They had been to an opening.

Now they were driving around the island with no aim, he had a fast car. He put the roof down and her hair whipped about her face and neck and shoulders, she was curious to see how long it would take for him to put the roof back up if she said nothing. But he did not put it back up, so her hair was in her mouth when he asked how she found the show.

She took her hair out of her mouth and held it back from her face with one hand and said, I did not like the space. He said that wasn’t his question, she said it affected her answer so it seemed fair enough to say so. He put a hand on her knee and she looked at his hand as first it related in concentric circles his thumb, her kneecap, his index finger, then, perhaps under her stare, it fell quite still, but remained there all the same.

You want to walk in and say yes, she said. You want to walk in and be able to smell it.

Smell what?

The sexual potential of the gallery space, she said. Looking at his face she saw that he had already misunderstood her, but at this point she was much too tired, or lazy, to make him understand. They were about to enter, and so entered, a massive tunnel, the Kallang-Paya Lebar Expressway, asphalt still brilliant. She had never been through a tunnel in a car with the top down before, and when they came out on the other side some five or ten minutes later, his hand was still on her knee. The heat from his palm was muted: but tepid, or warm? Since she was in his car she thought she might as well go with warm, for now.

*

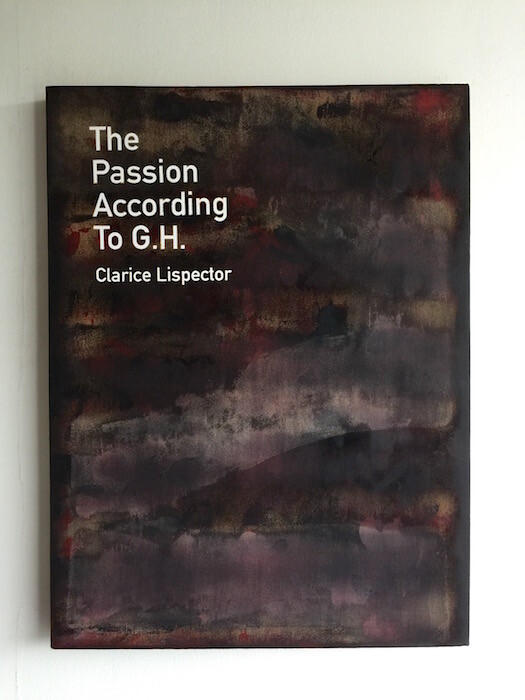

When he, 0.7 km away, swiped right on her, she was looking for Clarice Lispector in the thick of the “L” section at Kinokuniya Orchard where there was Lipsyte and Lovecraft, Lethem and Lodge but no Lady Lispector between them. When she swiped back he did not say hello, he said

There’s an opening

For a bit there was nothing else. She looked at the three and a half words on her screen quite content. She saw that he was typing, she wished he would stop typing and the message, their contact, would end there, but it was followed by

At Hermès

He, Hermès, 0.7 km was only a few malls away. And if you went by the underground walkways that connected so assiduously all the malls on this stretch of Orchard Road you hardly realised you had walked any of that length.

An opening at Hermès was after all something to do on a Thursday night in the city, a city that thought of itself as a country, though his lack of punctuation suggested to her that he’d asked her to an art opening expressly because he thought it would make an impression on her.

She was in an average work dress today—days you did dress up for, nothing ever happened: but didn’t she live for those days, where everything felt empty and she felt dramatic, sonorous—but at least she was in two and a half inch heels, if she went to the bathroom and let her hair down and exaggerated her eyeliner, she would be good to go. She visited the Ion bathroom instead of the Takashimaya bathroom because the bathroom mirrors in Ion were angled better, the light lower.

How will I know you

I’ll smile at you, phone in hand

But that’s everybody

Everybody smiles at you?

She had never been inside Hermès, would likely never have gone in if she had not been invited in or swiped on: now—pushing past the heavy glass doors—now she was a walking cliché of a savvy, single corporate clotheshorse trotting past—ponyskin bags and silkscreened silk scarves, shiny keyrings and riding gloves—goods she had been taught to recognize, although (or more precisely, because) they had no identifying logo on their body, it takes one to know one, to covet—silver tray offered up by boy temping the night in cummerbund, red or white or bubbly—bubbly, heels went well with bubbly, then up a spiraling staircase in the middle of the boutique into the buzz of a third floor room that she now understood as a gallery, secreted away from the street. Later over her second glass of red, they’d run out of the Moët, shame, she happened to trade a few words with an Hermès PR with a big laugh who must have mistaken her for an artist, or, a collector, or, a collector’s wife, who told her, It isn’t every Hermès store in the world that has a gallery component, there are only five in the world. Let me guess, she said, rolling her eyes in a friendly way, New York London Paris Tokyo Singapore? And the woman wagged a finger at her, said, Brussels Tokyo Seoul Lorraine Singapore.

Because there was only one point of exit and entry into the gallery—that precious little stair, and he, smiling at her, phone in hand, met her there, on the landing—it felt to her that the route she wended through the space was predetermined, there was a strict movement expected of her body, and so the space did not make her want to say yes unequivocally, because it did not give her room, to turn and return, though she did appreciate that the white cube was somehow much more spacious than she had expected, ascending from the fastidiously arranged and perfectly lit display of the retail component under.

*

It became a thing, their thing, a gallery night, then a drive around the area and then car sex, the air conditioning left running.

The first time, in a carpark in Liat Towers, after the Hermès show, she’d asked if he wanted to kill the engine. He asked why. How idiotic, innocent really — if he could afford a Maserati he wouldn’t be worrying his head over petrol to keep the air conditioning running. So she did not answer him, only bent over, bit his neck, hard. At which he only moaned.

She had been looking at a modest Mazda earlier in the year and the cost of a Mazda was $95,888 and the Certificate of Entitlement (of Entitlement!) was $53,694, half a car for a piece of paper to have a car proper, and she calculated that against distance and petrol ($2.30 per litre, one of the highest petroleum prices in the world) and all in all decided she was better off taking cabs for the rest of her life, assuming she lived and died here. She did not very often think about mortality and she felt sorry to have considered it in this context.

At Helutrans she said she could smell the sea, later they fucked in view of the port containers and the cranes, World’s Busiest Port!

She worked for the Singapore Tourism Board, selling the city a job hazard ticker tape in her head. Make it sexy, her higher ups liked saying now and she cringed each time, when had sexy entered the civil service lexicon, and what next? He did not say in return what his line of work was beyond Investment, pronounced by him with such discretion that she pictured him as an ah sia kia (she pictured it in Hokkien because she imagined that would rile him the most), gifted for his twenty-first birthday a real-estate portfolio that he did not even himself oversee, content with tearing through tunnels; attending events, parties, dinners, openings, exclusively guest-listed; inspecting artwork; swiping and dining women, because he could, because he could he would.

In the gallery they studied the work (sometimes as he walked away from a painting or an installation or a video he nodded once or twice, announcing the artist’s name in a slightly American accent, or at least with his vowels rising, Charles Lim, he said and nodded, Chun Kai Feng he said and nodded, Genevieve Chua, he said and nodded twice, for no apparent reason, Chun Kai Qun, he said and did not nod, said to her, Twins. Maybe I’ll buy one, and not buy the other.). He asked if Helutrans made her want to say yes and she said it did, but this might only be a seduction of scale, Helutrans was cavernous, it was by far the biggest gallery she had been to here, the ceilings high as in a warehouse, she liked the punk nonchalance that a large, industrial space afforded, and the walls so far apart. It was easy to say yes because in this city you were accustomed to small things. The lighting was fluoro-white, which typically she disliked, but in Helutrans it worked. She said yes I could say yes to this.

She was more sensitive to the sexual potential of spaces than she was to the same in people. She had this one surreptitious move in which she would stand midpoint in a space and open her legs to shoulder width and then unblock something in her pelvic area and evaluate the space, something she had first done in the rooftop chapel of her convent primary school, the light falling through the stained glass, the angular musculature of the space, the empty pews, a rush between her legs that made her want to pee, she spread her legs further apart to see if there would be more or less feeling, a nun came in, said the chapel was closed during recess. Then the nun saw the red string of the Buddhist amulet her parents had her wear round her neck, went down in her habit on an ecclesiastical knee, to say to her gently, searchingly: But are you looking for Jesus?

And she, only eight, had burst into such laughter—flecks of her saliva anointing the nun’s face—that she was sent to detention.

In the car on the way to the parking lot of the port, she said: Have you ever been to a gallery on a day when it was not an opening?

He beat a red light.

He beat a red light from quite far, that is to say he sped up instead of slowing down when he saw that the light was turning red, and then he turned to her and said, I’m sure I have, but I don’t remember.

*

At Sundaram Tagore she said, it’s nothing personal, but.

Sundaram Tagore stood in the middle of a colonial barracks that was now an art cluster, she did not think much of the overall utilization of the space, it had the scent from a hundred paces away of having been fruited from some kind of neoliberal urban blueprint, under the auspices of the Ministry of Information and Communication—which had so recently been redubbed the Ministry of Culture—or, possibly, increasingly these days, the Economic Development Board, or the Ministry of Culture in collusion with the Economic Development Board.

At STB the higher ups told them to keep fully abreast of ongoings like Gillman Barracks, when the local cultural sector was more mature it would be a major tourism strategy, not quite yet but certainly within the next ten years, now it was still Foodie Paradise, Shopping Haven, Multicultural Melting Pot, Uniquely Singapore, but they had to begin laying the groundwork for the softer sell of the next decade, stay ahead of the curve! If I’m still working here in ten years I will have disappointed myself to death, she wrote in her notebook, they were in a boardroom meeting, the lights dialed low, and when she closed her notebook and looked around she had the sense that she would still be there, in ten years, only no longer writing empty asides in her notebook to herself.

Make it sexy!

At Gillman Barracks the spaces varied—the more experimental galleries seemingly allotted the narrower and flatter sites at the very end, while Sundaram Tagore (New York (Chelsea and Madison Avenue) Hong Kong Singapore) had a reputation, was given a central placement in the cluster with a wider, more squarish orientation—so the galleries differed in their coordinates, but to her they smelled the same. She did a quick press release in her head, one of those that when you read carefully made no sense, Vibrant Art Hub Brings Global to Local, but in a pinch sound dynamic.

So she was surprised to feel an intimacy with the Centre for Contemporary Art on the inside (the PR for that was easy, every tagline ought simply to begin “Ute Meta Bauer…”). It felt warm, almost amniotic though spacious, it looked to have been the only purpose-built addition to the site and she saw that they tried to be unobtrusive, likely to keep the integrity of the restored barracks. By-and-large state institutions didn’t interest her, such spaces had too much ego even when they tried to be quiet, were not impersonal enough the way she felt airport terminals or commercial galleries or expensive faceless hotels in the city center—the financial center, not the cultural or recreational center—were: desirable because they belonged only to their ever-changing present circumstance and not really to themselves.

At FOST gallery there was a solo show by a Singaporean artist. On one wall were three rows of paintings, not very large. She was not paying attention, the gallerist was trying to tell them about how they were all paintings of book titles and writers, she was looking at them (actually only reading them, the titles, the writers, not looking at the lines, the bursts, the colors), second row, left to right, Leaving Las Vegas, John O’Brien; Secret Rendezvous, Kōbō Abe; The Elementary Particles, Michel Houellebecq; One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn; Outer Dark, Cormac McCarthy; The Passion According to G.H., Clarice Lispector; Rogue Male, Geoffrey Household.

The gallerist was talking about tension in the lines in the paintwork. Is the artist here, she interrupted the gallerist. He just left, she said, for supper. What is it, he asked, and she said, I’ve been meaning to buy this book (she pointed, he looked, the gallerist looked), but Kino didn’t have it. I was looking for it when you first texted me. Kino to Hermès, remember?’

He looked at the painting closely, was nodding, and turned to her. She thought with a thrill, he’s going to buy it for me! He said: The lines look derivative. She said, From? He repeated, From? She said, Derivative—from? He shrugged and said, Everything comes from somewhere else these days. It’s hard to find the real deal.

Before they left Gillman she went to the bathroom, and when pulling down her panties, noticed that she was wet. She did not know if it was from the CCA or FOST but she liked thinking it was for Clarice Lispector (but was it Clarice Lispector then, or the artist who was taking his supper?). In any case she wiped herself dry, cleaning with toilet paper the translucence from her panties, so he would not inadvertently think it was for him, later. When she was washing her hands, there were three lizards on the mirror, and when they ran from her she saw their undersides in the reflection, like there were six of them.

They parked at Henderson Park.

She came three times.

Much later she called FOST to ask for their price list. But when the gallerist picked up, she put down.

*

Once, she was surfing channels, unable to sleep at four though she had to wake at eight for work, there was a rerun of the Tyra Banks show, Tyra speaking in ingratiating tones with a woman who was a world champion archer who had putatively married the Eiffel Tower, taken legal pains to make Eiffel her last name.

Also some shopkeeper in Leeds who had fallen in love with the Statue of Liberty, and was conducting a transatlantic relationship with it. And lastly a woman in love with a nondescript ferris wheel in Malmö, with whom she felt more sympathy, if not empathy: it was very well to want whatever you wanted but it was another thing to decide for them that they too wanted you back, Erika Eiffel, Amanda Liberty.

And Tyra was trying to ask of Mrs Eiffel, But were you abused sexually as a child?

Tyra wrapped her soft tongue about it, mouthed it respectfully, like a prayer: objectophilia.

After the program as she lay awake she thought how very boring for there to be a base assumption—on the Tyra show, in life, social science, whatever—that everything was philia or phobia, traceable and comprehensible. She thought it was amazing how Freud was like a karaoke favorite—hers was Cyndi Lauper, Girls Just Want To Have Fun, sung blithely in her penultimate nasal key—the more outmoded he was the more you enjoyed the song.

And Monsieur was boring not even because he was an anachronism now, but because he had always, in his own time, used his brain as if it were a penis: linearly, even when he talked about dreams!

She preferred the tacit and the profane.

When could someone take something or someone at face value, and see that this might be the most generous way of understanding him, her, it? And the tacit and the profane only remained tacit and profane if you left it unmolested, content to play on the level of its skin, not because you thought that was all there was to it, but because you valued it in and of itself more than you valued your own understanding of how it came to be.

*

She called Kinokuniya to ask if Clarice Lispector was in stock.

Adult Fiction or Young Adult Fiction?

Adult, she said, trying to keep her voice light and unironic, but then the next question was, So the book is called Police Inspector? She dropped the phone for something to do and when she picked it up she saw that it had cracked, one thin line across the screen. She’d always been so careful.

She dialed him on the cracked screen, asked if he wanted to come over. They’d never been to either of their respective houses, always the Maserati, perhaps he was married, or he still lived with his parents, or his home was not commensurate with the image his car gave off, or, alternatively, his home wildly surpassed the image his car gave off, or he was a car-sex addict, one of those things, she noted that she did not care, not in the least.

His penis was on the small side, but it was somewhat pretty, she barely noticed, or she noticed but did not subject him to the same scrutiny she subjected spaces to. Tonight when he entered her she looked at his face above hers, objectively quite a good looking face but all of a sudden with him moving to and fro with an expression of concentration or pleasure or something in between she thought he looked completely bovine and she would break their semblance of rhythm and begin laughing, unremittingly, if she continued looking at him any longer. So she sighed a small, high-pitched sigh to reassure him before closing her eyes and in her head pictured a gallery, the perfect space, jointed from various locales—a high ceiling here, wattage from there, a heavy glass door that had presence but was not overbearing, either a basement (she’d not seen that yet but thought it promising) or a well-appointed series of windows or full-length glass panels around which the gallery was arranged to make best use of the light, illuminating rather than distracting.

Then he came with a shudder and she counted from one to ten before she gave him a little Sephora plastic bag and asked if he could please take the used condom with him, or throw it into the rubbish chute, which was under the kitchen sink, whichever was more convenient.

Did I do something wrong, he asked. First she thought of saying, Besides that I didn’t come? But then she thought that would not just be cruel, but linear. So she raised herself on her elbows and smiled at him, a real smile, and said, What country is Brussels the capital of?

The Sephora plastic bag rustled between his hand and her duvet as he sat up straighter to answer her: the Netherlands?

She leaned over and pecked the tip of his non-erect penis, bagged the condom gingerly, made a dead knot, put it in his lap and said, I really think you should go now.

*

In Clarice Lispector’s The Passion According to G.H., G.H. cleans out her maid’s room the day after the maid quits. G.H. expects the maid’s room to be a mess, but instead she finds “an entirely clean and vibrating room as in an insane asylum from which dangerous objects have been removed.”

The room was the opposite of what I had created in my house, the opposite of the gentle beauty that came from my talent for arrangement, from my talent for living, the opposite of my serene irony, my sweet and disinterested irony: it was a violation of my quotation marks, the quotation marks that made me a reference to myself.1

Just one thing disturbs the pristine blankness of the room, or perhaps the pristine blankness of the room was designed for the exactitude of this display: on the white wall, black carbon scratches, outlines of a man, a woman, a dog. As G.H. looks at the scrawls, she realizes firstly that she has already forgotten the black maid’s name and much of her face, and, secondly, that the woman had hated her.

*

The lovechild of a young woman, a commercial gallery, and a man with a small penis but a fast car, is a hairless, flesh-colored cuboid, dappled in white, perfectly cut, ninety-degree shoulders. It smells like the burn of hot asphalt. But it is always cool to the touch. If you isolate it and put it on a shelf or a mantel or some such thing, it looks very becoming, even cabalistic though most modest, but if you take it to a construction site and leave it there soon it seems to be part of the brick or rubble and no one will look at it twice. If you hold it up to a mirror, it may surprise you that there is no reflection. And in the middle of its third side: there’s an opening. Admittedly it is hard to say which its third side is because it is a cuboid. The opening suggests an eye or a mouth or an anus but, most of all, a belly-button. It is not quite ready, but you can see that it is there, or about to be there.

Clarice Lispector, The Passion According to G.H., trans. Ronald W. Sousa (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1964/1988), 34.