While listening to French economist and Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art faculty member Yann Moulier Boutang describe the rise and impact of knowledge as a factor of production in contemporary economies, I knew that evening I would be given my share of three kinds of wine, to borrow a metaphor of Moulier Boutang’s describing the nature of finance and the role of speculation: “old wine in new bottles,” “new wine and new bottles,” and “new wine in old bottles.” A new kind of capitalism had emerged, the author said, one created by the rise of new digital technologies.1 Termed “cognitive capitalism,” the hypothesis is not new to the Saas-Fee; in fact, it has provided a conceptual foundation to the program since the roaming academy’s 2015 inaugural session. Cognitive capitalism assembles a complex web of practices that address the intelligence produced by the brain and computing power, and their collective impact on the physical world. Different strands have been identified over the years, primarily in Italian and French academic circles, such as Catherine Malabou’s concept of plasticity and the possibility of a plastic ontology, and the Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art’s curriculum has been driven by a desire to understand cognitive capitalism’s various threads. Precarious labor, post-Fordism, attention economies, artificial intelligence: all concepts and realities that international creative communities have negotiated with for years. Contemporary art and its producers have been clearly implicated by a labor embedded in the “factory of the brain … where the machinery of the brain takes on added importance as a locus of capitalistic adventurism and speculation.”2 Although long-winded in kicking off the 2017 program, Moulier Boutang affirmed that art and cognitive capitalism had been bedfellows all along, sharing dangerous connections and new subjects. I left the lecture physically exhausted but mentally stirred by a provocation from one of Moulier Boutang’s slides: “Could contemporary art use cognitive capitalism as a means to foment a new critical subjectivity? Is another collective possible?”

Founded by artist and theorist Warren Neidich, who serves as codirector with the art critic and poet Barry Schwabsky, and until recently, with Lisa Bechtold as program coordinator, the Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art (SFSIA) is a Berlin-based, three-week-long art and philosophy intensive. It landed in the German capital in 2016 after a brief stint in 2015 in Saas-Fee, Switzerland, the resort town in the Alps where the European Graduate School (EGS) administers its master and doctoral programs in its Division of Philosophy, Art & Critical Thought. Schwabsky, who will lead next summer’s intensive under the tentative title of “Praxis and Poesis in Cognitive Capitalism,” described his desire to start a school as a response to a “crisis” across the sector wherein art academies are “controlled by administrators—not by faculty—an ever-expanding layer of bureaucrats who are removed from the real needs of students and the realities of teaching and research.” Schwabsky proceeded to team with Neidich, who he knew had simultaneously developed a desire for a retreat and would turn plans into action.

And so, the SFSIA was born as a parallel program to the activities at EGS that summer in Saas-Fee. The SFSIA had no formal connection to the European Graduate School and maintains the moniker today simply as a nod to its origins. In Saas-Fee, theorists Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Armen Avanessian, Anke Henning, Hito Steyerl, and Gerald Raunig were joined by EGS faculty like Philip Beesley, Benjamin Bratton, Keller Easterling, Metahaven, Patrick Schumacher, and Sanford Kwinter to create a nightly lecture program that usually concluded with heated discussions at the local bar. Under the banner “Art and the Politics of Estrangement,” participants were invited to consider how an artistic ostranenie, or defamiliarization, could reveal the underlying presuppositions about emerging discourses and metaphysical problems in a range of fields from media theory to neuroscience, from speculative materialism to poetics. “The process or act of endowing an object or image with strangeness by removing it from the network of conventional formulaic, stereotypical perceptions and linguistic expressions,” as described on the SFSIA website, fueled the attendant debates around the Anthropocene and accelerationism.3

In 2016, the institute relocated to Berlin for a program dedicated to “Art and the Politics of Individuation” held at the contemporary cultural production platform Import Projects. It made headway into cognitive capitalism through the work of Gabriel Tarde and Gilbert Simondon and considered, among other topics, metadata, mimesis, and immaterial labor. This year’s iteration, “Art and the Politics of Collectivity,” took place daily at the notable art revue Spike Art Quarterly’s event space in Berlin’s Mitte neighborhood. Neidich, currently a professor of art at the Weißensee Kunsthochschule Berlin, explained in correspondence that the urge to move to the city was stimulated by the lack of an art context in a village in the Swiss Alps. The choice for a metropolis was, on one hand, personal (he lives and works in Berlin and Los Angeles), and on the other vocational, in that the city is one of the best companions art and philosophy could have, where a burgeoning critical community thrives. Cosmopolitanism was also one of the session’s themes. Indeed, location counts: Spike’s proximity to the historically avant-garde theatre Volksbuhne (literally “the people’s stage”), currently under fire for its new director Chris Dercon, who intends to make it into a contemporary art center thus endangering the radical sensibility that has long characterized the theater’s mission, provided primary insight to the protests against the theater’s leadership. As a member of the institute’s faculty for the last two years, my feeling is that the SFSIA is an attempt to condition and nurture this radical sensibility that has—until recently—characterized Berlin.

“Art and the Politics of Individuation” and “Art and the Politics of Collectivity” fit under the overall aegis of cognitive capitalism, yet one that abides with the idea of an Art Before Philosophy Not After, a work on paper by Neidich, which casts art as a mutation of the “political-spiritual-psychological relations that constitute the cultural field” rather than a representation.4 The 2017 program bulletin echoed this call, stipulating that “curating, art production, and writing act to mutate the socio-political-cultural habitus requiring philosophy and theory to continually retool themselves in order create new forms of understanding.” How this is articulated can best be understood by another angle of the program that impelled its theoretical guild, but more on that later. “What has become obvious to me is that in our moment of cognitive capitalism in which the brain and mind are the new factories of the twenty-first century, forms of activism invented during industrial capitalism like refusal to work, absenteeism, and labor strikes are no longer up to the task,” Neidich said. “A new dictionary of terms needs to be invented to combat precarity, 24/7 labor, valorization, and the financialization of capital. The mission of the institute is to investigate how art might function to create new forms of agency against the new and evolving socio-political structures now at hand.”

Neidich’s work clearly mutates conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth’s collected writing “Art After Philosophy and After” as a mode to create spaces of deregulation and breath. It is not uncommon for Neidich to include his own work in the institute’s pedagogy or how he deems it fit for current debates. He explains, “The interest I had cultivated earlier in my Blow Up: Photography, Cinema and the Brain, and Cognitive Architecture: From Bio-politics to Noo-politics; Architecture & Mind in the Age of Communication and Information between political and material ontologies of the brain was always an essential component of the curriculum and acted like a delicate filamentous spiderweb capturing and connecting all the various subject matters.” A range of criteria influences who is invited to the school, be it their professional history with Neidich (for example, Barry Schwabsky and Hans Ulrich Obrist contributed to the artist’s 2005 catalogue Earthling), their expertise in the field of cognitive capitalism and how it is renewed (often represented in the ongoing series of texts he edits at Archive Books on the subject), and, last but not least, student evaluations, a casual factor for asking lecturers to return.

With modules that change every day, morning and afternoon, and an evening public lecture series to which faculty contribute, the program packs abundant, deep learning into its three weeks. One morning, philosopher and media theorist Matteo Pasquinelli worked with students on two of his essays: one on the Anthropocene, and the other on artificial intelligence. I witnessed how he traced labor as a source of information and intelligence that gives form to energy. Carbosilicon machines and cyberfossil capital were sketched “in order to rethink social autonomy of energy and information.” A complementary module by the Italian theorist Tiziana Terranova followed Pasquinelli’s and mapped “a neo-monadology of social production,” with consideration given to social media platforms. In discussion with students, she aimed to produce a new kind of diagram of what techno-collectivities can do. Probing another angle of the commons the next day, Franco “Bifo” Berardi, the only thinker to participate in all three summer institutes and one whose many subjects link with cognitive capitalism, questioned the meaning of the word “truth.” By recounting twenty years of “media-artivism” of the International Errorista, he spoke to the problem of error in the history of philosophy. To absorb, assess, and assimilate each module, as they arrive in layers, is the test at SFSIA, and students are encouraged to question and problematize their theoretical or creative practices as the intensive unfolds.

Beyond the institute’s work with cognitive capitalism, curating also serves as an agent of inquiry. Curators and local talent from the Berlin art community are invited to talk about their individual practices. In 2017, the program hosted “New Positions in Curating,” a day-long symposium featuring Heidi Ballet, Mathieu Copeland, Nikola Dietrich, Jens Maier-Rothe, Ludwig Seyfarth, and Anuradha Vikram. Over the years, prominent figures in curating, such as Hans Ulrich Obrist, Defne Ayas, Julieta González, Joshua Decter, and Raimundas Malasauskas have filled the bill, often not conforming to the concurrent themes and instead discussing current projects. Whether this created a dissonance or richness in the curricula is in the eye of the beholder. When asked how engagement with the curatorial might complement or rival the firm adherence to cognitive capital in the theoretical side of the program, Neidich clarified, “I wouldn’t say that we abide by a modernist ethos of separating and isolating forms of artistic labor into three such categories but rather understand it in a non-specific and distributed way. Curating is no longer an isolated practice but borrows from models of artistic performance, installation, and production, as well as other forms of knowledge production like anthropology, sociology, and politics. Can you really separate the curatorial practices of Hans Ulrich Obrist or Raimundas Malasauskas from artistic production?”

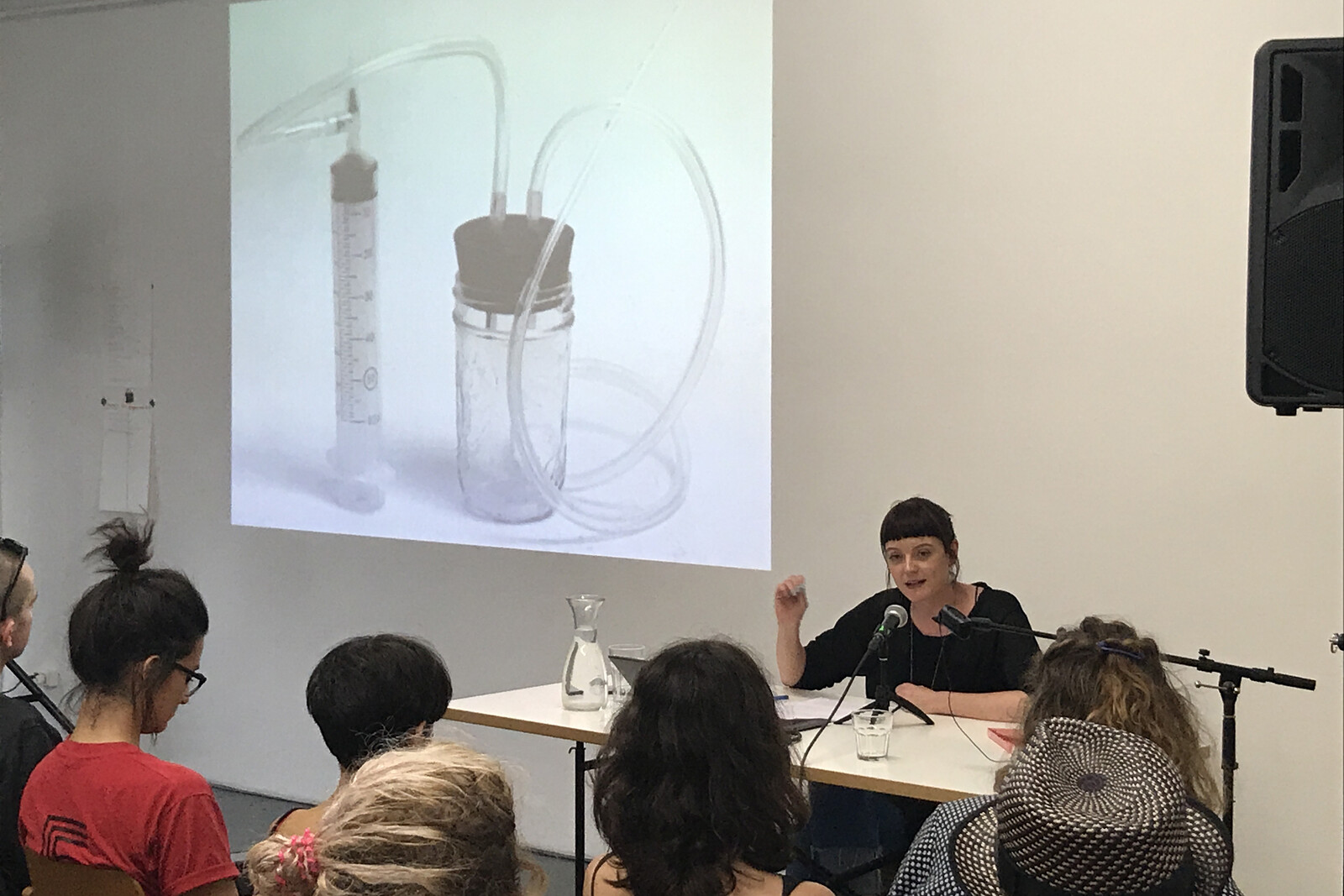

Indeed, the question of divisions between modes of cultural production influenced my lecture at SFSIA through a discussion of the ontological provocations: “What is research? What is artistic research versus fine art or research? What is unprecedented artistic research? Where lies the theoretical?”—questions that have been brought to the forefront by scholars like British aesthetics professor Michael Biggs. In my presentation, they were positioned within an inquiry on material uncertainty, ingestion, and embodiment. They were employed as a means to reveal (obliquely) the tools I use in field research on clays with forgotten origins, largely centered on geophagy, for the work “Elusive Earths,” which I co-curate with philosopher of science Lorenzo Cirrincione. In an effort to outline my process, I teased out techniques and methods vital to research and experimental sociological inquiry. At the end of the lecture, Neidich and I discussed the tensions between art and artistic research, which opened to a debate on the floor. After each talk at SFSIA, speakers are engaged in a question-and-answer interview determined by the students’ participation.

SFSIA receives more than one hundred applications each year from prospective students around the world and hosts an average of thirty-five students with a typically balanced female-male ratio (2017, however, was inexplicably more female). The program is advertised at $2,000 USD but many students receive scholarships or reductions. Most of the students I met were concurrently pursing MFA or PhD degrees in curating, media studies, cultural studies, or anthropology or were artists looking to sharpen their theoretical prowess. Most students conversed in philosophical and social theory vernacular with ease, skills put to good use by Berlin-based art historian and curator Antonia Majaca, who marshaled a kind of forward-thinking collective incantation one afternoon. Majaca, who is a talented orator and adventurous thinker at the interstices of art and politics, framed the module as a way to establish a “temporary community of intensity” by intentionally bringing divergent semiotic environments and perceptual modalities into contact with one another. Majaca began by asking each student to describe what excited him or her intellectually most at the moment. Each proceeded to provide one pivotal work or concept to the pool of keywords. She later improvised a lecture based on the keywords collected. Then, the students reflected on some of her propositions. These were later channeled into her evening lecture in the form of intertwined histories of psychoanalysis, cybernetics, and social paranoia in full turn.

The ambition of the program is further amplified by non-obligatory side programs, such as this year’s tribute to the late British cultural theorist Mark Fisher, and shorter intensives, such as the one to be held at the Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles, next year that will focus on the role that art plays as a generative and emancipatory force in our lives. That program will be coordinated with the MA Aesthetics and Politics program at the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia.5

But, more importantly, the student’s exhibition is a core aspect of the program. In 2016, exhibition work was carried out in a vigorous one-week installment at Kunstverein am Rosa-Luxembourg-Platz, where students were urged to “create a work that reflects their time at the course,” coordinator Lisa Bechtold said. With no studio attached to the program, students were required to withstand the challenge and put their noses to the grindstone. Bechtold, who oversaw their needs, did not consider this a problem but rather an asset and a characteristic of the intensive spirit of the program. When I jumped on the bandwagon one week before the exhibition’s opening to dialogue with students about their aims for the exhibition, there was a definite sense of tension about how to wrestle with time, decision making, and installation plans. This dampening effect might have urged the shift to an evolving, transforming, and at times immaterialist set of works focusing on the “Artist as Editor.” The notion in the exhibition at Spike was to play with the idea of taking away, or deletion, or rearrangement. Over drinks at the Spike bar where students and faculty mingled after talks, I witnessed works accumulating on the wall. One student drew a finger-pointing outline within a sea of printed and highlighted texts. Like a “living archive,” a sense of intervention, or explicitness, was at play in this participant’s artist-editor commentary. Another piece, or intervened text, perhaps by the same artist, displayed Martin Heidegger’s The Question Concerning Technology, annotated with a sideline reading “total immobilization,” and “Heideggerrrr” grafittied at the top.

Mexico City–based artist, art critic, and SFSIA III participant Kimberlee Córdova described the course as “saturating” and “breathlessly intense,” and arrived in Berlin not expecting the difficult practical details that come with spending a month in the city. (Many of the students, including herself, had trouble securing lodging, whether because of the exaggerated increase in summer tourism or Berlin’s current housing crunch.) She was attracted to the program for its caliber of speakers and mentioned that although the internet eliminates the “need” to travel to understand concepts and movements, there is a certain regionalism that does tend to dominate the conversations in her base city, thus allowing local context to dominate creative discourse. “The local housing bubble and attendant crisis ended up being the focus of my piece for the final exhibition, a mural loosely appropriated from a real estate developer’s office called New Estate that occupies a former art gallery in Prenzlauer Berg,” she explained. The work also invoked the program’s consideration of cosmopolitanism, elite culture tourism, and a global economy fixed for the privileged 1 percent as threats to a political collectivism founded on universal rights. “I painted the mural with Campari as a way of connecting what is effectively a colonial practice of speculation in the form of foreign investment to commodity housing that is driving these real estate bubbles with other colonial industries. Campari was until recently colored with carmine, or a dye made from the cochineal insect indigenous to Oaxaca. Cochineal is an example of an internationally traded commodity whose market value ballooned through colonial Spanish ‘repartimiento financing.’ Ultimately the piece was meant to be a way of ruminating on how cities promote themselves to attract speculation under the banner of ‘development.’ For example, a decade ago Berlin’s mayor Klaus Wowereit used the phrase ‘poor but sexy’ to sell the image of the city to tourists and investors alike. With the once-every-ten-year concurrence of Documenta, Skulptur Projekte Münster, and the Venice Biennale as context to the 2017 Saas-Fee Summer program, a [Campari] spritz recast as apocalyptic sunset seemed a relevant metaphor for thinking about the dissonance that arises from the schism between the privilege of art tourism and the various crises playing out in Europe.”

Valentina Sarmiento Cruz, a sociologist from Mexico and recent graduate from the New School for Social Research, New York, applied to the program for its emphasis on “collectivity,” sensing its obstacles and possibilities as a common thread in her previous projects and the ones ahead. The way that SFSIA correlated matters of collectivity to art was the defined challenge in its call for applications: “In a world in which we are more and more connected with the help of computational machines, what happens to our sense of collectivity? Can we, in our moment of cognitive capitalism, with the brain and mind as the new factories, find a place for the displaced body? Are we becoming less empathic? Is the accelerated change brought on by new digital technologies too rapid to become accustomed to?” Collectivity is about struggle. And one that can lead to positive outcomes, as Sarmiento Cruz notes. She stressed how the group would toy around with critical tools, together, as an immediate, practical response to “create a product”—an artwork, a theoretical frame, a praxis— “under our precarious circumstances: little budget, little time, and energy.” And this past July, shared intelligence was put to the test. Like a mirror of the societal paradigms it set out to critique, the students used the exhibition as form to subvert collectively improvised innovation for everything under the sun. To answer a question by Moulier Boutang, I’m not sure contemporary art was the agent at work, or if a new, emerging set of terms for artistic diversity and creativity demanded agency to critically experiment with the conditions of our networked society. Three years have passed at the Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art, and while the program will continue to hone itself at the edges of cognitive capitalism and neuroaesthetics, at its core is a genuine, open, global consideration of the rifts and approximations created by this developing and uncertain economy. With that heart, a new critical subjectivity can be tackled—a task for Neidich and future faculties to consider in sessions still to come.

—Jennifer Teets

Yann Moulier Boutang, Cognitive Capitalism (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011), 44.

Warren Neidich, The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism: Part Two (Berlin: Archive Books, 2014), 22.

See →.

Art Before Philosophy Not After is a work on paper by Warren Neidich that “challenges some of the initiating conditions of conceptual art in which art production performed a bridging condition between philosophy and art.” See →.

See →.