One month after the second part of “Ecologies of Peace” opened in Cordoba, much of Spain was underwater. On October 29, more than an average year’s rain fell along the country’s southern and eastern coasts, killing over 200 people. Days later, crowds in Valencia pelted King Felipe VI and Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez with mud, blaming them for the state’s lack of emergency preparedness. The worst natural disaster in a generation became a political crisis.

If the ruling classes continue to prove themselves unwilling to address the climate emergency, then it’s fair to say that artists aren’t going to save the world either. But this show at C3A proceeds from the limited if hopeful assumption that they might be able to make a difference. Half of a group exhibition in two acts, “Ecologies of Peace” emerged from a series of partnerships between TBA21 and underfunded regional institutions, and at first glance, its title shares a sunny vagueness familiar from biennials in other parts of the world. Curated by Daniela Zyman, it claims to focus on “practices of mourning and forgiveness,” though, for the most part, it illustrates the scale of the devastation that calls for them.

“One has to learn how to be critical of everything, even the conceptual apparatus that one uses to generate understandings,” Angela Davis says at the outset of A World of Greater Freedom (2023), Manthia Diawara’s documentary portrait of the activist and scholar in which she argues that racism must be understood in relation to patriarchy, homophobia, and class exploitation. Indeed, the “ecology” of the show’s title invokes precisely this sense of interdependency, though “peace” is hardly anywhere to be found.

Instead, many works in the exhibition focus their lens on specific cases of violence, from colonial apartheid to industrial extraction. The photographs in Allan Sekula’s Black Tide/Marea Negra (2002–03) document the aftermath of a crude oil spill from a tanker off the coast of Galicia, which devastated the Spanish fishing industry. Against the white Tyvek suits of the cleanup crew, black crude sludge stands out in ominously stark relief. Commissioned by the Catalan newspaper La Vanguardia, the project included an opera libretto whose final act of resistance to petrocapital, “The Song of Society Against the State,” suggests the degree of environmental activism needed to prevent such disasters from happening again.

In an adjacent gallery, Mirna Bamieh’s installation Bitter Things: The Kitchen (2024) takes a more expansive approach to the effects of colonialism and ecocide on the food supply. Round, brightly colored kitchen furniture is overladen with jars of hand-squeezed juices and marmalades, all made from bitter oranges. Once the most famous export of the Palestinian port town of Jaffa, since absorbed into Tel Aviv, the oranges are one of several foodstuffs whose production is tightly controlled by the state of Israel, and many are grown in groves confiscated from Palestinian farmers during the Nakba. An accompanying video meditates on the ways that memories—of taste, smell, and family traditions—don’t obey borders. An act of resistance can be as unassuming as a bite from a fruit.

Several works consider the toxic impacts of war on the individual and social body. A vitrine holds fifteen glass slides etched with the flight plans of Israeli jets that invaded Lebanese air space between 2007 and ’22. Lawrence Abu Hamdan collected the data on his website AirPressure.info; placed one atop the other, their incursions appear so dense and frequent that the recognizable form of Lebanon comes to resemble a black lung. Abu Hamdan calls the work a “sonic image,” and its ghostly effect invokes the psychological trauma inflicted by the jets’ sonic booms. Similarly, Cristina Lucas’s “Tufting” (2017–ongoing) features maps of various regions around the world embroidered with the names of sites where civilians have been killed in conflict. Palestine and Lebanon are so thickly threaded that no white linen peeks through their coal-dark surface.

Walid Raad and the Atlas Group applied a similar mapping technique to an archive of photographs taken during the Lebanese Civil War. Colorful dots affixed to burnt and blasted landscapes locate and classify bullet holes according to the size and original manufacturer of their shells, proof that local and national conflicts are often subject to geopolitical intrigue. A slow-motion video by The Propeller Group, meanwhile, shows different kinds of bullets piercing a block of translucent ballistics gel, its rippling putty the same density as human flesh. Both works are unassuming at a glance, and visceral once you recognize their violent conceits. The same is true of Fiona Banner’s Parade (2004), which hovers cheerfully above the same gallery. A toy squadron of all 201 fighter planes in use around the world feels at once juvenile and sinister, casting dark shadows against the museum’s walls like birds of prey.

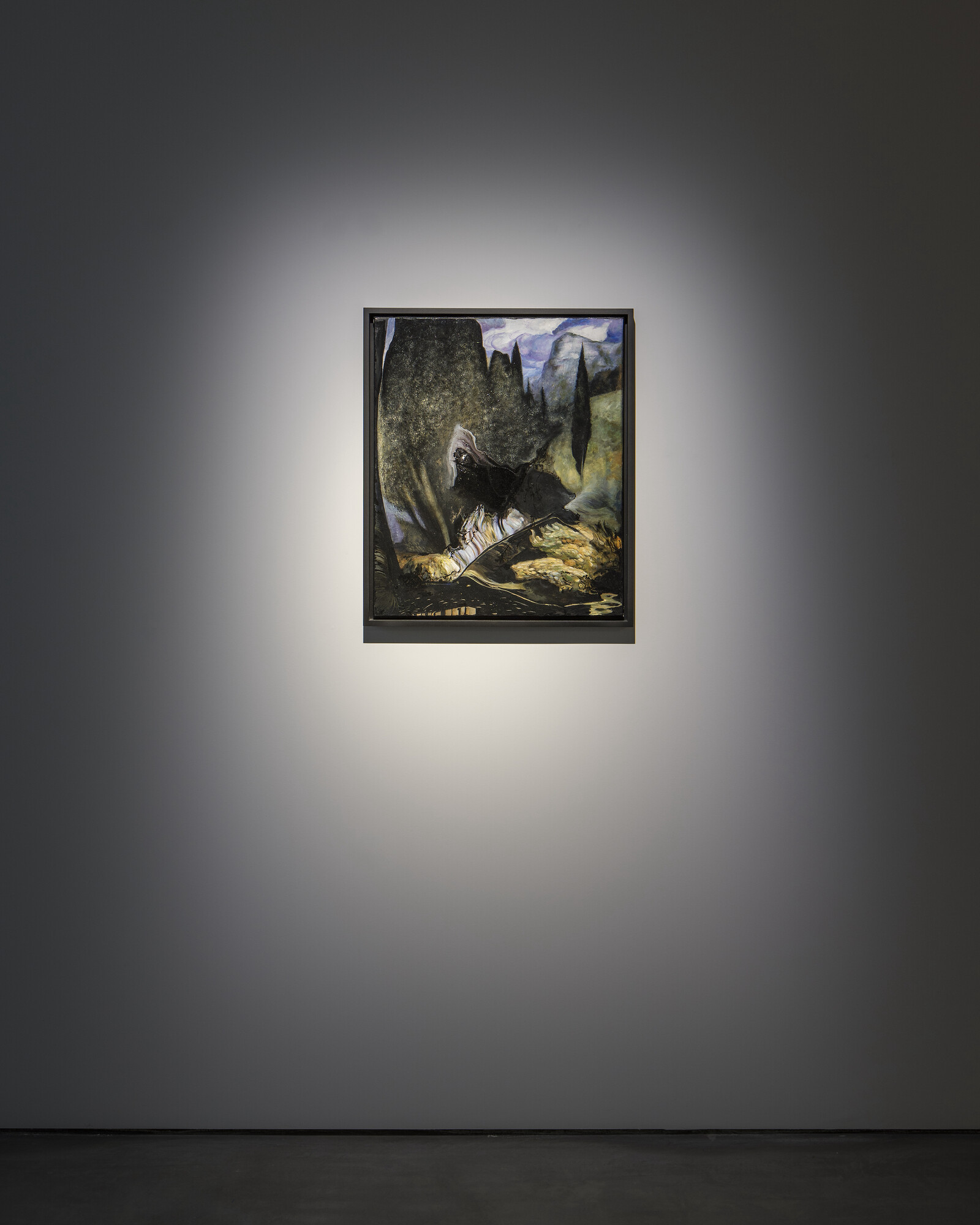

C3A’s stygian architecture—with a honeycomb floorplan in unfinished concrete, part bunker and part beehive—is generally well suited to the exhibition’s themes. Yet certain works can seem overly literal in this context, from Banner’s warplanes to Ryan Gander’s marble resin replica of an ancient Gaul statue, recast here as a legless amputee. Allora and Calzadilla’s ham-fisted Petrified Petrol Pump (2010) is a fossil for a future without fossil fuels. Other inclusions are, by contrast, too subtle: works by Lucas Arruda, Rachel Rose, Vivian Suter, and Álvaro Urbano are aesthetically pleasing but, apart from their depiction of plants and use of organic matter, don’t do much to develop the theme.

Taken as a whole, however, the show proves that by visualizing data, field research, and witness testimony, artists can contribute significantly to our understanding of polycrisis. These days, less is known about the ecology of peace than of war. This may be the exhibition’s most salient point: before rebuilding, it is first necessary to gather the dead.