Best known for her alternately macabre and humorous sculptures—body parts cast in polyester resin, anthropomorphic wads of used chewing gum, plastic lamps featuring disembodied red lips or pink breasts, and Carrara marble belly rolls—Alina Szapocznikow also made hundreds of drawings over the course of her short career. Following a renewed interest in Szapocznikow’s work, as evidenced by several high-profile retrospectives in recent years (at WIELS in 2011/12, travelling to the Wexner Center, the Hammer Museum, and MoMA; the Pompidou Center in 2013; and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 2014), the current exhibition at Galerie Loevenbruck focuses on a series of drawings made just before her untimely death in 1973, aged 47. Presented alongside a single sculpture from the same twilight period (Head of Piotr, 1972, a haunting cast-polyester bust of the artist’s son), the nine “Human landscapes” on view are eloquent and sensual illustrations of collapse, decay, and rebirth.

Szapocznikow’s use of color in this series—a rarity in her drawings—adds a surrealist dreaminess to her signature “disarticulation of form.”1 A sparingly applied, limited palette of pinks, greens, yellows, and browns underscores the simultaneous frailty and vigor of Szapocznikow’s fragmented subjects. Watery pink figures are at once translucent and ghostly as well as flushed and vibrant. Washes, sometimes layered, of browns, greens, and yellows, meanwhile, create chromatic links and overlaps between the environment and its inhabitants. As flesh bleeds into landscape and earth washes over the body, the distinction between figure and ground becomes unsettlingly blurry.

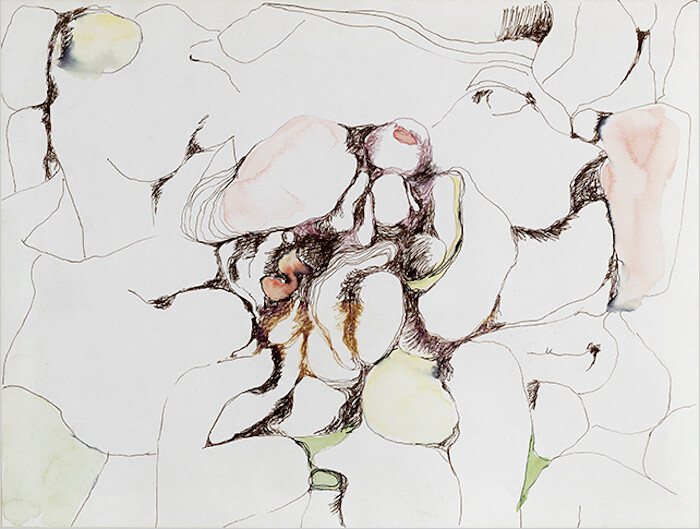

Verging on abstraction, the bodies and body parts delicately represented in pen, ink, and watercolor commingle with their environments in morbidly erotic ways. In Human landscape III (1972) a rugged outcrop outlined in black felt-tip pen contains a mishmash of biomorphic fragments and geological forms. Jumbled together towards the center of the composition, a pale pink torso lies next to a hair-lined orifice, an indeterminate red organ (intestines or perhaps lungs), and a pair of elongated foot-like appendages. Towards the top of the pile, a small pink oblate form resembles plump lips on an otherwise featureless and colorless head. Interspersed around this discombobulated and eviscerated figure, greenish daubs and yellowy washes evoke mossy rocks and muddy streams. The intimate relationship between human and nature is clear, but whether this particular body is being absorbed by the landscape or emerging from it remains ambiguous.

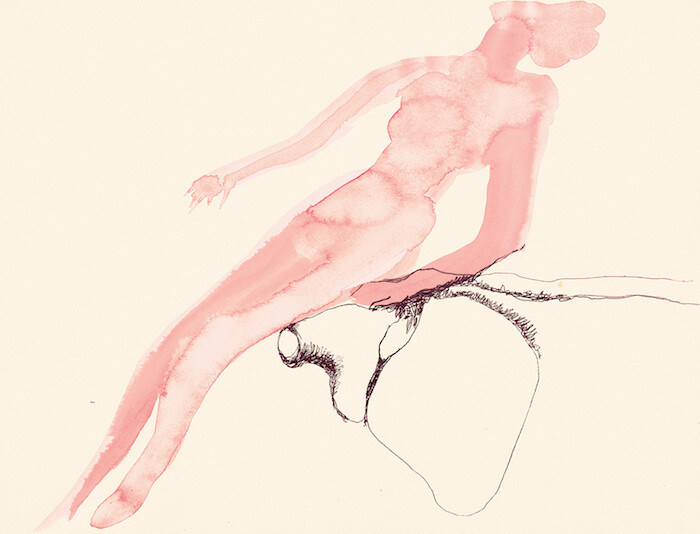

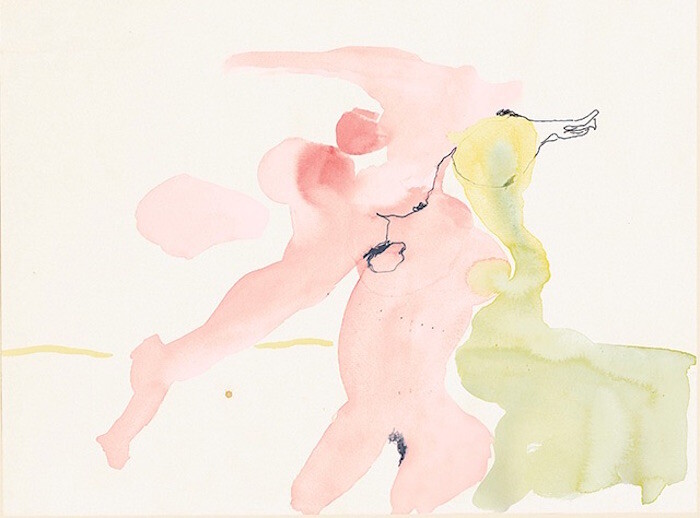

Elsewhere, body parts fused (and confused) with the landscape evoke a relationship between humans and the earth that is simultaneously grotesque and sublime. In Human landscape (ca. 1971–72), Szapocznikow forgoes pen outlines and paints two pink bodies hovering in a balletic embrace. The headless couple floats upwards, leaving behind a thin yellowy-green horizon line. Implicitly heaven bound, the merged bodies suggest a polymorphous angel. Another Human landscape (also ca. 1971–72) imagines an erotic interlude between a woman and a phallic rock formation. Leaning back, the pink female figure arches her back in ecstasy while caressing the craggy erection beneath her.

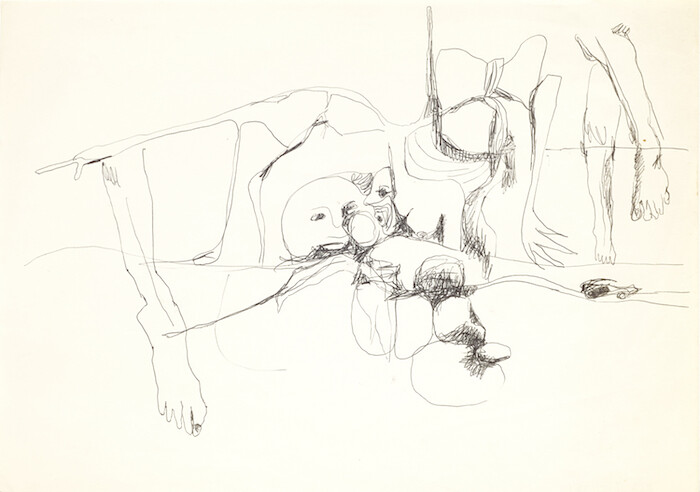

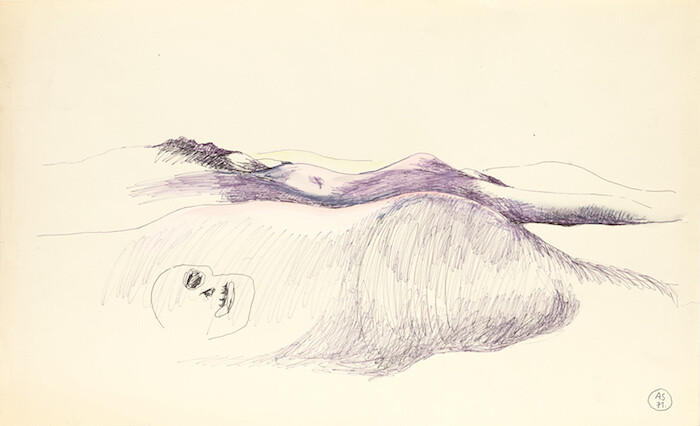

It is impossible not to associate these drawings of fragmented bodies and ghostly translucent figures with the atrocities that Szapocznikow witnessed while interned in Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, and Theresienstadt. Like most of her work, however, the “Human landscapes” are full of personal anguish as opposed to political aggression. Recalling the autobiographically sensual “body awareness paintings” of Maria Lassnig (another postwar artist who pushed the limits of figuration), Szapocznikow’s discombobulated figures describe an internal struggle. Having survived the Holocaust, the artist suffered from tuberculosis before eventually succumbing to cancer. Nowhere is the allusion to death more imminent and intimate than in a 1971 Human landscape featuring a purple-tinged female figure lying face-down in a landscape of gently rolling hills under which a skull lies buried. The contours of the woman’s outstretched arms, concave back, rounded buttocks, and slim legs echo the undulating ground beneath her. A hint of yellow at the horizon suggests a desert sun under which the lifeless body appears to be melting into the ground. Body and earth are in such close harmony here that they almost blur into one. With Szapocznikow’s ethereal interpretation of the figure-ground relationship we feel the artist coming to terms with her own mortality.

Pierre Restany cited in Allegra Pesenti, “Traces of passage: the drawings of Alina Szapocznikow,” in Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone 1955–1972, eds. Elena Filipovic and Joanna Mytkowska (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 96.