Since Jenny Jaskey became director of the Artist’s Institute at Hunter College in 2013, writers have become central to its programming. More than just commissioned respondents to featured artists, writers have been the subjects, organizers, and agents of exhibitions: in 2015, the Institute hosted an exhibition by Fia Backström that included ephemera from poet Eileen Myles’s 1992 presidential campaign; in 2016, it offered an innovative retrospective of Hilton Als’s work across mediums, mixing memoir, portraiture, and criticism; and in 2017, Benjamin Kunkel worked on a book about eco-socialism while he was a fellow there. For its fifteenth season, which ended in December, the Institute deepened its involvement with writing through workshops and lectures, replacing its usual exhibition programming with a series of events. The Writing and Talking series involved novelists, theorists, critics, poets, painters, and professors—Percival Everett, Dan Fox, Mary Gaitskill, Rivka Galchen, Wayne Koestenbaum, Ben Lerner, Fred Moten, Stefano Harney, Maggie Nelson, and Sasha Frere-Jones—in accordance with the Institute’s mission to support a “more expansive construction of the term artist.” Jaskey’s selection highlighted the generative possibility of hybridizing and challenging fixed authorial roles through a dazzling array of improvisatory, spontaneous, historicist, tragicomic, analytic, and collaborative tactics. The series’ flexible structure allowed for contingent results, less the professionalization of an MFA program and more the looseness of a salon.

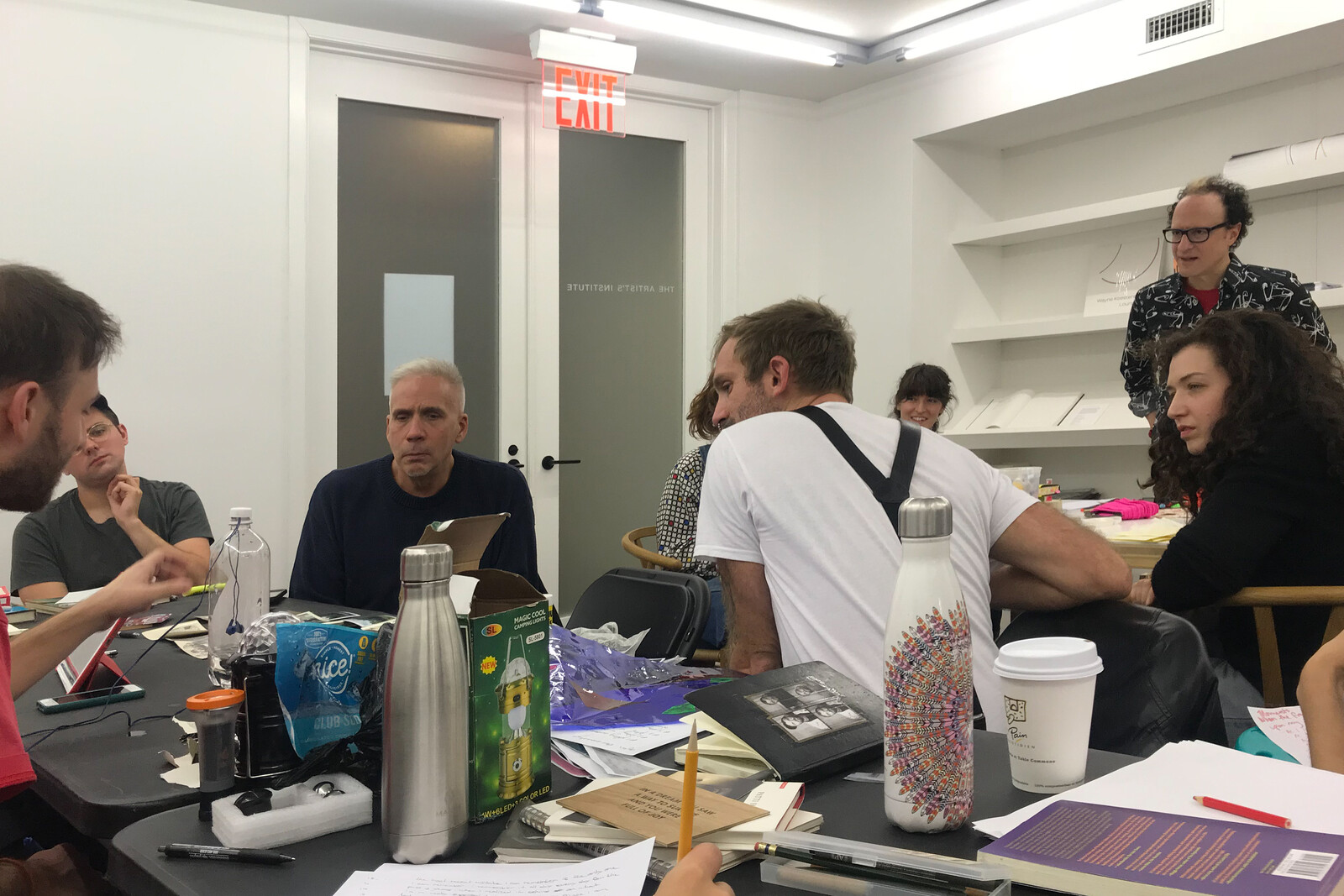

Cross-pollination occurred among the seminar, the workshops, and public discussions, and roles reversed as well, as Jaskey said: “Outside of art school, it’s a rare thing to sit around a table with your peers, to talk about work in progress, and to get outside feedback. Several of the participants who teach in art schools and have mature practices told me how refreshing it was to get to be students for an afternoon.” The free workshops allowed visual artists to refine and develop texts that would be part of, or adjacent to, their work, and art critics embarking on works of fiction were afforded the opportunity to radically develop outlines and revise texts at the level of the sentence. In tandem with the series, Frere-Jones led a graduate seminar for Hunter College students that looked at multiple forms of the essay. The gallery, meanwhile, had no exhibited artworks—seemingly mimicking the blank page, the site of encounter with writer’s block. Rather than resisting the block by progressing towards a predetermined outcome, the workshops approached impasses in writing as stimuli for precociousness, blankness, and the limbo in between.

Given that the Institute was founded in collaboration with the Department of Art and Art History at Hunter College, the move to prioritize literary arts and composition raised the question: does the writer’s invitation to the artist’s space dissolve, flip, resolve, revive, or fluff the verbal-visual binary? Rather than a simple answer, various methods of deformation and continuity were proposed, often accenting the role of chance. As Wayne Koestenbaum noted in his workshop, “Aesthetic practice of any kind fertilizes accident. Without a frame that isolates the ‘art object’ and sanctions its existence, there’s no possibility of stumbling across an exit from the claustrophobia that otherwise overwhelms a maker.” Similarly, in her talk and workshop, Rivka Galchen explored narrative framing devices and the pleasure of finding genre antecedents to formally experimental works and homed in on how reusing tropes can indirectly address themes that would otherwise be inaccessible to the writer or artist.

Dan Fox pushed the visual-verbal impasse to metaphysical planes in discussing his book Limbo, which makes a case for being stuck and questions progress, productivity, and growth. Fox praised anti-teleological gestures, stating in the introduction to his talk, “Questions will be asked. Answers will be stumbled over in the dark and cursed at.” Writer’s block and the limit were suited to biblical allegory, as when Koestenbaum referenced Alphonse de Lamartine’s maxim from Méditations Poétiques, “Limited in his nature, infinite in his desires, man is a fallen god who remembers the heavens.” In his workshop, Ben Lerner questioned the tacit assumption that art writers are secondary supplements to the artwork—necessarily more enthusiastic about the object described than the artistry of their writing. He closely edited the group’s texts to correlate visual form with verbal information. For their discussion “All Incomplete,” Fred Moten and Stefano Harney presented a new essay, “The Ante-Heroic,” which deconstructs the role of the monumental hero and analyzes the social possibilities of Wall of Respect, a mural in Chicago painted in 1967 by the Visual Arts Workshop of the Organization of Black American Culture. In the talk, as well as in their workshop on “deviant complicity,” Moten and Harney explored non-individualistic redefinitions of heroism—a deformation of the monumental through what Moten described as “ongoing haptic social poiesis.”

A performance of Hollis Frampton’s “A Lecture” and a conversation between filmmaker Bill Brand and philosopher Christoph Cox provided a structuralist reflection on spectatorship—the half-dark limbo of film audiences and students gathered in classrooms. Brand, Frampton’s archivist and former student, reenacted “A Lecture,” with a recording by artist Lucy Raven, in the same classroom where the piece was originally presented in 1968. Frampton, who taught film and design at Hunter College from 1969 to 1973, wrote an instructional score for presenting “A Lecture”: a performer plays a recorded monologue, turns on a 16 mm projector (without film), and uses a sheet of red cellophane, a pipe cleaner, and their hands to block the light. This version, like the original, ironically inflated then deflated the didactic function of the artist-lecturer, who demystifies the shadow plays of cinema’s “generic darkness” of illusory stardom and phantom part-objects. Frampton’s meta-mediation offers a paradoxical way to deal with film’s limits: “So if we want to see what we call more, which is actually less, we must devise ways of subtracting, of removing, one thing and another, more or less, from our white rectangle.”

Like Frampton, Koestenbaum generated sensory boosts from subtractive erasure. In his workshop and talk, he orbited the verbal-visual limbo through paint, poetry, prose, and piano. Koestenbaum improvised half-sung soliloquies with piano, even into the Q & A. He free-styled riffs on Milhaud, Verdi, Donizetti, Brahms, and Lutoslawski, while voicing sex stories, childhood memories, and theoretical musings. His workshop explored the generative tension produced by preserving the lens of solitude within collaboration—a public extension of his mostly solitary trance work—through Fluxus-inspired exercises that enabled reflection on the shift of focus from tedium to curiosity. He also revised several truisms on improvisation with his own quips—“Sometimes you need thirty thoughts to come upon the ‘first thought, best thought,’ with its attendant feeling of accidental quickness”—and provided a vivid description of the interplay between block and drive:

How to achieve freedom from hindrance through confrontation with the felicitous, blissful, detachment that turns the “mere doodling/journaling” into form? Establishing incongruity, contrast, suspense, synchronization, non-synchronization. When does a bird’s-eye-view of form kick in, so you can see posthumously and retroactively? Do we then make alterations for the stranger, the archive, or the void?

Koestenbaum’s enigmatic questions and blending of roles manifested the Wildean ideal of the critic as artist, making, in turn, the lecture or workshop an artwork—a capricious counterpart to Frampton’s “A Lecture.” Maggie Nelson, who closed the Talking series with Lerner, described to me how Koestenbaum’s “omnivorousness” and “dedication to art as weird, liberatory practice” influenced her genre-defying writing.

In an age of esoteric specialization in the academy, Wayne stands as an example of how one might gracefully navigate the sometimes disparate worlds of psychoanalysis, art criticism, film criticism, literary criticism, biography, poetry writing, fiction writing, cultural critique, political inquiry—and, more recently, painting, video art, and live performance … The very fact of him once gave me an abiding image of what I could aspire to do and be in this world; as Wayne’s own work expands, always deepening and reinventing the possibilities for being, his inspiration to me expands as well.

In a similar fashion, the Institute assembled a Wildean season, an apt departure from curatorial norms. For Jaskey, the importance of the season was its “strengthening of the ties between writers and visual artists” and “making these relationships visible.” By selecting writers who bend the categorical distinctions between fields and mediums, the season emphasized the mutable capacity of the exhibition space. Without neat resolution, a spectrum of ways to underscore impasses in writing were tested. Works were not intended to be categorically improved—as Koestenbaum put it, “The log and sum of moods” when writing does not necessarily “equal the value of the work.” The marking of an impasse was positioned as a stimulating condition for art when other options are vanishing, reminiscent of Barbara Johnson’s idea that literature’s ethical potential comes from being “the place where impasses can be kept and opened for examination.” 1 By not delivering the artwork as objective-correlative, literature’s impassability can be encountered. The flexible character of the Institute—its broad mission, its orientation towards the artist and writer, its relative autonomy from the college—make it a uniquely privileged site to thematize and explore the difference between experimental practice and specialized disciplines. As higher education’s support for the humanities and composition dwindles, the Institute’s fifteenth season encouraged a resurgence of attention to literary and art criticism as a form of expression, rather than just a mnemonic device to aid cultural observation.

—Felix Bernstein

Barbara Johnson, The Feminist Difference: Literature, Psychoanalysis, Race, and Gender (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), 13.