Almost a year ago, when chief curator Jochen Volz announced his proposal for the 32nd edition of the Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil was already undergoing a severe political crisis, with the country split between those who supported the democratically elected coalition government and those who called for the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff. Titled “Incerteza Viva” [Live Uncertainty], the exhibition opened to the public only a few days after Rousseff was permanently ousted from office in a controversial trial based on corruption charges that paradoxically ensured that political sectors known to be corrupt remain in power. In his inauguration speech, unelected president Michel Temer stated that uncertainty had finally ended, but the demonstrations that have been taking place almost daily across the country since Rousseff’s impeachment seem to point to the contrary. During the biennial’s preview, a group of artists wearing black t-shirts with slogans from the late dictatorship days— such as Eu quero votar pra presidente [I want to vote for president] from the Diretas Já [Elections Now] campaign, and the more up-to-date Fora Temer [Out Temer]—took to the Oscar Niemeyer pavilion that hosts the exhibition. Apart from a few scuffles with members of the public, the protest was mainly peaceful—street demonstrators have recently been severely repressed by São Paulo’s military police.

But Brazil’s political turmoil is only one among the many big questions of our time that the team of curators of “Incerteza Viva”—Volz, Gabi Ngcobo, Júlia Rebouças, Lars Bang Larsen, and Sofía Olascoaga—have brought to the table for this edition of the biennial. Rather than focusing on a specific event, the exhibition addresses uncertainty as a contemporary condition brought on by global warming; loss of biological and cultural diversity; economic and political instability; global migration; and the dissemination of xenophobia, among other destabilizing factors whose effects on the future of the human species remain unknown. These may seem like too many topics to take on in a single exhibition, but in spite of the grim prospects suggested by this long list of human-led disasters, the curators claim that uncertainty should be dissociated from fear and that art’s rebellious imagination feeds on uncertainty. Indeed, most of the work by the 81 artists and collectives featured in this Bienal is less accusatory and more propositional, often incorporating or praising indigenous and vernacular forms of knowledge that may offer an alternative to the destructive logic of late capitalism.

“Incerteza Viva” is an exhibition that eschews monumentality and avoids the usual international art stars; more than half of its participants are women. At the main entrance to Niemeyer’s pavilion, visitors encounter a large group of sculptures made with burnt wood from illegal forest fires by 95-year-old Frans Krajcberg, a Polish émigré who settled in Brazil in the late 1940s. Although fairly well-known in the country, the artist has largely remained beneath the international circuit’s radar, and his “forest” of burnt trees, formed by three groups of sculptures, “Gordinhos” [Fatties], “Bailarinas” [Ballerinas], and “Coqueiros” [Palm Trees], functions both as an indoor extension of the park that surrounds the building and a prelude to a biennial in which organic forms and ecological concerns recur. Next to Krajcberg’s installation, the subject is reinforced by Bené Fonteles’s Ágora: OcaTaperaTerreiro (2016), a large adobe construction that resembles the rounded dwellings built by indigenous Brazilian peoples and filled with altar-like assemblages of vernacular objects and photographs of scientists, political and spiritual leaders, and artists. The agora doubles as a gathering space that will host a series of conversations with the artist—who has also been an environmental activist since the 1970s—in order to “postpone the end of the world.”

Some of the works on the ground floor speak less directly of ecology while still implying the need to reconnect with nature’s cycles in the age of the Anthropocene. This is the case in Jonathas de Andrade’s new film O Peixe [The Fish] (2016), an engrossing and beautifully shot fable of fishermen who embrace their prey after capture, creating an imagined ritual of empathy between humans and beasts; or in Ruth Ewan’s Back to the Fields (2015-16), an installation where the artist has brought to life the French Revolutionary Calendar—based on seasonal changes—through a collection of more than 300 plants, minerals, and objects traditionally associated with each month of the year.

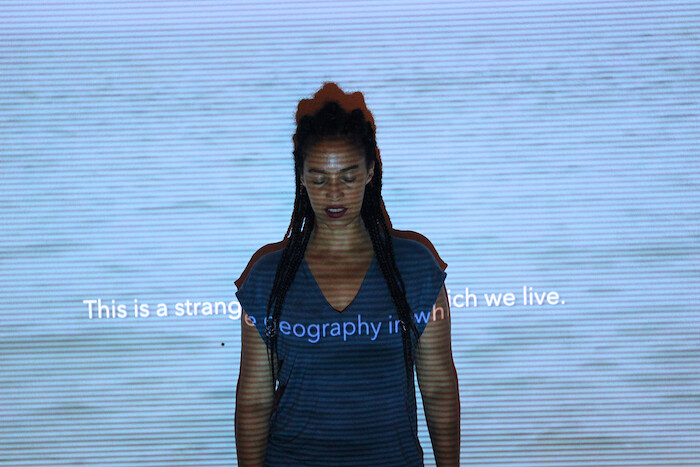

Further along the pavilion, the trilogy of short films Cantos de Trabalho [Work Songs] (1975-6) by filmmaker Leon Hirszman documents the fading tradition of work songs among rural communities in northeast Brazil, a simple yet powerful reminder of the importance of a shared culture as a means of resistance. Music is also at the center of some of the most engaging works in this biennial, such as Bárbara Wagner’s poignant film Mestres de Cerimônia [Masters of Ceremony] (2016), featuring the brega and funk communities in the north of the country and showing how young MCs and dancers use the codes and choreographies of these genres to empower themselves. This pop sensibility resonates in Cecilia Bengolea and Jeremy Deller’s utterly hysterical film Bombom’s Dream (2016), a frantic music video-style documentation of twerking dancehall moves in Jamaica, or in Vivian Caccuri’s installation TabomBass (2016), a large stack of ultra-bass sound systems built only with sub-woofers that periodically plays tunes composed by musicians from Africa and Brazil, emitted in such a low pitch that sound waves can be felt across the visitor’s body. The rhythmic beat is also a prominent feature of Grada Kilomba’s moving installation The Desire Project (2015-16), which comprises three videos showing different texts written by the artist against a black background. Born in Lisbon and of African descent, in this piece Kilomba combines writing and sound in an attempt to undo colonial constructions of the self while investing text with a performative quality.

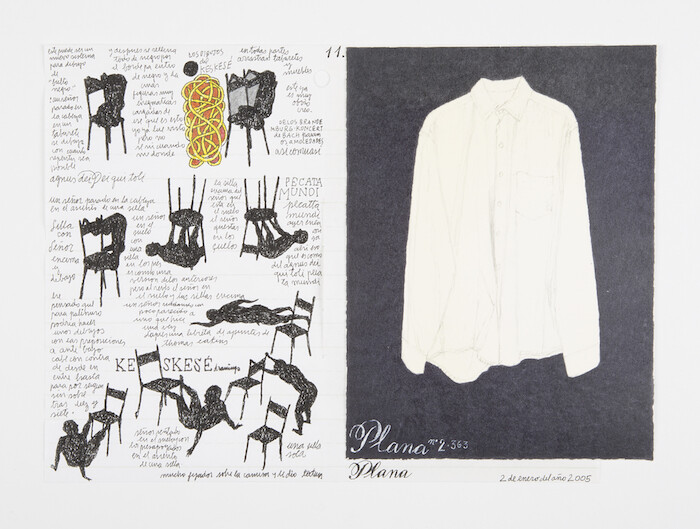

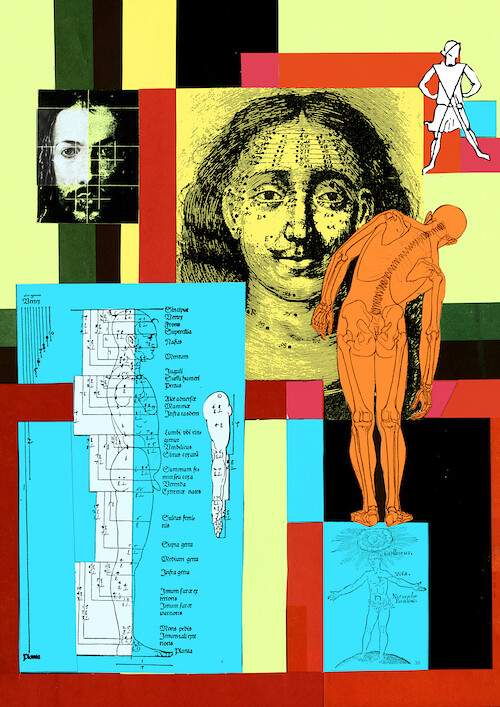

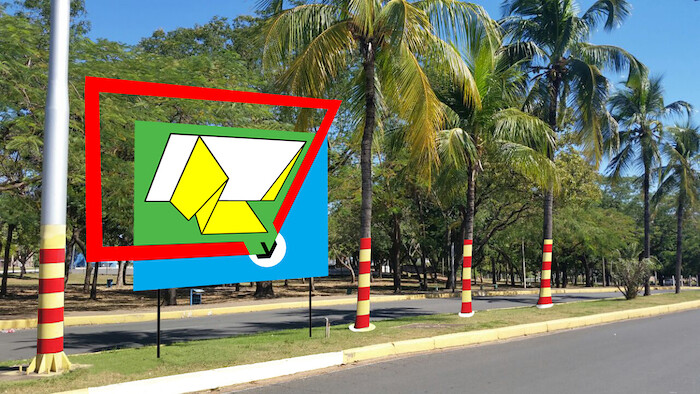

But beyond the immateriality of sound and video, “Incerteza Viva” offers plenty of works with a strong physical presence, with earthly hues predominating across the three floors of the exhibition. From the dark pressed soil, the cavities of which are filled with ceramic objects, gold leaves, and petals in Dineo Seshee Bopape’s floor installation :indeed it may very well be the ____itself (2016), to Erika Verzutti’s massive semi-abstract papier-mâché panels or Rita Ponce de León’s interactive adobe structure En forma de nosostros [In the Shape of Us] (2016) where visitors can accommodate their body parts, earth (or the allusion to it) seems to appear equally as a call for reengagement with the planet’s resources and as an index of the prominent role that tangible artworks play in this edition of the biennial. This is an exhibition that privileges the visual over the documental or textual, but it does so without resorting to blockbuster tactics. On the contrary, there are several examples of modest yet powerful collections of works that have been obsessively developed by artists over extended periods. Examples of these include Antonio Malta Campos’s unpretentious works on paper titled Misturinhas [Little Mixtures] (2000-16), José Antonio Suárez Londoño’s vertiginous collections of drawings from the series “Exercises: from January 1 to December 31 of the year 2005” (2005), Sonia Andrade’s Hydragrammas (1978-1993), an inventory of more than one hundred everyday objects forming a subjective alphabet, and Wlademir Dias-Pino’s Enciclopédia Visual Brasileira [Visual Brazilian Encyclopedia] (1970-2016), comprising hundreds of images that have been collected and classified by the artist over a period of more than 40 years.

“Incerteza Viva” is a polyphonic exhibition that is generous enough to foreground the art in detriment of grand curatorial gestures. While some visitors may complain about the lack of stereotypical biennial-style grandiosity, the curators’ down-to-earth approach has ensured that consistency and quality are maintained throughout the exhibition. For the first time in the history of the Bienal de São Paulo, all visitors’ facilities—such as cloakrooms and information desks—have been placed outside the pavilion and security checks have been eliminated, creating a seamless connection between Ibirapuera Park and the exhibition. This simple yet invisible curatorial strategy has already translated into more than 60,000 visitors in the opening week, proving that a biennial doesn’t have to be populist to be popular. Not that figures are necessarily a sign of excellence, but in a country where the Bienal de São Paulo remains the main platform for contemporary art, increasing access beyond the international art world that attends the preview week or the programmed school groups is an important move towards the democratization of culture. This is particularly relevant in the current political moment, when government policies are clearly taking a conservative turn. Without being overtly militant or nostalgic, “Incerteza Viva” presents a consistent selection of works that take uncertainty as a productive force that can generate new ways of being in the world, and their clues can be especially valuable to a country in need of urgent political reinvention.