The latest feature of Spaces considers the Experimental Education Protocol on the Greek island of Nisyros as a mode to consider an alternative pedagogical case study.

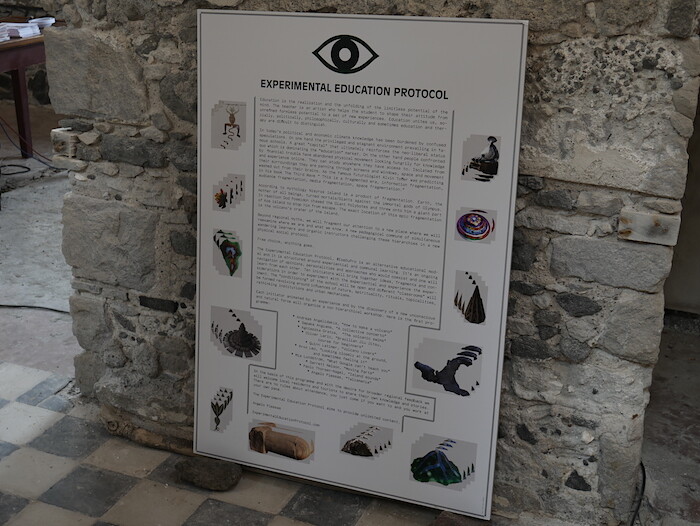

A manifesto published on the occasion of the Experimental Education Protocol, a meeting of artists and sympathizers on a volcanic Dodecanese island in the Aegean sea this past July, maintains that “sometimes education and therapy are difficult to distinguish.” Under the aegis of Sterna Art Project, artist Angelo Plessas organized a twelve-day retreat devoted to nonhierarchical pedagogy and “communal learning.” By the time I arrived to the island as an invited observer of the Protocol, halfway through its course, fellow guests had taken to using the nomenclature of formal education to organize undivided time, but in a way that didn’t especially seem to change the tone or direction of casual being-togetherness. A second-floor room of a century-old thermal bathhouse on the island’s north shore, windows facing the sea, became a makeshift classroom, while other, more exploratory learning was scheduled to take place in a variety of wilder locations. What isn’t pedagogy?

The Protocol’s guests were continuously participating in workshops. There was a relaxation workshop, where Plessas fitted residents with a headpiece that measured their brain signals in order to determine their level of relaxation. (Those tested were uniformly assessed as very relaxed.) There was a Brazilian jiujitsu workshop, where Oliver Laric gave one-on-one introductory training sessions on the coppery volcanic beach. There was a t-shirt workshop, where one could, if one felt like it, go to the t-shirt shop in town and have one or multiple t-shirts made with the help of the shop’s accommodating proprietor. This was likely my first indication that the only requirement for making an experience or a situation educational is the act of naming it as such.

Of the more formal workshops was one led by Quinn Latimer, in which she invited individual participants to join her in taking in the hot, salty waters of the island’s volcanic mineral baths in the bathhouse’s adjacent private stalls. From beyond a tiled partition, she read each person a specially chosen text, and asked them to read her one in return. Another was led by Sepake Angiama, who asked the Protocol’s residents to trace onto a large white piece of fabric an individual desire line. (Desire lines, in urban planning, name the vernacular paths created by foot traffic rather than by design, most commonly the quickest or most convenient route between two points.) Angiama then recorded these traces in differently colored embroidered thread. In-between and around these, there was a bee-keeping workshop, a talisman and amulet-making workshop, an anger management workshop, a toenail-painting workshop, and a dinner workshop, where Garrett Nelson recreated dishes from The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook (1954).

Another workshop, of Arvo Leo’s design, involved the stamping of euro bills with the image of a ginkgo biloba leaf in bright blue ink. I had brought two-hundred-some euros in various denominations for the trip, ten or so bills that Leo promptly imprinted with the shape. Before the end of the group’s time on the island, one stamped bill had already been recirculated back into the hands of a Protocol resident. When leaving I tried to break my remaining printed bills at Kos airport, anxious that the German shopkeepers I was returning to would be more reluctant to accept vandalized currency than their Greek counterparts, or would be less sympathetic towards the romance of the gesture.

Adjacent to the seaside bathhouse that hosted the residents of the Protocol was an abandoned one, identical but in disrepair. It became the site of an improvised exhibition that concluded the project, presenting artworks and ephemera evidencing the group’s tenure on Nisyros. A softly textured membrane—the resultant “flag” of Angiama’s desire lines workshop—hung from the ceiling in the building’s central hallway. Whereas a talisman by Frederik Exner Carstens—pumice stones beaded in the shape of an eye—had previously been very photogenic floating on the surface of the Aegean, here it took advantage of a disused bathtub. Leo’s Honey Thief (2016), a watermelon-head with a body of stuffed pants and shirt, sat propped up against a wall, crudely analogizing whatever the group was doing on the island—appropriating what it came across, assembling it into something by which it might feel represented.

On the penultimate night of the Protocol, musician Paolo Thorsen-Nagel shepherded participants through an exploratory sunset walk across the two craters of the Nisyros volcano. He carried a bluetooth speaker, which broadcast an original composition. Melodic and swelling in the deep of the volcano, the sound followed the pat of Thorsen-Nagel’s sneakers on the soft white earth through sulfurous fumaroles. What kind of learning is this? Plessas’s pedagogy emphasizes community-building over discourse, though of course these aren’t mutually exclusive.

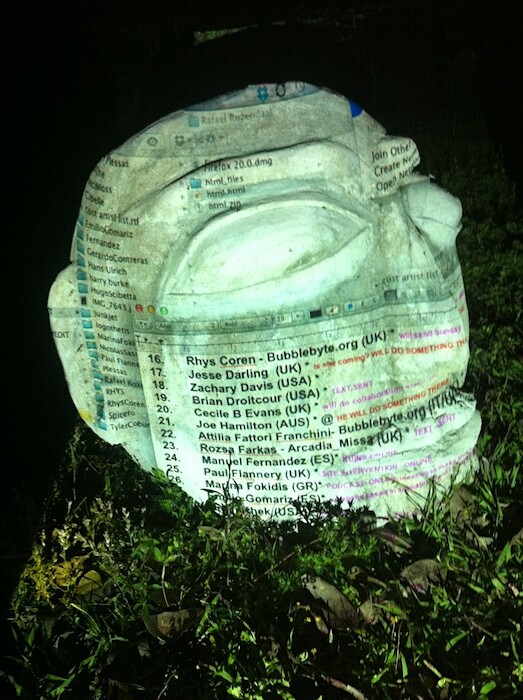

It’s a design that Plessas reproduces in much of his work, which for the last four years has included organizing the Eternal Internet Brother/Sisterhood, an itinerant annual residency program. The inaugural edition took place on the Cycladic island of Anafi, Greece, in 2012, and traveled to Las Pozas, a surrealist architectural park in Xilitla, Mexico, a seven-hour drive north of Mexico City, in 2013. In 2014 the residency was located in the North Dead Sea, in the West Bank, and in 2015, at the medieval Castello Malaspina in Fosdinovo, Italy. This past October saw the fifth edition of the Brother/Sisterhood take place in Sri Lanka’s Sigiriya jungle.

Each of these programs has brought together a number of artists, curators, and writers, many of whom, at least for the first iteration, had formed online communities dedicated to art and network circulation. Four years later, looking back at #EtInterBro’s list of past residents, it reads like a micro-history of the post-internet, where concerns once shared have subsequently fractured, and whose practitioners have evolved in wildly variant directions, towards different ends and economies. But the format, and its rotating cast of characters, allows for development and contradiction. While the Brother/Sisterhood is in dialogue with a long tradition of artists establishing intentional or autonomous communities, it’s made particular by the value it attributes to the digital in the practices and the lived lives of its residents. While residencies with locations similar to these—isolated from major urban centers and variously idyllic—sometimes signal a kind of cloistered retreat, prioritizing the immediacy of physical presence over virtual mediation, the discourse surrounding the Eternal Internet Brother/Sisterhood sidesteps any moralizing about how best to relate to others, instead acknowledging the fertility of communicating, at once, and prolifically, in several different modes.

A consequently huge amount of images, texts, and artworks have circulated through the proficient networks of EtInterBro, across which one finds a consistent aesthetic: they’re largely backgrounded by natural beauty, feature the figures or preoccupations of mostly young people, and are in some way in conversation with digital mediation, even if it’s just with a nod to the life of the viral image. The most iconic of these, in my own partial estimation, is a photo of artist Vincent Charlebois partially submerged upside down on the beach in Anafi, legs stretched upwards towards the setting, naked ass facing the camera (the documentation of a performance titled I ♥ the Universe and the Universe ♥ me, 2012).

With the Eternal Internet Brother/Sisterhood, as with the Experimental Education Protocol, manifesto-writing is a popular activity. In a promotional video for the fifth edition, Plessas provides the following voiceover: “Every year we communally detox from the effects of our neoliberal, post-technological life. We re-connect spiritually with antiquity and other eras, re-wiring our ‘homeless’ minds to a new visual beauty, the eternal beauty of our Mother Earth and its remarkable cultural commons.” In another recent project, conceived under the auspices of the public program of Documenta 14, Plessas took another author’s manifesto as the point of departure. Manifesto for the Noosphere (2011) by New Age writer José Argüelles predicts transcendence through collective consciousness, and formed the theoretical backdrop for a handful of Athens events planned under the rubric of “The Noospheric Society: Rituals and Attempts to Transform Consciousness,” a “communal society […] for people to rest in contemplation, in an altar of digital detox.”

Pedagogical initiatives have long been a way of experimental community-making, especially in the context of art education. Yet while Plessas’s projects refer to twentieth-century experiments like Black Mountain College, it’s more as a kind of spiritual predecessor than a practical model: they marry avant-garde practices with a cultish profile, but without the formal structure of an educational program. Instead, the language of pedagogy is employed in order to formalize lived experience as learning. While the stated goals of these projects vary, they understand mutual support and well-being as integral aspects of art-making, an idiosyncratic position that makes Plessas an increasingly important figure fostering a new generation of artists, both online and off.