May 5–June 25, 2016

At the apex of art and money, the air is thin and the atmosphere is replaced with rarified pain. Rather than terrestrial life, only blood fortunes are endemic here, whose constituent lifestyles are at least as abstract as the most totemic artworks that give this place meaning. All the vectors involved in Jordan Wolfson’s show at David Zwirner point to such a place of supremacy.

The gallery has accrued spectacular gains during this long boom of the art market, which has endured through a period in which the working and unworking people of the world have seen most of what remains to them siphoned away. The artist has been given the codes to launch his vision without compromise, in an ideal demonstration of what one and the other—artist and gallery—can do for each other within the reigning system of production.

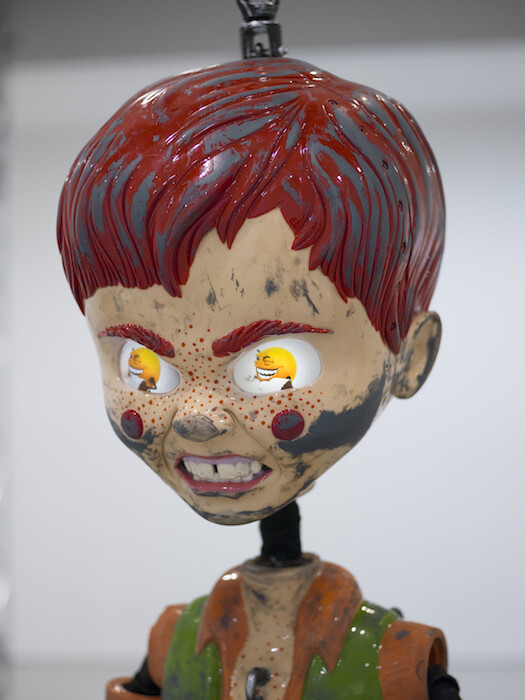

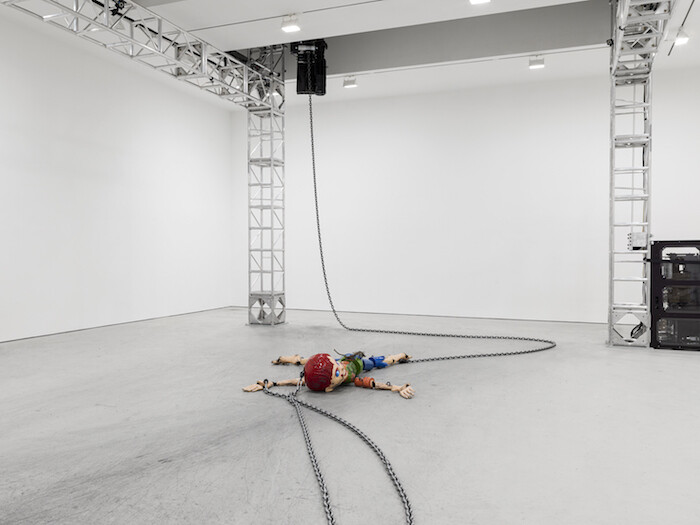

That vision is an inanimate Colored sculpture (2016) of a lacquered, wincing boy, cut up and marionetted by a brutal contraption of chain pulleys in such a way that he is popularly referred to as a robot. This is likely because Wolfson’s breakthrough work, Female Figure (2014)—exhibited at his first solo show with David Zwirner—more conventionally resembles a robot. Two years ago, in my memory, the virality of that animatronic creature might only have been bested by Christian Marclay’s family-friendly film (fetishizing the accumulation of fathomless labor) The Clock (2010), which was still making its rounds of ever more popular museum screenings. As one of its moment’s most visible artworks, Female Figure has an undeniable place in history—and as a display of coalesced abuse and pageantry that compounds this momentum, Colored sculpture is an epoch-defining artwork (from an age of increasingly abbreviated epochs).

The power of the sculpture is hypnotic. Over a 20-minute choreography, the chains drag and spool like snakes, the sounds of metal ratcheting like a roller coaster build and release—critic Ben Davis aptly called this genre of work “adult theme-park entertainment.”1 There’s definitely an orgasmic rhythm to the ballet, whether masturbatory or coital. The vestigial charring of the gallery’s buffed concrete floors is not, thankfully, activated as some kind of performance artifact; rather it completes the mise en scène of a scorched existence in a Promethean nightmare. The high-tech puncta are the child’s LCD eyes, which can recognize human ones and train their gaze on them to eerie effect.

One worries in case the eyes break, as a cracked screen lacks the charm of a chipped arm or disfigured face. They’re a point of weakness in more ways than one. Amid echoing acoustics that recall a high school gymnasium, a male voice (the artist’s) sounds as if he’s resigned to reciting his own words in public, with adolescent opacity: “two to kill you, three to hold you, four to bleed you, five to touch you, six to move you, seven to ice you, eight to put my teeth in you”—throughout these words, the eyes affect a cartoonish trance as they are overlaid with dancing chocolate bonbons with icing spirals, like icons from a slot machine—“nine to put my hand on you, ten to end inside your hair, eleven you’re right over my shoulder, twelve your mouth full of coffee, twelve I knew you, thirteen I killed you, fourteen you’re blind, fifteen you’re spoiled, sixteen to lift you, seventeen to show you, eighteen to weigh you.” After a still denouement: “Spit. Earth.,” the figure crashes and is hoisted up by the skull to be bashed against the ground again and again as it inches across the room. A snippet of “When a Man Loves a Woman” blares and cuts to silence—the kind of menacing audio cue one might expect from a haunted Victrola or as the soundtrack of psycho killer prepping their scene.

The poetry stains what could be an early masterpiece, with qualities both timely and timeless. It doesn’t nearly render the piece impotent—it’s still one the most compelling of the year—but imbues it with unresolved and unpleasant power dynamics. Like plucking the petals off a daisy, the counting narrative paired with the mechanized violence implies a feeling of being tortured by a lover—a woman, loved by a man, if the song has any meaning—without saying anything explicit about what this has filled the strung-up, damaged boy with. Woe? Ire? Hate? It reduces the rawness of the sculpture, which could metaphorically extend to so many types of suffering in this age of pain, to something, intentionally or not, evocative of a tedious brand of heterosexual male privilege.

There was a lot riding on Wolfson when he and Zwirner dropped this new project, without much press or warning, almost akin to a Beyoncé disruption (whose music was a lithe counterpoint to the otherwise wretched, degraded form dancing in the gallery in 2014). Whether haters were holding their breath for a fail or Wolfson’s fans were anticipating an even more sophisticated-looking device, this new work delivers on all desires as unassailably visceral yet trollingly, tauntingly solicitous of condemnation.

Ben Davis, “Jordan Wolfson’s Creepy Robot Art Reboots Jeff Koons,” Artnet News, May 11, 2016, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/jordan-wolfsons-creepy-robot-art-reboots-jeff-koons-493949.