Contemporary biennials are never simply showcases for new work: they bear the weight of meta-commentary. As they struggle to articulate the conditions of their own production and reception, they become lightning rods for debates, not least those concerning art world complicity with, or resistance to, globalization. The networks and flows of art world capital, particularly in relation to sponsorship, have been subject to critique and protest: witness the Sydney and São Paulo biennials of 2014. Meanwhile, artists and commentators continue to police issues of representation: numbers of local artists versus national and international, and continuing gender and racial biases.

The TarraWarra Biennial, founded in 2006, circumvents some of these debates by committing itself to Australian content. The TarraWarra Museum of Art, nestled into Yarra Valley wine country an hour and a half outside of Melbourne, is humble in scale, which means that the works talk to each other and energy isn’t dissipated between venues. It also means, unfortunately, that the show is inaccessible to many Melbournians. For an exhibition proposing circulation as its central motif, it sits far outside the circulatory system of the city.

Nevertheless, the biennial makes clear links back to Melbourne with its selection of artists, which cynics might label a roll call of the usual suspects. A more generous reading would be that the curators are committed to supporting local talent with a long view towards sustainable careers, rather than short-term goals of taste-making.(1) This isn’t, as Andrew Berardini puts it in his recent review of “Made in LA,” “a trend report for outsiders,” but rather the “look in the mirror” characteristic of localist biennials.(2)

Putting a mirror to twenty-first-century Australia means staring colonization and its discontents hard in the face. Much of the work on show is indigenous and politicized (somewhat surprisingly, none of the indigenous artists are women, although indigenous women have been a significant feature of recent TarraWarra programming). Vernon Ah Kee and Robert Andrew both use text to make their points, yet both perturb an easy reading. Ah Kee’s authorsofdevastation (2016) runs red words together on a black ground: as you struggle to make out sentences, the penny drops that the fleeting discomfort you experience is a mere microcosm of what it feels like to be culturally dispossessed. In Andrew’s Transitional Text – BURU (2016) a singular word in red ochre reveals itself over time: Buru, land, emerges as the painting’s ground as a stream of water gradually breaks down a surface layer of whitewash.

Wukun Wanambi’s paean to continuity, Nhina, Nhäma, Ga Ngäma (Sit, Look, And Listen) (2014), is a single-channel video work in which the artist and elder has meshed footage, taken over many years, of the ceremonies of his community. Wanambi divides the screen vertically into six “poles,” reminiscent of decorated memorial poles commemorating those passed, combining film and video of differing qualities and time signatures. Abutted, the thin strips concatenate time, affording a glimpse of a history stretching back thousands of generations. The soundtrack of song and clapsticks holds myriad scenes of bodies, adornment, and movement in a space beyond time. When the images fade, the sound remains, leaving the viewer in a blackness that is not void but full, replete.

Other video works enact connection across time and space; Eugenia Raskoupolous’ Rootreroot (2016) figures a north/south divide. Above, an olive branch sweeps a perfect clockwise circle into soil; below, the same arm sweeps a native Australian wattle branch counter-clockwise. The aerial perspectives (shot with drones) turn the hermetically sealed loops into an infinity symbol. Similarly, the disconnected halves of Bianca Hester’s two-channel video Constellating bodies in temporary correspondence (2015-16) momentarily coalesce, only to collapse and disperse. Constellating bodies documents a loose collective of people carrying thin bronze rods across an ancient lava flow in Auckland. Connecting people into cooperative formations, the roughly chiseled rods are like elements of a Beuysian social sculpture, or a deconstructed version of Walter de Maria’s The Lightning Field (1977), possessed of a unifying, magnetic quality.

Art production in “Endless Circulation” is envisaged as the fulcrum in a Möbius strip—the point at which north and south, individual and collective, inside and outside fold into one another in a mutually constitutive dance. Masato Takasaka stands out for looking inwards, positing practice as self-parasitism, with an installation made of reconstituted elements of the artist’s own back catalog (ANOTHER PROPOSITIONAL MODEL FOR THE EVERYTHING ALWAYS ALREADYMADE WANNABE STUDIO MASATOTECTURES MUSEUM OF FOUND REFRACTIONS 1994-2016 (r)eternal return to productopia-almost everything all at once, twice three times (in four parts…TWMA BIENNIAL 2016: Endless Circulation remix), 2016). Appropriate to this feedback loop, much of the imagery in Takasaka’s sprawling composition board empire is littered with posters from rock magazines and objects including an effects pedal for an electric guitar, conjuring the endless recursions of reverb.

Contrary to Takasaka’s solipsism, many of the artists engaged broader communities: 3-ply and Centre for Style produced a fashion magazine and a multi-authored clothing collection, while Christopher L G Hill invited yet more Melbourne artists to participate in the “4th/5th Melbourne Artist Facilitated Biennial,” a kind of Biennial-within-a-Biennial (not so much meta- as micro-). Debris Facility, a collective that has “colonized” the artist Dan Bell, infiltrates the museum’s bathrooms with Excipient (2016), their special brand of “activated charcoal” soap. The Facility also utilizes that other exemplary site of circulation, the shop. Bracelets made from hollow plastic tubing are filled with coconut oil, mustard seeds, and a smattering of glitter (The Facility advocates for the original, magical meaning of glamor). The heat of a wrist renders the oil transparent and fluid, allowing the mustard seeds to bubble and swim in an endless circle.

The symbolic trajectories of body adornments are a part of the Kula ring, a trade network among the islands of the Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. Kula exchange has fascinated anthropologists from Bronisław Malinowski and Marcel Mauss to Marilyn Strathern, who argues in The Gender of the Gift (1988) that ritualized exchange can separate as much as connect. Newell Harry’s photographic and diaristic encounters with Kula exchange in 2015, (Untitled) Nimoa and Me: Notes from Kiriwina, sees the artist in a very different mood to his usual politically charged installation practice. His engagement with people as well as places and objects makes an interesting counterpoint to the somewhat dry, clinical approach to monetary systems and energy circuits in the materialist practice of Melbourne artist Nicholas Mangan. That Mangan isn’t represented in “Endless Circulation” is surely only because the artist is currently taking part in a survey show at the Monash University Museum of Art, but his extensive work on flows of capital throughout the Pacific, particularly in relation to mining, is a significant springboard to the Biennial’s key themes.(3)

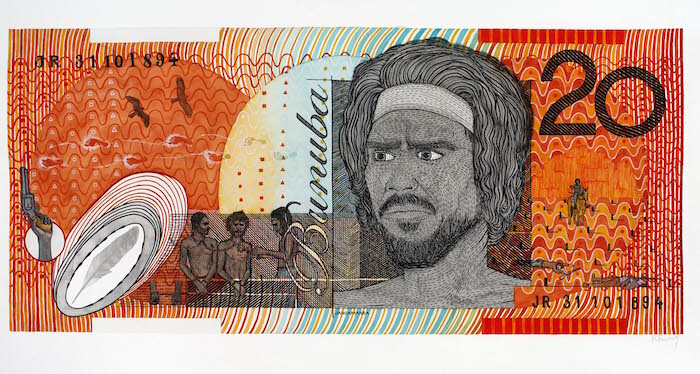

Ryan Presley’s Blood Money (2014) marries the circulation of currency with the pumping (and spilling) of blood. His facsimiles of Australian banknotes featuring Aboriginal, instead of white, heroes can be purchased for their equivalent denomination in Australian dollars. In a new series of small paintings, “Themesong,” the artist has juxtaposed delicately patterned surfaces with warped heraldic devices, from nuclear warheads to honeycomb circled by flies. The cymatic patterns are generated from the sonic vibrations produced by “Advance Australia Fair.” This abstraction of the national anthem reverberates with Takasaka’s guitar pedal via Jimi Hendrix’s psychedelic mutation of “The Star Spangled Banner” at Woodstock in 1969, at the height of the Vietnam War.

The TarraWarra Biennial’s opening week coincided with the Spring 1883 art fair, brilliantly staged over four floors of the Victorian heritage hotel The Windsor. Art amidst flaming carpets and chandeliers was pure eye candy, a guilty pleasure for those professing to critique the machinations of the market. Nevertheless, Spring ended on a surprisingly politicized note: as the bedroom suites closed and the bleary-eyed masses congregated in the foyer, Melbourne artists Kate Daw and Stewart Russell orchestrated the choir from the Victorian College of the Arts Painting Department (where Daw is Head), to sing a somber choral piece in a strange language. It was “Advance Australia Fair” sung as if the score was upside down and back-to-front, sending reverberations out to Presley’s cymatics and Hendrix’s caterwauling protest.(4) All the connotations of “Fair” were raised like specters at a séance—the World Fairs, with their exhibition of peoples as exotic sideshows, fair as whiteness, and as a “level playing field.” That a commercial enterprise like Spring concluded with this gutsy reversal seemed an acknowledgement of unfairness, and in the momentary, perplexing magic of its unfolding, a reminder that not everything is for sale.