When word got out that Hervé Falciani, a dapper systems engineer at HSBC’s hushed private bank in Geneva, had lifted the identities and details of 130,000 account holders in 2008, the Swiss government was put in the unfortunate position of having to ask its neighbors to extradite this thief or Robin Hood, depending on one’s perspective. These were the same countries whose own citizens had evaded paying taxes on the cash (often wrapped into bricks, sometimes in faraway, foreign currencies) by storing it with HSBC’s Swiss branches. France sheltered the whistleblower and his “Lagarde list,” even sharing the embezzled data with other state governments to help them further their own pursuits of missing tax income, often from its wealthiest citizens.1

The centuries-old Swiss banking tradition of total discretion, even at its highest stakes, was finally broken. Falciani was not only a highly skilled technician, he was also an astute witness of both formal and informal office protocol. This was vital, since there was often no official documentation to refer to, or dispute: the majority of the private bank’s clients opted out of receiving monthly bank statements, a process detailed in a recent New Yorker profile that reads like a Hollywood script.2 To avoid any record of transaction on these opaque accounts, HSBC bankers accommodated their clients’ anxiety by occasionally arranging by payphone a meeting in a café to hand over cash, later deposited into their accounts when the banker returned to the office. No official records were kept of this deposit. The risk, and even more urgently, the thrill, of such a quotidian exchange seems not only plausible, but familiar: this plays out like the quintessential art-fair meet-up, situated ideally in the small, wealthy—wealthy for Switzerland, even—town of Basel. The fair’s 47th iteration runs this week, carrying on a long tradition of brisk business through codified language, small interactions, verbal assurances, and handshakes. Artworks serve many purposes beside their conceptual and formal ones—as status symbols, as investment objects, as insurance guarantees—and banks are more than warehouses for bills; you come to Basel (wherever that Basel may be, given the fair’s multiple locations worldwide) to trade in commodities.

With the country’s tax-haven laws shaking off their neutrality, and therefore their global advantage, the freeports and shell companies flowering in Monaco, Singapore, and Luxembourg seem to be under less scrutiny than in the Alps.3 One can find these agencies, capable of directing economic traffic, reflected in the contents of the fair. There are the monumental works claiming their territory by the square meter: a forest of gleaming black John McCracken planks at David Zwirner (New York) and Ai Weiwei’s White House (2015) at neugerriemschneider (Berlin), a whitewashed skeleton of a building balancing on crystal balls, both in the fair’s Unlimited section; Raphaela Vogel’s Teint Eklat (2014) at BQ, Berlin, an irresistible, towering T-Rex admiring its own shadow; even Lawrence Weiner’s massive PVC banner MEIN HAUS IST DEIN HAUS DEIN HAUS IST MEIN HAUS WENN DU AUF DEN BODEN SCHEISST GEHT’S AUCH AUF DEINE FÜSSE (2014), cheekily hanging deep inside the Gymnasium am Münsterplatz, Switzerland’s second oldest school, as part of Parcours, the fair’s series of site-specific installations throughout the city. There is also a strong current of works which slip in between, which use these—perhaps it would be unfair to categorize them as Swiss—strategies of discretion through understated gestures. Delicate, fragile works on paper by Richard Tuttle and Fred Sandback, for example, at Zurich’s Annemarie Verna Galerie space, habitual prizes at the top of the market, betray nothing of these market flows in their economical markings.

Over at Unlimited, the fair’s mute carnival of booth-unfriendly works—performances and colossal funhouse structures sharing one open space—are the conceptual answer to Circus Knie, a proper ponies-and-popcorn circus camped across the street of the Messeplatz for a couple of weeks. (An Art Basel information board is planted at the entrance, but despite all of the pensive glance-overs of the magenta big-top from second- and third-time fairgoers hoping to see some real action, Knie is a coincidental production, not an offsite installation.) At least we get Mimed Sculptures (2016), Davide Balula’s troupe of charming mimes, all in crisp white outfits and fuchsia gloves. Each performer mimes a historical sculpture from the mid-twentieth century, by the likes of Louis Bourgeois or Barbara Hepworth. Subtle twists of the performers’ hands are the only indications that any form exists, and this line disappears when the hand moves on.

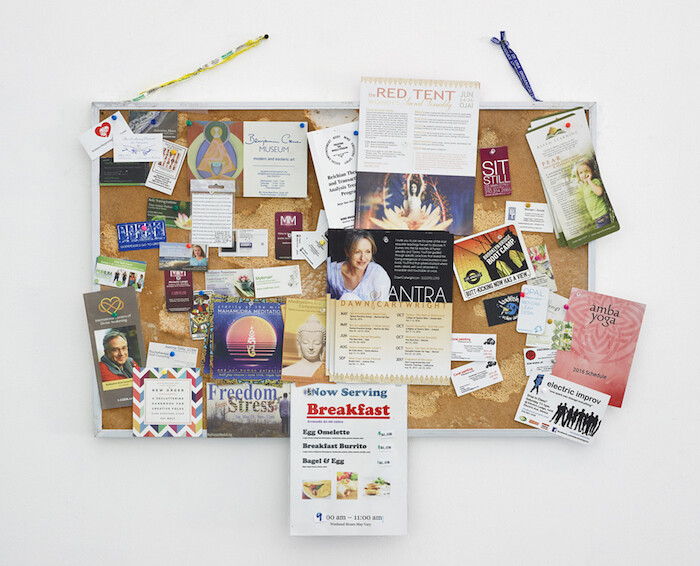

In Parcours, this year curated by Samuel Leuenberger of the invigorating Basel project space SALTS, works also obscured themselves, withholding even more while in public. Daniel Gustav Cramer’s Coasts (2016) consists of single stacks of sound equipment placed within the rooms of an emptied townhouse on St. Alban-Vorstadt. The hissings were recorded by the artist off various coasts—Australia, Portugal, California—and the waves of white noise wash over each other when one walks from room to room. The generous visual presentation of sophisticated equipment playing in this beautiful home still suppresses any context that it could provide for the source of the audio recordings—if anything, the work’s visible aspects further confuse its current location and its provenance. Occasionally, an artist will draw her audience a map: at LISTE, for Auckland gallery Hopkinson Mossman, Fiona Connor has recreated message boards found in public corridors in Los Angeles—at health food stores, cafes, yoga studios—and nailed down these fleeting notes, reproducing them in lifelike printed aluminum to preserve the offhand scraps of paper charting the directions of social networks’ flow.

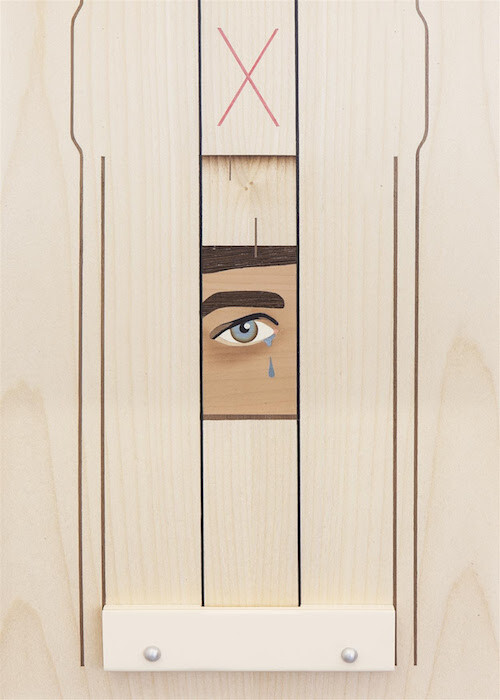

Even romance and curiosity can be modulated here, even when completely vulnerable and exposed. Camille Blatrix’s panels (all 2016)—flat, uneasily utilitarian wall works on view at Balice Hertling (Paris), also at LISTE—are composed of boards of blonde wood, mushroom-colored plastic, and metal in careful intersections and oblique windows. They frame the semi-anonymous small mementos inlaid in 18th-century French marquetry from his gallerist’s recent breakup. A lone matching wooden Band-Aid, taped to the wall, offers a tiny bit of shy healing. At mother’s tankstation, from Dublin, Yuri Pattison’s Dust Scrapers (2016), sleek acrylic boxes displaying the stylized inner machinations of laptops, have been doctored to turn the computers’ fans inward: instead of cooling off the appliance, the boxes draw in the dust and hair of passersby, inputting our data to form a portrait of us and, like Google and Facebook ads, sell it back to ourselves. A data theft less severe than Falciani’s, but just as incriminating.

Patrick Radden Keefe, “The Bank Robber,” The New Yorker, May 30, 2016, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/05/30/herve-falcianis-great-swiss-bank-heist.

Ibid.

Georgina Adam, “2015’s biggest art market developments and what they mean,” The Art Newspaper, December 23, 2015, http://theartnewspaper.com/market/art-market-news/2015-s-biggest-art-market-developments-and-what-they-mean-/.