Ho Tzu Nyen has long been preoccupied with the way history repeats in disguise: empire folds into empire, technologies of governance advance, and yet the conditions of control remain eerily familiar. In the Luxembourg iteration of the Singaporean artist and filmmaker’s mid-career retrospective, time is an instrument of power that measures mechanical precision against mythological recurrence: Ho’s work asks what it means to resist its rhythm.

Entering the exhibition, an arrangement of five screens laid out before woven mats suggests both an intimate gathering and a formal ritual. Collectively titled Hotel Aporia (2019), these video vignettes recount fragmented stories from Southeast Asian nations during the Japanese occupation, the faces of the characters deliberately blurred and anonymized by the artist. Hotel Aporia proposes that empire is not only about land but about temporality: to control time is to control narrative, labor, and even perception itself. Anonymity is not just an erasure but a symptom of the empire’s ability to reduce individual subjects to the status of interchangeable bodies, caught in the loops of time.

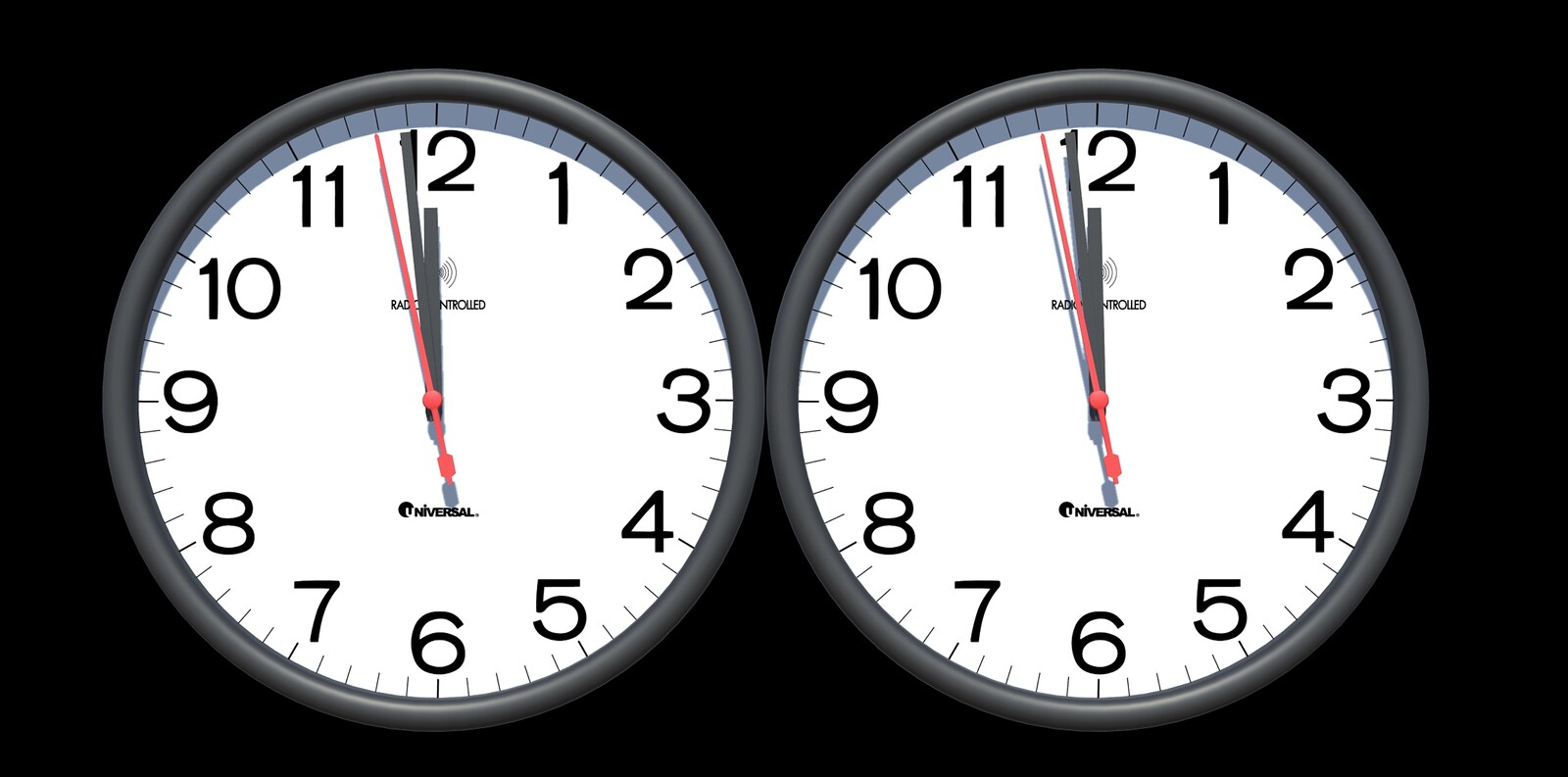

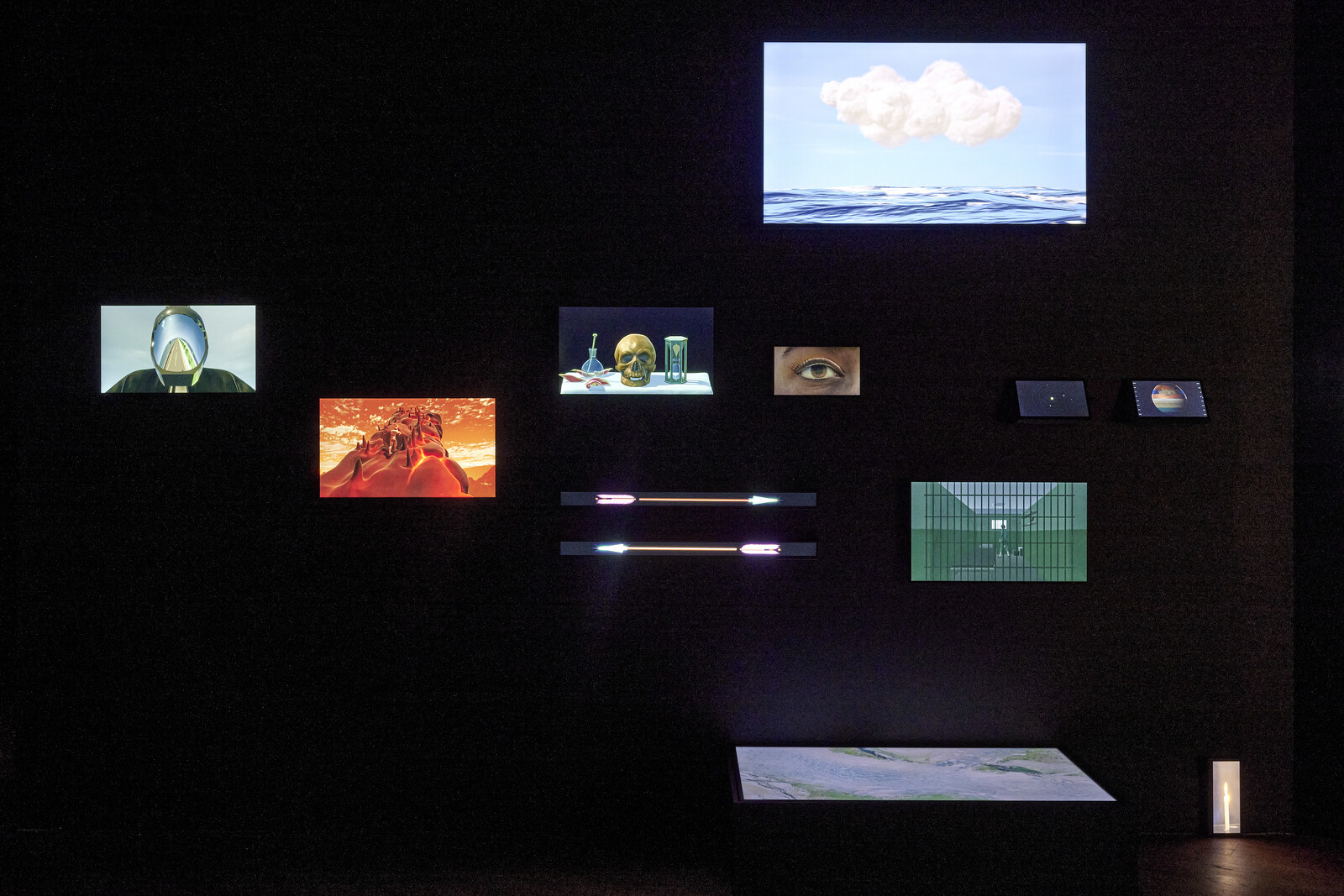

T for Time: Timepieces (2023–ongoing) gathers a constellation of luminous images—Sisyphus pushing his rock, a river flowing endlessly, a beating heart—on screens in a dark room, leading to the eponymous moving-image work. This algorithmically programmed montage mimics the way contemporary capitalism turns everything—even resistance—into circulation.1 Godzilla rips the clockface off Big Ben while a voiceover recounts the history of clock-time as an instrument of dominance. But the industrialization of time did not eliminate cyclical time; it merely converted it into a mechanical loop of production and consumption.

Ho’s work confronts the construction of identity through the lens of otherness. Nowhere is this more visible than in the west’s (resurgent) paranoia about communist infiltration, and in the racist ascription to the Asian body of such stereotypes as unknowability and duplicity. The absence from this iteration of the traveling show of key works including The Nameless and The Name (both 2015) and included at the Hessel Museum at Bard and the Singapore Art Museum) was, therefore, particularly keenly felt in this context. As long-standing European systems of capitalist and colonial time come under pressure—both from the left, in decolonial critiques, and from the right’s rejection of globalization and embrace of disinformation—Ho’s exploration of shifting allegiance, interchangeable identities, and historical recurrence through the figure of Lai Teck, secretary-general of the Malayan Communist Party from 1939 to 1947, feels especially pertinent.

Fortunately, the fascinating story of this notorious triple agent is presented in The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia (2017–ongoing), an ever-expanding, algorithmically generated archive of images, texts, and sounds. The spy, like the tiger a recurring figure in Ho’s work, is a counterpoint to the sovereign: both are interchangeable, yet while one consolidates power, the other disrupts it. Espionage operates in cycles—figures disappearing and reappearing in different guises, shifting between allegiances, embedded within the machinery they seek to unmake.

Yuk Hui has argued that the imposition of universal time effectively eradicated local temporalities, replacing pluralistic understandings of time with a single globalized structure.2 Based on a nineteenth-century lithograph, One or Several Tigers (2017) stages an encounter between British colonial surveyors and a tiger in the forests of Singapore. The tiger is both a rupture in the imperial logic of time and an anchoring figure for the slave laborers whose lives were sacrificed in its service. This relationship between extraction and surveillance is underscored by the surveying instrument, which transforms land into property, subjects into data.

The act takes on a mythological dimension: as British incursions reduced tiger populations, legends of weretigers—humans who transform into tigers—proliferated, blurring the line between the colonized body and the spectral threat to empire. Following the logic of Johannes Fabian’s Time and the Other (1983), which demonstrates how colonialism excludes other cultures from the concept of time, placing them “outside” history, the work frames the tiger as a subject that resists synchronization and an agent disrupting historical narratives. The tiger, like the spy, is a glitch in the imperial clock recurring in different forms through the exhibition, slipping between past and present, resisting classification, evading capture.

As European colonialism required surveillance, discipline, and synchronization, so contemporary forms of empire have refined its mechanisms. Ho’s tigers, spies, and ghosts speak to a present in which identities are monitored, rendered interchangeable, and instrumentalized by algorithmic systems that promise efficiency while deepening asymmetries of power. The weretiger finds new analogs in digital infrastructures that render subjects hypervisible yet unknowable, classified yet never fully seen. The spy has evolved into the bot in a world shaped by data extraction.

To control time is to dictate whose histories are remembered, whose bodies are visible, whose power is enshrined. Yet time, in Ho’s work, does not belong to empire alone. It is contested, inhabited by figures who refuse to be fixed in place, are not constrained by its patterns. The spy remains, shifting identities. The tiger continues to prowl the edges of empire. The past never fully settles. We are left not with a singular truth but with a chain of echoes, each iteration slightly different from the last.

Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism (2009) argues that postmodern culture no longer produces new temporalities but instead endlessly recycles the past. Ho’s algorithm reflects this condition: each new iteration is different yet fundamentally the same, a “zombie time” in which events occur, but nothing changes.

See Yuk Hui, The Question Concerning Technology in China: An Essay in Cosmotechnics (London: Urbanomic, 2016).