-can admission in a town where $20 is often the minimum cost of admission before special exhibition fees and hosting CRB and supporting new curators in the Bay Area, have been genuinely laudable

Voorhies indirectly described some of the other, larger external factors that might account for this slow shift in YBCA’s approach when I asked him what students might take away from the program: “Institutions worldwide are grappling with how to connect with audiences, especially as culture is dispersed through many different outlets—including the screen. Institutions are also grappling with how to balance this element of entertainment with a kind of cultural experience or intellectual experience with ideas.” One symptomatic example is the phenomena of pop-up “experience” spaces, so-called museums designed for Instagram that, as in Los Angeles and New York, have had a subtle warping effect on San Francisco’s cultural institutions. 7 This has been most noticeable in social media and marketing campaigns, but even some museum exhibition design has incorporated elements meant to hold the attention spans and net the foot traffic of audiences used to a point-and-click form of mediated engagement (material perhaps for another strain of “Experience It” discussions). Voorhies added that “curators—including educational programmers—are wrapped up into this rethinking or response to contemporary culture,” and hoped students’ experience of CRB leaves them better equipped to drive that discussion forward.

The extent to which curators will be involved in shaping YBCA’s response to these shifting cultural conditions remains to be seen, especially in the wake of a recent series of transitions at the senior curatorial level. Marc Bamuthi Joseph left his position as chief of program and pedagogy and lead curator of performing arts for a new role at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, in December 2018; Isabel Yrigoyen now serves as chief of program and pedagogy on an interim basis. Visual arts director Lucia Sanramon’s role at YBCA is now in an at-large capacity rather than the in-house position to which she was initially hired in 2015, which is now held by Dorothy Davila. These changes were preceded by the dismissal of lead film curator Joel Shepard in April 2018, along with the suspension of the center’s film program so that it could be “reimagined” and “fully integrated into our public engagement efforts and working in service of YBCA’s mission.” Both moves came as a surprise to many in the local arts community, including Shepherd himself. 8

That a professionalizing program for future curators is housed at an institution with so many curatorial vacancies, and that is currently reevaluating the role on-staff curators will play in the organization’s future, is striking, to say the least. The turnover has also been an occasion for students to have conversations, both formal and informal, with faculty about what they want from the field they’re training to enter. “It’s a shortcoming preparing everyone for a position that may not be a good fit for them,” Linden suggested. She cautioned that while the changes at YBCA might be representative of a point particular to the Bay Area at this moment in time, they are not indicative of the field at large. Still, there is much to discuss: “I’m trying to take the time to introduce practical concerns and talk about how they intersect with theoretical possibilities in the classroom, and I’m being very deliberate about that,” Linden said. Beard has taken CRB’s institutional adjacency as an impetus to ask her students to envision what sort of institution they want to be a part of, as well as how they can work to shape that institution into something better. After visiting various organizations nearby, including the Prelinger Archive, SFMOMA, and the Altman Siegel gallery, Beard had “a lot of conversations with [students] about different sizes of institutions, about institutional failure, but also about what we want institutions to be.” She explained that she challenged her students to build a support structure for each other within the program in order to “create agency for themselves and for each other to build the sort of institutions they want.”

Beard’s push to have her students enact what she half-jokingly described as “curatorial communism” is one example of how CRB has the potential to make good on the “research” portion of its name. By enlarging the frame through which curating is understood, the theory of curating becomes inseparable from its pedagogy; its pedagogy is entwined with its practice; and all are underwritten by an ethics. Curator and CRB guest faculty member Maria Lind provided a prescient sketch of this in “Active Cultures,” a 2009 essay for Artforum on “the curatorial.” Lind views curating as the product of a network of actors (artists, curators, institutional staff, the press), as opposed to the work of one institution or the vision of one individual, necessitating a rethinking of the concept altogether. “The curatorial involves not just representing but presenting and testing,” she writes. The outcome can be “a stirring of smooth surfaces, a specific, multilayered way of agitating environments both inside and outside the white cube.” 9 Though still in a way-finding phase, the CRB is a site where what it means to learn to become a curator is being presented and questioned, one that also holds the potential to agitate. Lind—who has been communicating with students via Skype since CRB’s launch and will be on-site at the end of March—returned to this language of collision and close proximity in an email exchange. In response to my asking if, nearly a decade on, the formulation of the curatorial she provided in her essay resonated with CRB’s activities, she remarked that, although viewed from afar, she thought CRB was doing interesting things in terms of “widening the range of contact surfaces between contemporary art, curating, and other fields and people.” 10

At the end of “Active Cultures,” Lind notes the practical and professional stakes of this expanded contact: “Creative thinking is needed to create professional opportunities—but also to torque the profession itself.” CRB, as an inter- and intra-institutional entity, is in a unique position to exert slow pressure on the institutions that support it. In doing so, it has the potential to shift the terms through which future art professionals consider their roles and the kind of institutions they choose to work for or, to Beard and Lind’s points, will work for them. But, as Lind pointed out elsewhere in her email, such shifts come about slowly: “These things take a long time and require a lot of ‘massaging’ of various stakeholders, including potential conversation partners.” Such a time-scale might be at odds with the administration and mandate of a master’s program, or the built-in schedules and unknown future strategic timelines of a host institution that, like YBCA, is also actively reevaluating its current operating structure and programming. Questions of time are also, of course, tied to questions of finance.

Conceived of as a solution to a short-term problem, CRB’s limited lifespan is, to some degree, conditionally at odds with the development of this potential, even as its conceptual framing and flexible presentation mines a certain of-our-moment cache from its temporariness (It’s a pop-up shop! It’s a pop-up classroom!). Perhaps, as a trial balloon, CRB can provide a useful sample set of data with which the Curatorial Practice program and CCA can make longer-term recommendations for how such inter-institutional partnerships can be both sustainable and semi-autonomous. But might other alternatives be available? Rather than Voorhies’s interpretation of CRB as “an institution within an institution,” Beard understands the program as “parasitical”: CRB and its students are, she said, “embedded in the organs of the thing,” an advantageous space. Following Lind’s call for creative thinking, what would it mean for CRB to embrace the full potential of this internal position? Rather than engage in a symbiotic relationship of reciprocal convenience with YBCA, or whichever institution it collaborates with next, what would it mean for CRB to be truly embedded, and to have a real stake in shaping the longer-term priorities and programming of its host? Toward the end of our conversation, Beard sketched out one possible outcome of following this line of thought, in which the CRB eventually subsumes the Curatorial Practice program altogether. In lieu of being managed and overseen within CCA’s entire academic apparatus, what if, she suggested, CRB were to become an entirely student-directed and student-driven initiative, in which Curatorial Practice students develop curricula, decide which organizations or institutions to partner with, and determine how they would make use of CCA’s resources as well? While such a radical vision is likely impossible to implement in current formal educational structures, it is worth holding onto as a lodestar, especially if CRB is to make good on its intention to provide an alternative pedagogical and institutional model. As Lind wrote at the conclusion of her email: “A place like CRB can foster discussions around what it means to work with curating, and to work curatorially, and as a consequence, the students will be familiar with methodologies beyond what the art apparatus is asking for today. There are other ways than that of the ‘apparatchik.’”

—Matt Sussman

See →.

Curatorial Research Bureau Dispatch, Issue 02, October 2018.

Notably, Escuela de Arte Útil, an initiative by Tania Bruguera profiled for School Watch in 2017, and the Momentary Academy, a project organized in 2005 by the late social practice artist and CCA professor of Social Practice Ted Purves for Bay Area Now 4, in which artists led free classes for the public on a variety of subjects, from cooking as cultural exchange to spoken word performance, in a range of formats, from unique workshops to weekly meetings.

Based on feedback from staff and students, Voorhies has decided to move spring class meetings to Mondays, when the store is closed, to provide them with a less disruptive experience and full use of the space.

Many articles document this phenomenon, but Christian L. Frock’s “Priced Out: New Tech Wealth and San Francisco’s Receding Art Scene” for KQED Arts is a good place to start. Conditions on the ground have not changed much in the five years since its publication. See →.

See →.

The Museum of Ice Cream and the recently shuttered Candytopia, a competitor, were both walking distance from YBCA.

The turnover at YBCA coincided with a period of shifting or downsizing of curatorial roles at other local institutions, including the San Francisco Art Institute’s Walter and McBean Galleries and the diRosa Center for Contemporary Art. See →.

Maria Lind, “Active Cultures: Maria Lind on the Curatorial.” Artforum 48, no. 2 (October 2009).

Email with the author. January 20, 2019.