June 25–September 24, 2016

Fouad Elkoury’s photographic installations produce in me a swell of desire and mourning for places that I have never directly observed. Since the 1970s, Elkoury has photographed his home country of Lebanon and the surrounding areas of North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe, tracing a geography of places through images of everyday life: scattered café chairs, empty swimming pools, the swell of waves on the Marmara or the Gulf of Aden. They are at once documentary records and ripe metaphors of transience, modernity, empire, and war—a century of cultural cross-fertilization between East and West. These tensions are neatly contained in the show’s title, “Blues for the Orient,” which is borrowed from a 1961 track by the American saxophonist Yusef Lateef. Elkoury toys here with the Orient as both real and imaginary, as a mood in minor scale.

At London’s Rodeo gallery, Elkoury has papered one whole wall in a black-and-white image of an apparently abandoned swimming pool in a densely forested park (Yarze, 1974). Elkoury has set out to generate a feeling, a mood of elegy and luxuriance given by the dense foliage, which the visitor to the gallery can almost step into—but crucially cannot ever fully access. Elkoury’s images work through denial and lack, through a rich and suggestive image paired with a title that hints at information that the viewer may or may not already know. The title Yarze references a village near Beirut, which happens to be the site of the headquarters of the Ministry of Defense and of The Hope for Peace (1995), a bombastic public monument designed by the French artist Arman and formed from dozens of military weapons encased in a tower-block-like chunk of concrete. Elkoury’s works play with the viewer, toying with our level of knowledge, our preconceptions or insights, so that no two visitors will encounter quite the same work.

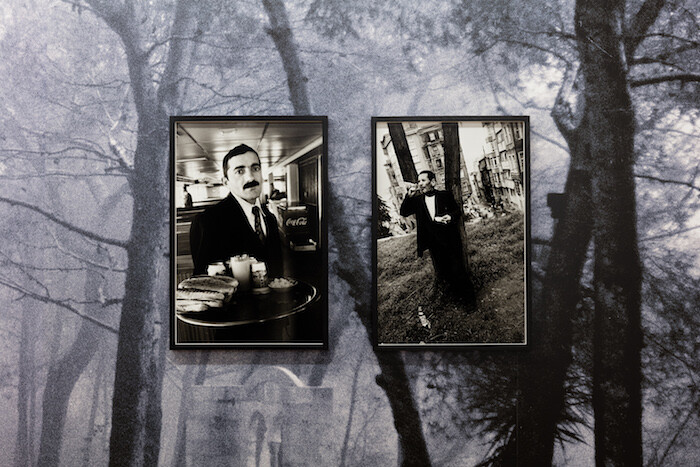

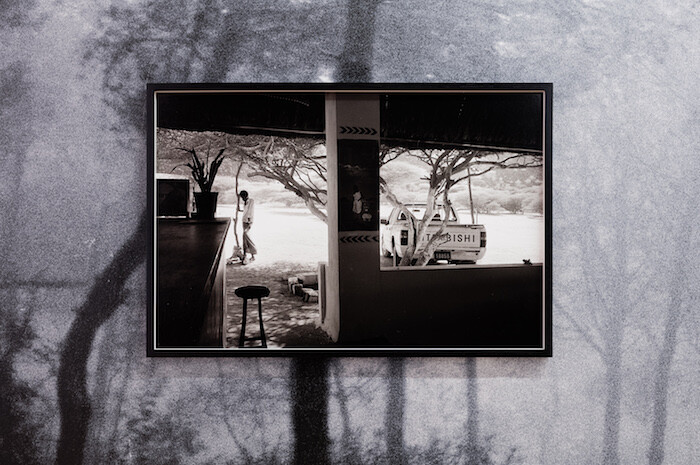

Three photographs hang on the wall, overlapping the wallpaper like a collage: a bar in Djibouti (Bar à sieste, 1987), a street in Rome (San Giovanni in Laterano, 1987), a man sloping off towards a doorway in a Cairo museum (The museum guard, 2012). The images suggest other overlapping historical and political narratives: the Djibouti image was taken before the armed conflict of the early 1990s; the street in Rome is right next to the heart of the Catholic religion; the Cairo image was taken a year after the Arab Spring. Again, however, the affect is paramount. Each location is nearly empty, with a solitary figure, perhaps, adding to the sense of fragility and isolation. In One moment please (2000), a waiter onboard a ferry in Istanbul gestures with his forefinger to an unseen customer—like the subject of a Caspar David Friedrich, he battles the elements, the sea wind tousles his hair, billowing his white shirt, and threatens to upend his tray of crockery.

Elkoury depicts Djibouti, Rome, and Cairo like Eugène Atget’s ghostly and vacant streets. The spectral quality, achieved by Atget with the use of long exposure, is manifest in Elkoury’s extraordinary image of an open air cinema in Djibouti. Odeon (1987) depicts the backs of a seated audience, who have remained stationary enough to be captured, while the screen that they gaze towards is overexposed into a white haze. It is an image that records the passage of time itself, emptied of the particular narrative that has captivated the audience. The analog magic of these images has also become, over time, marked as historic: the cinema has since been digitized, migrated to laptops and smartphones. In this exhibition, Elkoury embraces this digitization in subtle ways. The images here are all inkjet prints, and the wallpaper is also the product of digital technologies. Propped on the floor against another wall is an array of framed photographs, as if recently plucked from Elkoury’s archive—more street scenes, another café, and a color photograph of a block wall with the text “Land for Sail” scrawled on it in red paint. Moreover, the images are regularly changed and rotated, suggesting the vast supply and lossless reproducibility of a database.

Elkoury, it is important to note, is a founder of the Arab Image Foundation, which promotes and archives photographs in the Middle East and North Africa (other co-founders include Samer Mohdad and Akram Zaatari). Like other Lebanese artists such as Rabih Mroué, Walid Raad, and Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, Elkoury is concerned with tracing and preserving memories in the face of trauma and forgetting. What distinguishes Elkoury’s work is that the photographic archives that he mines are his own. For all their encoded politics and history, his works remain as personal and enigmatic as snapshots.