Adam Curtis’s new film HyperNormalisation (2016) is about the diffusion of power through the manipulation of the media. It posits that politicians adopted the basic tenets of techno-utopianism to create an oversimplified worldview of a global economic and political landscape which had become overwhelmingly complex. The creation of mass-mediated, caricatured villains, alongside the triumph of algorithms that create an echo chamber of opinion, reify the sense of felt anxiety and support new forms of power. Participation reinforces these structures, maintaining the fantasy of status quo in society even as we feel assaulted by the unpredictable.

Art fairs seem to operate in similar ways, spreading states of disconcert and powerlessness which reify comparable anxieties about the demands of the market whilst providing the grounds on which to idly fantasize about structures which could undercut the existing order. While the critique of fairs—writers pointing fingers at excesses, entanglements, or trends—only exacerbates the problem, we all fall into the trap of assuming that power lies in some displaced “other,” ignoring how our collusion enables the structures we seek to oppose. Display, discourse, commerce, and criticism all consolidate the fair’s encompassing power by refusing to acknowledge how normalized its ebbs and flows have become.

Alternatives do exist. Like Curtis’s narrative journalism—which interweaves surprising, and seemingly unrelated, events to tell political stories as they are felt and lived—the fair format, too, can take on an experiential, theatricalized tone. When Paris Internationale launched in a disused hôtel particulier near the Arc de Triomphe last year, it offered a similarly shoe-gazing, adolescent fair experience, which by disposing of a certain professionalism and polish opened up a promising alternative to the traditional format. Participants engaged with the limited space by staging performances in stairwells, innovating display solutions, and finding places to make out or make deals, thus rendering the market into a lived experience. Galleries spilling into one another, crowds spread out in comfort around the rooms: it felt unpredictable, but not overwhelming.

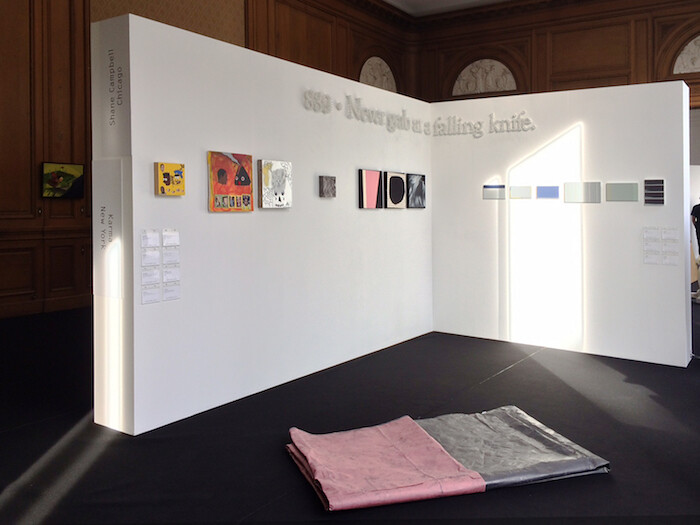

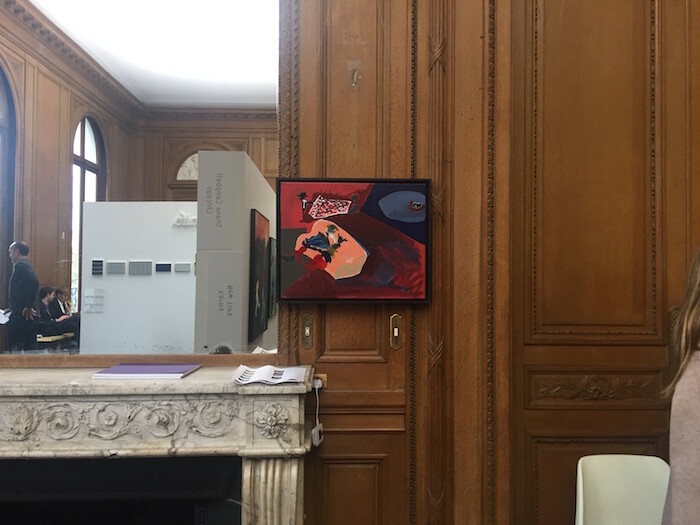

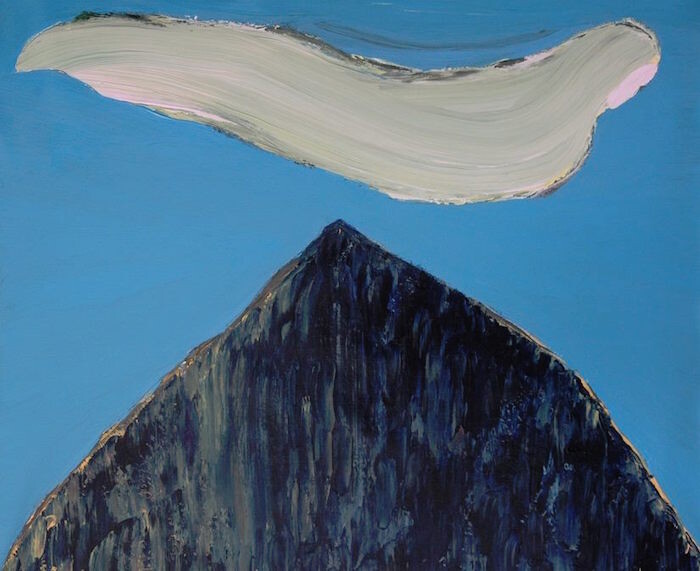

This year, however, Paris Internationale relocated to higher ground (literally up the block on Avenue d’Iéna) into another hôtel particulier, more dizzying and more troublant than the last. The 61 participants (54 galleries and 7 project spaces from 21 countries) found themselves neatly organized along three pristinely upholstered floors, not counting a lewdly lit basement allocated to younger spaces and non-profits. Whatever romanticism was held within the decrepit debauchery of last year’s fair, here felt lost (at least on the upper levels) to the grandeur of the venue. Paris’s High Art used the architecture to its advantage by highlighting the decorative language of the space: Cooper Jacoby’s honeycomb drops (Untitled, 2016) hung like sconces around a mantle, while Bradley Kronz’s thrift-store paintings (Without Men and Lost?, both 2016) were hung at an elegant museum-height on mauve walls. One down at New York’s Bodega, two cartoonish bottle openers by Andy Meerow (charm (yellow) and charm (blue), both 2016) were humorously enigmatic beside Alexandra Noel’s sweetly deadpan paintings (such as Rockabye Toilet Baby and It’s Like Going To Church, both 2016). That said, Bodega was precisely the kind of well executed booth that was dwarfed by its placement; a fate suffered to an only slightly lesser extent by its compatriot Karma in an adjacent room, whose mischievous hang made up for the otherwise conservative vibe of the surroundings.

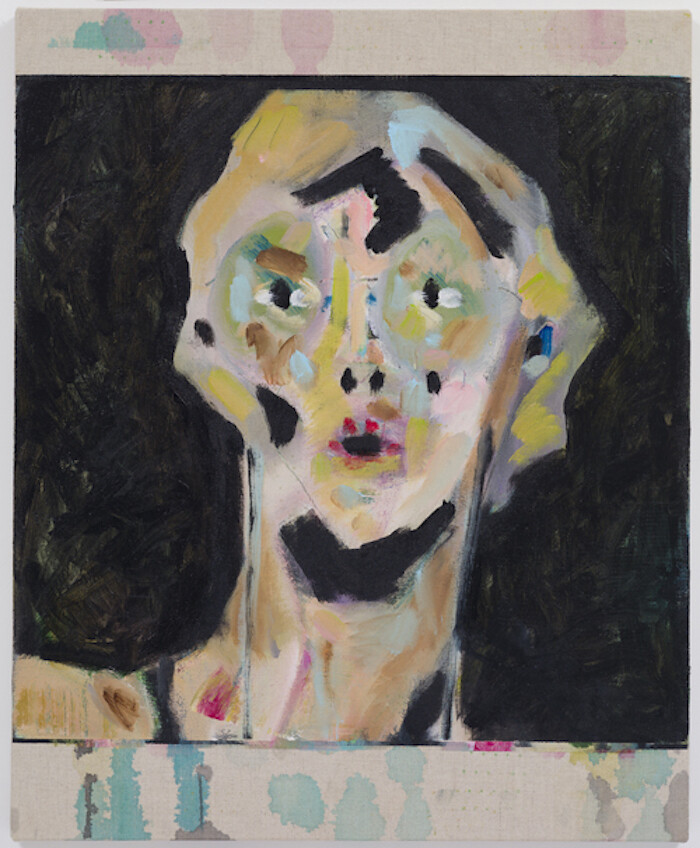

Offering a more conducive environment for dazed displacement was the tiled, windowless basement, which, with its encompassing Berghain-esque interiors, hosted 16 spaces inside its eddying layout. Sharing one of the rooms, Tokyo’s Misako & Rosen showed portraits by Kaoru Arima (Land Man, Nightforest, and Sunglass, all 2016) beside drawings by Lucie Stahl and David Rappeneau courtesy of New York’s Queer Thoughts. Paris-based non-profit Shanaynay adorned a narrow corridor with another edition of their yearly fundraiser (not to mention a refreshing, necessary acknowledgement of alternative economies,) with 25 works donated by the likes of Bjarne Melgaard, Kim Farkas, Louise Sartor, and Nathan Zeidman. Comfortably lodged in an alcove nearby was local Galerie Édouard Montassut, with new works by Guillaume Maraud (i.e.”a reward”, (upcoming) and i.e.”a reward”, (ongoing), both 2016) hanging on fixtures drilled, like everything else, straight into the tiled walls. Against the grim tiling in poor light, their pearl-lined romanticism caters to the possibility of an alternative fair that is structured so loosely as to let moods shift with individual artworks, as distinct from the overarching structure of the fair-as-storefront, fair-as-fair.

The upgrade speaks to the organizers’ shifting priorities, as last year’s successes are consummated in structures of presentation more typical of the bigger fairs. It is not the Grand Palais, but with a slightly shinier venue, more polished booths, displays verging on conservative, and a small pool of non-profits (and only one from Paris), not to mention the lurking presence of the Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard, Paris Internationale comes close to falling prey to the institutionalization it wanted out of. The casual, documentary photographs by Jean Baudrillard at Chateau Shatto, Los Angeles, offer up a warning: we live in a world with more and more simulation and less meaning. To Baudrillard, photography was a window to the non-objective world; these photos cut through the fiction of comfort provided by the market and flood the basement with (no) meaning.

FIAC’s 189 galleries are laid out the same way as last year, with some minor corrections. The fair still overwhelms visitors with its manic pace, sacrifices the autonomy of artworks to an engulfing set, and promotes a simplified, financially secure, and complacent model of interaction. Yet, all the same, FIAC’s predictability ensures that galleries continue to participate: it offers the blind comfort of an established clientele, familiar procedure, and surefire sales, becoming a mechanized production which re-presents, in an enclosed area, all the messy complexity that constitutes the art world. Retreating into this false security, however, fails to acknowledge an “outside” that is increasingly precarious and unpredictable. Its complexity can no longer be carried by the fair, let alone disseminated by it. The art world is elsewhere, and FIAC a sad surrogate. Whilst wandering around the fair, I asked an artist whether he was showing with anyone: “In a few booths,” he said, “but it’s not about me anyways.” I digress.

What is lost in that model is an acknowledgement of the potential affect of that “outside,” as touchy and vulnerable as it is. My cynicism was undermined by the display at Cologne’s Galerie Buchholz, where I was faced with a untitled, chocolate bar-esque Vincent Fecteau piece. Lured into its folds, I had a vague recollection of my first time at the fair, eager simply to see things I hadn’t seen before. Those encounters are still possible: a moment of clarity peering into the watery basin of a Roni Horn piece (Untitled, 2016) at Xavier Hufkens, Brussels; a miniature, wooden, zigzagged sculpture that turned out to be a Judy Chicago at San Francisco’s Jessica Silverman (Small Slatted Sculpture, 1961); bright Pink Panther paintings by Katherine Bernhard (Running Pink Panther, 2016) at Canada, New York; William N. Copley’s paintings (such as Untitled, 1978) at Venus, also from New York; a surprisingly intimate and painterly portrait of Alex Israel’s mother at New York’s Reena Spaulings (self-portrait, mom, 2016); and last but not least, a weird, stringy Jessica Stockholder poster-cum-installation (#622 Palpable Glyphic Rapture, 2014) at Nathalie Obadia, Paris. Though in writing this, I fail to address my own participation, I also notice an opportunity: if hypernormalization is a product of complacency, perhaps looking can be a mode of active engagement or, more simply, a new mode of participation. As Curtis declared in promising optimism: “Maybe this feverish atmosphere we’re in is part of the transition to a genuinely new kind of society, from which a new kind of politics might emerge.”1

Alex Miller, “The Filmmaker Adam Curtis Shares His Thoughts on Our Generation,” VICE (December 7, 2012), http://www.vice.com/en_uk/read/looking-beneath-the-waves-v10n12.