Sometimes an artwork responds to the world outside; sometimes the world outside responds to an artwork; and sometimes neither knows of the other, yet each is enhanced by it all the same. Such a moment occurred recently when one could march down Piccadilly, in protest with and in the presence of tens of thousands of women, and turn into a side street, past cars, jammed, Porsches, Bentleys, and Rolls, in each a man tapping agitated fingers upon a leather steering wheel, enter the glass door of a gallery and there find a mannequin, female, with long crimped hair and army fatigues, an assault rifle at rest by her side.

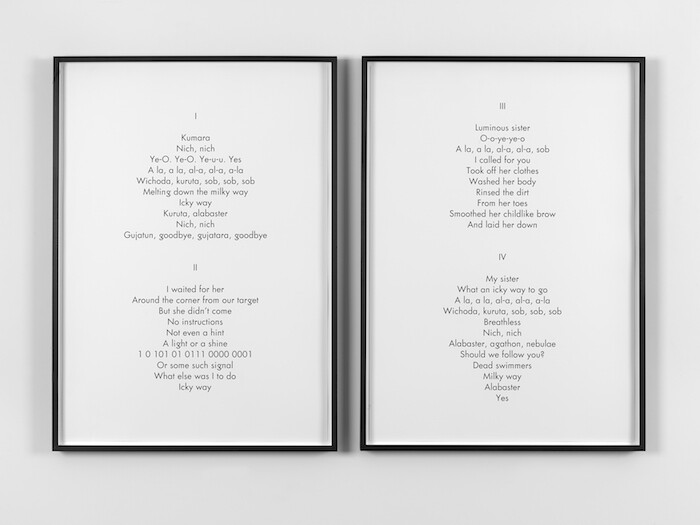

The work is by the Swiss artist Mai-Thu Perret, and takes its name—Les guérillères XII (all works 2016)—from the influential (one can scarcely say “seminal”) 1969 novel by Monique Wittig, which imagines a new society established and run by lesbian warriors. In the original French, they are described as “elles,” not “women” but a differently universal “they,” a simple inversion of the masculine collective pronoun “ils” one usually finds in French; Perret’s own narrative of a female commune, The Crystal Frontier, which she has been writing—and making artwork from—since the late 1990s, might be considered a similarly speculative reversal and, like Wittig’s own work, is not based upon any sense of gender essentialism.

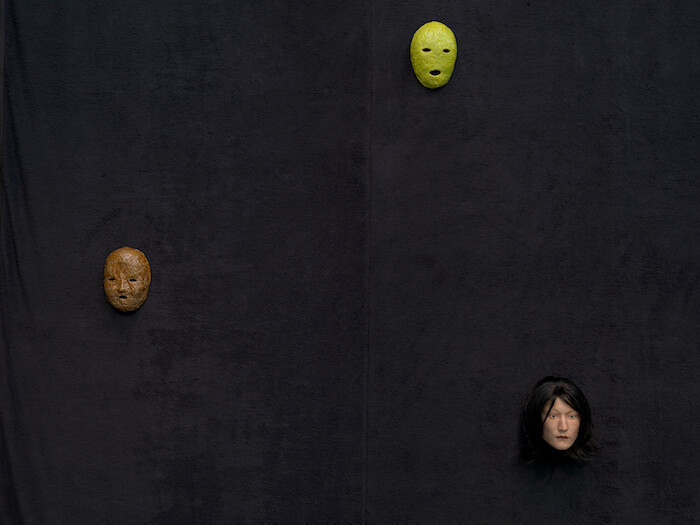

But the warrior is made of papier mâché, her gun is cast in resin, and, like much of Perret’s work, sits at a point between action and reflection, engagement and withdrawal. Many of the avant-garde movements of the earlier twentieth century might now be considered to occupy a similar place, where political materialism advanced alongside aesthetic abstractionism, and in so doing they have become an important source for much of Perret’s work. In this exhibition it is Sophie Tauber-Arp’s “Dada Heads,” turned wooden forms resembling hat stands, and often similarly featureless. In Perret’s Natural Sophie, the scale has been increased markedly, the height of this “head” now the height of our entire body, and its material altered, now woven in wicker and so referring back to the applied arts within which Tauber-Arp was first trained, and also the craft objects which the members of Perret’s fictional commune might occasionally sell at local markets. If its scale gives it immediate presence, the blankness of its form gives it distance, too, something which Perret has previously spoken of as being important to make abstract her own subjectivity. No doubt this also relates to the various “faces” or masks within Figures II, two of which are ceramic and simply formed, almost as though pareidolic finds, and one of which is made of silicone and far more realistic, even if it then comes to settle within the uncanny valley.

This sometimes fraught relationship between art and craft is explored within many of Perret’s works, not least in the different ways in which they have been, and continue to be, gendered. (We should remember that many radical female artists, such as Tauber-Arp, or Anni Albers, were not allowed to study the subjects that they had hoped, but were diverted into the more acceptably female activities of weaving and textiles.) In our age of mass production, a premium is placed upon the handmade, financial usually, but also to some extent ethical, that an object made through unalienated labor is more worthy, worth more, than that made within a more usual factory process. Given that most craft objects suggest utility even if they are never used for their particular purpose, perhaps we must think less about the production of the object as a form than of the production of a form of society which allows the object to be brought about, or made desirable.

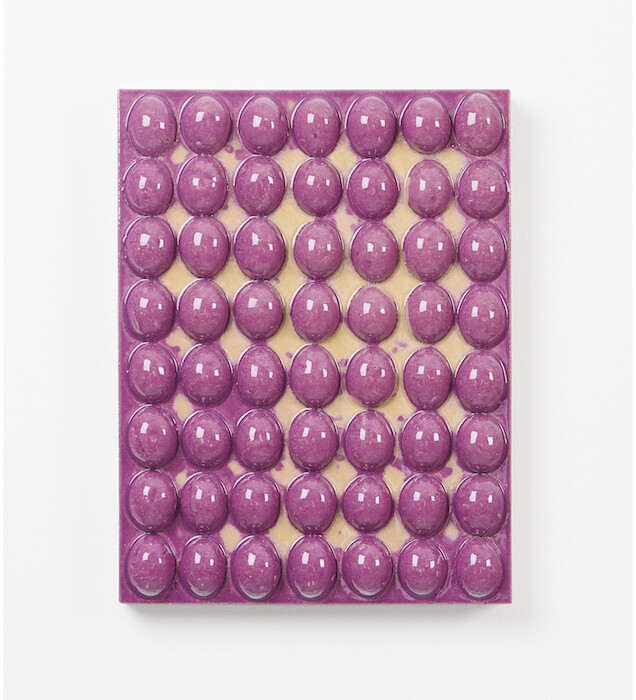

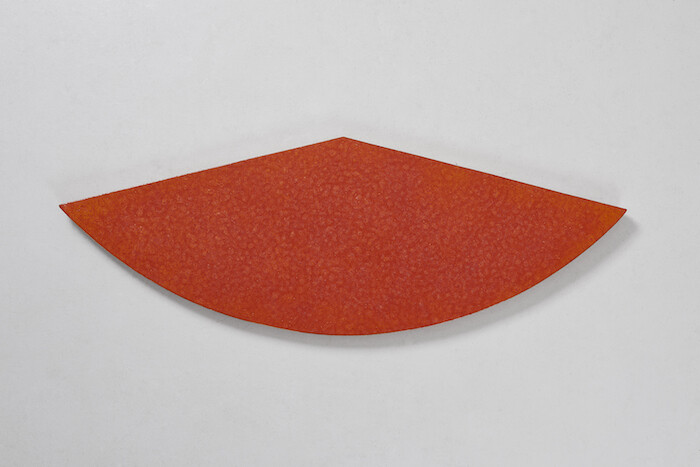

This becomes all the more complex when such objects are considered to have been made from within Perret’s imagined society as they enact another, different, form of masquerade. Here, the handmade is not only made by hands other than those suggested, but the resultant object is, what? An art object masquerading as a craft object, or a craft object masquerading as an art object? Perhaps one needn’t settle upon an answer. The wall-mounted ceramic works here—tiles in two colors in various arrangements; rows of egg forms, as if placed within a box-tray; a tablet like a lustrous bruise clenched at its edges—all take as their titles capping phrases used within koan meditation. Once a monk has replied to a koan with satisfaction, the Zen master instructs the monk to find a fragment from a classical verse, or within a specially compiled phrase book, that expresses the newfound insight. Inevitably, these found texts are as open as those which prompted them, and here, used as titles, they suggest a way into the work which also leads elsewhere, to an experience which is precise, elusive, beautiful, open, endless.