Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

March 25, 2021 – Review

“OTRXS MUNDXS”

Gaby Cepeda

The group show “OTRXS MUNDXS,” at Museo Tamayo, is a watershed moment: it’s the first standalone exhibition in the museum’s recent history to focus on young, local artists, all of whom work in Mexico City. Since the museum was founded in 1981, it has largely dedicated its spaces to promoting international artists and spearheading state-private alliances in the museum sector. That this inclusive, self-aware moment arrives in the throes of a pandemic, and likely out of institutional necessity rather than want, is unimportant. Is curating local—if only because of travel restrictions and vanishing state budgets—better than the usual fare of pre-packaged US exhibitions? It is to me.

It’s exciting to walk into a show full of familiar names and objects now comfortably nestling in the institutional bosom, which is why it is also disappointing that the conceptual bag into which these practices were thrown is so, well, generic. “OTRXS MUNDXS”—a non-binary spelling of the Spanish for “other worlds”—essentially attempts to other the work of 39 very different artists and artist groups and in doing so make the museum appear sympathetic to the zeitgeist. But there’s a contradiction in claiming these new practices as radical breaks with the past while …

June 11, 2019 – Review

Carsten Höller’s “Sunday”

Terence Trouillot

I was required to make a choice upon entering Rufino Tamayo’s famed museum in Chapultepec park in Mexico City. Wait up to an hour (or more) in line to crawl through Decision Tubes (2019), an interconnected web of mesh tunnels suspended in the sundrenched atrium that leads to different areas of the museum, or skip the wait and walk through Seven Sliding Doors (2014), a wall-to-wall mirrored hallway with automatic sliding doors that lead viewers into the main gallery space. These are the introductory artworks that open “Sunday,” Carsten Höller’s first survey in Latin America. Though the works in the exhibition all seem to promise a certain sense of amusement and playfulness, they are at best bewildering and surprisingly not fun.

This is not to say that Decision Tubes (myself and a group of friends finally decided to wait in line, begrudgingly) doesn’t spark a certain childlike glee, or at the very least a novelty experience, when awkwardly squirming through it. The work reminded me of a McDonald’s PlayPlace at every turn—a play area that most American children who grew up in the 1990s can remember with great fondness. But unlike its predecessor Decision Corridors (2015), a maze-like structure of …

February 14, 2019 – Review

“Nancy Spero: Paper Mirror”

Travis Diehl

Who was here first—Nancy Spero, or Hernán Cortés? It may be too much to call Spero (or anyone) a “universal” artist but her work certainly speaks to the weird postcolonial hybrids that survive as culture in the twenty-first century. Especially in this retrospective at the Museo Tamayo, a Brutalist building that shares a civic park and former world’s fair ground with Mexico City’s renowned Museo Nacional de Antropología, the scrolls, codices, and friezes that give form to Spero’s last four decades of printmaking—her Mediterranean references—make uneasy sense. In modern Mexico, layers of Spanish colonial, Aztec, and agrarian socialist civilizations build on the last’s rubble; for instance, a pre-contact, snake-shaped stone bowl fitted to a Mission era octagonal plinth becomes a font for holy water that is only superficially Catholic. Spero’s work, likewise, both matches and clashes perfectly with what’s already here. Thus the slight dissonance when you recognize in something like her series of figures dancing across long horizontal framed “scrolls,” such as Sheela and the Dildo Dancer (1987), the format of certain Mayan temple carvings. Whether this correspondence was the specific intent of guest curator Julie Ault and/or her Mexican hosts, or simply a kind of generic congruence of …

March 14, 2018 – Review

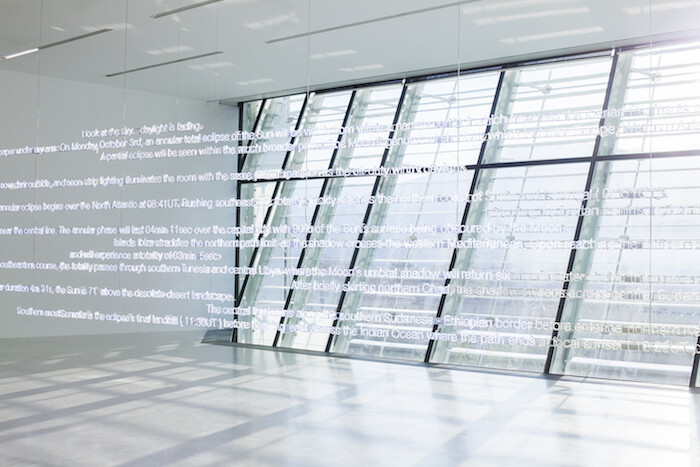

Cerith Wyn Evans

Chris Sharp

I’m not usually a fan of art about art, for the simple reason that it tends to perpetuate the potential solipsism of a perilously self-involved discipline, but something about Cerith Wyn Evans and his consistent ability to transmute art-historical references into quasi-mystical arcana has always struck me as agreeably mystifying. As such, I feel like he cogently, if urbanely, conveys one of the greatest secrets of art: that it is a secret. Or at least this is what I tell myself while walking around his first monographic exhibition in Mexico, as people rush around to take selfies in front of elaborate neon sculptures hanging from the ceiling. Virtually and refreshingly devoid of didactic wall labels, the exhibition both secretly and not-so-secretly (if you are an adept of the cult of Art) teems with references to some of the more recondite practitioners of art in the 20th century. I can’t help but wonder how the general public gains access to works that directly cite Marcel Duchamp or Marcel Broodthaers? The short answer to my rhetorical question is: they don’t. And maybe that’s okay. Maybe it’s enough to obscurely intuit that just beyond the mere appearance of a given thing lies a …