It has been hard, lately, to think about art. I don’t mean to imply that art isn’t powerful, transformative, or even a necessary distraction. The problem, really, is that it’s been hard to think about anything besides the new president-elect, or how every check I deposit helps fund the poisoning of the sole water supply at Standing Rock. I live in Miami, whose intellectual capacity gets chewed over in yearly think-pieces, whose image is brushed clean and sold to people buying the high-rises that raise my neighbors’ rents, whose roadways become clogged with VIP BMWs each December. Yesterday, on the way to the Convention Center that houses Art Basel Miami Beach (ABMB), my Uber driver says she lived in Wynwood long before it—or ABMB—became “a thing.” “I watched my baby grow up,” she tells me, personifying both her neighborhood and maybe all of Miami. “She’s an adolescent now, changing fast. She’s wild.”

But the show must go on, even if pre-existing economic and racial disparities feel nails-on-a-chalkboard loud, even if the shiny lacquer of a trade show seems unusually ostentatious. There’s no real panacean balm to the problem, if it’s fair to call it a problem at all. We should care about art. In fact, we need to. It’s not business as usual, try as we might to pretend it is, and it was affirming to see that others thought so, too, at least in theory. Even in a world governed by the exchange of money, the product, one might pray, can still carry and drop the weight of the message, no matter how plush its landing.

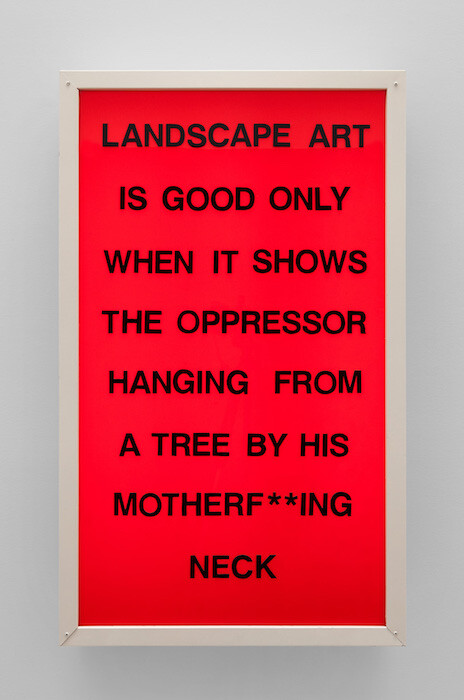

Immediately upon entering the fair, visitors behold Sam Durant’s End White Supremacy (2008) at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles: a huge, red lightbox of a sign, its title scrawled in black. His Landscape Art Sign (Emory Douglas) (2003) is named for the former Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party and reads: “LANDSCAPE ART IS GOOD ONLY WHEN IT SHOWS THE OPPRESSOR HANGING FROM A TREE BY HIS MOTHERF***ING NECK.” Someone will buy this piece. Someone will buy this piece and that someone may not care at all about black lives or about their own role in white supremacy. They may simply like electric signs.

But, at the end of a year rife with videos displaying those oppressors exercising their institutionalized power, it’d be irresponsible to not confront viewers with a harsh reminder, wherever its placement. At New York’s Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, the exasperation about our sociopolitical landscape, expressed with such brevity by Durant, continues. On the day after the election, Rirkrit Tiravanija created three massive linen canvases spread with copies of the November 9 edition of the New York Times: untitled 2016 (the tyranny of common sense has reached its final stage, new york times, November 9, 2016) (2016). The words are painted in acrylic and they are depressing precisely because they are true.

To be clear, in responding to injustice, self-reflection and self-care are just as crucial as a loud message. If we examine the legacies of our own families, our own bodies, might it speak to the troubled world at large? At Various Small Fires, Los Angeles, located in the fair’s Positions sector—spaces for curators to showcase a specific project by a single artist—Amy Yao’s installation addresses her familial history and, by turn, labor, manufacturing, and ecological racism. Yao’s mother, a fake flower wholesaler in downtown Los Angeles, is paid homage with Intercontinental Drift No. 5 (will it rain in the north, will it rain in the south, will it rain in the east, will it rain in the west) (2016) and Intercontinental Drift No. 4 (will it rain in the north, will it rain in the south, will it rain in the east, will it rain in the west) (2016), two plexiglas windows stuffed with bright artificial flowers, forever in bloom.

Below, there is a hillock of rice both real and fake, dotted with glimmering fake pearls. Entitled Doppelgängers II (2016), the piece recalls a 2015 scandal in China, in which rice producers bulked up the product with plastic. The impoverished communities eating it fell ill. Such scandals happen stateside, too. One need look no further than the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, the Exide arsenic leaks in Los Angeles, or the impending Dakota Access Pipeline—all of which have affected or will affect marginalized communities. A pile of polyurethane bones beneath the flowers, entitled Support II (2016), feels sinister.

Also of note is Keiichi Tanaami’s 16-foot Dazzling City (2o16) at NANZUKA, the Tokyo-based contemporary art space. Though literally dazzling (it glitters), the triptych is equal parts colorful and grotesque. Bloody-mouthed, demon-faced spiders climb atop kaleidoscopic rainbow buildings; bodies contort and flowers bloom. This, too, examines destruction. Born in Tokyo 1936, Tanaami experienced World War II as a child, and the experience seems frozen in a strangely childlike perspective, in which pain becomes cartoonish and oppression is a literal monster.

The profound nature of one’s own personhood—the identities one is assigned, the ancestral narratives one adopts—were explored with a gentler and necessary sensitivity, too, at Gallery SKE, the only Indian gallery at the fair. A sculpture by New Delhi-based Bharti Kher—My friend un-named (2014)—depicts the traditional Indian sari frozen in time: draped over concrete, the saris have been covered in resin, distilled and unmoving. Kher seems to simultaneously examine and revere this garment, inextricable from Indian tradition, simultaneously indicative of religion and race and individuality.

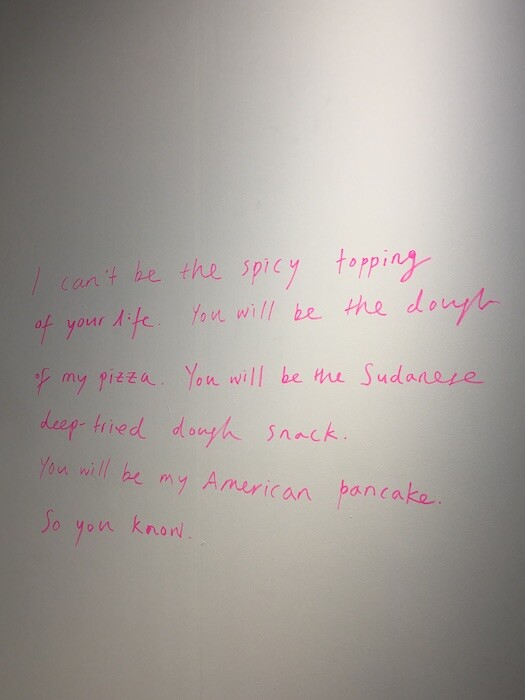

At the fair’s Nova section, where galleries display new work by one or two artists, Seoul gallery One and J. gives Chosil Kil the space to reflect on the multitudinous nature of her identity. The project, entitled I can’t be the spicy topping of your life, so you know (2016), features stuffed humanoid figures, their heads made of plush fish pillows, crawling or screaming or embracing each other on a patch of fake grass beneath an unfairly severed hedge. The fish-creatures are both land- and sea-dwelling; the lawn represents both interior and exterior space. Kil herself moved from Seoul to London; self-perception develops layers when we remove ourselves from that which once defined us. Large pink text on the booth’s wall reads, in a humorous but biting depiction of racial fetishization: “I can’t be the spicy topping of your life. You will be the dough of my pizza. You will be the Sudanese deep-fried dough snack. You will be my American pancake. So you know.”

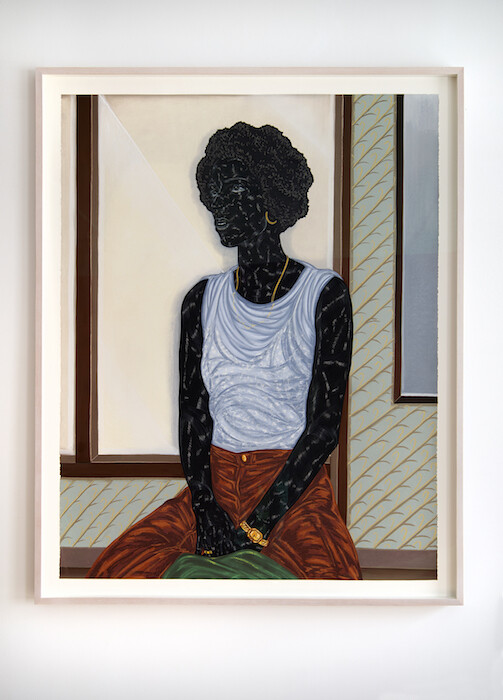

At Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, the subject of Toyin Ojih Odutola’s charcoal-pastel drawing, Six Months Later (2016), asserts and affirms herself, too, though it is less through her words than through her gaze. With Odutola’s signature white-and-gray-flecked brushstrokes, the woman’s skin looks like a galaxy, a cosmos of its own. Her gold jewelry shines, and she looks forward, away from us, and she seems to be cast in the light of a particularly subtle sun. It is enough that she simply exists. The fair also served as the debut of the gallery’s representation of Nina Chanel Abney, whose colorful acrylic-and-spray-paint works are playful, disjointed examinations of sex and race and communication and, perhaps, everything else. In one of her two displayed works, both To Be Titled (2016), light-skinned, blue-eyed men reach for and seemingly wrestle with each other while riding the backs of black men. One’s nose and another’s penis are as white as the men they carry. In the other image, two brown-skinned women and one man simply converse with each other. Their bodies are mostly free and, for now, carry no burden.

Before I left, I stopped by Galerie Lelong to see their exhibition of Andy Goldsworthy. His piece Hazel stick throws, Banks, Cumbria, 10 July 1980 (1980), a set of photographs depicting the artist throwing bundles of sticks, was soothing, in the way that staring at nature often is. Lelong also had on display Barthélémy Toguo’s Black Lives Always Matter (2015), a series of ten watercolor-and-ink portraits of young black men and boys—some as young as ten—killed by police throughout the United States. A chain dangling two wooden guns hangs in front of the images; the subjects are always, in effect, under threat. Even momentary escapism, I determined, was irresponsible, and I was relieved that even here it was impossible.