The opening of a temporary exhibition space co-hosted by Andrew Kreps and Anton Kern, at a new gallery complex called Minnesota Street Project in San Francisco’s Dogpatch district, was timed to correspond with the arrival of the international art world elite to fête SFMOMA. These openings and reopenings come at a moment when the future of the Bay Area art scene seems uncertain. The new SFMOMA, billed after three years of refurbishment as the largest museum dedicated to modern art in the country, is a major tourist attraction—but what impact will it have on the local arts economy? The opening has already inspired galleries from New York to set up shop in San Francisco, but will it help make San Francisco’s existing scene more visible, or damage it as burgeoning collectors (read new tech wealth) buy established names rather than investing in young Bay Area-based artists? Will these developments help keep artists in San Francisco or force them out?

Designed by Snøhetta, the new SFMOMA’s spacious galleries are empty containers suited to the blue-chip work within. The impetus for the expansion was the 100-year-loan of the private collection of Gap founders Donald and Doris Fisher. During the press preview, Donald’s son Bob Fisher declared “my father liked big powerful works of art,” an accurate description of much of the collection. Postwar German abstraction, Minimalism, and Pop Art loom large. A room of Agnes Martin paintings is alone worth the price of admission, and a retrospective of Ellsworth Kelly is opportune. Things begin to falter by the seventh floor, dedicated to the Campaign for Art, an unusual approach to building the museum’s contemporary collection by allowing curators to cherry-pick pieces from local collections. The results match the premise: much of what is being shown reflects market trends, rather than taking risks and presenting work not easily bought and sold.

The most exciting work occurs in the few artist commissions sprinkled throughout the building, which are swallowed by the grandiose group shows unless you seek them out. Leonor Antunes’s constellation of six interconnected sculptures forces an awareness of the surrounding architecture, and formal elements coalesce with historical references in an environment set apart. Thick black leather sheets hang from rope attached to the ceiling in discrepancies with backus house (all works 2016) while five lamps, modernist light fixtures that sprout from the floor, illuminate the area. A skylight alley running sideways, a three dimensional grid of red, off-white, and black brass triangular plates, is inspired by a lamp designed by Greta Magnusson-Grossman; a delicate hanging piece, a spiral staircase leads down to the garden, references Bay Area artist Ruth Asawa; and enlarged with verticals is a floor piece based on a weaving by Anni Albers. These nods to twentieth-century female artists make even more apparent the lack of women (not to mention artists of color) throughout the rest of the museum. Outside of SFMOMA it’s actually a good moment for female artists in San Francisco, with important solo shows by Laura Owens at the Wattis,(1) Mariana Castillo Deball at San Francisco Art Institute, and Yin-Ju Chen at Kadist.

Jason Lazarus’s Recordings #3 (At Sea) (2014–16)—included in the group exhibition “About Time: Photography in a Moment of Change” at SFMOMA—challenges the definition of photography, a pushing of boundaries that the museum should emulate if it wants to contribute meaningfully to dialogues around contemporary art. Lazarus has been collecting other people’s discarded photographs for years, and here only the versos of photographs are visible, displaying handwritten text that is both tantalizingly intimate and maddeningly unsatisfactory. Owen Kydd (whose work is also on view at Casemore Kirkeby, a new gallery housed in Minnesota Street Project) also tests the limits of the medium in Composition, Warner Studio (on Green) (2012), a static-perspective video of a black garbage bag flapping in the breeze.

Across the street from SFMOMA, Gagosian Gallery has opened a Bay Area outpost that essentially functions as an extension of the museum. The only differences are the natural light streaming in from a skylight and the fact that all the work is for sale. Its opening exhibition is titled “Plane.Site,” and the loose theme concerns artists who work in both two and three dimensions. All but 3 of the 16 artists in the show are in SFMOMA’s collection, and a museum visitor impressed by Richard Serra’s monumental work Sequence (2006) can even purchase their own domestic-appropriate sculpture Malmo Roll (1984) at Gagosian.

Minnesota Street Project (MSP), funded by philanthropists Deborah and Andy Rappaport, opened in March with 10 commercial galleries and the promise of 30 subsidized studio spaces to come. The quality of exhibitions is inconsistent, but Et al. etc.—a second gallery from Chinatown’s Et al.—and the aforementioned Kern/Kreps collaboration make it worth the trip. The two spaces share the same goal—to expose a Bay Area audience to art from elsewhere— but take very different approaches. Et al. etc. is operating under an unusual premise: the space is divided in half and a gallery from another city is invited to present a parallel exhibition. In May a somewhat abstruse but intriguing exhibition by Queer Thoughts from New York included a pile of large-scale cinnamon sticks called Peaceful Protest (High Tech) (2016) by Lulou Margarine; an inkjet print of a politically tattooed hand holding a Kindle open to a botanical drawing of the hallucinogenic mandrake root, Let’s Consume (2016) by Stefanos Mandrake; and Mindy Rose Schwartz’s altar-like sculpture of kitschy objects centered around a disquieting river scene, Before (2008).

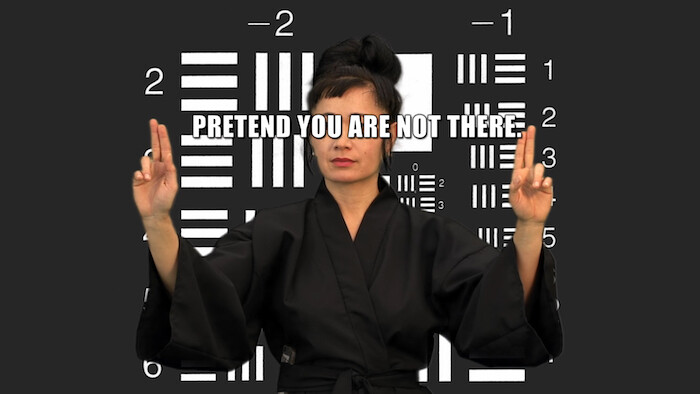

Kreps and Kern brought a strong group of artists not usually seen in San Francisco to MSP, which made it possible to overlook the lack of a theme tying the work together. A big, colorful marker on cardboard piece by Andrea Bowers, Intl. Women’s Day (Illustration by Heriberto C. Echeverria Del Pozo, Cuban Communist Party Publishers, 1972) (2015), is based on an image of a female activist from the artist’s collection of agitprop ephemera and seems particularly urgent in San Francisco’s current political climate. In the screening room at MSP, Hito Steyerl’s video How Not To Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational MOV. File (2013) advises on how to avoid detection in the era of digital surveillance, from being an undocumented worker to living in a gated community.

FraenkelLAB—a hipper off-shoot of photography stalwart Fraenkel Gallery—opened in April with “Home Improvements,” a lightweight group show with an affection for the quotidian, curated by John Waters. The works on show ranged from Martin Creed’s Work No 2340 (2015), a collection of cheap plastic shopping bags framed under glass with a cheeky reference to Minimalist painter Robert Ryman, and to Gelitin’s Untitled (2012), a tower of brightly colored stuffed animals that collapses when you step on a foot pedal. Jessica Silverman Gallery remains committed to its beautiful space in the Tenderloin and has just opened a temporary project space across the street. An elegant exhibition of Isaac Julien’s large-scale film stills, primarily from Looking for Langston (1989), beguiles in the principal gallery.

In January 500 Capp Street, the home of legendary Bay Area conceptual artist David Ireland (1930–2009), opened to the public after intensive restorations. The Mission district house is an artwork itself, full of site-specific installations that blur the boundary between art and everyday life. Ireland purchased the house in 1975, and 40 years later it seems impossible to imagine an artist buying an entire home, particularly in the Mission, now the epicenter of the tech housing market.

Artists have always left San Francisco for larger cities with greater visibility like New York and Los Angeles. What’s particularly disheartening is that now artists are moving to New Orleans and Pittsburgh, Boston and Chicago, suggesting less a yearning for something bigger than a need for something more affordable. With its influx of tech industry money, San Francisco may no longer be a place where artists can thrive outside the pressures of the market. Artists will need to adapt, but more significantly, these new galleries and non-profits will need to engage and support local artists at the same time that they welcome tourists and woo collectors.

(1)The author recently started working at the Wattis Institute.