Since it is impossible to say—in the work of K.r.m. Mooney just as in the world—where one thing ends and another begins, it seems appropriate to start by considering the structure that houses this exhibition. An ancient wooden shed, it was once a garage for the large Craftsman home it sits behind, built in 1906. Wide sliding barn-like doors open onto patched timber walls and a cracked concrete floor stained from years of dripping motor oil. Weeds sprout through some of the cracks and papery pink bougainvillea petals blow in from the garden. As a concession to the aesthetic formalities of the white cube, a pristine white rectangle of wall divides the front gallery from the storage area behind.

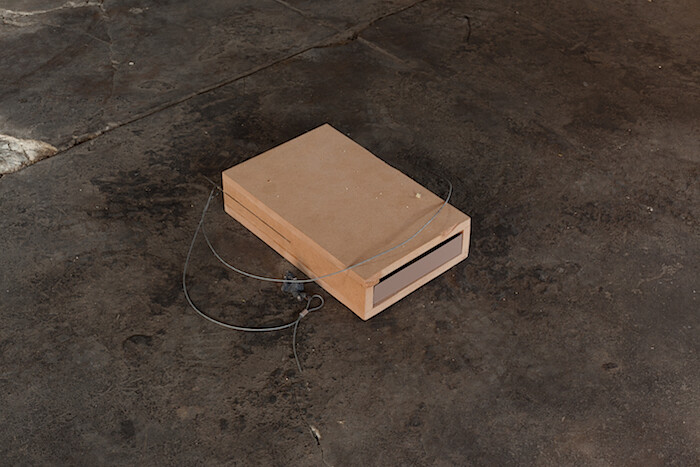

There are only two artworks on the checklist, though the exhibition—titled “Oscine”—comprises many more parts. A case in point: the first work on the list, Accord, a chord (all works 2016), consists of two small box-like sculptures placed on the floor of the gallery. A diptych, if you like. Their dimensions reminded me of external hard drives or books—dictionaries perhaps. Both allusions are pertinent. As with most of Mooney’s work, each is a combination of modified and crafted elements: in this instance, composite particle board, steel cable, and aluminum sheeting along with less prosaic items like a cast silver chanterelle mushroom and a silver-plated dog whistle. The work’s title points to the dynamic between harmony and individuation that informs Mooney’s choice of media.

Not on the checklist are several interventions around the space, most of which would be easy to miss if the gallerist, Ben Echeverria, did not point them out to you. It is hard to say which is more subtle: the tiny tangles of wire that Mooney found and removed from the site, sandblasting them to exaggerate their deteriorated appearance, then nailing them back onto the shed’s outside wall, as if they had never left, or the single stem of millet, pinned just beneath its seed head (identifiable because the plant is listed as a material for other works in the show). These additions feel like talismans of some kind—think of the first season of the TV series True Detective—though they seem intended for good rather than evil.

More substantial, though unassuming in a different way, is the aluminum-framed window that Mooney has fitted in place of the former wooden one. Its light-industrial styling offsets the rusticity of the space and of the natural elements in the exhibition. The indeterminacy of the window, which is both an object unto itself and a mediator between the architecture, its location, and its contents, is analogous to Mooney’s sculptures’ interaction with their surroundings. Is the gap between the window and the wooden wall a part of the window? I would have to say yes. What about the light that is filtered through its glass? And what about the light when—as on my visit—the window is open?

The sculpture that shared its title with the exhibition, Oscine I, was to be found in the back of the gallery, past the white wall and wired to the wooden frame of an original window. Like many of Mooney’s works, including Accord, a chord, it is a repository for other things. In this case, a narrow frosted glass dish holds some more millet, a small cuttlebone, a piece of fishing line, a curling length of wire, and a silver-plated steel rod. (Mooney was a jeweler before exhibiting as an artist.) It contains other things, such as the daylight that falls through the glass and, at night, the sodium glare of a streetlamp. It also contains ideas: a set of loose relations between the former lives of these objects, their functions and symbolisms, and their compositional qualities. The work is a still-life arrangement just as it is a reliquary of charms.

Another kind of container is a library. As with every exhibition at Reserve Ames, a curator, artist, or writer has been invited to respond to the artist’s work with a collection of books. For Mooney’s exhibition, curator Anthony Huberman has assembled a concise library of six small-run publications, all with spare white jacket designs. A book about the little-known rings designed in 1972 by Dieter Roth sits alongside a reprinted essay by William H. Gass on the word “and.”1

Oscine is a taxonomic term for songbirds. It is appealing to think of these artworks as small creatures perching on a given structure, transmitting their unique calls in the hope of hearing a reply. The wires that arc over and around Mooney’s sculptures might just as well be antenna for improvised broadcasting equipment. Or—given their mute self-possession, crackling with potential energy—for bombs.

Jean-Christophe Ammann and Dieter Roth, The Rings of Dieter Roth (Lucerne: Edizioni Periferia, 2006); and William H. Gass, And (Amsterdam: Colophon and Silver Fern Press, 2011).