Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

January 21, 2016 – Review

Pat O’Neill’s “Let’s Make a Sandwich”

Leo Goldsmith

Los Angeles-based artist Pat O’Neill has been making work for the last 50 years, and yet it’s rarely seen in New York. A key figure in West Coast experimental cinema, O’Neill is probably best known for highly plastic and technically accomplished films like his lysergic 7362 (1967) or his extraordinary 35mm feature Water and Power (1989), an experimental documentary concerning, among many things, the development of the Los Angeles Basin from prehistory to the present. But since the start of his career O’Neill has also been involved in an astonishing range of media—photography, sculpture, collage, and installation, in both commercial and independent spheres. Now in his late seventies, O’Neill is the subject of his first New York solo exhibition, which offers a concise but judicious sampling of his varied output.

Comprising twenty-two works on paper, five sculptures, and three moving-image works, “Let’s Make a Sandwich” exhibits both O’Neill’s playful sense of humor and his fascination with diverse materials, images, textures, and technical processes. The visitor most familiar with O’Neill’s film work will recognize his sensibility in the other media immediately, as in the exhibition’s first object: the 2001 sculpture Forney Chair, a red wooden chair with a yellow lacquered cow horn …

May 18, 2012 – Review

Martha Rosler’s “Cuba, January 1981”

Scott Reger

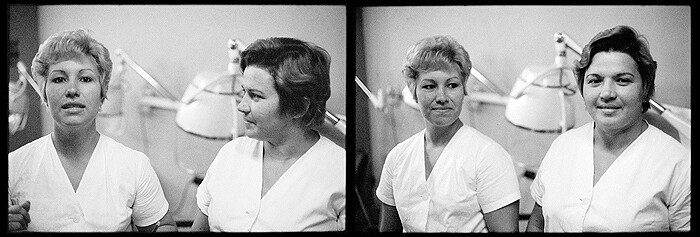

Hairdressers, Trinidad, one of several diptychs in Martha Rosler’s “Cuba, January, 1981,” shows two women looking at each other. In the first image, the blonde addresses the camera, seemingly in mid-speech, while the brunette watches her in profile. In the accompanying image, the brunette smiles for the camera, while the blonde looks on. The similarity of the two images, side by side, sets off clearly the line between looking and being looked at. This line has often been Rosler’s subject: capturing what is at work in the space between images. So a simple reconfiguration of the gaze between hairdressers delineates the spectrum of our assumptions—about power, photography, and, well, haircuts. We can see, suddenly, what it was we were thinking.

This operation is so effective it is often taken for granted. Rancière famously described a montage from Rosler’s House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967–72) as depicting “in the middle of a clear and spacious apartment, a Vietnamese man holding a dead child in his arms. The dead child was the intolerable reality concealed by comfortable American existence…”. Yet the man was actually a woman, the child was actually alive, and the “intolerable reality” had appeared in Life magazine, alongside, as …