A storm is raging in Singapore. Waves break against park benches and dash against trees. Public housing estates are half-submerged; bobbing on the water surface are abandoned lifeboats and jackets. With Disaster-free (2024), featuring footage generated with the help of AI, artist Ong Kian Peng has created a Singaporean disaster movie, in which rising sea levels have transformed the developed island-state into a gray, glimmering water world that we scan through the eyes of a single survivor paddling around in a kayak. Amid an unseasonally late monsoon season in January, I found this end-of-days scenario a calming respite in this year’s frenetic, more-is-more, soft-power flex of a Singapore Art Week (SAW). The institution, in its thirteenth edition and styled as “Southeast Asia’s pinnacle visual arts event,” packed more than 130 events into a ten-day run in venues across the island, including galleries, units in several dingy malls, and a miniature gallery with tiny artworks strapped onto the back of a roving artist.

Anchoring SAW are two art fairs: the flagship ART SG, in its third and smallest edition with 105 galleries at the Marina Bay Sands, and the smaller S.E.A Focus fair, showing Southeast Asian art in a boothless, free-flowing show at Tanjong Pagar Distripark. Beyond these are a variety of events shading into academia, lifestyle, retail, fashion and even hospitality: scholarly symposia, concerts, “canvas to cuisine” food tastings, and a Louis Vuitton x Murakami pop-up—the offerings so diverse that I wondered if this could be a manifestation of late-stage Art Week-ism, where an apparent appetite for novelty, relevance, and buzz make the curation ever more cross-disciplinary and capitalistic.

Although there is no theme, the event does provide a snapshot of the arts ecology of Singapore and its preoccupations. The most salient point is that most of the party is paid for and orchestrated by the state, which comes with attendant pros and cons. Government pockets are deep and generally support a wide array of practices, from investigative, process-based works to other genres consistent with nation-building goals, like tech-and-art hybrids (in tandem with Singapore’s larger plan to be a “Smart Nation”) and wholesome community-based interventions. If the overall goal of the arts council is to showcase the dynamism and vitality of the local arts scene to residents and visitors, then there remain no-go areas, such as showing works openly critical of government policies.

In this charm offensive, public institutions lead the charge by spotlighting practices of regional contemporary artists. At Singapore Art Museum, there are solo exhibitions of Pratchaya Phinthong and Yee I-Lann, as well as the return of Robert Zhao Renhui’s Singapore Pavilion from the most recent Venice Biennale; the National Gallery Singapore features conscientious career retrospectives of local stalwarts Kim Lim, Teo Eng Seng, and Lim Tzu Peng. The newly minted Tanoto Art Foundation, founded by the billionaire Indonesian family of the same surname and “dedicated to nurturing dialogues around the experience of contemporary art in Southeast Asia,” opened with a symposium: Joan Kee’s keynote lecture explored the history of South-South exchange in art with reference to diasporic artists and art events in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Virtual reality and game works were plentiful. The exhibition “Affective Architecture,” held at Black Box on 42 Waterloo Street, was devoted to virtual worlds, especially Asian-futuristic ones that blend historical and technological elements. With a keyboard, I cruised the strange watery realms of Sahej Rahal’s Azalabad (2023) and passed under colossal architectural ruins that recalled the shapes of human faces and spidery monsters. At the NTU Museum’s exhibition “Construction at Every Corner,” I strapped on a VR headset and nosed around the high grasses in Debbie Ding’s portrayal of Singapore’s vacant plots of land awaiting redevelopment (wastelands, 2024).

Another thematic thread in SAW was the excavation of Singapore’s regional histories. “The Eye and the Tiger”, which took the form of a guided tour in and around a black-and-white bungalow in Adam Park, explored the colonial legacy in Southeast Asia of racialized policies and resource extraction. Highlights included Maryanto’s charcoal drawings of the sand-mining operations around Mount Merapi, an active volcano, in Indonesia. These vertical canvases, suspended from the ceiling, depict a cross-section of the earth, so that our view is dominated by a wall of soil and rock that has been violently gouged and exposed. Exploring a different kind of violence is Chong Kim Chiew’s installation Isolation House (2005), which references the “New Villages” set up by the British to house Malayan Chinese suspected of supporting communism from 1948 to 1960. Inspired by these glorified internment camps surrounded by barbed wire, watchtowers, and armed guards, Chong created a cage-like installation that starts indoors and extends outdoors into a cage in the sun, viscerally evoking the dehumanizing experience of refugee camps, detention centers, and prisons.

All the historical soul-searching would be moot if there were no reckoning with the present. Depending on where you look, art can be considered an exceptional or unexceptional space to the city-state’s draconian rules against dissent and its prohibitive attitudes to LGBTQ+ communities. An unhappy example would be the R21 rating slapped on Charmaine Poh’s videowork What’s softest in the world rushes and runs over what’s hardest in the world (2024), which platforms queer families in Singapore.1 At Sundaram Tagore gallery, the work was represented by a gray wall in protest at the restriction, and the video shown only in a private screening.

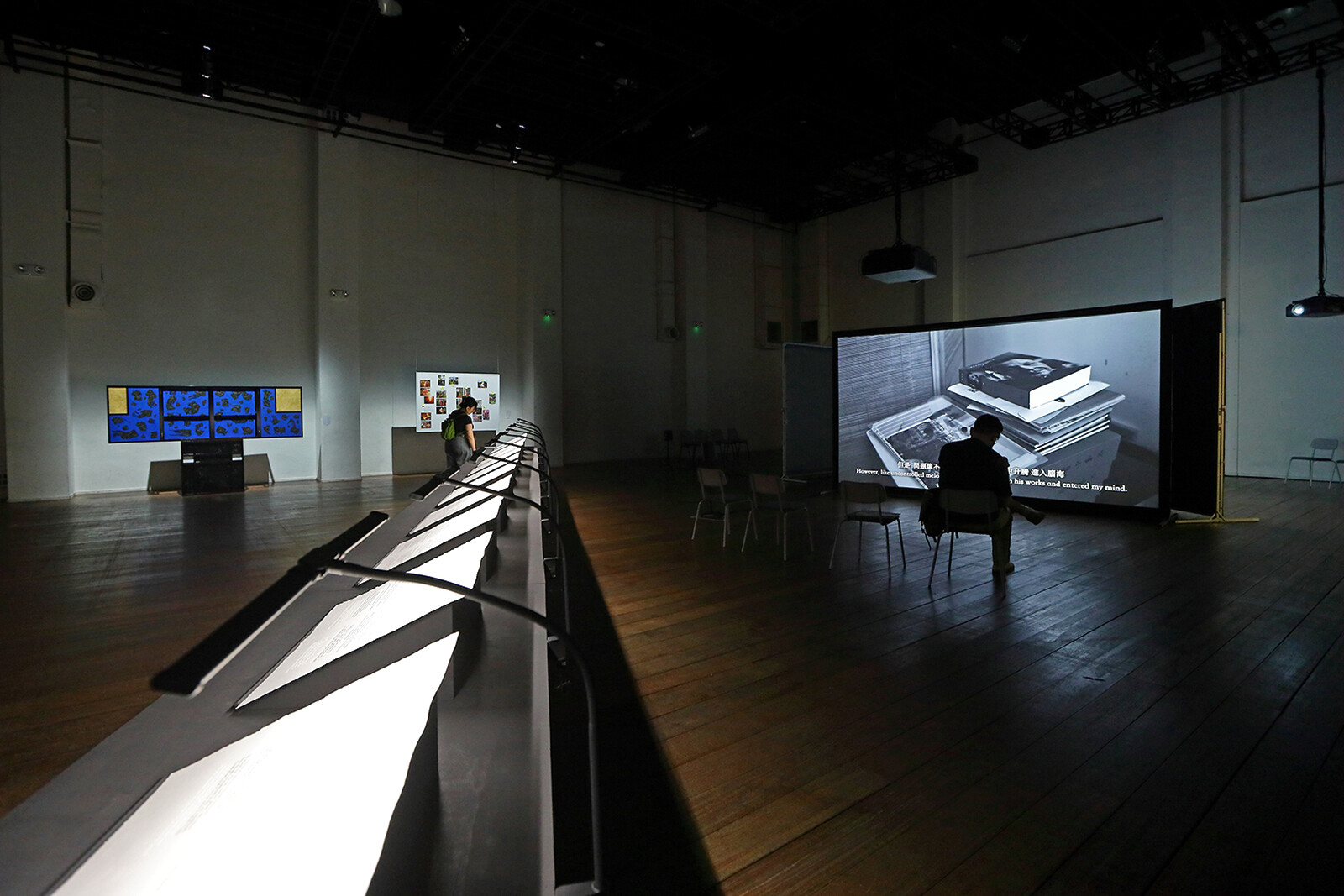

The exhibition “Utopia of Rules” has a more nuanced take on the issue, exploring how art opens up a space for subtle negotiations of rules and regulations. Heman Chong photographs the backdoors of embassies around the world, drawing attention to the lines at which two sovereign entities end, as well as the idea of slippage between territorial realms (Foreign Affairs #1, 2018). Charles Lim’s alpha 3.9: Silent Clap of the Status Quo (2016) shows underwater footage of a deep-sea communications cable laid around Singapore, obtained from a company that installed those fiber optics and filmed the entire length of it as evidence of work completed. While the work’s subject is the physical infrastructures that underpin the digital world, it is also an instance of how an arcane, almost forensic document can be recontextualized to create new affects: the way the camera crawls over this subterranean and seemingly endless cable on the seabed is akin to the slow reveal of a monster’s body in a horror film.

Lest we wax too optimistic about art’s potential for subversion, some updates on the current political climate. In the past few months, the Singapore government has issued several POFMAs (orders deriving from the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, passed by the government in 2019, ostensibly to protect the public from fake news but being deployed at the authorities’ discretion) to several news agencies and an anti-death penalty activist group. Some works captured a mood of high-functioning depression in ambient stress. Joaen’s Overwhelmed - Coping (2020) is a batik drawing of a naked woman, executed in squiggly frantic lines, being squeezed by cartoon arrows pointing inwards to her body, and force fed through a hose.

Also part of SAW is the Light to Night festival, during which the city’s buildings are prettily illuminated against the darkness. In that context, Ang Song-Ming’s confessional text works, projected word-by-word onto Victoria Theatre and Victoria Concert Hall to the accompaniment of a jumpy, dissonant noise soundtrack composed by the artist, constituted a giant middle finger to the corporate-statist world. “This artwork will not sing for you.” “Quit your weasel words. Quit your crocodile tears. Quit your lapses in judgement. Quit your thoughts and prayers. Quit your greenwashing. Quit your sport-washing. Quit your culture-washing.” Sometimes it’s just a howl of despair: one text work comprised the word “NO” repeated over and over in different font sizes. Amidst the celebratory mood of SAW, this was a bracing scream of anguish and defiance that, to the event’s credit, was not quite silenced.

The R21 rating restricts viewing of the work to those over the age of 21.