Fifty years after painting the earliest work in this exhibition, Suzanne Blank Redstone has her first solo show. The name may be unfamiliar, but her work at first glance appears to participate in a recognizably twentieth-century art-historical dialogue. Featuring primary-colored geometric forms and grids, her compositions instantly evoke Piet Mondrian, at the same time hinting at a venerable tradition of European pre-war geometric abstraction of the sort practiced by Jean Hélion. While her experiments with illusion and perspective take part in an even older lineage, there’s also a nod to Surrealism evoked by incongruous René Magritte-like clouds occasionally softening the otherwise hard-edge constructions.

Despite these superficial resemblances, the works in this show reflect less about art history than the artist’s own triangulation of space and color. Seven of the ten paintings and all of the drawings on display at Jessica Silverman Gallery derive from “Portal,” a series of 38 paintings made between 1966 and 1969, each accompanied by between three and ten preparatory drawings. In addition to the intentionally restricted red, blue, and yellow palette—relieved by black, white, and a grey mixed from the other pigments—Redstone’s formal vocabulary encompasses rectilinear shapes and grids aligned exclusively along 45 and 90 degree axes.

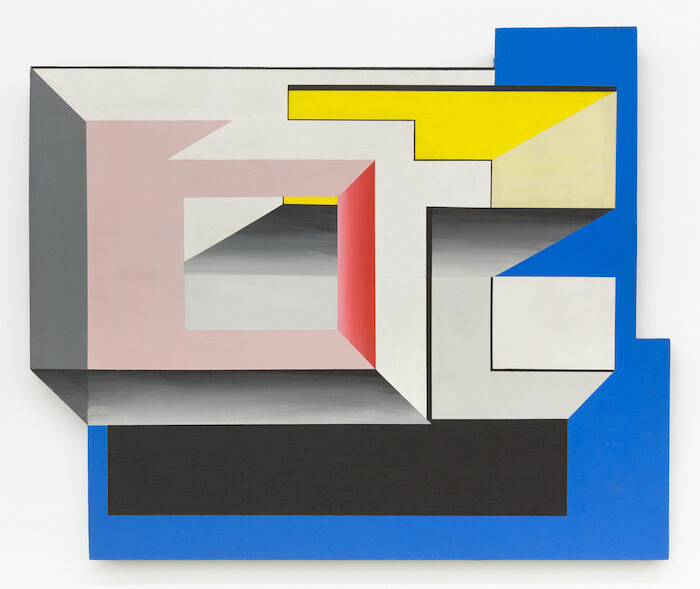

Setting these limits allowed the artist to focus on opening up space, or the illusion of space, in her compositions. These take shape in Portal 1 (1967) as a roofless pseudo-architecture of walls and windows, circumscribing voids that are lent depth by perspective, and continue with variations throughout the series. Seen from a mostly aerial vantage point, Redstone’s constructions appear unmoored, afloat against sky-like backgrounds, a phenomenon that is the actual focus of Floating Portal (1968). Their titles (“Portals”) hint at different temporal as well as spatial dimensions, and the overall effect is somewhat improbable and science-fictive.

Refuting the term abstraction, Redstone understands herself instead as challenging the materiality of paint in order to create primary situations in which space and form can interact. In the same way that visual poets such as Ian Hamilton Finlay use words and their physical appearance as building blocks, her starting points are pigment and panel. And while her artifacts are geometry and architecture, any resemblance, to a building, say, is incidental. Similarly, attempts to restrict Redstone to a single art-historical trajectory—beyond acknowledging that her painting was (like much other work made at the time) a reaction to the dominance of Abstract Expressionism—are misguided. The engine of Redstone’s work is internal, and concerns the exploration of space: each painting leads to the next. In Portal 8 (1968), for example, the latest work from the series exhibited here, a flash of pink marks the artist’s attempt to manifest light reflecting from the red quadrilateral immediately to the left. It is at once the clue and the prompt to her subsequent series of curvilinear reliefs, engineered to act as traps and mirrors for ambient light.

It’s also important to remember that these inquiries into space and color date from Redstone’s pursuit of an MFA at the University of Pennsylvania, having recently returned from a formative year spent in Rome. Now in her seventies, Redstone lives in the United Kingdom, where she relocated in 1970 following her marriage. Raising a family slowed down, but did not completely halt, her production.

The phenomenon of the re-emerging artist is not new or unusual. As early as 1984, in the inaugural Harold Rosenberg Memorial Lecture, Robert Hughes ascribed the “perpetual resurrection” of overlooked artists to the art market’s never-ending search for “product.” Describing the necessity to “study and endow [art] with a pedigree,” so as to “make it saleable,” he concluded provocatively that this is happening “despite the fact that the supply of good past art is dwindling and the supply of good present art is, to put it mildly, not getting that much more copious.”1

Hughes’s astute words echo through the intervening years, but they don’t tell the whole story. In 1984, art history had yet to reckon with the discourses of post-colonialism and globalization, both of which signaled a widening of its straight and narrow path. Less persuasive hereafter was the teleological trajectory described by Alfred Barr’s memorable museological diagram of art history as a “torpedo,” and more interesting the artists obscured by its exhaust fumes as it powered its way north and west.

Among these, of course, was an extensive female constituency. Engaging increasingly since the early 1970s with issues of visibility and representation, women artists tended (according to Judy Chicago, writing in 1972) to follow two paths: some worked “in almost total isolation, unknown to or ignored by the art community. Generally, these artists worked with subject matter connected to their home lives or their experiences as women…. Another group … whose work was more neutralized, were more connected to the art world [although] … their relationship … was quite peripheral and many of them complained of blatant discrimination.”2 Neither state of affairs was satisfactory, but both go some way to explaining why women—from Dorothy Iannone to Marisa Merz—are these days among the majority of “resurrected” artists.

Those of Suzanne Blank Redstone’s paintings on exhibition here are made with a convincing authority that does not announce them as either the work of a young, emerging artist in the sixties nor, necessarily, as an overlooked artist irrespective of gender. And while she may not fit neatly within an art-historical movement, Redstone shares with other artists—such as that grande dame of British abstraction, Bridget Riley—the project to inspire viewers to look closely, in her case at space. An intention that in today’s climate of overweening urban renewal seems once again relevant.

Robert Hughes, The Spectacle of Skill: New and Selected Writings (New York: Penguin Random House, 2015), 318.

Judy Chicago, Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist (New York: Author’s Choice Press, 1975), 99.