It’s a sunny autumn day in the small Japanese city of Okayama, and two British men born in the 1960s are conversing about cameras. Liam Gillick and I both own the retro-looking Fujifilm X-Pro1, which we’ve chosen for its impressive price-to-performance ratio. “I’ve used it a lot in my work,” a ruddy-faced, relaxed, and sunglass-wearing Gillick tells me. I show him how I’ve retrofitted mine with Wi-Fi. Gillick—perhaps sensing that we’ll also share an interest in the reassuring Brutalist architecture of our youth—tells me that the Okayama Art Summit I’ve come to review, which he’s spent two years curating, takes place in some very distinguished concrete buildings, several of them designed by local architects and now threatened with redevelopment.

This turns out to be the case: the pleasure of my two days in Okayama, map in hand, comes just as much from the exploration of four or five fabulous late modernist buildings as from the art inside them, although that’s very much to my taste. There are also traditional sites: Angela Bulloch’s posters proclaiming the principles of the 2012 UN Rio Earth Summit adorn the walls of an old soy sauce factory, and Jorge Pardo’s miniaturized, simplified Neutra house stands in the shadow of Okayama’s sixteenth-century castle. The ironic resonances are presumably intentional: the UN’s principles could be seen as a tasty condiment sprinkled on world trade, and the contrast between Pardo’s modernist structure and the building behind it vanishes when you discover that Okayama’s castle was actually rebuilt in concrete in 1966.

The “summit” is a new triennial that shares its venues and tasteful European curatorial style with a precursor called “Imagineering,” held here in 2014. The Okayama region is fully aware of the power of art to spearhead economic regeneration: the past decade has seen an astonishing art-led transformation of the islands of the Seto Inland Sea. In a benign form of gentrification, geriatric de-industrializing islands like Naoshima and Inujima have been turned into cultural tourist attractions, equipped with world-class museums and interesting installations by artists like Shinro Ohtake. Okayama is the ideal city for day-trips to this appealing archipelago.

Gillick has chosen work by his friends and his generation, and hasn’t been ashamed to admit it: the first thing you see when you arrive at Okayama Station is a gigantic poster in the style of Experimental Jetset’s 2001 t-shirt “John & Paul & Ringo & George.” Gillick’s take, in Helvetica that covers the whole facade of the building, reads: “Yu and Trisha and Noah and Robert and Anna and Peter and Angela and José León and Michael and Peter and David and Simon and Ryan and Melanie and Rochelle and Dominique and Pierre and Joan and Tatsuo and Katja and Ahmet and Jorge and Philippe and Rachel and Cameron and Shimabuku and Motoyuki and Rirkrit and Anton and Hannah and Lawrence and Anicka and you…” Plenty of these are his artists, his team, his clique.

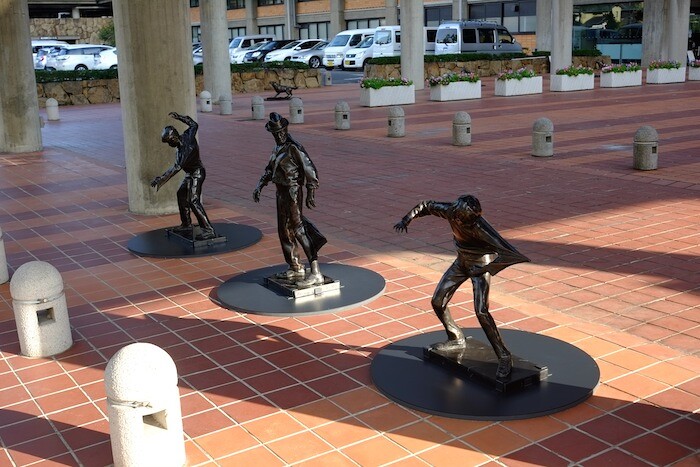

Many of the works are undiminished by the fact that I’ve seen them before on the international art circuit. Pierre Huyghe’s film Human Mask (2014)—in which an uncannily girlish masked monkey potters around a post-apocalyptic restaurant—certainly has less impact in the crush and scurry of a Western Huyghe retrospective than it does here in an empty room in Kunio Maekawa’s elegant Hayashibara Museum of Art building. It’s empty because Okayama is a town without an educated contemporary art public. An old Japanese man greets me as I sit in front of an LED sculpture by Philippe Parreno (With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life, 2014) that pokes from the moat around a municipal library; the slim billboard flickers with semi-abstract plant imagery and emits an unsettling series of sounds. “Is this your work?” the man asks in halting English. “No, it’s by a French artist.” The man’s modesty covers a flicker of disdain: “It’s very difficult to understand,” he says, and moves off. Across the road Ahmet Ögüt’s bronze sculptures (While Others Attack, 2016) of police attack dogs savaging protesters (wittily separated, as if by an obfuscating official report) seem to mock the municipal government offices. This is a country where such things haven’t happened for decades.

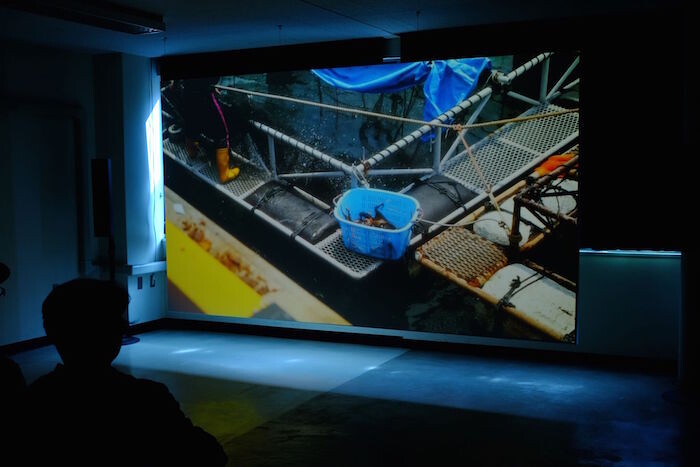

The fact that staff outnumbered visitors in all the venues I visited suggests that the old man’s attitude is widely shared across this placid and beautiful city. It’s not as if the artists are speaking of foreign things: Parreno and Huyghe in particular have been hugely influenced by Japan, and Human Mask is by far the best work of art to have emerged from the Fukushima disaster (though it’s about much more than that). Elsewhere there are more blatant attempts at local relevance: Yu Araki’s Wrong Revision (2016) is a history, told in video and installations, of hidden Christian symbolism in Japan, and specifically the Portuguese introduction of dried seafood, which led to the Japanese “crucifying” octopus on sticks: a symbol, apparently, of both the devil and Christ. Tatsuo Majima’s 281 (2016), which takes on the plastic mutability of the local folkloric figure of Momotaro, the famous Peach Boy whose statue stands at Okayama station, is all the more resonant for being staged in the city’s most beautifully unplastic, immutably Brutalist building, Kunio Maekawa’s pilastered, yellow-bellied, angular Tenjinyama Cultural Plaza.

It was the video work which stood out for me: mesmeric, oblique, and familiar pieces by Joan Jonas (They Come to Us Without a Word, 2015), Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster (Sommer Kino, 2015), and Rachel Rose (Everything and More, 2015) were good to re-watch in empty rooms. Unfortunately, Gillick’s own work for the show—a big cladded chimney in his trademark orange tones (Faceted Development, 2016), a playable crazy golf course (Development, 2016), that poster at the station—smacked of bluster and gimmick, qualities previously left to the lesser but better-known artists he went to Goldsmiths with. Gillick’s curation in Okayama was better than his art. The “development” theme must have been chosen long before the current political landscape of populist authoritarianism came sharply into focus, but it resonated. As Dawn Chan points out in an introductory text in the catalogue, “development” implies something positivistic, some demand for measurably objective improvements, something not usually associated with art. And Gillick’s own essay starts by admitting a certain bourgeois guilt about the privileges of those of us who can enjoy endless self-development. But in our current “post-factual, post-truth” era, in which a declining cosmopolitan neoliberalism (represented here by sponsoring banks like Credit Suisse and Nomura) starts to look positively benign beside the toxic new forms of xenophobia and isolationism now rising, I found it both refreshing and reassuring to see a case being made for contemporary art—that protean, oblique, passionate, and esoteric form of visual poetry—as a form of education, empathy, knowledge, enlightenment, and improvement. Whether Okayama was “receptive” was moot; the autumnal, retro-tinged Japanese city felt perfectly positioned to capture the belated sonic boom, the delayed radio waves, of the best of the old West—its liberal-progressive culture, its cosmopolitan reach, its soft power—just as a brutal and jarring new clamor threatens to drown out those sweet sounds forever.