Huma Bhabha’s humanoid sculpture In the Shadow of the Sun (2016), displayed on a low white plinth in a brightly lit room in London’s Stephen Friedman Gallery, stares at the viewer with inscrutable, smudged black eyes. The figure is female. She wears a hood. Her torso, cut from Styrofoam embellished with spray paint and oil stick, is colored a metallic blue-grey. The jagged breasts and pincer-like labia suggest this might be a fearsome goddess, worshiped millennia ago by an ancient civilization. Seen another way, this otherworldly presence could be an alien representative of a troubling future—a civilization yet to come.

That such sharply opposed interpretations are possible demonstrates the breadth and ambition of Bhabha’s work. In her sculptures, drawings, and collages, she incorporates elements of Greek kouroi, African tribal masks, and the sculptures of the Gandhara culture of northern Pakistan, which she mashes together with references to modernist sculpture. The artist cites Robert Rauschenberg’s “combines” as a key influence1, alongside the brittle figuration of Alberto Giacometti and Pablo Picasso’s assemblages, while more contemporary comparisons might be drawn to the rough-hewn figures of Georg Baselitz or Thomas Houseago’s iron rebar titans. That all these artists are male suggests that Bhabha is working consciously to disrupt a particular sculptural tradition. An obvious exception to that male-dominated lineage is Louise Bourgeois, and when Bhabha mutilates the female figure, she does so with a troubling directness which is similarly suggestive of physical violence.

Her solo show at Stephen Friedman comprises four sculptures, one painting, and four collages (all 2016). The work is consistently powerful and unsettling, yet the quartet of sculptures forms the most arresting element. In these works, the human figure is stretched, compressed, and contorted into strange, totemic forms. Menacing faces with hollow eyes leer from bulbous, oversized heads. Breasts and buttocks are slashed into jutting promontories of hardened flesh. The overall effect is of a series of mysterious artifacts from a parallel dimension or a long-forgotten past, or of Golems conjured to life from the lowliest of materials: brittle clay, discarded clothing, fragile Styrofoam, and cork. Yet alongside this foreboding atmosphere is the sheer joy of material juxtaposition. Walking around Bhabha’s sculptures, I was reminded of the children’s TV show Bitsa, broadcast on the BBC in the early nineties, in which chirpy, resourceful presenters would cobble together ad-hoc sculptures from household junk.

Across the room from In the Shadow of the Sun is a colossal female figure, over eight feet tall, made from cork, Styrofoam, and wood, decorated with paint. With her broad hips, prominent breasts, and spherical, boulder-like head, Castle of the Daughter bears a striking resemblance to the Venus of Willendorf (c. 25,000 BC), a limestone fertility icon from the Paleolithic era. Yet Bhabha’s sculpture is a victim of defilement, not just a towering icon of femininity. Her spine has been branded with a smiley emoji in black oil stick. Her nipples and belly button have been picked out, as if by a passing graffiti artist, with a few quick spurts of spray paint. Special Guest Star continues Bhabha’s interest in female forms imbued with threat or violence. Displayed in its own room, which enhances the starkly confrontational nature of the piece, this reclining sculpture is assembled from found objects arranged on a tilted wooden board: a paint-stiffened brush, a dirty t-shirt, and a scrap of patterned tin. At the top, where a head should be, two curved horns snarl from a gaping vulva sculpted in clay. Might this be read as a monstrously endowed vagina dentata? A Jungian archetype of feminine savagery? Or is it an abject creature—a sacrificial victim, perhaps—pinned to a plank by the violating force of the male gaze?

Bhabha invites such troubling questions, but confounds easy answers. Her work is certainly portentous, woven through with images of environmental catastrophe, ruination, and warfare. Yet she avoids polemical specificity, and her references are too eclectic to pin down to any one argument or cause. Instead, like a more pessimistic version of Joseph Beuys, there is a sense that Bhabha is operating as an artist-shaman: a figure who strives to unlock atavistic or primal forces through the medium of art. Where Beuys’s practice was rooted in his faith in the perfectibility of man—his signature materials, animal fat and felt, were symbolic of healing and protection—Bhabha’s is marked by an apocalyptic mood. Her craggy, looming sculptures resemble those dug up in archaeological sites only to be blown up by jihadists: relics of the old world threatened by the violence of the new.

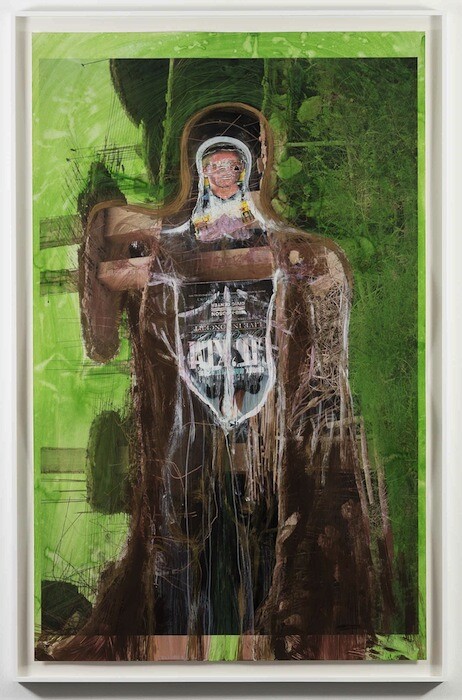

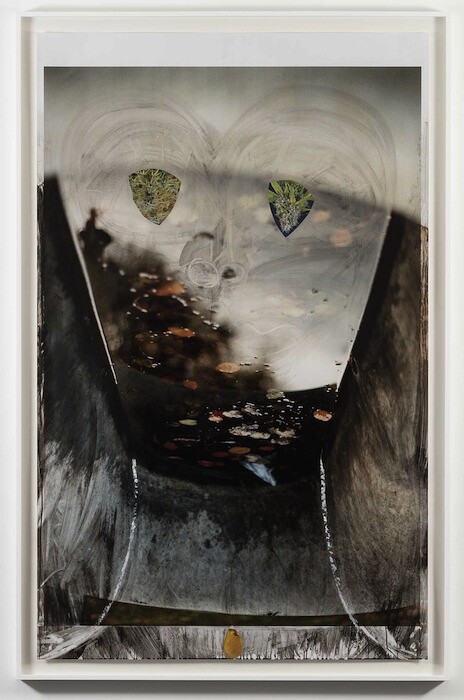

The anxious atmosphere that surrounds Bhabha’s sculptures is reflected, in a quieter register, in the four large-scale collages shown at Stephen Friedman (all untitled). In contrast to the hefty sculptures shown elsewhere in the gallery, the figures in these works have a tentative, ghostly appearance, picked out with sketchy marks and washes of thinned-out paint. Here, Bhabha embellishes photographs of dirty yards and pits of earth with ink and oil, overlaying her photographs with demonic faces, crude genitalia, and squashed, half-buried bodies. One of these figures resembles a zombie lurching out of a shallow grave. Another stares at the viewer with eyes of sticky marijuana buds, cut from the pages of High Times magazine, as if the freaked-out mood might simply be the result of a bad trip. In 2016, Bhabha’s work strikes an appropriately drastic, even alarmist note. In an interview conducted earlier this year2, the artist put it like this: “I’m from a broken place, living in a breaking world.”

Interview with Huma Bhabha, Art in America, (November 2010), http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/magazine/huma-bhabha/.

Interview with Huma Bhabha, Kaleidoscope, issue 27 (Summer 2016), http://kaleidoscope.media/interview-huma-bhabha/.