Berlin affluence is an oxymoron that might describe something in the big gap between pilsner and champagne, or pork schnitzel and sous-vide. Events like Berlin Art Week and its commercial fair abc art berlin contemporary have been pushing the German capital onto the national and international buyers’ tour for nine years now. It remains an odd positioning, as Berlin isn’t an obviously digestible city for many collectors; it lacks their creature comforts: the ubiquity of restricted access and unaffordable prices with enough locals who can afford to keep them that way. And art fairs (not to be confused with life) are most successful—and most distracting—when the rich feel hungry and foot the bill for the entertainment. But it’s an important exercise to distinguish between wealth and security (not to be confused with fear). The former is an uncertain orgasm of contrasts, which has become aesthetic cliché, while the latter is more interesting and maybe even radical today. Without the pressure (and pleasure) of fast and fat capital in recent history, Berlin has profited from this advantage, and although events like abc might be experimenting to revise that, the city still remains at one remove, which is a privilege, because the potential for alternative ways of life is higher. With this in mind, I had a look around the exhibitions and events leading up to and around Berlin Art Week.

Jos de Gruyter & Harald Thys, “Pantelleria,” Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie

I have a book called Fine Arts (2005) by the Belgian artist duo Jos de Gruyter and Harold Thys. There’s no text, and I page through it when I don’t want to think. Its series of unrefined watercolor paintings of everyday life in the past are funny and perverse, simple and even. Their matter-of-fact titles—Victorian Bedroom, Ruins of the Roman Empire, A Beautiful Lady—are a reminder that describing life can be more satisfying than interpreting it.

De Gruyter and Thys’s exhibition “Pantelleria” at Bortolozzi was my first this September in Berlin. The title is also the name of an volcanic island in the Strait of Sicily where A Bigger Splash (2015), by Italian filmmaker Luca Guadagnino, was filmed. A promotional image for the show was a modernist sun that suggested a clock, a good pairing for the end of the summer. The show itself was nothing like the Mediterranean, although there are paintings of beach balls and rain umbrellas that might be used in the sun, both subjects depicted with a stark white background, isolated so as to make them look ready for online shopping. Appropriate again, because of course living in Germany makes spending time in the sun something of a supply-chain thing: we travel to get it, and therefore tolerate the traps of tourism and dodge the long-term economic strains that come with living in those southern places we travel to. One work, Compass White Element (2016)—made with the artists’ signature steel, fabricated to look like paperboard—points north.

Northern burnout comes to mind in de Gruyter and Thys’s work. White steel structures double as cutout figures, with deadpan portraits of white Europeans delicately hung on the hard metal. In their video Die Aap van Bloemfontein [The Ape from Bloemfontein] (2014), amateur models with bad haircuts stand in silence, dressed so normal that it freaks me out. A voiceover narrates this film of worried-looking actors, who seem to be lying in state even when upright. The camera zooms in on their sweaty skin, which has the unattractive consistency of boiled milk fat. The narrator talks about appendicitis and getting glasses of water and oranges and bananas speaking to each other. Once again meaning is flattened, and you can’t distinguish between hydration and insanity. Like indigestion, or Belgian humor, it all makes me feel uncomfortable.

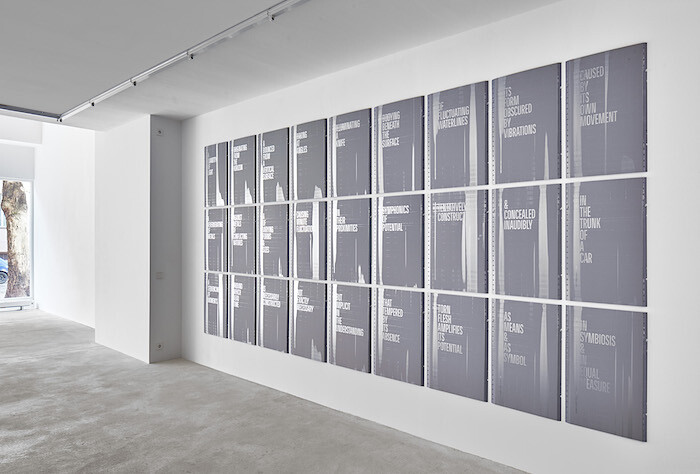

Studio for Propositional Cinema, “(To the Spectator:),” Tanya Leighton

Also eerie, though more beautiful and not funny at all, was the opening of Studio for Propositional Cinema’s “(To the Spectator:)” at Tanya Leighton the following night. SPC is a conceptual group effort and therefore consists of an intentionally confusing set of strategies. I arrived late, and it appeared that the exhibition was closed, but everyone was still hanging out. It turns out there are no lights in the show. Natural light and darkness as a gimmick gives visitors the added, and rare, possibility to feel connected: to nature, to cycles bigger than ourselves and our fears and our agendas. In the dark, I could make out stenciled texts above doorways in the gallery. Struggling, I read one: “BEING OBSERVED / SHE TURNS HERSELF INTO AN IMAGE / FOR HIM BUT FROM WHICH HE IS CROPPED.” Like this poetry, supposedly written by SPD, there’s something ambivalent about reading in the dark. It’s at once a private indulgence, like looking for food in the fridge in the middle of the night, and, when public, it’s also a small outcry, demonstrating a kind of angst to know, like a Bildungsroman. I went back the following Saturday to see the works in unusually hot sunlight. In addition to the stencils, there’s fragile and sentimental poetic text printed on different metals and foils. The combination of self-evasiveness and somatic violence is very complicated and difficult to understand: “THEY ARE ABSORBED ONLY LONG ENOUGH TO SUGGEST WHAT COULD HAVE BEEN & REMEMBERED ONLY INSOFAR AS THEY SUGGEST WHAT STILL COULD COME: A LENS AS A CONDUIT CONSTRUCTED TO BE FOGGED A SKIN AS A PRECIPICE DESIGNED TO BE FLAYED).”

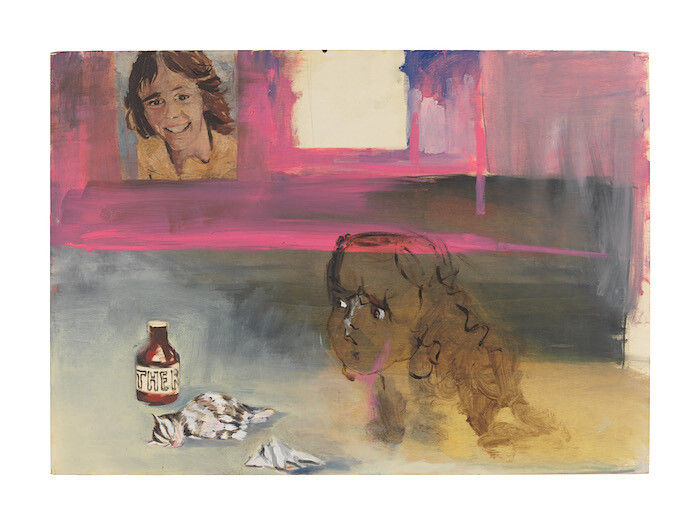

Georgia Gardner Gray, Schaumstoff Laden, ACUD gallery

The next day I went to the opening of American artist Georgia Gardner Gray’s play Schaumstoff Laden at ACUD in Mitte, where she also showed new paintings and sculptures. Gray’s paintings are fucked up: brightly colored and dark-themed rococo renditions of togetherness today, they’re like expired fêtes galantes basking in bleeding mascara. One small painting, Car Crash (2016), is a deadly depiction, while the characters in the other pictures seem to care less about such events, even if they’re happening right in front of their eyes, which peer not at you but in your general direction. Whether accidental or self-inflicted, catastrophe is everywhere, and repression and bliss are the only tools we have to cope.

Schaumstoff Laden starred all guys—fellow artists and friends living in Berlin—who acted out Gray’s queer disco fantasy. I knew it would be the funniest thing I’d see during Berlin Art Week, and it was. Schaumstoff means foam in German, and the play takes place at the Schaumstoff Laden, a place to get foam, soft little pieces of bedding sold to customers who each want to momentarily forget about something—a crying baby, a thankless job, or a raging libido with no one to share it with. The main character is the sex icon Penny, an outsider in the world but a superstar in the world she created for herself. Without a single spoken line, Penny speaks for a lot of us.

Amelie von Wulffen, “Der Tote im Sumpf,” Barbara Weiss Galerie

The next week I popped into German artist Amelie von Wulffen’s show at Barbara Weiss, titled “Der Tote im Sumpf,” which in English means “the dead in the swamp.” The way von Wulffen renders both domestic rituals and psychotic demons in her oil paintings is original and masterful, and her love for the medium is matched by her ability to create weird and historic scenarios with it. In these untitled works, little girls poison cats, Paul Celan lurks above a crying Bavarian boy, and elderly Germans oblige broken stoicism. Somewhere between the silence of understanding and the admission of deceit, there is painting. It must also be noted that Berlin is built on a Sumpf.

Anne Imhof, Angst II, Hamburger Bahnhof — Museum für Gegenwart

Later that evening, at the Hamburger Bahnhof, German artist Anne Imhoff and her friends and amateur and professional actors were performing Angst II, the second installment of her three-part “opera-exhibition” (the first was presented at Kunsthalle Basel this summer). Angst has been trending hard but it’s bewitching, and its fashion is so spot-on that it’s hard to differentiate the audience from the performers. The participants slowly enact scenarios and tasks as if building tableaux. It’s all very behind-the-scenes, black-and-white cinematic: smoke machines, sodium lighting, and a live minimal soundtrack. A slackliner passes along the upper part of the central atrium of the old train-station venue, as do drones and a falcon. Groups of characters illustrate on walls; they smoke, shave, weigh items on small drug scales, and appear both at ease and determined (Imhof’s opera references the word’s original meaning: “work” or “care”). The title Angst makes sense for any reasonable worldview today, but Imhof’s artwork itself communicates grace and style in acceptance, and originality and resolve in mundane actions; in a lot of ways, Angst is a safe space. Taking place from 8:00 pm to midnight, it’s also a late-night pleasure happening, adding to the Berlin ritual that other cities can be envious of.