“When racism and sexism are no longer fashionable,” the Guerilla Girls asked in 1989, “what will your art collection be worth?” Predicting that “the art market won’t bestow mega-buck prices on the work of a few white males forever,” their printed notice listed 67 female artists (several of whom are now on show in the refurbished Tate Modern), at least one work by each of whom could be acquired for the price of a single Jasper Johns painting. Once fly-posted around SoHo in a grassroots campaign by the anonymous collective to protest against institutional discrimination in the art world, the poster is now prominently displayed in the world’s most visited museum dedicated to modern and contemporary art.1 The framed portfolio of which it is a part, Guerrilla Girls Talk Back (1985–90)—a scathing critique of the role and representation of women and ethnic minorities in twentieth-century Western culture—hangs opposite Marilyn Diptych (1962), Andy Warhol’s paean to American sex, money, and cultural imperialism.

The new Tate Modern brings forward the future envisaged by the Guerrilla Girls at the expense of a past embodied in Marilyn. The opening of a vast new wing—a coiled, ten-storey ziggurat designed by Herzog & de Meuron—is the occasion for a comprehensive reshuffle of the collection that affords greater (which isn’t to say sufficient) recognition to artists born without the advantage of a white, western, male identity. Three quarters of the works on display have been acquired in the past 16 years; one half of its “solo presentations” are by women artists; more than 50 countries are represented; over a third of all works are by women (up from 17 percent when the Tate Modern opened its doors in 2000). The stated aim of the extension is to accommodate the future of art by allocating greater space to performance, film, and an expanded collection; the unstated aim is to shape that future by rewriting its recent history.

Those two principles are married in Alexandra Pirici and Manuel Pelmuş’s Public Collection Tate Modern (2016), which greets visitors to the Tanks, the cavernous subterranean spaces devoted to live art and film. Five performers use their bodies to act out canonical works of modern art—from Mark Rothko’s “Seagram Murals” (1958–9) to Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (1966)—amidst a landscape of sculptures by Rasheed Araeen (Zero to Infinity, 1968–2007), Robert Morris (Untitled, 1965), and Charlotte Posenenske (Revolving Vane, 1967–8). The performance celebrates the museum’s holdings while puncturing our reverential attitude towards the objects contained within them, literalizing the oft-stated but little-observed maxim that a work of art exists in, belongs to, and should be judged by, the present situation as much as the past. This healthy disrespect towards the work of art as sacred relic—I laughed out loud when, elsewhere in the museum, I came across Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917, reproduced 1964) in a room offering children the opportunity to touch and feel artists’ materials—is symptomatic of an overarching curatorial vision characterized by a mistrust of grand historical narratives.

Indeed, it’s remarkable how many of the most fêted works in the collection have been, if not relegated, then at least removed from the pantheon and asked to battle it out with less celebrated peers. Hung close to, indeed in the firing line of, Roy Lichtenstein’s exultant Whaam! (1963), Beatriz Gonzalez’s Pop-inflected indictment of government corruption and decadence in Latin America (Interior Decoration, 1981) reminds us that the United States’s military and economic hegemony in the second half of the twentieth century had consequences beyond comic books and Elvis. Piet Mondrian’s Composition C (No.III) with Red, Yellow and Blue (1935), meanwhile, is reinvigorated by its proximity to the Neo-Concretists in a room dedicated to the artists and ideas to emerge from Brazil in the 1950s. Labeled “A View from São Paulo,” this is one of a number of displays attempting to refocus art historical attention on cities (Buenos Aires and Tokyo also feature) beyond the traditional centers. The selection of locations is conservative and the elevation of such figures as Lygia Clark, Lee Ufan, and Hélio Oiticica hardly constitutes a risk, but these are steps, however small, in the direction of a more multipolar understanding of contemporary culture.

The new hang is punctured by further intimations of a dry, even mischievous humor. It is tempting, for example, to read the placement of Marwan Rechmaoui’s Monument for the Living (2001–8) beside Rachel Whiteread’s photographic portfolio Demolished (1996) as a metonym for the overall display. If Rechmaoui’s scaled sculpture of a war-torn Beirut high-rise is a phallic symbol, then Whiteread’s photographs of detonated tower blocks in east London must by extension symbolize the dissolution of old patriarchies. The analogy is far-fetched—and there’s a more straightforward point to be made about the resemblance of the Lebanese artist’s sculpture to Whiteread’s famous House (1993)—but these new combinations do at least encourage imaginative speculation, rather than dictating received wisdoms about the relationship of art to modernity (and time, and war, and technology, and media, and individual freedoms…) by hanging this Parisian cubist next to that New York expressionist.

The broadening of horizons extends to the museum’s greater emphasis on film and live art, provided with a permanent home in the Tanks and incorporated into the wider display through a series of screening rooms and performances amidst the collection. Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Primitive (2009), a multi-part installation presented on eight variously sized screens and projections in an encompassing circular configuration, makes impressive use of the daunting underground space. This dreamlike meditation on northeast Thailand’s traumatic history, in which events around the communist insurgency are recycled and reimagined by a cast of teenagers, offers further support to Faulkner’s (and, we might surmise, the curators’) conviction that not only is the past “never dead, it’s not even past.”2

The conversion of this former power station exemplifies that principle. Herzog & de Meuron won the tender for the original project because their proposal allowed for the preservation of the building’s industrial character, and their extension continues to make a virtue of “found” spaces, most notably the clover-shaped underground oil tanks. From outside, the sharp-edged buckle of the new tower looks brooding and implacable; inside, light washes through the latticework cladding and over shimmering concourses, while a bridge over the Turbine Hall links the new wing to the old. That visitors are encouraged to circulate around the museum rather than dutifully follow a stipulated path is consistent with a non-prescriptive curatorial approach that rejects linear, strictly chronological readings of art history.

In the six storeys above that bridge, however, is no art. Two floors are given over to outreach, education, and (ominously) events; others to a “member’s room,” staff quarters, and a restaurant; the uppermost serves as a viewing platform. These provisions are each indicative of the diverse and increasingly onerous responsibilities thrust upon the Tate as a public institution under austerity: to generate revenue from its own sources; to fulfill an increasingly broad educational and social role; to serve as a flagship for London’s burgeoning tourist industry. It’s also possible to discern those pressures in the relative orthodoxy of the exhibition program across its two London museums, which is heavy on crowd-pulling blockbusters—Alberto Giacometti, Amedeo Modigliani, Wolfgang Tillmans—and light on experiment. It is to be hoped that the temporary exhibitions will, in time, come to demonstrate the same commitment as the permanent collection to women and artists of color working in a wider variety of media.

Performance, film, and installation are united in Suzanne Lacy’s The Crystal Quilt (1985–7), which opens the “Performer and Participant” display occupying the third floor of the new wing. That a public artwork which engaged older women in the Minneapolis area through a program of workshops, exhibitions, and collaborative performances should occupy such a prominent position in the museum feels quietly radical. A further series of bold decisions—the allocation of a room to Lorna Simpson’s photographic explorations of race and gender, Twenty Questions (A Sampler) (1986) and Five Day Forecast (1991); the space given over to Ana Lupas’s large-scale, lyrical-political The Solemn Process (1964–2008); a sprawling multimedia display devoted to Margaret Harrison, Kay Hunt, and Mary Kelly’s study of female factory employees, Women of Work (1973–5)—serves to elevate the politically engaged above the sensational. The gleaming baubles of late capitalism are remarkable, on the whole, by their absence.

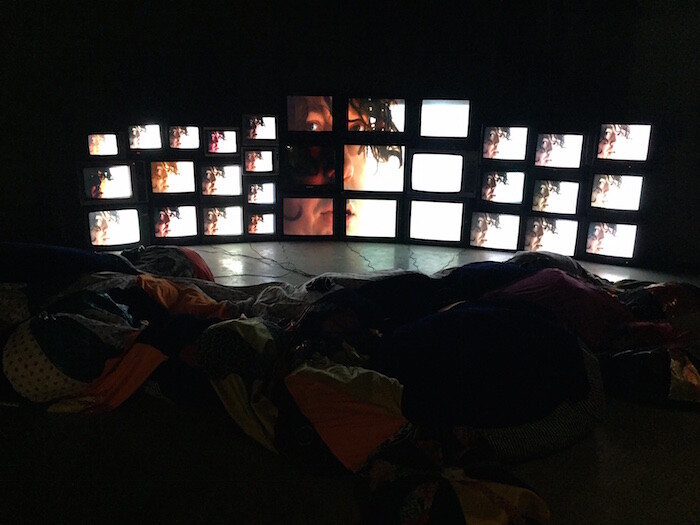

That this occasionally feels like an expression of how art history should have been, rather than how it was, is one objection. The sometimes unimaginative presentation of the work is another, with monumental sculptures ringed around by works hung on, or pressed up to, the wall: Bruce Nauman’s Corridor with Mirror and White Lights (1971), for instance, is pinned to the back of a capacious new gallery devoted to minimalist sculpture. This somewhat drab display of vast, geometrical forms in post-industrial materials—only partially enlivened by the peephole menace of Mike Kelley’s Channel One, Channel Two and Channel Three (1994) and Joan Jonas’s performance film Songdelay (1973)—betrays an attachment to the densely theorized artistic revolutions of the 1960s that (depending on your taste) either anchors or skews the museum’s replenished collection. Amidst all the jagged steel and concrete, the colorful bunting held aloft by two previously unacquainted performers for Amalia Pica’s Strangers (2008) feels more like a concession to the need to seem innovative, contemporary, and interdisciplinary than an integral part of a coherent display.

Indeed, for all the spectacle of its new wing—its twisting central staircase, the brute underground spaces, the gleaming new galleries—there is little sense of the institution breaking new ground, laying down a revolutionary template for the museum of the future. Yet the curatorial decisions guiding its new configuration amount, collectively, to an understated ideological agenda predicated upon gender equality, internationalism, and the desire to find common cause between times and places rather than identifying difference. Renata Adler wrote that “the radical intelligence in the moderate position is the only place where the center holds,”3 and this new museum strikes a balance between past and future, marginal and mainstream, local and global. At the beginning of a summer in which things in this country and elsewhere threaten to fall apart, that feels like something to be cherished.

“The New Tate Modern Opens,” press release (June 2015), http://www.tate.org.uk/about/press-office/press-releases/new-tate-modern-opens.

William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun (New York: Vintage, 1950/2011), 73.

Renata Adler, Speedboat (New York Review Books, 1971/2013), 41.