This year’s Bergen Triennial is a mix of carnival, dry reflection, and the reshuffling of archives. The first Bergen Assembly, held in 2013, was preceded by several years of seminars and panels aimed at thoroughly understanding and researching its format. The highlight of this research period was The Biennial Reader (2010), which remains a bible of sorts for the topic. Yet the triennial was, in a sense, too well researched, because “Monday Begins on Saturday” addressed a professional art crowd rather than the local scene. Curated by Ekaterina Degot and David Riff, it was based on a Russian science fiction novel of the same name by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky and attempted to render the book’s ideas about science and research into the triennial’s different venues, which had such titles as “Institute of…

The Bergen Assembly stands out among international contemporary art exhibitions as a perennial triennial, with this edition fragmented over a six-month period and between three unrelated curatorial propositions from Praxes, freethought, and artist Tarek Atoui.1 Between the first and the fourth of September, at approximately the triennial’s midterm, a cluster of events (part of the “September programme, running from 1 September to 1 October) was offered as an occasion for the press to visit. As a transient visitor to the city of Bergen, I felt sometimes short-sighted, sometimes long-sighted, as I constantly had to adjust my vision to different time frames, keeping in mind both the past and future art events, presently invisible.

…This year’s Bergen Triennial is a mix of carnival, dry reflection, and the reshuffling of archives. The first Bergen Assembly, held in 2013, was preceded by several years of seminars and panels aimed at thoroughly understanding and researching its format. The highlight of this research period was The Biennial Reader (2010), which remains a bible of sorts for the topic. Yet the triennial was, in a sense, too well researched, because “Monday Begins on Saturday” addressed a professional art crowd rather than the local scene. Curated by Ekaterina Degot and David Riff, it was based on a Russian science fiction novel of the same name by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky and attempted to render the book’s ideas about science and research into the triennial’s different venues, which had such titles as “Institute of Love and the Lack Thereof” or “Institute of Lyrical Sociology,” with the artists figured as researchers. It was intriguing and the eccentricity of the curatorial blueprint deserved more credit than it received.

This time the public research side of the Triennial consists of talks and panel discussions, most of them arranged by the curatorial collective freethought—the consequence being that it often felt less like a triennial than a seminar on art and cultural theory. I caught myself missing the Russian sci-fi, though for a short while I got something like it from Marvin Gaye Chetwynd’s performance, organized by curatorial group Praxes. The Cell Group (Episode two) (2016) led me into an underground garage with a motley crew of Chewbacca-clones, a baking (grand)mother flanked by a birdman à la Jan Švankmajer, and other weird personages. This theatrical madness, something between a concert, a party, and a parade, worked well as a counterpoint to the dry academicism of the rest of the shows, and also connected with the past in a site-specific manner: although not mentioned explicitly, the performance harked back to the netherworld visited by the Danish-Norwegian playwright Ludvig Holberg in his Niels Klim’s Underground Travels (1741), also played out inside a cave in the hillsides surrounding Bergen. But while Holberg discusses the present in a satirical mode reminiscent of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), Chetwynd’s drama was more of a carnivalesque release valve than an exercise in utopian thinking.

This burrowing brought to mind the diggings performed by freethought at Hagerupgården: attempts to mine the past’s utopian potential through documentation. One room is dedicated to the history of the group that formed around London’s Partisan Coffee House, which eventually led to the founding of the magazine New Left Review in 1960. Tickets from concerts, photographs, letters, and other memorabilia bring to life the discussions between important thinkers and writers—Stuart Hall, John Berger, and Raymond Williams among them—who learned their art, and even had their offices, here. In another room the cosmopolitan reach of the Shiraz Festival in Persepolis in Iran (which lasted from 1967 to 1977) is made visible through images, video, brochures, catalogs, and posters. Iannis Xanakis and John Cage are presented in the same setting as Persian folk musicians and Japanese actors. These spatial essays on transformative moments from the past remind us of how archaeological explorations of history are closely allied with an understanding of the present. It would have been interesting to see these documentary, essayistic sparks more evenly distributed at the triennial.

In Tarek Atouis’s Infinite Ear (2016), Sentralbadet, Bergen’s old public pool, has been transformed into a laboratory for experimenting with sound and instruments for the deaf and hearing impaired. The idea of sound as an exclusively audible medium is so thoroughly ingrained that the invention of music for deaf people seems incomprehensible to most. Atoui shows that it is possible—through vibrations, primarily. This synesthesia in practice generously confirms the interconnectedness of the senses and considers how sound, as such, has to be rethought and retaught in order to be fully understood and appreciated.

I longed for an overarching theme at this year’s triennial, something that connected its different parts, or a question researched and explored through the production and exhibition of art. The decline of the Norwegian oil industry and the importance of finding other sources of work and revenue is touchingly documented in the film Oilers (2016) by freethought’s Massimiliano (Mao) Mollona and Anne Marthe Dyvi, but a real discussion of post-oil Norway never really appears. Phil Collins’s short anime-film Delete Beach (2016) also revolves around the collapse of the oil industry, even if an elliptical and cryptic manner. The story of the world the artist tries to describe—a dystopian future Bergen—is too ambitious for the few minutes the work lasts.

There is a tidy presentation of Lynda Benglis’s work in the group show “Adhesive Products” at Bergen Kunsthall. Praxes, which organized this and several other Benglis shows, contextualizes the artist’s practice well through other artists working with abject materiality in sculpture. The excesses and vulnerabilities of the body that surface in Benglis’s works are set next to the rust processes that undermine the sculptural pieces by Olga Balema, for instance. It is a solid curatorial project, but it remains hard to tell how Benglis connects with other parts of the triennial.

While freethought’s seminars and panels are of interest to art professionals—Elizabeth Povinelli’s talk on what escapes infrastructures, part of a two-day discursive event titled “The Infrastructure Summit,” and Tiziana Terranova’s ideas about social media as a tool for thinking, for example, were stimulating—the lack of genuinely striking new art that might appeal to a local audience was disappointing. The Assembly recalls the practice of the ethnographer in Tom McCarthy’s novel, Satin Island (2015), discussed in a conversation between McCarthy and Mollona part of freethought’s program. The character’s “Present-Tense Anthropology” prevents him from observing an object without theorizing it: experience is about inventing a theoretical narrative about the world as you go. But sometimes not thinking too much—which stiffens the perceptions and stilts the capacity to be struck by something—is a way of preserving thinking.

The Bergen Assembly stands out among international contemporary art exhibitions as a perennial triennial, with this edition fragmented over a six-month period and between three unrelated curatorial propositions from Praxes, freethought, and artist Tarek Atoui.1 Between the first and the fourth of September, at approximately the triennial’s midterm, a cluster of events (part of the “September programme, running from 1 September to 1 October) was offered as an occasion for the press to visit. As a transient visitor to the city of Bergen, I felt sometimes short-sighted, sometimes long-sighted, as I constantly had to adjust my vision to different time frames, keeping in mind both the past and future art events, presently invisible.

Praxes was initiated by curators Rhea Dall and Kristine Siegel in Berlin in 2013 as a series of long-term parallel investigations into the work of two unassociated artists (such as Judith Hopf and Falke Pisano in 2014, and Christina Mackie and Matt Mullican in 2015) whose results take various public forms over the course of a half-year cycle. Praxes has maintained that specific structure for the Bergen Assembly, exploring the practices of Lynda Benglis and Marvin Gaye Chetwynd. Early September synchronized the end of the exhibition “On Screen” at the nonprofit gallery Entrée, which showed three of Benglis’s video works from the early 1970s, with the opening of “Adhesive Products,” a group exhibition at Bergen Kunsthall of younger artists (Nairy Baghramian, Olga Balema, Daiga Grantina, Sterling Ruby, and Kaari Upson) in conversation with Benglis’s work. Named after Benglis’s iconic polyurethane pouring installation of 1971, the latter exhibition focuses on the artist’s foam spills, dwelling on the term “frozen gesture,” coined by Robert Pincus-Witten in a 1974 essay about her work in Artforum.2

The two exhibitions interestingly echo the issues at stake for Benglis during that period: Benglis’s Female Sensibility (1973), an ambiguous video that plays with the notion of the male gaze, features the artist making out with a woman while looking surreptitiously at the camera, while Kaari Upson’s Black Hole (2015), a polyurethane pleat that hangs suggestively off the wall, is potentially reminiscent of Robert Morris’s felt pieces, which Pincus-Witten evoked in his essay as a way to contextualize the sexual content of Benglis’s work among her (mostly male) peers.

In the context of her prolific and exuberant practice, Chetwynd’s exhibitions and performances come off as curious pieces of an never-ending puzzle, where features nevertheless surface. The exhibition “Are U Bats?” presents her ongoing series of “Bat Opera” paintings on a funky rockery wall at the entrance of a city hall building; “Cocaine & Caviar,” at Kunstagarasjen, samples her major performances from the past ten years accompanied by a display of props and costumes. A new commission for this edition of the triennial, The Cell Group (Episode 2) (2016), performed during my stay, appeared partial, but the artist announced at the end that it was a rehearsal; further investigation seemed like a task for dedicated admirers.

freethought’s proposition for Bergen is complex and profuse: Irit Rogoff, Stefano Harney, Adrian Heathfield, Massimiliano (Mao) Mollona, Louis Moreno, and Nora Sternfeld are carrying out a two-year research project that considers how infrastructure—the “most invisible of governing entities,” according to a flyer distributed at the exhibition—shapes the world. The project positions research as “a way of living a reflexive life aware of its conditions,” broadening research’s reach outside the realm of academics, and reflecting on what it means to display knowledge in art spaces. Several threads cohabit a complex structure of exhibitions, screenings, and live events, culminating with “The Infrastructure Summit,” two days of presentations and discussions.

The title of “Shipping and the Shipped,” the exhibition curated by Stefano Harney, refers to the sixth chapter of the book he co-wrote with Fred Moten, The Undercommons (2013), which focuses on the advent of logistics with the Atlantic slave trade.3 Some works reveal the dialogues and friendship between artists and philosophers: Arjuna Neuman with Denise Ferreira Da Silva and Wu Tsang with Fred Moten. The last floor of the building houses “Assembled Archives,” curated by Irit Rogoff, which presents a variety of archival materials on the Shiraz Arts Festival held in Persepolis from 1967 to 1977, exemplary in its avant-garde format; the Partisan Coffee House, a venue opened and operated by the New Left in London; transcripts of former freethought discussions held in Bergen; and a multi-screen installation of filmed interviews with curators, artists, and researchers about the meaning of an exhibition. So much content is compiled in the space that it defies one’s cognitive capacities, negating the body of the viewer. It traps the viewer in a strange tautology, where one must navigate the coercive web of logistics the project purports to address, exemplifying the aporia of archival displays: caring for the conditions of the viewer is important for implementing critique.

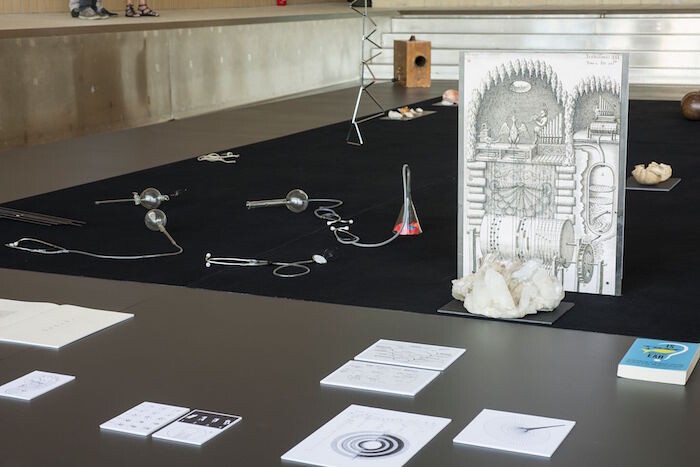

Tarek Atoui’s Within, a long-term project initiated in 2008 in the context of his residency at the Sharjah Art Foundation, aims to explore how deafness can expand the notion of hearing and thus reconfigure sound performance. For the iteration of Within in Bergen, the artist developed nine new instruments that explore aspects of sound beyond the aural. To accompany these instruments, Atoui invited curatorial office Council (Grégory Castéra and Sandra Terdjman) to organize an exhibition and various programs called “Infinite Ear,” based on their parallel research project into deaf people’s perception of sound and alternatives to phonocentric natural histories of hearing. Both projects take place at Sentralbadet, a closed public swimming pool in downtown Bergen, which provides specific acoustics and affects, as many locals remember bathing there as children. In “Infinite Ear” dormant objects retrace the research undertaken and wait to be activated, just as the instruments require activation by musicians. For the launch, Atoui invited Pauline Oliveros, Mats Lindström, Espen Sommer Eide, BIT20, and other guests to perform three sessions with these new instruments. BIT20 performed a composition by Oliveros, a pioneering electronic music composer, under the direction of a deaf conductor, which closed the event. It was a matter of perspective: knowing that the complex and subtle composition of the music could be perceived by those who don’t hear was an expanding experience for those who do. At the same time, it was very moving to observe the separation between the world of hearing and the non-hearing being breached.

Bergen Assembly’s temporal format is distinct, risking imprecision. As in musical improvisation, it brings the viewer to a place where the flaws are more visible but also where true experiment is possible and where extraordinary moments are also potentially visible. The event comes across as various efforts to bridge separate entities and to get a little closer to a “difference without separability”—to quote Moten quoting Denise Ferreira Da Silva during “The Infrastructure Summit”—an expression that keeps coming up like the tide.

Bergen Assembly describes itself as “a perennial model for artistic production and research that is structured around public events taking place in the city of Bergen every three years.”

Robert Pincus-Witten, “Lynda Benglis: the Frozen Gesture,” Artforum (November 1974): 54–59.

Stefano Harvey and Fred Moten, “Fantasy and the Hold,” in The Undercommons:Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Wivenhoe: Minor Compositions, 2013), 84–99.