Spaces is a feature of art-agenda that proposes a thematic examination of galleries based on the analysis of their physical and spatial configurations. Every two months, art-agenda publishes a new reflection on the spatial characteristics of galleries, their architecture, identity, and relation to their historical and geographical context. The sixth iteration of Spaces explores the storefront gallery.

Let us presume that there is a substantive difference between a “store” and a “gallery,” and that one might occupy the other (either parasitically or symbiotically) in a manner somehow distinctive, and see if this holds up as a hypothesis. As defining characteristics of the store-as-gallery, I suggest the following: an architectural space with street-level, pedestrian access, existing in the context of other commercial retail outlets, and conspicuously deploying plate-glass picture windows that theatricalize the goods, or artifacts, contained within.

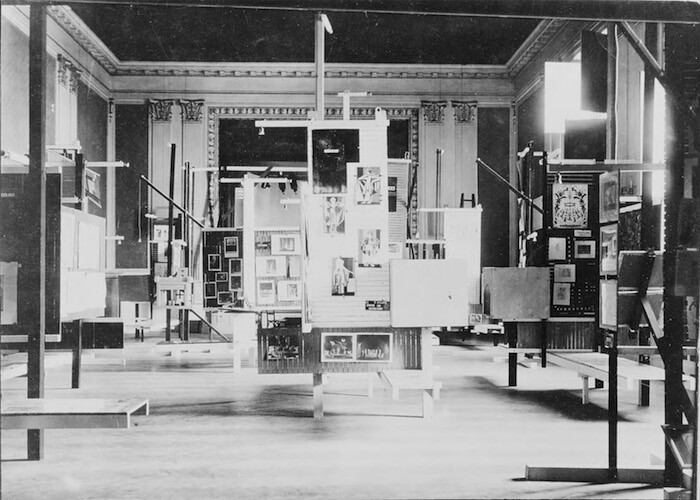

Let’s start with some background to this apparently familiar form, in 1851 at the “Great Exhibition of Works of Industry of All Nations” held at the newly erected Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park, a useful coincidence of a number of the political, technical, and commercial concerns that will have great ramifications for the design of both stores and exhibitions as we recognize them today. For the first time on this scale, and in an overtly public way, the “Great Exhibition” stages all manner of different valences of object, machine, industrial process, raw material, and fabricated product, all competing for both trade and casually distracted interest while also performing as a self-contained temporary monument to imperial power. Rather than enclosing singular items in clustered display cabinets, architect Joseph Paxton’s rapidly fabricated demountable structure—made possible by advances in sheet glass and cast-iron manufacture(1)—demarcated all of its contents as both of note and of implicit value, clearly lit and dramatically displayed. (An anecdotal measure of the success of these new viewing conditions: as many as five times the number of people paid to see the casts of the Elgin Marbles in the Palace’s second location in Sydenham, alongside well-designed household wares offered for sale, than saw the originals for free in the notoriously dingy British Museum.)1 By taking on the conditions of a vitrine at architectural scale, Paxton’s Crystal Palace enunciated many of the key design concerns that would vex museum and department store designers (the latter a format then gaining in traction, particularly in France) for years to come.

“Any store in a modern town, with its elegant windows all displaying useful and pleasing objects, is much more aesthetically enjoyable than all those passéist exhibitions which have been so lauded everywhere.” —Giacomo Balla, The Futurist Universe, 1918.2

The challenge of performative facades and a new, transparent architecture that theatricalized both goods and customers (and the new form of publicness it gave rise to) appears to have caught the imagination of artists from the second decade of the twentieth century: Surrealists extending their visual contextualization of publications from their jackets to the windows that displayed them (from René Magritte’s 1934 cover designs for André Breton(4) to Marcel Duchamp’s 1945 window display for Brentano’s bookstore in New York, again for a publication by Breton); the Futurists championing the consolidated display of industrially manufactured artifacts (Giacomo Balla’s attitude was not atypical—Fernand Léger was to celebrate the elaborately composed artifact’s “inutility” in this context in his “Notes on Contemporary Plastic Life” of 1923); and the Constructivists’ and the Bauhaus’s willing fluidity between “fine art” and industrial design (Aleksandr Rodchenko and Vladimir Mayakovsky’s agency Reklam-Konstuctor [Advertising-constructor], for example).

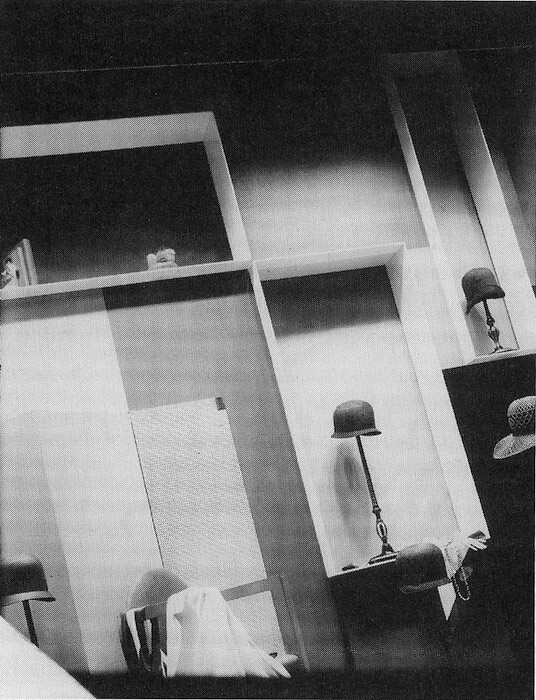

Emerging from a Constructivist context, Austrian-born émigré Frederick Kiesler explicitly embraced the shared ground between aesthetics, fine art, and commodity display. Kiesler’s window designs for Saks Fifth Avenue in New York (1928) were his financial salvation and revolutionized commercial window display in the process.3 Gone were the typological cavalcades of the kind documented by Eugène Atget in Paris, and in their place was an all-encompassing visual system running the length of the building’s façade, 14 interconnected window spaces built into an abstracted theatrical set, staging select items (a single jacket draped over a chair, say) as fetishized elements within a singular idealized context. The uncluttered and unashamedly aestheticized modernity of the presentation was a sensation, the three-week commission remaining installed for the next nine years, and so successful that in 1930 Kiesler was able to publish an intelligent guidebook, succinctly titled Contemporary Art Applied to the Store and its Display.4 Despite the store’s historical obligation to exhibit a myriad of wares to a passing crowd, Kiesler realized that what it contained for sale would be favorably preconditioned by the desire already projected across the glass of the façade; the first transaction would be sealed in the street. Three blocks north, in 1934, Phillip Johnson’s provocative “Machine Art” exhibition at MoMA would further muddy the water with its elegant display of mass-produced, machine-fabricated artifacts, with both catalogue and wall labels including details of where each of the exhibits could be sourced and at what unit price, with the smaller, cheaper items being available for the public to handle.

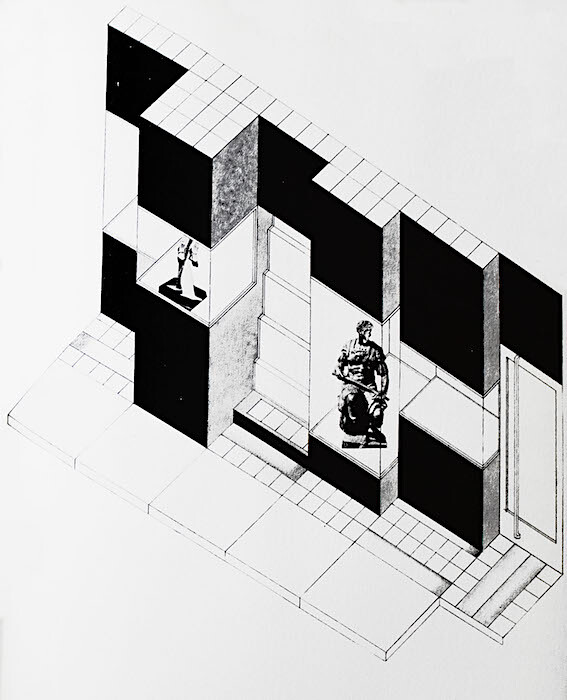

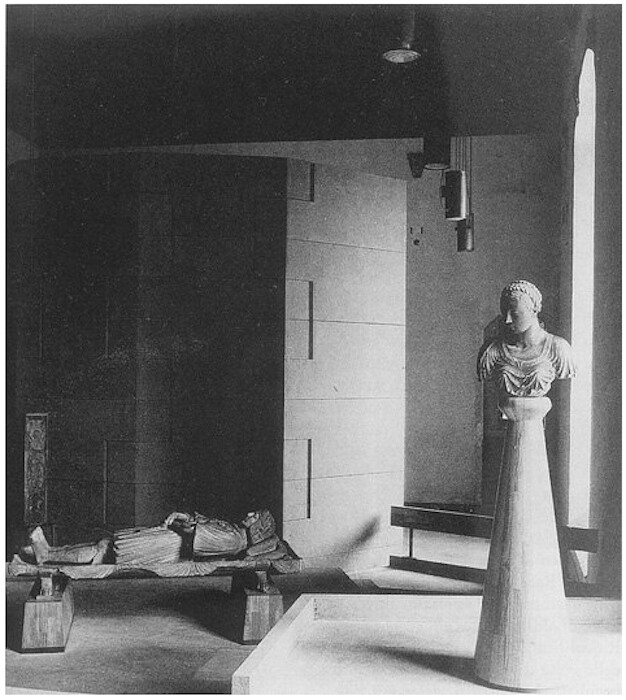

Through the 1940s and ’50s, a number of Italian architects would further revolutionize display techniques and perpetuate this oscillation between commodity presentation, store design, and re-orchestrations of classical collections. By taking objects out of vitrines or off defensive staging platforms and articulating them in a shared, dynamic architectural space, these designers idealized and aestheticized the museum as a container both of intrigue and value (in all senses of the word). Carlo Scarpa’s use of strategically hung colored blanking plates to pick out selected profiles of sculptures floated on slender pillars, for example, or Franco Albini’s pneumatic articulations of classical fragments in space were spatial conceits that were also applied to store designs for Olivetti (in Venice in 1957 and Paris in 1958, respectively), amongst Scarpa and Albini’s other commissions.5 In New York, another Italian design practice, BBPR, would once again cause a public sensation on Fifth Avenue by inviting members of the public to encase themselves in a vitrine: open to the street but apparently framed from within the store, the concession for Italian typewriter brand Olivetti blurred the boundary of inside and outside, creating a very public exhibition of the desirability of a luxury product, articulations of intimacy and spectacle familiar from BBPR’s redesigned exhibition displays at Castello Sforzesco in Milan (1954-6). Having moved from Italy to Brazil, architect and curator of the São Paulo Museum of Art Lina Bo Bardi did away with walls altogether (also an obstruction to Kiesler’s theories of Tensionism)6 with her staging of the museum’s historical painting collection on individual glass sheets—each economically clamped at its base in a cube of concrete.7 were removed and destroyed in 1996, and re-fabricated and re-installed by MASP artistic director Adriano Pedrosa in December 2015.]

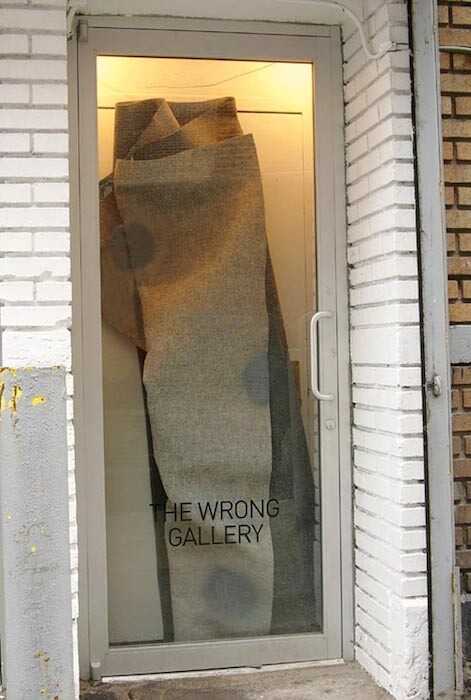

In the UK, moves by the so-called YBAs in the late 1980s to co-opt both the empty real estate and commercial logic of retail spaces set the tone in the following decade for local councils to reinvigorate the proliferation of vacant units in shopping areas by offering short-term leases to artists in what has now become a prosaic quid pro quo of urban gentrification. It is hard to see how even long-term projects can escape these market forces—stepping into the Dia-commissioned and maintained The Broken Kilometer (1979) by Walter De Maria in New York recently, the real-estate pressure of the swarm of upmarket boutiques that surround it is palpable, the preservation of a space for (non-monetized) contemplation seemingly untenable in such an environment. These concerns had been archly theatricalized by Maurizio Cattelan, Massimiliano Gioni, and Ali Subotnick’s Wrong Gallery project (2002–05), living parasitically in two and a half square feet of exhibition space behind a permanently closed glass door onto the street (actually the back door of Andrew Kreps gallery in Chelsea, New York) and hosting compact exhibitions until they, too, were evicted. Jennifer Bolande’s West of Rome Public Art project intervened in this boundary between forced removal and gentrified re-leasing, occupying vacant real estate along LA’s Wilshire Boulevard. The defensive patina of plywood sheeting that separated vacant commercial properties from the street was moved back behind their sheet-glass walls, staging a material surface more familiar to eviction or riots as luxuriously printed, undulating drapes of fabric that concealed the space within (Plywood Curtains, 2010).

While in many regards the architecture of commercial sales seems to have progressed very little from deals done behind a velvet curtain—the maintenance of the exclusive arbitration of surplus value demanding that there is always one further door through which access is denied, a convention made more public and awkward by the contemporary proliferation of art fairs—the shift in nomenclature from “private” to “commercial” gallery underlines the exponential demand for landmark galleries and public visibility. This relationship to the public realm is seldom used engagingly, the challenge of vitrinized space often being obviated by covering the windows with vinyl, or the default stud walls. Paul McCarthy’s installation Pig Island (2003–2010), part of the artist’s 2011–12 exhibition at Hauser and Wirth (“The King, The Island, The Train, The House, The Ship,” which occupied the gallery’s two London spaces, in Piccadilly and Savile Row), at least engaged wryly with this context: units of studio detritus on pallets (many on wheels, no less) both evoking a wonderfully decluttered studio back in California and taking the form, on the historically mercantile Savile Row, of an extremely upscale yard sale.

Conversely, apparently taking a lead from Kiesler’s writings on the possibility for a building’s façade operating 24 hours per day, Los Angeles’s Farago gallery has been staging exhibitions to Downtown’s pedestrian shopping traffic day and night since opening in three former jewelry stores on West 8th Street in 2014. Because of the shallowness of the three adjacent glass-fronted shopfronts, works remain visible and well-lit around the clock. During William Crawford’s exhibition “More Worried than a Worm in a Bird’s Nest” in early 2016, the subtle dissonance between the gallery and its surroundings was amplified by the elegant display of pornographic drawings, just legible from the sidewalk.

This visibility and familiarity of context has been exploited to even more democratic ends in artist and curator Noah Davis’s Underground Museum in Arlington Heights. Founded with his wife, artist Karon Davis, in 2012, the gallery occupies a series of connecting storefronts in this working-class area of Los Angeles, and was established with the intention of bringing a “high-end gallery into a place that has no cultural outlets within walking distance.”8 His now renowned “Imitation of Wealth” exhibition from 2013 refabricated major works by Jeff Koons, Robert Smithson, Dan Flavin, and other luminaries in what was, in many ways, an entirely conventional exhibition of modern masters had it not been for the unconventional provenance of the works (for example, the vintage Hoover for Imitation of Jeff Koons [2013], a copy of the 1980 work New Hoover Convertible, was sourced for 70 dollars on Craigslist) and its context. The exhibition’s cyclical re-incorporation saw it re-installed in Los Angeles at the MOCA’s own new Storefront for Art project before Davis’s untimely death last year. That this exhibition, through Davis’s negotiation, has established a reciprocal loan relationship between these two institutions is a considerable legacy, though it remains to be seen what identity this new space created by MOCA will be able to forge, disappointingly staged on a gentrified plaza opposite a gift shop and terraced café—though MOCA Chief Curator Helen Molesworth’s intelligent rehang of the museum’s main collection suggests that this context may yet be productively parasitized.

The recognition and re-evaluation implied by this new project, of a now-ubiquitous but often underexploited form, appears to be a positive move in light of its historical legacy. It remains to be seen however if commercial galleries, and indeed artists themselves, have the desire (and time, budget, courage) to engage with and exploit the architectural potentials of an adopted typology with Bolande’s, or Michael Asher’s (for example, June 8 – August 12, 1979, The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Illinois) clarity of purpose, nuanced relationship to context, and formal dexterity.

(1) Advances which, in coincidence with the lifting of punitive levies on glass and the repeal of the window tax, would lead to the proliferation of plate-glass “picture windows” in the architecture of commerce in the years that followed.

(4) “…an image of this kind is not likely to pass unnoticed in a bookstore window,” wrote Magritte in a letter to Breton on his design for Breton’s 1934 pamphlet “What is Surrealism?” in Magritte to Breton, June 22, 1934, in René Magritte: Catalogue Raisonné, vol. 2, David Sylvester, ed. (Antwerp: Mercatorfonds and Houston: The Menil Foundation, 1993), 30, quoted by Welchman, ibid. René Magritte established the advertising agency Studio Dongo with his brother Paul in 1930.

See Kate Nichols’s excellent essay “Art and Commodity: Sculpture Under Glass at the Crystal Palace” in Sculpture and the Vitrine, John C. Welchman, ed. (Farnham: Ashgate/The Henry Moore Institute, 2013), 23–46.

Giacomo Balla, The Futurist Universe, 1918, cited by Welchman, ibid., in Umbro Apollonio (ed.), Futurist Manifestos (New York: Viking Press, 1973), 219.

A similar combination of pragmatism and opportunity would lead Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns (as freelance window dressers through the 1950s), James Rosenquist (1959), and Andy Warhol (1961) to develop window displays for Bonwit Teller in New York, following Salvador Dalí’s controversial commission in 1939.

Frederick Kiesler, Contemporary Art Applied to the Store and its Display (New York: Brentano’s, 1930).

See, for example, the renovation and installation design by Carlo Scarpa for Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo (1954), and by Franco Albini for Palazzo Bianco, Genoa (1951).

“NO MORE WALLS!” Kiesler, ibid, 30.

The original cavaletes de vidro [glass easels

Yael Lipschutz, “Links: Q+A with Noah Davis,” Art in America, March 11, 2013, http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/interviews/noah-davis-roberts-tilton/.