In 2015, Spain’s Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy declared that the financial crisis, which began when global markets collapsed in 2008, was over, but that its legacy still endured.1 When recession hits, luxury goods dealers are among the first to panic, and the art market is no exception; luckily for Spain, government funding has kept cultural initiatives afloat. Even ARCOmadrid, the country’s main fair, which is one of the best attended in the world2 and comparatively hosts the most expensive VIP program, only managed to sidestep the recession because it is heavily subsidized. But beyond the temporary glamour and inflated sales reports, net profits on the global fair circuit are often meager, especially for small or mid-size galleries. This model is proving hard to sustain and puts the squeeze on gallerists to look for alternatives. This year, the seventh annual edition of Apertura Madrid Gallery Weekend, organized by the Art Galleries Association Arte_Madrid, substantially expanded its program in an effort to put Madrid’s gallery scene on the international map, bringing in for the first time collectors, curators, residency organizers, and journalists to visit over 43 solo and group exhibitions across the city.

Conversation about local versus global art networks arose multiple times throughout the weekend, as well as those referring to the trend of wealthy South and Central Americans coming to buy property and do business in Spain since the markets crashed. Countries on both sides of the Atlantic have been tapping into each other’s networks, which was mirrored by the exhibitions on view.

NF/Nieves Fernandez Galería, for example, invited Mexican artist Omar Barquet and Argentinian artists Mauro Giaconi and José Luis Landét to curate a group show of their own work. The artists make process-based work, focusing on politics, history, and authorship. Their exhibition “Entrecejo” uses art to “approach the game as a conflict” (as described in the press release), incorporating rough, deconstructed elements such as a flea market painting ripped into strips, rehung as a textile piece (Landét’s Bordes, 2016) and plywood panels loosely carved with craggy lines and drilled with holes (Barquet’s Twilight, 2016), which hang in front of the gallery windows, letting in traces of light. In the back room, the artists set up a betting game common to Mexican construction sites and bars, in which coins are thrown into a hole, and invited audiences to play. The jarring, momentary sound of the coin hitting the box was amplified into the main gallery, enhancing the aggressive actions performed on the materials. Like the sound, their actions are presented as passing memories.

Parra & Romero exhibits nostalgic, conceptual work by Argentinian artist David Lamelas in a show titled “Intimidad Territorial,” including his fleshy pink sculpture Piel Rosa (1965)—of a shelf, a beam, and a hollow box using inversions of geometric perspective—and Vortex (2016)—an aluminum cone set face down in the corner alongside a pencil-on-paper drawing of an inverted cone in a seascape, funneling water into its empty vortex. Combined, the two sculptures offer subtle meditations on the contrasts between the simplicity of definitive form and the mind’s projection of infinite space. In another room there’s the projection of the video Lectura (Labyrinths de J.L. Borges) (2016)—a Spanish-language remake of an earlier English version called Reading (1970). The silent video shows a young woman orating an excerpt from Jorge Luis Borges’s 1946 essay “A New Refutation of Time” with the text appearing as subtitles. A sequence of framed video stills surrounds the room, delineating the text. If anyone can still quote Borges, whose work has been overused by contemporary artists to the point of cliché, it’s Lamelas, whose simple gesture of fracturing time and memory between what is seen and what is read and understood still passes as an enchanting poetic homage to the author’s ideas.

A historically significant group show of modern abstract painting and sculpture by Gerardo Rueda, Jordi Teixidor, Gustavo Torner, José María Yturralde, and Fernando Zóbel, who were internationally active in the 1950s and ’60s was brought together by Galería Juana de Aizpuru to mark the 50th anniversary of the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español in Cuenca, where these works were all collected, and which is known as “the cradle of Spanish abstract art.”3 Abstraction came late to Spain, and was rejected by the totalitarian Franco regime and mainstream society as cryptic and subversive.4 Making abstract work was a symbol of resistance to totalitarian values, and Zóbel, the wealthy artist/collector who founded the museum in Cuenca, made sure his generation’s principles would not be forgotten.

Meanwhile, exhibitions by Spanish artists Elena Bajo at Garcia Galería and Santiago Morilla at Galería Fernando Pradilla tackled local and global environmental issues. Pradilla planted hundreds of trees in the forests around Madrid, documenting his intervention with drone-captured video and colorful illustrations of imagined landscapes, while Bajo delved into the politics of capitalist consumption and the rubber and plastics industries destroying the planet. Her narrative video, titled The Land is a Mirror of the Stars (2016), splices footage from rubber plantations and factories with CGI animations, and is supported by a series of minimal sculptures and wall works containing compressed plastic.

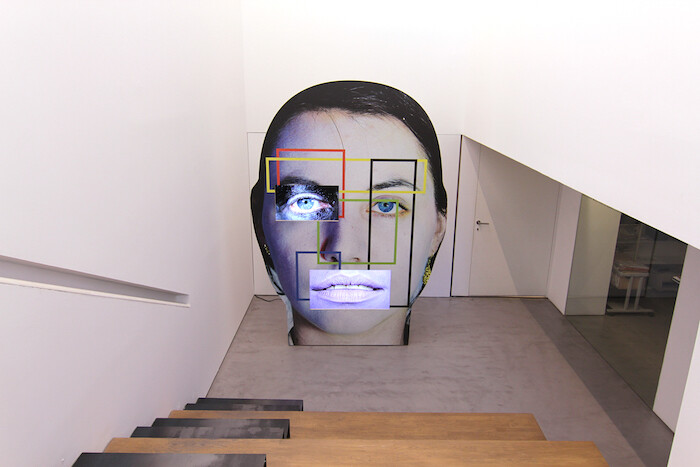

The most magnetic show by far is Tony Oursler’s “A*gR_3,” which presents a new series of works at Galería Moisés Pérez De Albéniz that analyze facial recognition software used for measuring biometric data such as facial scans, iris patterns, and fingerprints. Hyper-saturated videos of human facial features play on smart screens and iPads from behind eye- and mouth-shaped cutouts in mounted C-prints or lacquered aluminum plates that model human heads. Eyes blink and shift out of sequence as distressed voices emanating from the works whisper under their breath, as if trapped inside their casing. The hybrid faces are equally familiar and unnerving, piercing contemporary anxieties about privacy, surveillance, and identity.

Though the Madrid art scene is relatively small, it looks outwards for inspiration, trying hard to keep up with international tastes. At the end of the day, however, it’s the homebrew that’s truly most satisfying, and the local eagerness to focus energy on artistic programming and broadening art audiences is a promising one. The grass may look greener on the other side, but when there’s a dry spell, it’s best to nourish and cultivate your own seed.

Stephen Burgen, “Growth up, joblessness falling – is Spain’s crisis finally over?,” The Guardian, March 26, 2015, www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/26/bank-of-spain-economic-recovery-accelerating.

“Which International Art Fairs Have The Highest Attendance?,” ARTnews, February 28, 2015, www.artnews.com/2015/02/28/which-international-art-fairs-have-the-largest-attendance/.

Andrew Ferren, “Modern Art Amid Ancient Stone in Cuenca, Spain,” The New York Times, January 28, 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/01/30/travel/30overnighter-cuenca.html.

Javier Maderuelo, Catalog Museo de Arte Abstracto Español, Cuenca (Fundación Juan March: Madrid, 2016).