Meditations on the nature of temporality abound in Ho Tzu Nyen’s latest video work, T for Time (2023–). We have explainers on timekeeping traditions in the East and West; a vignette about a man who maintains Singapore’s oldest public clock; the origins of Greenwich Mean Time; metaphysical musings on non-linear time (“time conceived as a viscous fluid… it does not pass and has no rim… it pools”). Accompanying most of these are digital animations that sometimes illustrate the concepts—like imagery of a molting ouroboros—and visuals with less obvious connections to the theme, such as recurring scenes of political protest and incarceration. Most of the text is sung by a male narrator in seemingly improvised melodies. Content, which is shuffled by an algorithm, starts to repeat only about seventy-five edifying minutes in. I was intrigued, stimulated and entertained, but couldn’t escape the feeling of being lectured to. This has something to do with the video’s heavy reliance on text: this work narrates itself.

Ho’s self-narrating, self-theorizing, and sometimes even self-interpreting practice involves a thorough immersion in a range of research topics, resulting in a cathartic showing and telling that has become his signature style. “Time & the Tiger”, a mid-career survey of works made from 2003 to the present day offering a cogent genealogy of Ho’s practice, focuses on questions about identity and history, most notably “What is Southeast Asia?” and “What is Singapore?” Six of the eight works on show are long-form videos, and the show is probably best digested in several sessions rather than in one go. The video works utilize a range of sexy cinematic techniques, including 3D scanning, motion capture, and algorithmic editing systems—which highlight the artist’s canny manipulation of futuristic technological tools to explore questions of the past. In his video works, I am as often impressed by the intellectual curiosity of Ho’s work as by the surprising use of imaging tools to generate disconcerting atmospheres that disrupt our habitual perceptions.

The show’s starting point is Ho’s unified field theory of a work, CDOSEA (short for The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia, 2012–), a video work which fleshes out the commonalities in a region that “has never been bound by a single religion, language or political system.” From his research on Southeast Asian histories and cosmologies, Ho has created an A-Z glossary of terms (e.g. C for Circle/Corruption, M for Mandala, P for Padi (rice)/Politics/Plateau), which are then sung out by vocalists. Accompanying the text is footage scoured from the internet that is tagged and shuffled, so that each viewing of the video is different. Just as there’s a certain type of sweeping and morally serious fictional work that’s shorthand for the Great American Novel, CDOSEA could arguably be described as the Great Southeast Asian Artwork, as it creates a pulsing, polyphonic and protean archive of regional representations that came together and fall apart in an unfolding process of legibility and obscurity, becoming and unbecoming. But I’m not so sure about its presentation here. I often access this work from its website, and enjoy the scrappiness and blatant piracy of the found footage.1 Seeing it cast on a large screen, intermittently blasted by flashes of white light that mark the transition between scenes, gave it a sense of majestic officialdom and monumentality that feels at odds with its content.

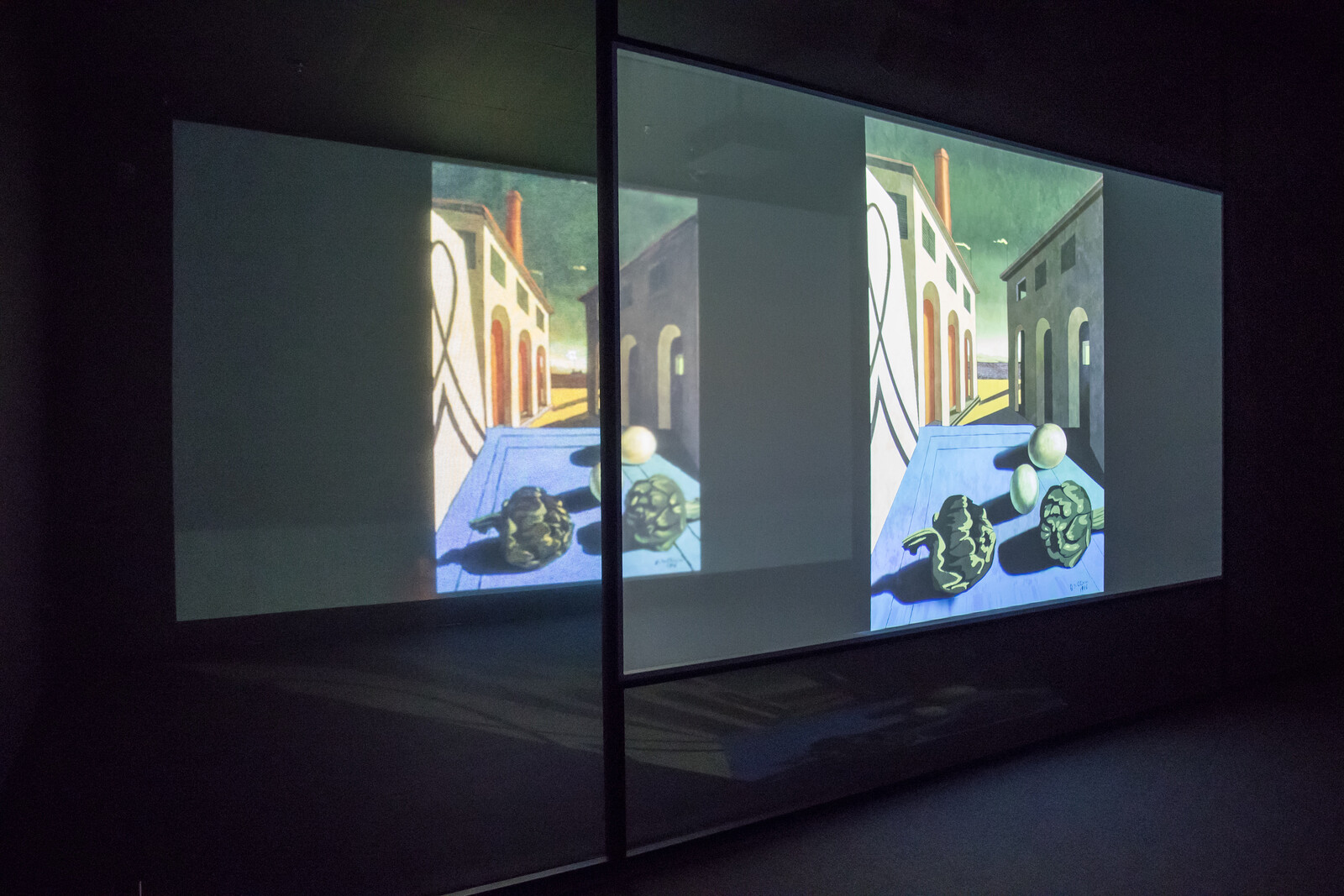

Following that, the exhibition branches off into letter-specific spin-offs. The video installation One or Several Tigers (2017) is based on the concepts explored in the letters T for “Tiger/Theodolite,” and “W for Weretiger.” The two-channel work is inspired by two figures in German lithographer Heinrich Leutemann’s print Interrupted Road Surveying in Singapore (c. 1865), in which a tiger pounces out of the jungle during a surveying expedition and breaks a theodolite, an instrument that measures angles horizontally and vertically. The viewer stands between two screens, one depicting a Malayan tiger and the other showing a behatted and besuited surveyor George Drumgoole Coleman, who worked for the British colonial administration in Singapore. Both characters are rendered in hi-def 2D animation, so that every whisker and pore can be seen in uncanny detail. In high and wobbly sing-song voices, they perform a duet which sets up various binaries: Indigeneity/colonialism, magic/rationality, more-than-human/human. Sample lyric from the tiger: “In a human there live two animals that never coincide. The first is made of words, and the second is made of flesh… We’re tigers. Weretigers.”

Despite them being foils, things never get predictable or schematic because of the extravagant strangeness of the work; it is as if we are witnessing a dialog between gods in a language we barely understand. The tiger is magnificent here. Tigers hold a special place in Ho’s work, because they were once prevalent in Southeast Asian jungles and Indigenous folklore, but their numbers dwindled when the region came under colonial rule. Over the years, Ho has developed several tiger-related works where the animal is a charismatic and shapeshifting force—and here it achieves the apex of reality-scrambling weirdness, standing up on its hind legs with a permanently raised paw, singing in a strangled, mournful voice while morphing into a human and finally, a sun.

While “Time & the Tiger” shows the generative model of Ho’s thinking, the show also includes some standalone projects that look at Southeast Asia from the outside—this time, from the Japanese perspective. Hotel Aporia (2019), a six-channel video which features several Japanese figures who have lived through World War II, engages the intellect, emotions, and the body. The viewer sits on tatami-covered floors to watch the video screens (each contained within a traditional Japanese house); one focuses on the kamikaze pilots and their final gatherings before their suicide missions, while another revolves around Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu’s short time in Singapore to make a propaganda film for the Japanese Imperial Army, which did not materialize. Clips from Ozu’s films are included, but with the faces of the actors replaced by blank, grey ovals. Another video explores the philosophies of the Kyoto School, which fused Zen concepts of nothingness with Western ideas of being. Some of these philosophers were notoriously pro-war nationalists.

As its title suggests, Hotel Aporia depicts a state of internal contradiction. The greatest tension in the work comes from the abstract philosophical elegance of Kyoto School, set against the material sacrifices of the kamikaze soldiers (from pilot Sakae Miyauchi’s letter to his parents: “Up to now I drank a little alcohol, and I did not know a woman at all”). The incongruities come to a head in the last house, which features the Kyoto School’s most famous philosopher, Nishitani Keiji, discussing the subject of the wind in the work of Haiku poet Matsuo Bashō. Bashō used the metaphor of being like the wind to denote a sort of madness, which he calls “non-settlement;” but in drifting, he argues, “there is a thread,” which is “the artistic and creative life.” How on earth could such tender philosophy, or the friends of such philosophy, be weaponized? And the generals definitely thought the gods were on their side: kamikaze means “divine wind,” named after the legendary storms that twice saved Japan from Kublai Khan’s Mongol fleets in the thirteenth century.

There is no video screen in this house, only the Japanese audio and English subtitles running on a narrow strip close to the ground. In lieu of a monitor, we face an industrial drum blower fan on full blast. The minimalist set-up of the room allowed the sounds and images from the other houses to haunt this space—the faceless characters in the Ozu clips, the songs of the kamikaze soldiers, the recollections of their final moments—so that the round face of the fan took on the quality of a detached, powerful witness, piping out a cool, endless breeze.

The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia, https://cdosea.org