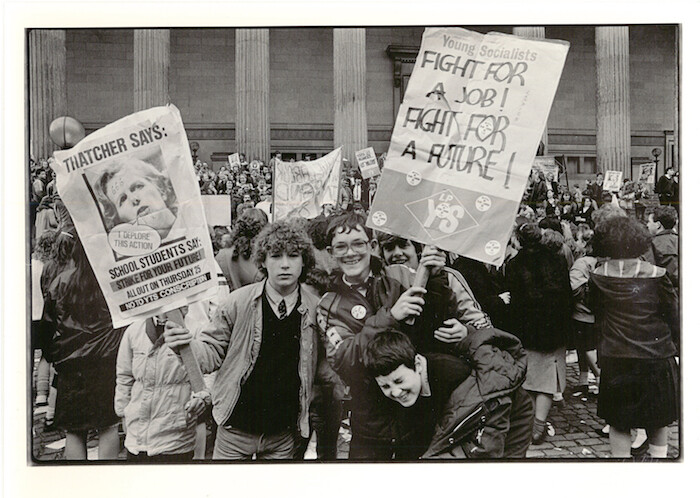

Things happen, and then they happen again, but not the same way, not quite; such is the logic of the biennial. And then there are things which have never happened before, and which happen now and in a time that seems somehow out of time, or takes our “now” out with it. This is how it feels to be in Britain, to be visiting this unashamedly international event exactly two weeks after the country—but not Liverpool1—voted to leave the European Union. While at the launch event there was much talk of this internationalism, and of confidence in the future, a confidence which the city has not always possessed, there persists a more widely held anxiety at what might occur. If the tide has turned, it has done so quickly, receding at a rate which more usually foretells a tsunami to come.

The Liverpool Biennial has neither a single title nor a theme, but rather six “episodes,” although the same work might appear in more than one episode, and more than one episode might appear in the same venue. It is difficult to see how these can operate as discrete Aristotelian elements, “coming in besides” the story when they constitute the story itself, but such an approach—fragmentary, digressive—is well worked overall. The exhibition at Tate Liverpool, part of the “Ancient Greece” episode2 and where many visitors will begin their tour, might be considered a setting of the scene, a bringing together of these elements. In the first case these are antiquities from Liverpool’s Ince Blundell Collection, fragments of sculptures or sculptures made from diverse fragments, resulting in combinations of style, clothing, even gender, in a single work.

This sense of reconstituting an old ideal is one of the strongest themes in the biennial, appropriate to a city blessed with some of the country’s grandest neoclassical architecture; indeed, such buildings stand proudly in the background of Samuel Austin’s 1826 watercolor The Arrival of Aeneas at the Court of Dido, Queen of Carthage at the Walker Art Gallery. Contemporary works by artists including Betty Woodman sit alongside the antiquities, sharing stories, while Koenraad Dedobbeleer’s constructions offer the material support of plinths and tables for their display. If the bringing together of old and new—and the postmodernism of Dedobbeleer’s Germolene-pink tubing—seems dated then perhaps that is the point: in reminding the viewer of the larger structures of James Stirling, the architect of the Tate’s conversion from a warehouse on the Albert Docks (1984–88), the building itself is brought into a broader consideration of civic reconstruction, both conceptual and concrete.

A rather less stable structure can be found in the large, open canning hall of Cain’s Brewery, a ring with a circular arena at its center. Designed by Andreas Angelidakis, the structure is named Collider (2016) after the particle accelerator at CERN, although one suspects that any discoveries made here would be rather less fundamental. But more fun: in the middle is a viewing and performance space for Marvin Gaye Chetwynd’s Dogsy Ma Bone (2016), a film (with some live stagings) based upon Betty Boop’s A Song a Day (1936) and Bertold Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera (1928); if one hears an echo of Bugsy Malone (1976) in the title it is because this, too, has been made with children, who not only performed but also worked upon the sets, costumes, and stagings. As with much of Chetwynd’s work, it is both strange and charmed.

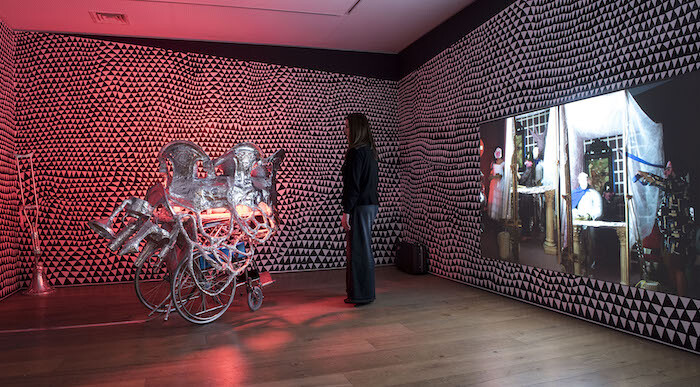

The works that orbit Chetwynd’s do not possess its energy, although one could scarcely say that of the assemblages of Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh, and Hesan Rahmanian that cluster outside. Adopting the characters of three “Submersibles”—Anti-Catty, Princess Rambo, and Space-Sheep—the artists have “smuggled” artworks from their own collection in Dubai—where the Iranian artists live in exile—to Liverpool, hidden amongst other objects, props, and videos. The minor works by major artists including Helen Chadwick, Mona Hatoum, and Robert Mapplethorpe are treated as mere objects, while the other “non-art” objects are brought together in assemblages so urgent that they seem to be going for Baroque. The effect, like the characters’ costumes in the ensemble’s videos, is somewhat monstrous, and if one recalls that this once meant an ill portent, then one might take it as a signal that such works can be found in a number of other venues. Elsewhere, Céline Condorelli’s structures provide a useful, elegant baffle, while Oliver Laric’s 3D-printed Sleeping Boy (2016)—assembled from a scan of John Gibson’s 1834 sculpture Sleeping Shepherd Boy, also in the Walker—remains withdrawn and unperturbed. If he cannot gather all that strays around the space, then he seems content, instead, to gather himself.

Mark Leckey’s Dream English Kid, 1964–1999 AD (2015) is an altogether more compelling gathering of television programs, news reports, even poorly videoed events at which the artist was present, in this case a 1979 Joy Division gig in Liverpool. The rhythm of Leckey’s editing—its syncopations, repetitions—comes from the music he loves, certainly, but it is also powerfully visual. In one repeated cut, Cinzano drools from a woman’s lipsticked mouth, and then urine seeps from the bottom of another’s trousered leg. If the Italian vermouth’s advertising tagline—“Any time, any place, anywhere”—hinted at a sexual availability which its images confirmed, then it might also describe the period’s all-pervading fear of nuclear destruction to be found in the paired shot from the British television drama Threads (1984). Watching this film, I realized that the artist’s name is a homophone for the slang for electricity; it is an appropriately charged, and brilliant, work.

There is fear in Lucy Beech’s new film Pharmakon (2016), albeit more personal, subcutaneous even, but also shared. Christa leads something called “The Healing Grapevine,” a rather organic, communitarian name for something which seems to seek profit from discomfort. The cause of this discomfort is never precisely articulated—doubt seems to be its mode—but it shares something with Morgellons syndrome, a self-diagnosed skin condition which is characterized by itching sensations, the discovery of fibers within the skin, and general medical skepticism: it is more usually considered a form of delusional parasitosis. We follow an unnamed, unspeaking female security guard as she watches over the organization’s activities, and as she works as a bouncer at a nightclub, a metal-detector wand passing over the bodies of women. The anxiety of what—who—is acknowledged and allowed to enter is made real, a boundary enforced or dissolved through the crackle of an earpiece or a nod of the head. “Alright sweetheart, have a good night.” Both pleasure or pain are induced and shared.

The infiltration of bodies by foreign matter is explored in even more forensic detail in Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s Rubber Coated Steel (2016) at The Oratory. On a large monitor sitting between memorials to Liverpool’s civic grandees, we follow an enquiry into the lethal shooting by an Israeli soldier of two teenagers—Nadeem Nawara and Mohamed Abu Daher—in the West Bank on May 15, 2014. The artist—who also works as a forensic audio analyst—was part of a group of experts who concluded that not only had the teenagers been shot with live ammunition rather than rubber bullets, which seemed self-evident given their injuries, but also that the use of such ammunition was deliberately hidden, or silenced, through the use of rubber bullet adaptors on the soldiers’ guns. In its sparse presentation of evidence, and damning testimony, Abu Hamden’s work as an analyst, and as an artist, is as compelling as it is horrifying.

Michael Portnoy is also possessed of a keen ear, and eye. If his targets—the pat assumptions of the art world, especially—are less urgent than extrajudicial state killings, that does not make his performative analyses any less necessary. Over ninety minutes his extraordinary dancers, singers, and improvisors work through nine works under the title Relational Stalinism – The Musical (2016). Sometimes they perform solo, sometimes together, sometimes co-opting—even bullying—the audience in ways simple and absurd. Using a basic grammar of words, phrases, and gestures, the works shift between the tragic, pathetic, dramatic, and comic. But nearly always brilliant. Originally commissioned by Rotterdam’s Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art together with A.P.E. (Art Projects Era), the work was repeated here with only one public performance. If you have the opportunity to see it elsewhere, do so: it may not happen again.

58.2 percent of votes cast in Liverpool supported remaining in the European Union. See “EU referendum: Merseyside split on Brexit,” BBC News, June 24, 2016, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-36619565.

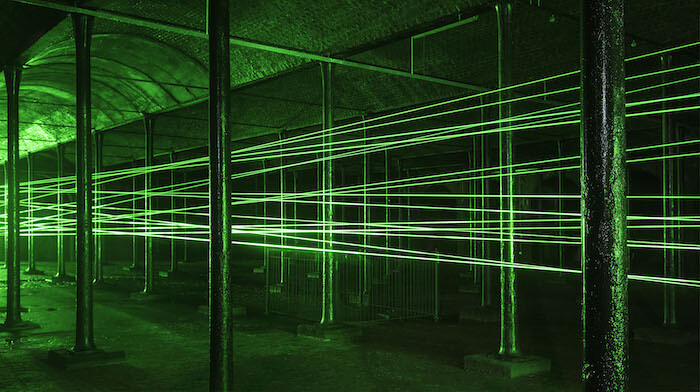

The other “episodes” are “Chinatown,” “Children’s Episode,” “Monuments from the Future,” “Flashback,” and “Software.”