David Noonan and Renee So, whose work is shown in concurrent solo exhibitions at Sydney’s Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, share an interest in the research, appropriation, and reconfiguration of traditional iconography. Hung on the walls of the main gallery, hidden down a terraced street in the suburb of Paddington, David Noonan’s “Lead Light” consists of twelve silk-screened collages on linen (all works untitled, 2016), their monochrome tones drawn out by the charcoal sisal carpet with which the artist has covered the walnut flooring of the gallery.

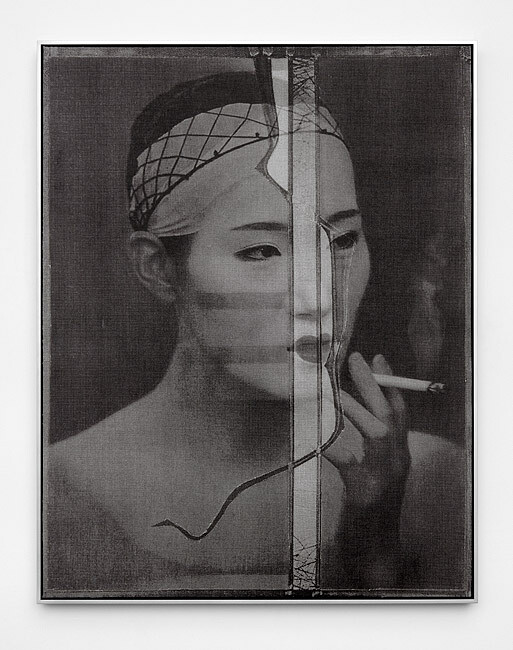

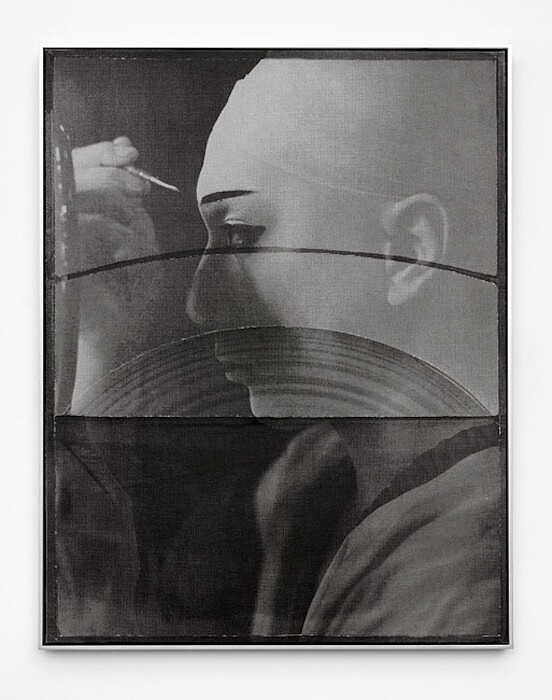

Noonan’s theatrical, enigmatic pieces are composed of layered photographic portraits of performers applying makeup. They are overwritten with abstract designs derived from leadlights, decorative windows made of cut sections of glass joined by lead strips. These superimposed images meld tempos, traditions, and styles, blurring arts and crafts, painting and photography, abstraction and figuration, breaking down hierarchies of subject and style. By interweaving figuration and abstraction, creating obscure and strange atmospheres, they bring to mind Man Ray’s mysterious photographs—Barbette Making up (1926), for instance, in which the face of a vaudeville performer applying makeup is reflected in two mirrors—as well as Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus costumes.

One of the most intriguing works is a portrait of an actor who stares directly at the viewer. He wears Kabuki makeup, the stylized forms and colors of which are used to communicate the personality of the character. His face is coated in white foundation, and darker geometrical lines convey a calm but strong nature. Noonan has juxtaposed three rectangular surfaces on the picture of the persona—a term that in its Greek origin also referred to the role denoted by a theatrical mask. These overlays create an uncanny window-like fragmentation that evokes the different strata of which every individual’s personality is formed. An attractive but distant woman wears makeup and an attitude indicating that she is a Geisha. Hidden behind translucent veils of linen, she is inscrutable. Noonan’s overlaying of various screens results in simple but sophisticated collages, all impenetrable and emotionally charged.

Renee So’s exhibition “Vessel Man,” in a smaller adjacent room, comprises six portraits of strange characters with playful and humorous overtones. Drawing upon traditions of theater costume, Assyrian sculpture, ancient pottery, and cartoon graphics, So’s work can be seen, like Noonan’s, as amalgamations of styles and histories. Her ceramic vessels—displayed together on a single pedestal at the entrance of the room (all titled Bellarmine, 2016)—are inspired by the Bartmann or Bellarmine beer jugs manufactured in Germany and popular across Europe in the sixteenth century. Decorated with a bearded face-mask descended from the mythical medieval figure of the “wild man,” the jugs are reinterpreted by So as totemic sculptures. Bellarmine XIII (2016) is a figurine that recalls both ancient Chinese cauldrons and Mesoamerican tripod vessels. The face of this anthropomorphic figure is formed by two headed figures joined by a vine beard. The object casts itself as a symbol of merged lineages.

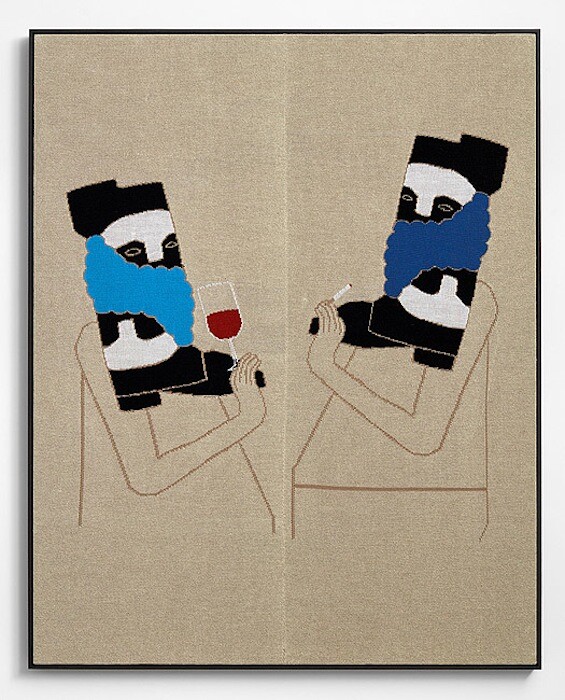

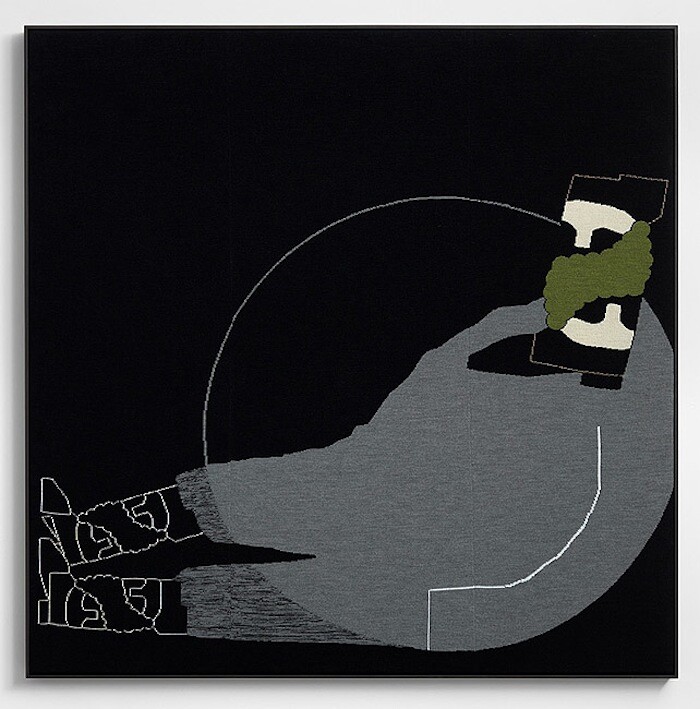

So’s tapestries are superficially comic scenes of jollification, intoxication, and indulgence. Going Out (2016) depicts two cartoonish characters having a good time: smoking, perhaps chatting, and drinking wine. Yet their faces are composed of black-and-white cowhide boots, their two halves joined by curly blue beards. So’s figures are literally two-faced, and perhaps this binary reflects divided states of mind or the multiple faces an individual has. In another knitted portrait, Circle (2016), a deep black backdrop is superimposed with a white-lined circle, perhaps a moon, which somehow sustains another odd two-headed creature in a reclining position. He wears a gray costume and head-shaped boots. But is this droll fellow drunk? Is he homeless? Maybe he is just having a nap. So’s canvasses are at once simple and beguiling, dreamy and conventional, psychologically charged and possessed of a whimsical sense of humor.

So’s and Noonan’s parallel exhibitions are connected by their craftsmanship and interest in forging together cultural elements from different spaces and times. Both exhibitions play with subjective states, ranging from the gloomy to the comically careless, and ask viewers to complete these fantastical narratives by adding a final layer to the composition: their own imagination.